190295805319.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

Dissertation Summary of Three Recitals, with Works Derived from Folk Influences, Living American Composers and Works Containing a Theme and Variations

Dissertation Summary of Three Recitals, with Works Derived from Folk Influences, Living American Composers and Works Containing a Theme and Variations. by Heewon Uhm A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Halen, Chair Professor Anthony D. Elliott Professor Freda A. Herseth Professor Andrew W. Jennings Assisant Professor Youngju Ryu Heewon Uhm [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8334-7912 © Heewon Uhm 2019 DEDICATION To God For His endless love To my dearest teacher, David Halen For inviting me to the beautiful music world with full of inspiration To my parents and sister, Chang-Sub Uhm, Sunghee Chun, and Jungwon Uhm For trusting my musical journey ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF EXAMPLES iv ABSTRACT v RECITAL 1 1 Recital 1 Program 1 Recital 1 Program Notes 2 RECITAL 2 9 Recital 2 Program 9 Recital 2 Program Notes 10 RECITAL 3 18 Recital 3 Program 18 Recital 3 Program Notes 19 BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 iii LIST OF EXAMPLES EXAMPLE Ex-1 Semachi Rhythm 15 Ex-2 Gutgeori Rhythm 15 Ex-3 Honzanori-1, the transformed version of Semachi and Gutgeori rhythm 15 iv ABSTRACT In lieu of a written dissertation, three violin recitals were presented. Recital 1: Theme and Variations Monday, November 5, 2018, 8:00 PM, Stamps Auditorium, Walgreen Drama Center, University of Michigan. Assisted by Joonghun Cho, piano; Hsiu-Jung Hou, piano; Narae Joo, piano. Program: Olivier Messiaen, Thème et Variations; Johann Sebastian Bach, Ciaconna from Partita No. -

Download Booklet

572291bk Women EU 30/7/10 12:57 Page 4 Clare Howick Clare Howick has established herself as one of the leading violinists of her BRITISH WOMEN generation. She has a special interest in twentieth-century British violin repertoire which has resulted in a number of premières and recordings. Her début disc, Sonata Lirica and Other Works by Cyril Scott was Editor’s Choice in COMPOSERS Gramophone magazine. A second disc of Cyril Scott’s violin sonatas was subsequently recorded for Naxos (8.572290). She has performed most of the violin concerto repertoire with various orchestras including the Philharmonia Smyth • Maconchy • Poldowski Orchestra, has appeared at major festivals in Britain, including the Cheltenham International Festival, and has broadcast on BBC Radio 3. She combines solo and chamber performances with appearing as guest leader of many orchestras, Tate • Barns including the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Ulster Orchestra and the Orchestra of English National Opera. She Clare Howick, Violin • Sophia Rahman, Piano gratefully acknowledges the loan of a Stradivarius violin (1721) for this recording. Photograph: Guy Mayer Sophia Rahman Sophia Rahman has recorded over twenty chamber discs for companies including Naxos, ASV, Dutton/Epoch, Meridian, Linn Records, and Guild, among others. Her career encompasses solo, chamber and coaching activities. She acts as an official accompanist for the Lionel Tertis International Viola Competition, the Barbirolli International Oboe Competition and IMS/Prussia Cove. She has given master-classes in China at the Conservatory of Music in Xi An and the Xing Hai Conservatory of Music in Guangzhou, in Russia at the Modest Mussorgsky College in St Petersburg, in Sweden at Lilla Akadamien, Stockholm, and at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama. -

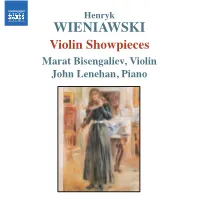

Wieniawski EU 2/26/08 2:01 PM Page 5

550744 bk Wieniawski EU 2/26/08 2:01 PM Page 5 Henryk Wienlawski (1835-1880) seinem Lehrer Massart gewidmet und eine glänzende nieder. Er schickte ein Telegramm an Isobels Mutter, in Kompositionen für Violine und Klavier Studie über den berühmten italienischen Tanz. dem er sie für das nächste Konzert einlud, das am Henryk Die Polonaisen, die Mazurka und der Kujawiak nächsten Tag stattfinden sollte. Auch Vater Hampton Henryk Wieniawski wurde am 10. Juni 1835 als Sohn befremdenden Streichquartette von Ludwig van zeigen Wieniawski als Meister im Umgang mit den kam, und nachdem er die Legende gehört und die des Militärarztes Tadeusz Wieniawski in Lublin Beethoven. polnischen Nationaltänzen, wohingegen die “Legende“ Reaktion seiner Tochter darauf beobachtet hatte, gab er WIENIAWSKI geboren. Seine Mutter Regina war die Tochter des Der Komponist Wieniawski hat naheliegenderweise in eine ganz andere Richtung weist. Sie ist das Zeugnis dem Paar seinen Segen. Henryk und Isobel heirateten angesehenen polnischen Pianisten Edward Wolff. wie viele seiner Kollegen sein eigenes Instrument in den seiner Liebe zu Isobel Hampton, die er zunächst nach und hatten fünf Kinder. Offenbar erkannten die Eltern früh die musikalische Mittelpunkt seiner Arbeit gestellt. Die beiden dem Willen ihres Vaters nicht heiraten sollte. Nachdem Begabung ihres Sohnes, und sie konnten es sich leisten, Violinkonzerte bilden einen Höhepunkt seines der Familienvorstand ihn in London hatte “abblitzen“ Keith Anderson Violin Showpieces ihn in die besten pädagogischen Hände zu geben: Sein Werkkatalogs; dazu kommen kammermusikalische lassen, zog sich Wieniawski zurück, um einige Stunden erster Lehrer war ein Schüler von Louis Spohr gewesen, Stücke für Violine und Klavier sowie Unterrichts- und Geige zu spielen - danach schrieb er die “Legende“ Deutsche Fassung: Cris Posslac der zweite unterrichtete unter anderem auch Joseph Anschauungsmaterial. -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No. -

Corey Cerovsek, Violin & Katja Cerovsek, Piano

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 2-20-1999 Concert: Corey Cerovsek, violin & Katja Cerovsek, piano Corey Cerovsek Katja Cerovsek Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1998-99 COREY CEROVSEK, violin KA TJA CEROVSEK, piano Polonaise No. 1 in D Major, op. 4 Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880) Sonata in C minor, op. 30, no. 2 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Allegro con brio Adagio cantabile Scherzo: Allegro Finale: Allegro-Presto Sonata No. 3 in G minor Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Allegro vivo Intermede-fantasque et Zeger Finale-tres anime INTERMISSION Sonata No. 1 in G Major, op. 78 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Vivace ma non troppo Adagio Allegro molto moderato Tzigane Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Saturday, February 20, 1999 Ford Hall Auditorium 8:15 p.m. DELOS RECORDS "/, Exclusive Management: ARTS MANAGEMENT GROUP, INC., 150 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 Public Relations/Publicity: M. L. FALCONE, Public Relations West 68th Street, Suite 1114 New York, NY 10023 PROGRAM NOTES Henryk Wieniawski ( 1835-1880). Polonaise No. 1 in D for Violin and Piano, op. 4 The son of the talented pianist Regina Wolff-Wieniawska, Henryk Wieniawski began his violin studies with Jan Hornziel and Stanislaw Serwaczynski (1791-1859), Joachim's first teacher. At the urging of her brother, the concert pianist Edouard Wolff, Henryk's mother took him to Paris where he was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire in 1843 and studied violin with Lambert-Joseph Massart (1811-92), Fritz Kreisler's teacher. -

Program Notes | Joshua Bell and Cristi

23 Season 2017-2018 Saturday, February 17, The Philadelphia Orchestra at 8:00 Cristian Măcelaru Conductor Joshua Bell Violin Beethoven Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72b Wieniawski Violin Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 22 I. Allegro moderato II. Romance: Andante non troppo III. Allegro con fuoco—Allegro moderato (à la Zingara) Intermission Dvořák Symphony No. 8 in G major, Op. 88 I. Allegro con brio II. Adagio—Poco più animato—Tempo I. Meno mosso III. Allegretto grazioso—Coda: Molto vivace IV. Allegro ma non troppo This program runs approximately 1 hour, 45 minutes. The February 17 concert is sponsored by Judith Broudy. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 25 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and impact through Research. is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues The Orchestra’s award- orchestras in the world, to discover new and winning Collaborative renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture Learning programs engage sound, desired for its its relationship with its over 50,000 students, keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home families, and community hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, members through programs audiences, and admired for and also with those who such as PlayINs, side-by- a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area sides, PopUP concerts, innovation on and off the performances at the Mann free Neighborhood concert stage. -

Week 3 DIGITAL

2021 The 25th Anniversary Season communicate • engage • inspire JULY 17 2021 - 2:00 PM streaming worldwide Click Play to Watch @HEIFETZINTERNATIONALMUSICINSTITUTE @HEIFETZMUSIC @HEIFETZMUSIC WWW.HEIFETZINSTITUTE.ORG Passacaglia Handel - Halvorsen Symphonie Espagnole in D minor, Op. 21 Edouard Lalo (1864–1935) I. Allegro non troppo (1823–1892) Da-Wei Chan, violin (12—Surrey, BC) Yumi Park, violin (14—Oakland Gardens, NY) Zachary Tsai, cello (13—San Gabriel, CA) Jingxuan Zhang, piano Variations On a Rococo Theme, Op. 33 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (abridged) (1840–1750) Cello Concerto in C major Joseph Haydn II. Adagio (1732–1809) Sungji Lindsey Lim, cello (14—Seoul, South Korea) Zachary Tsai, cello (13—San Gabriel, CA) Seongkyeong Yu, piano Julie Wong, piano Violin Concerto No. 22 in A minor Giovanni Battista Viotti I. Moderato (1755–1824) Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 27, No. 2 "Jacques Thibaud" Eugène Ysaÿe I. Obsession (1858–1931) Bill Jang, violin (12—New York, NY) Oliver Malkin, violin (12—Bethesda, MD) Jingxuan Zhang, piano Violin Concerto No. 22 in A minor Giovanni Battista Viotti Violin Concerto No. 22 in A minor Giovanni Battista Viotti II. Adagio (1755–1824) I. Moderato (1755–1824) Zoe Nguyen, violin (13—New York, NY) Jingxuan Zhang, piano Shira Braude, violin (11—Port Jefferson, NY) Eleanora Rotshteyn, piano Violin Concerto No. 23 in G major Giovanni Battista Viotti I. Allegro (1755–1824) Viola Concerto in D major, Op. 1 Carl Stamitz I. Allegro (1745–1801) William Fry, violin (10—Hong Kong) Jennifer Kang, viola (12—Mountain View, CA) Francis Saunders, piano Jingxuan Zhang, piano Scène de Ballet, Op. 100 Charles Auguste de Bériot Scène de Ballet, Op. -

Heifetz PEG Showcase I

HEIFETZ 2019 FESTIVAL OF CONCERTS – WEEK II FRIDAY, JULY 12 – HeifetzPEG Student Showcase I 12 PM – FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH Trio Sonata in C major, Op. 3 No. 8 Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713) North Fork Trio Airi Ito, violin Aerin Lee, violin Thomas Mesa, cello String Quartet No. 8 in F major, K. 168 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart III. Menuetto (1756–1791) IV. Allegro Cowpasture Quartet Jacqueline Rodenbeck, violin Bryan Hsu, violin Katharina Kang, viola Mila Wyrick, cello Viola Concerto in the Style of J. C. Bach, YC 98 Henri Casadesus I. Allegro molto ma maestoso (1879–1947) Kei Leigh Mese-Jones, cello Lynne Mackey, piano Cello Sonata No. 2 in G minor, Op. 5 No. 2 Ludwig van Beethoven II. Rondo. Allegro (1770–1827) Monica Dorn, cello Lynne Mackey, piano Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor Jean-Baptiste Accolay (1833–1900) Aerin Lee, violin David Ji, piano Introduction and Tarantella, Op. 43 Pablo de Sarasate (1844–1908) Airi Ito, violin Elena Lyalina, piano Five Pieces for Two Violins and Piano Dmitri Shostakovich Prelude (1906–1975) Gavotte Waltz South Fork Duo Yolanda Ni, violin Chloe Chung, violin Lynne Mackey, piano Six Duos from 44 Duos for Two Violins, Sz. 98 Béla Bartók (1881–1945) Potomac Duo Jessica Ma, violin Saya (Olivia) Jameson, violin Intermission Violin Partita No. 3 in E major, BWV 1006 Johann Sebastian Bach I. Preludio (1685–1750) Iris Danek, violin Scherzo tarantelle, Op. 16 Henryk Wieniawski (1835–1880) Bryan Hsu, violin David Ji, piano Havanaise, Op. 83 Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921) Jessica Ma, violin Elena Lyalina, piano Divertimento in D major Franz Joseph Haydn I. -

SPRING 2013 Allan Park – Northwest Chopin Council VOLUME XXIII/NUMBER 1 Scholarship Committee TABLE of CONTENTS Dr

The Semi-Annual Magazine of the Chopin Foundation of the USA CHOPIN FOUNDATION OF THE UNITED STATES, INC. Officers & Directors Krzysztof Penderecki Honorary Chairman Blanka A. Rosenstiel - Founder & President Olga Melin - Vice President Dr. William J. Hipp - Treasurer Rebecca Baez - Secretary Dr. Adam Aleksander - Artistic Advisor Jadwiga Viga Gewert - Executive Director Directors Agustin Anievas, , Roberta O. Chaplin, Douglas C. Evans, Rosa-Rita Gonzalez, Renate Ryan, Lorraine Sonnabend Regional Councils Mack McCray – San Francisco Chopin Council SPRING 2013 Allan Park – Northwest Chopin Council VOLUME XXIII/NUMBER 1 Scholarship Committee TABLE OF CONTENTS Dr. Adam Aleksander, Agustin Anievas, Dr. Hanna Cyba Message from the Founder and President ................................................................................... 2 Advisory Board Bonnie Barrett – Yamaha Artist Services Chopin Foundation Donors and Contributors ............................................................................... 3 Dr. Shelton Berg – University of Miami Frost School of Music Ron Losby – Steinway & Sons Message from the Executive Director .......................................................................................... 4 International Artistic Advisory Council Agustin Anievas, Martha Argerich, Emanuel Ax, Jeffrey N. Babcock, Highlights from our Recent Concerts ........................................................................................... 5 John Bayless, Luiz Fernando Benedini, John Corigliano, Ivan Davis, Christopher T. Dunworth, -

1 Spirituality and Romanticism Williams Chamber Players 02

Spirituality and Romanticism Williams Chamber Players 02 February 2018 Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) – Fratres (1977/1980) The Fratres Pärt premiered in 1977 consisted merely of the piano part of the present Fratres. Only three years later did Pärt add a violin, but today it can be difficult to imagine the piece without the violin. The opening violin solo invites comparison to the fragmented counterpoint of Bach’s Suites and Partitas for solo violin while the violin’s closing, stratospheric upper partials provide an ethereal complement to the satisfying return to the pitch center of A. The title, Latin for “brothers,” suggests the opening of the Epistle in the medieval Christian mass, a section in which the sub-deacon begins by saying “fratres” before proceeding to a reading. In the context of Pärt’s profoundly-felt Eastern Orthodox faith, we might understand the piece as a musical equivalent to a reading, inviting contemplation and perhaps claiming access to some type of spiritual truth. Certainly many listeners find themselves deeply affected by Pärt’s compositions. Musically, Fratres consists of cycles within cycles. Pärt punctuates this cyclicality with repeated forte chords low in the piano’s register, which divide the piece into nine iterations of the same rhythmic and melodic material in the piano, accompanied by changing violin figuration as in a set of variations. Within each iteration the piano states an initial pitch, departs from it by gradually ascending, leaps downward to a new note, and gradually returns to the initial pitch. After three increasingly lengthy departures, Pärt reverses the procedure and begins to descend rather than ascend for a parallel set of three departures.