Breslow Dissertation Final Grad School Revision3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Evangelical Economic Rhetoric : : The Great Recession, the Free-Market and the Language of Personal Responsibility Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/504434dd Author Martin, Stephanie A. Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Evangelical Economic Rhetoric: The Great Recession, the Free-Market and the Language of Personal Responsibility A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Stephanie A. Martin Committee in Charge: Professor Robert B. Horwitz, Chair Professor John Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Valerie Hartouni Professor Isaac Martin 2013 Copyright Stephanie A. Martin, 2013 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Stephanie A. Martin is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2013 iii DEDICATION With enormous thanks to everyone who hung in there with me, through it all, skies blue or black. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page .............................................................................................................. iii Dedication ...................................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... -

311 Eons Free Mp3

311 eons free mp3 click here to download Download Eons mp3 songs in High Quality kbps format, Play Eons Music track mp3 download, Eons youtube to mp3 song. Similar Songs. - Sever · Play | Download · - Flowing · Play | Download · - beyond the grey sky · Play | Download · - Mindspin · Play | Download. Download MP3 Songs Free Online eons cleveland mp3 MP3 youtube downloader music free download - Search for your favorite music and download. Download MP3 Songs Free Online hero www.doorway.ru3 MP3 youtube downloader music free download - Search for your favorite music and download these in. Download MP3 Songs Free Online Full service covers at day www.doorway.ru3 MP3 youtube downloader music free download - Search for your favorite music. Buy Eons: Read 1 Digital Music Reviews - www.doorway.ru Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this song plus tens of millions Add to MP3 Cart. This is a list of tunes Eons ideal that individuals notify as well as display to you. All of us acquire a great deal of tunes Eons yet All of us solely show the. Download Seems Uncertain mp3 songs in High Quality kbps format, Play Seems Uncertain - Eons - Beautiful Disaster - Seems Uncertain. Watch the video, get the download or listen to – Eons for free. Eons appears on the album Soundsystem. Discover more music, gig and concert tickets. Eons live in Chicago HDNet Not an even field to be on feels like standing still for eons and eons. Bitrate: Kbps File Size: MB Song Duration: 3 min 23 sec Added to Favorite: K+. ▷ PLAY · DOWNLOAD. Eons mp3. -

Ecology of Alcohol and Other Drug Use: Helping Black High-Risk Youth

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 336 456 UD 028 200 AUTHOR Oyemade, Ura Jean, Ed.; Brandon-Monye, Deloris, Ed. TITLE Ecology of Alcohol and Other Drug Use: Helping Black High-Risk Youth. Proceedings of the Howard University School of Human Ecology Forum (Washington, D.C., October 26-27, 1987). OSAP Prevention Monograph-7. INSTITUTION Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (DHHS/PHS), Rockville, MD. Office for Substance Abuse Prevention. REPORT NO (ADM)-90-1672 PUB DATE 90 NOTE 245p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alcoha Abuse; Alcohol Education; *At Risk Persons; Black Culture; *Black Youth; Cocaine; Conference Proceedings; Cultural Influences; *Drug Abuse; Etiology; Family Environment; Incidence; Models; Prevention; Substance Abuse; *Urban Environment ABSTRACT Five plenary session presentations and summaries of 10 panel sessions held at a forum entitled "The Ecology of Substance Abuse: Toward Primary Prevention among High-Risk Youth" are provided in this document, which focuses on black youth at high risk for alcohol and drug problems. Experts describe a comprehensive ecological approach to addressing antecedent and concomitant factors related to alcohol and other drug use among black high-risk youth. Plenary session presentatiorn are: (1) "Implications of Alcohol and Other Drug Use for Black A. 'ica" (B. J. Prim); (2) "The Second Cocaine Epidemic" (D. F. MuEco); (3) "Prevention Models Targetedto Black Youth at High Risk for Alcohol and Other Drug Problems" (V. L. Smith); (4) "Primary Prevention from a Public Health :erspective:The Realities of the Urban Envircnment" (R. Tuckson); and (5) "An Ecological Model for Prevention of Drug Use" (C. -

DJ Music Catalog by Title

Artist Title Artist Title Artist Title Dev Feat. Nef The Pharaoh #1 Kellie Pickler 100 Proof [Radio Edit] Rick Ross Feat. Jay-Z And Dr. Dre 3 Kings Cobra Starship Feat. My Name is Kay #1Nite Andrea Burns 100 Stories [Josh Harris Vocal Club Edit Yo Gotti, Fabolous & DJ Khaled 3 Kings [Clean] Rev Theory #AlphaKing Five For Fighting 100 Years Josh Wilson 3 Minute Song [Album Version] Tank Feat. Chris Brown, Siya And Sa #BDay [Clean] Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love TK N' Cash 3 Times In A Row [Clean] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful Frenship 1000 Nights Elliott Yamin 3 Words Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful [Louie Vega EOL Remix - Clean Rachel Platten 1000 Ships [Single Version] Britney Spears 3 [Groove Police Radio Edit] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And A$AP #Beautiful [Remix - Clean] Prince 1000 X's & O's Queens Of The Stone Age 3's & 7's [LP] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And Jeezy #Beautiful [Remix - Edited] Godsmack 1000hp [Radio Edit] Emblem3 3,000 Miles Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful/#Hermosa [Spanglish Version]d Colton James 101 Proof [Granny With A Gold Tooth Radi Lonely Island Feat. Justin Timberla 3-Way (The Golden Rule) [Edited] Tucker #Country Colton James 101 Proof [The Full 101 Proof] Sho Baraka feat. Courtney Orlando 30 & Up, 1986 [Radio] Nate Harasim #HarmonyPark Wrabel 11 Blocks Vinyl Theatre 30 Seconds Neighbourhood Feat. French Montana #icanteven Dinosaur Pile-Up 11:11 Jay-Z 30 Something [Amended] Eric Nolan #OMW (On My Way) Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [KBCO Edit] Childish Gambino 3005 Chainsmokers #Selfie Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [Radio Edit] Future 31 Days [Xtra Clean] My Chemical Romance #SING It For Japan Michael Franti & Spearhead Feat. -

Zoey Schlemper, Even Though She Wasn’T Course in the Core Cur- the Monday After Gradu- Events

pages 6-7 Top five things to stub your toe on 5. Island counters 4. Couch Top Five Of everything 3. Door frame 2. Stairs 1. Chair leg THE CONCORDIAN ‘IVOL. 91,feel NO. 19 THURSDAY, like APRIL 16, 2015 – MOORHEAD, I MINN. am theTHECONCORDIAN.ORG token minority’ Students of color feel singled out on campus BY KALEY SIEVERT This fall, 2,381 students [email protected] enrolled and only 173 of those students are of color, Imagine going to a col- not including internation- lege where you are the mi- al students. nority. When sensitive soci- Scott Ellingson, Dean etal and cultural aspects of of Admissions, said that your race are brought up is about 7.5 percent of the in class, some people may student body. However, expect you to speak for the that percentage does not race you represent. You are include the few students afraid to speak up. who may not report their TOP PHOTO BY MADDIE MALAT This scenario is similar race when they enroll. El- Top: Kelsey Drayton, left, and Gabriel Walker stand in the Knutson Center Atrium as students walk by. to what Concordia juniors lingson said Admissions Above: Gabriel Walker is featured on Concordia’s website, a picture he thought would be of the entire table he was sit- Gabriel Walker and Kelsey gives students a choice to ting at in dining services. Drayton have felt while at- provide their race, but do ment to show how diverse was featured, Walker was think they used it for diver- and 5.7% of the two years tending Concordia College, not require them to. -

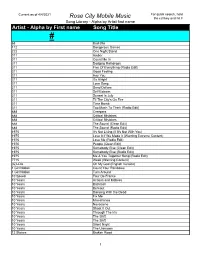

Alpha by First Name Song Title

Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title # 68 Bad Bite 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Amber 311 Count Me In 311 Dodging Raindrops 311 Five Of Everything (Radio Edit) 311 Good Feeling 311 Hey You 311 It's Alright 311 Love Song 311 Sand Dollars 311 Self Esteem 311 Sunset In July 311 Til The City's On Fire 311 Time Bomb 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 888 Creepers 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 The Sound (Clean Edit) 888 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 It's Not Living (If It's Not With You) 1975 Love It If We Made It (Warning Extreme Content) 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 1975 People (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) 1975 Me & You Together Song (Radio Edit) 7715 Week (Warning Content) (G)I-Dle Oh My God (English Version) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Burnout 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Novacaine 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years The Shift 10 Years The Shift 10 Years Silent Night 10 Years The Unknown 12 Stones Broken Road 1 Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • American Authors – Oh What a Life • Dierks

American Authors – Oh What A Life Dierks Bentley – Riser David Nail – I’m A Fire New Releases From Fontana North Inside!!! And more… UNI14-08 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: BECK – MORNING PHASE Bar Code: Cat. #: B001983802 Price Code: SP Order Due: Feb 13, 2014 Release Date: Feb 25, 2014 02537 64975 6 4 File: Alternative Genre Code: 2 Box Lot: 25 Key Tracks: Blue Moon Waking Light Super Short Sell Cycle Artist/Title: BECK – MORNING PHASE (Vinyl) – vinyl is one way sale Bar Code: Cat. #: B001983901 Price Code: Q 02537 64974 Order Due: Feb 13, 2014 Release Date: Feb 25, 2014 6 7 File: Alternative Genre Code: 2 Box Lot: Beck has signed to Capitol Records, and will release ‘Morning Phase’, the first album of all new material since 2008's universally acclaimed Modern Guilt on February 25th 2014. The new record has been described as a companion piece of sorts to Beck's 2002 classic Sea Change. Featuring many of the same musicians who played on that record, Morning Phase harkens back to the stunning harmonies, song craft and staggering emotional impact of Sea Change, while surging forward with infectious optimism. Morning Phase will be released on CD, vinyl, and digital download. BUY HERE’s WHY: -Beck has a >2x Platinum sales base in Canada, his first album of new material in 6 years. -Massive press looks being secured around release. -

Frederick Forsyth – the Devil's Alternative 4

Frederick Forsyth – The Devil’s Alternative BANTAM BOOKS NEW YORK • TORONTO • LONDON • SYDNEY • AUCKLAND 4 Frederick Forsyth – The Devil’s Alternative This edition contains the complete text of the original hardcover edition. NOT ONE WORD HAS BEEN OMITTED. THE DEVIL’S ALTERNATIVE A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with Viking Penguin. PUBLISHING HISTORY Viking edition published December 1979 Literary Guild edition March 1980 Serialized in PENTHOUSE; condensed by Reader’s Digest Condensed Books Bantam edition / July 1980 Bantam reissue / August 1995 All rights reserved. Copyright © 1979 by AHIARA International Corporation, S.A. Cover art copyright © 1995 by Bantam Books. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information address: Viking Penguin, 375 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. 10014. If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.” ISBN 0-553-26490-7 Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, a division of Bantam Double-day Dell Publishing Group, Inc. Its trademark, consisting of the words “Bantam Books” and the portrayal of a rooster, is Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam Books, 1540 Broadway, New York, New York 10036. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA RAD 24 23 5 Frederick Forsyth – The Devil’s Alternative FOR FREDERICK STUART, WHO DOES NOT KNOW YET 6 Frederick Forsyth – The Devil’s Alternative Contents PROLOGUE.................................................................................................................................................. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Education WILSON’S MANTRA: SENSEMAKING, LOOSE COUPLING, AND THE INTRAMURAL ECONOMIC ENGAGEMENT INTERFACE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS A Dissertation in Higher Education by James Kenneth Woodell © James Kenneth Woodell Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 ! ii The dissertation of James Kenneth Woodell was reviewed and approved* by the following: John J. Cheslock Associate Professor, Higher Education Program Dissertation Adviser, Chair of Committee Robert Hendrickson Professor, Higher Education Program Craig Weidemann Vice President for Outreach and Vice Provost for Online Education Göktuğ Morçöl Professor of Public Administration Dorothy Evensen Professor, Higher Education Program Program Coordinator, Higher Education Program *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ! iii Abstract Public research universities face increasing pressure from policy makers and the public to demonstrate economic relevance. As a response to this pressure, universities are adopting an “economically engaged” orientation, taking up and renewing commitments to technology-based economic development, workforce expansion, and cultivation of place through social, cultural, and community development. Research on university-engaged economic development has generally focused on external aspects of engagement, leaving internal organizational changes largely unexamined. When such research has been internally focused, it has been concerned with specific organizational units or functions within the research mission of the university, such as technology transfer operations or interdisciplinary research centers. In practice, engagement bridges internal and external aspects of the university. University economic engagement must employ aspects of the institution’s teaching and service missions as well as that of research, and it must include efforts across university units, departments, and functions. -

311 Archive Download Torrent 311 Archive Download Torrent

311 archive download torrent 311 archive download torrent. Certkingdom's preparation material includes the most excellent features, prepared by the same dedicated experts who have come together to offer an integrated solution. We provide the most excellent and simple method to pass your certification exams on the first attempt "GUARANTEED" Whether you want to improve your skills, expertise or career growth, with Certkingdom's training and certification resources help you achieve your goals. Our exams files feature hands-on tasks and real-world scenarios; in just a matter of days, you'll be more productive and embracing new technology standards. Our online resources and events enable you to focus on learning just what you want on your timeframe. You get access to every exams files and there continuously update our study materials; these exam updates are supplied free of charge to our valued customers. Get the best H41-311 exam Training; as you study from our exam-files "Best Materials Great Results" H41-311 Exam + Online / Offline and Android Testing Engine & 4500+ other exams included $70 - $50 (you save $20) Buy Now. Make The Best Choice Chose - Certkingdom Make yourself more valuable in today's competitive computer industry Certkingdom's preparation material includes the most excellent features, prepared by the same dedicated experts who have come together to offer an integrated solution. We provide the most excellent and simple method to pass your H41-311 exam on the first attempt "GUARANTEED". Unlimited Access Package will prepare you for your exam with guaranteed results, H41-311 Study Guide. Your exam will download as a single H41-311 PDF or complete H41-311 testing engine as well as over +4000 other technical exam PDF and exam engine downloads. -

Rose City Mobile Music

Current as of 1/5/2018 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title ~ Black rows are new additions # 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 311 Til The City's On Fire 0:00 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Creepers 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 0:00 The Sound (Clean Edit) 0:00 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) (Hed) P.E. Closer (Clean Radio Edit) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years Novacaine 12 Stones Broken Road 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975.. Chocolate 1975.. Girls (Warning Content) 1Love f Corey Hart Truth Will Set U Free 2 Chainz Crack (Warning Content) 2 Chainz I'm Different (Warning Content) 2 Chainz Riot (Clean Edit) 2 Chainz Spend It (Warning Content) 2 Chainz Used 2 (Warning Content) 2 Chainz Watch Out (Clean Edit) (Warning Extreme Content) 2 Chainz f Cap 1 Where U Been (Clean Edit) (Warning Extreme Content) 2 Chainz f Drake No Lie (Clean Edit) (Warning Content) 2 Chainz f Drake Big Amount (Clean Edit) (Warning Content) 2 Chainz -

Tales of the Five Towns by Arnold Bennett</H1>

Tales of the Five Towns by Arnold Bennett Tales of the Five Towns by Arnold Bennett Produced by Jonathan Ingram and PG Distributed Proofreaders TALES OF THE FIVE TOWNS By ARNOLD BENNETT * * * * * First published January 1905 * * * * * page 1 / 246 TO MARCEL SCHWOB MY LITERARY GODFATHER IN FRANCE * * * * * CONTENTS PART I AT HOME HIS WORSHIP THE GOOSEDRIVER THE ELIXIR OF YOUTH MARY WITH THE HIGH HAND THE DOG A FEUD PHANTOM TIDDY-FOL-LOL THE IDIOT PART II page 2 / 246 ABROAD THE HUNGARIAN RHAPSODY THE SISTERS QITA NOCTURNE AT THE MAJESTIC CLARICE OF THE AUTUMN CONCERTS A LETTER HOME * * * * * PART I AT HOME * * * * * HIS WORSHIP THE GOOSEDRIVER I It was an amiable but deceitful afternoon in the third week of December. Snow fell heavily in the windows of confectioners' shops, and Father page 3 / 246 Christmas smiled in Keats's Bazaar the fawning smile of a myth who knows himself to be exploded; but beyond these and similar efforts to remedy the forgetfulness of a careless climate, there was no sign anywhere in the Five Towns, and especially in Bursley, of the immediate approach of the season of peace, goodwill, and gluttony on earth. At the Tiger, next door to Keats's in the market-place, Mr. Josiah Topham Curtenty had put down his glass (the port was kept specially for him), and told his boon companion, Mr. Gordon, that he must be going. These two men had one powerful sentiment in common: they loved the same woman. Mr. Curtenty, aged twenty-six in heart, thirty-six in mind, and forty-six in looks, was fifty-six only in years.