Training Creative Violinists: Taking a Page from Baillot's L'art Du Violon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

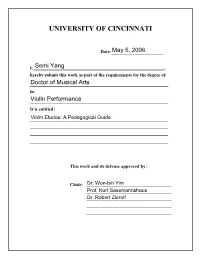

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ VIOLIN ETUDES: A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE A document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Semi Yang [email protected] B.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1995 M.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1999 Advisor: Dr. Won-bin Yim Reader: Prof. Kurt Sassmannshaus Reader: Dr. Robert Zierolf ABSTRACT Studying etudes is one of the most essential parts of learning a specific instrument. A violinist without a strong technical background meets many obstacles performing standard violin literature. This document provides detailed guidelines on how to practice selected etudes effectively from a pedagogical perspective, rather than a historical or analytical view. The criteria for selecting the individual etudes are for the goal of accomplishing certain technical aspects and how widely they are used in teaching; this is based partly on my experience and background. The body of the document is in three parts. The first consists of definitions, historical background, and introduces different of kinds of etudes. The second part describes etudes for strengthening technical aspects of violin playing with etudes by Rodolphe Kreutzer, Pierre Rode, and Jakob Dont. The third part explores concert etudes by Wieniawski and Paganini. -

Franco-Belgian Violin School: on the Rela- Tionship Between Violin Pedagogy and Compositional Practice Convegno Festival Paganiniano Di Carro 2012

5 il convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Convegno Società dei Concerti onlus 6 La Spezia Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini Lucca in collaborazione con Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de Musique Romantique Française Venezia Musicalword.it CAMeC Centro Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Piazza Cesare Battisti 1 Comitato scientifico: Andrea Barizza, La Spezia Alexandre Dratwicki, Venezia Lorenzo Frassà, Lucca Roberto Illiano, Lucca / La Spezia Fulvia Morabito, Lucca Renato Ricco, Salerno Massimiliano Sala, Pistoia Renata Suchowiejko, Cracovia Convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Programma Lunedì 9 LUGLIO 10.00-10.30: Registrazione e accoglienza 10.30-11.00: Apertura dei lavori • Roberto Illiano (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini / Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Francesco Masinelli (Presidente Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Massimiliano Sala (Presidente Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) • Étienne Jardin (Coordinatore scientifico Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) • Cinzia Aloisini (Presidente Istituzione Servizi Culturali, Comune della Spezia) • Paola Sisti (Assessore alla Cultura, Provincia della Spezia) 10.30-11.30 Session 1 Nicolò Paganini e la scuola franco-belga presiede: Roberto Illiano 7 • Renato Ricco (Salerno): Virtuosismo e rivoluzione: Alexandre Boucher • Rohan H. Stewart-MacDonald (Leominster, UK): Approaches to the Orchestra in Paganini’s Violin Concertos • Danilo Prefumo (Milano): L’infuenza dei Concerti di Viotti, Rode e Kreutzer sui Con- certi per violino e orchestra di Nicolò Paganini -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Violin Repertoire List

Violin Repertoire List In reverse order of difficulty (beginner books at top). Please send suggestions / additions to [email protected]. Version 1.1, updated 27 Aug 2015 List A: (Pieces in 1st position & basic notation) Fiddle Time Starters Fiddle Time Joggers Fiddle Time Runners Fiddle Time Sprinters The ABCs of Violin Musicland Violin Books Musicland Lollipop Man (Violin Duets) Abracadabra - Book 1 Suzuki Book 1 ABRSM Grade Book 1 VIolinSchool Editions: Popular Tunes in First Position ● Twinkle Twinkle Little Star ● London Bridge is Falling Down ● Frère Jacques ● When the Saints Go Marching In ● Happy Birthday to You ● What Shall We Do With the Drunken Sailor ● Ode to Joy ● Largo from The New World ● Long Long Ago ● Old MacDonald Had a Farm ● Pop! Goes the Weasel ● Row Row Row Your Boat ● Greensleeves ● The Irish Washerwoman ● Yankee Doodle Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 1 2 Step by Step Violin Play Violin Today String Builder Violin Book One (Samuel Applebaum) A Tune a Day I Can Read Music Easy Classical Violin Solos Violin for Dummies The Essential String Method (Sheila Nelson) Robert Pracht, Album of Easy Pieces, Op. 12 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 1 Waggon Wheels Superstudies (Mary Cohen) The Classical Experience Suzuki Book 2 Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 2 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 2 Alfred Moffat, Old Masters for Young Players D. Kabalevsky, Album Pieces for 1 and 2 Violins and Piano *************************************** List B: (Pieces in multiple positions and varieties of bow strokes) Level 1: Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor Johann Sebastian Bach: Air on the G string Bach Gavotte in D (Suzuki Book 3) Bach Gavotte in G minor (Suzuki Book 3) Béla Bartók: 44 Duos for two violins Karl Bohm www.ViolinSchool.org | [email protected] | +44 (0) 20 3051 0080 3 Perpetual Motion Frédéric Chopin Nocturne in C sharp minor (arranged) Charles Dancla 12 Easy Fantasies, Op.86 Antonín Dvořák Humoresque King Henry VIII Pastime with Good Company (ABRSM, Grade 3) Fritz Kreisler: Berceuse Romantique, Op. -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

Dissertation FINAL 5 22

ABSTRACT Title: BEETHOVEN’S VIOLINISTS: THE INFLUENCE OF CLEMENT, VIOTTI, AND THE FRENCH SCHOOL ON BEETHOVEN’S VIOLIN COMPOSITIONS Jamie M Chimchirian, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Dr. James Stern Department of Music Over the course of his career, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) admired and befriended many violin virtuosos. In addition to being renowned performers, many of these virtuosos were prolific composers in their own right. Through their own compositions, interpretive style and new technical contributions, they inspired some of Beethoven’s most beloved violin works. This dissertation places a selection of Beethoven’s violin compositions in historical and stylistic context through an examination of related compositions by Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755–1824), Pierre Rode (1774–1830) and Franz Clement (1780–1842). The works of these violin virtuosos have been presented along with those of Beethoven in a three-part recital series designed to reveal the compositional, technical and artistic influences of each virtuoso. Viotti’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in E major and Rode’s Violin Concerto No. 10 in B minor serve as examples from the French violin concerto genre, and demonstrate compositional and stylistic idioms that affected Beethoven’s own compositions. Through their official dedications, Beethoven’s last two violin sonatas, the Op. 47, or Kreutzer, in A major, dedicated to Rodolphe Kreutzer, and Op. 96 in G major, dedicated to Pierre Rode, show the composer’s reverence for these great artistic personalities. Beethoven originally dedicated his Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, to Franz Clement. This work displays striking similarities to Clement’s own Violin Concerto in D major, which suggests that the two men had a close working relationship and great respect for one another. -

![[STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , Von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2533/stendhal-joachim-rossini-von-maria-ottinguer-leipzig-1852-472533.webp)

[STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , Von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852

REVUE DES DEUX MONDES , 15th May 1854, pp. 731-757. Vie de Rossini , par M. BEYLE [STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852. SECONDE PÉRIODE ITALIENNE. — D’OTELLO A SEMIRAMIDE. IV. — CENERENTOLA ET CENDRILLON. — UN PAMPHLET DE WEBER. — LA GAZZA LADRA. — MOSÈ [MOSÈ IN EGITTO]. On sait que Rossini avait exigé cinq cents ducats pour prix de la partition d’Otello (1). Quel ne fut point l’étonnement du maestro lorsque le lendemain de la première représentation de son ouvrage il reçut du secrétaire de Barbaja [Barbaia] une lettre qui l’avisait qu’on venait de mettre à sa disposition le double de cette somme! Rossini courut aussitôt chez la Colbrand [Colbran], qui, pour première preuve de son amour, lui demanda ce jour-là de quitter Naples à l’instant même. — Barbaja [Barbaia] nous observe, ajouta-t-elle, et commence à s’apercevoir que vous m’êtes moins indifférent que je ne voudrais le lui faire croire ; les mauvaises langues chuchotent : il est donc grand temps de détourner les soupçons et de nous séparer. Rossini prit la chose en philosophe, et se rappelant à cette occasion que le directeur du théâtre Valle le tourmentait pour avoir un opéra, il partit pour Rome, où d’ailleurs il ne fit cette fois qu’une rapide apparition. Composer la Cenerentola fut pour lui l’affaire de dix-huit jours, et le public romain, qui d’abord avait montré de l’hésitation à l’endroit de la musique du Barbier [Il Barbiere di Siviglia ], goûta sans réserve, dès la première épreuve, cet opéra, d’une gaieté plus vivante, plus // 732 // ronde, plus communicative, mais aussi trop dépourvue de cet idéal que Cimarosa mêle à ses plus franches bouffonneries. -

Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," Edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai Clive Brown University of Leeds

Performance Practice Review Volume 21 | Number 1 Article 2 "Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai Clive Brown University of Leeds Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Performance Commons, and the Other Music Commons Brown, Clive (2016) ""Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 21: No. 1, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.201621.01.02 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol21/iss1/2 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book review: Illiano, R., M. Niccolai, eds. Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century. Turnhout: Brepols, 2014. ISBN: 9782503552477. Clive Brown Although the title of this book may suggest a comprehensive study of nineteenth- century conducting, it in fact contains a collection of eighteen essays by different au- thors, offering a series of highlights rather than a broad and connected picture. The collection arises from an international conference in La Spezia, Italy in 2011, one of a series of enterprising and stimulating annual conferences focusing on aspects of nineteenth-century music that has been supported by the Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini (Lucca), in this case in collaboration with the Società di Concerti della Spezia and the Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de musique romantique française (Venice). -

FONDO BAR CONSERVAZ 4 Parti Separate DOCUMENTO PER SOLA CONSULTAZIONE INTERNA

ELENCO DELLE NOTIZIE RISULTANTI DALLA RICERCA BIBLIOGRAFICA 1. er Quatuor pour 2 violons, alto et violoncelle : Op.10 / Claude Debussy . - [Parties]. - Paris : Durande & Fils, [s.d.]. - 4 parti (15 p.) ; 32 p. ((Dati bibliografici dalla prima pagina di musica. N.Inv.: 18658 MUSICA FONDO BAR CONSERVAZ 4 parti separate DOCUMENTO PER SOLA CONSULTAZIONE INTERNA 1. Vonosnegyes / Bela Bartok ; ellenoritze D. Dille. - [Szolamok]. - Budapest : Editio Musica, ©1956. - 4 parti (11 p.) ; 31 p. ((Dati bibliografici dalla copartina e dalle prima pagina di musica. N.Inv.: 18657 MUSICA FONDO BAR MC 0017 4 parti separate 1. Vonosnegyes : Op. 7 / Bartok Bela ; ellenoritze D. Dille. - [Partitura]. - Budapest : Editio Musica, ©1950. - 1 partiturina (39 p.) ; 20 cm. N.Inv.: 18656 MUSICA FONDO BAR MC 0016 1 partitura 10 Kunstler-Etuden fur Viola Op. 44 / von Johannes Palaschko . - Frankfurt am Main : Zimmermann, ©1965. - 29 p. ; 31 cm. N.Inv.: 18622 MUSICA FONDO BAR VA 0012 1 v. di musica a stampa DOCUMENTO PER SOLA CONSULTAZIONE INTERNA 12 studi op. 62 per viola / Johannes Palaschko . - Milano [etc.] : Ricordi, ©1923. - 21 p. ; 32 cm. ((Data di ripristino 1956. N.Inv.: 18624 MUSICA FONDO BAR VA 0013 1 v. di musica a stampa 12 studi per viola / Marco Anzoletti . - Milano [etc.] : Ricordi, ©1919. - 42 p. ; 32 cm. ((Dati bibliografici dal frontespizio e dalla prima pagina di musica. N.Inv.: 18614 MUSICA FONDO BAR VA 0014 1 v. di musica a stampa 19 Studi per violino / Kreutzer ; (Abbado). - Milano [etc.] : Ricordi, ©1955. - 20 p. ; 32 cm. N.Inv.: 18707 MUSICA FONDO BAR VL 0011 1 v. di musica a stampa 1er Grand Concerto pour piano et violon : Op. -

New 6-Page Template a 27/4/16 9:32 PM Page 1

573000bk Kummer:New 6-page template A 27/4/16 9:32 PM Page 1 Frédéric Kummer (1797–1879) und François Schubert (1808–1878) zu den bekanntesten Bühnenwerken des Opern- und führt im pianissimo wieder nach G-dur und zum Dreivier- Duos Concertants pour Violon et Violoncelle Ballettkomponisten Louis Joseph Ferdinand Hérold teltakt zurück – zunächst als ruhiges Moderato molto mit (1791–1833) und zu den beliebtesten Singspielen des 19. der Melodie im Violoncello, dann als abschließendes Friedrich August (alias Frédéric) Kummer wurde am 5. Unterricht bei seinem Vater und bei Antonio Rolla (1798- Jahrhunderts gehörte. Das Duo in der Tonart D-dur beginnt Allegro molto. August 1797 in Meiningen geboren. Sein Vater Friedrich 1837) wurde er in Paris von Charles Philippe Lafont (1781- mit einem Allegro, das neben einigen lieblichen Momenten Die Deux Duos de Concert pour Violon et Violoncelle August sen. (1770-1849) war zunächst Oboist in der 1839) ausgebildet, der seinerseits bei Rodolphe Kreutzer viel virtuoses Passagenwerk enthält. Von hier aus führt der op. 52 schließlich beginnen mit einem Souvenir de Fra Hofkapelle des Herzogs von Sachsen-Meiningen, und Pierre Rode studiert hatte. Da man ihn bisweilen mit Weg zu einem Andantino mit zwei Variationen, denen sich Diavolo, der wohl besten opéra-comique des Autorenteams übersiedelte aber mit seiner Familie bald nach der Geburt dem weitaus berühmteren Franz Schubert aus Wien ein Melancolico in Moll und im Dreivierteltakt anschließt. Daniel-François-Esprit Auber (1782–1871) und Eugène seines Sohnes nach Dresden und gab seinem Sprössling verwechselte, nahm er in Paris, wo er unter anderem mit Danach werden die ursprüngliche Tonart und der Scribe (1791–1861), dessen Namen wir üblicherweise im Frédéric den ersten Musikunterricht, bevor dieser von Justus Chopin Freundschaft schloss, den Namen »François« an. -

MUSIC in the EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Western Music in Context: a Norton History Walter Frisch Series Editor

MUSIC IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Western Music in Context: A Norton History Walter Frisch series editor Music in the Medieval West, by Margot Fassler Music in the Renaissance, by Richard Freedman Music in the Baroque, by Wendy Heller Music in the Eighteenth Century, by John Rice Music in the Nineteenth Century, by Walter Frisch Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries, by Joseph Auner MUSIC IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY John Rice n W. W. NORTON AND COMPANY NEW YORK ē LONDON W. W. Norton & Company has been independent since its founding in 1923, when William Warder Norton and Mary D. Herter Norton first published lectures delivered at the People’s Institute, the adult education division of New York City’s Cooper Union. The firm soon expanded its program beyond the Institute, publishing books by celebrated academics from America and abroad. By midcentury, the two major pillars of Norton’s publishing program— trade books and college texts—were firmly established. In the 1950s, the Norton family transferred control of the company to its employees, and today—with a staff of four hundred and a comparable number of trade, college, and professional titles published each year—W. W. Norton & Company stands as the largest and oldest publishing house owned wholly by its employees. Copyright © 2013 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Editor: Maribeth Payne Associate Editor: Justin Hoffman Assistant Editor: Ariella Foss Developmental Editor: Harry Haskell Manuscript Editor: JoAnn Simony Project Editor: Jack Borrebach Electronic Media Editor: Steve Hoge Marketing Manager, Music: Amy Parkin Production Manager: Ashley Horna Photo Editor: Stephanie Romeo Permissions Manager: Megan Jackson Text Design: Jillian Burr Composition: CM Preparé Manufacturing: Quad/Graphics—Fairfield, PA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rice, John A.