Real Diaries of Young People Who Lived During the Holocaust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publicity of the Intimate Text (The Blog Studying and Publication)

Publicity of the intimate text (the blog studying and publication) One of the important problems of a modern society – communications. At all readiness of this question both humanitarian, and engineering science, process of transfer and information reception remains in the centre of attention of researchers. The dialogue phenomenon in a network becomes the significant factor of such attention. The possibility of the user choice, freedom of expression of feelings and requirements, communications and information interchange freedom – define principles of the Open Internet not only specificity of communications in networks, but also genre and stylistics possibilities of the texts providing dialogue. Today Internet users apply various possibilities of the network, one of the most demanded – a blog. The Internet as an open space of dialogue allows the texts created and functioning in a network, to pass and in fiction sphere. We can observe similar processes concerning a genre of a diary and its genre versions: Network diary (Internet diary) – a blog – and an art (literary) diary. The diary as an auto-documentation genre at the present stage of its development gets from especially intimate conditions on Internet space. The blog phenomenon reflects as potential of publicity of the text of the records, peculiar to a genre, and feature of a modern cultural situation. Popularity of Internet diaries defines interest to them and readers of a fiction with what cases of the publication of blogs, significant both in substantial, and in the art relation are connected. So, publications of the Russian bloggers are known: for example, the artist Peter Lovygin (lovigin.livejournal.com) [3], etc. -

What Do Students Know and Understand About the Holocaust? Evidence from English Secondary Schools

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster, Alice Pettigrew, Andy Pearce, Rebecca Hale Centre for Holocaust Education Centre Adrian Burgess, Paul Salmons, Ruth-Anne Lenga Centre for Holocaust Education What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Cover image: Photo by Olivia Hemingway, 2014 What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster Alice Pettigrew Andy Pearce Rebecca Hale Adrian Burgess Paul Salmons Ruth-Anne Lenga ISBN: 978-0-9933711-0-3 [email protected] British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record is available from the British Library All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permissions of the publisher. iii Contents About the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education iv Acknowledgements and authorship iv Glossary v Foreword by Sir Peter Bazalgette vi Foreword by Professor Yehuda Bauer viii Executive summary 1 Part I Introductions 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Methodology 23 Part II Conceptions and encounters 35 3. Collective conceptions of the Holocaust 37 4. Encountering representations of the Holocaust in classrooms and beyond 71 Part III Historical knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust 99 Preface 101 5. Who were the victims? 105 6. -

„Grossaktion” (22 July 1942 – 21 September 1942)

„Grossaktion” (22 July 1942 – 21 September 1942) The Nazi authorities started to carry out the plans for annihilating European Jews from the second half of 1941, when German troops marched into the USSR. If we deem the activities of the Einsatzgruppen as phase one of the extermination and the ones commenced nine months later (“Operation Reinhardt”) as its escalation, the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto – conducted between 22 July and 21 September 1942 under the codename “Grossaktion” – should be regarded as a supplement of the genocide plan. All of them were parts of the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question”. Announcements. In the afternoon of July 20th, cars with SS officers start appearing in the Ghetto. Guard posts at the exits leading to the “Aryan District” have been reinforced. A security cordon was established along the walls, comprised of uniformed Lithuanian, Latvian, and Ukrainian troops. Stefan Ernest, working at the Ghetto Employment Office, noted at that time, his feeling of impending cataclysm to erupt in Warsaw, the largest conglomeration of Jews in German-occupied Europe: “It was clear that some invisible hand was orchestrating a spectacle that is yet to begin. The current goings on are just a tuning of instruments getting ready to play some dreadful symphony. Some sort of »La danse macabre«” . On the same day, when many Judenrat representatives were arrested in the afternoon and transported to the Pawiak prison, Ernest wrote: “The Game has begun”. The city was gripped in fear. Everything indicated that the future of the Jews was already settled. The screenplay, methods and manner of its execution remained unknown. -

Study Guide for Band of Brothers – Episode 9: Why We Fight

Study Guide for Band of Brothers – Episode 9: Why We Fight INTRO: Band of Brothers is a ten-part video series dramatizing the history of one company of American paratroopers in World War Two—E Company, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne, known as “Easy Company.” Although the company’s first experience in real combat did not come until June 1944 ( D-Day), this exemplary group fought in some of the war’s most harrowing battles. Band of Brothers depicts not only the heroism of their exploits but also the extraordinary bond among men formed in the crucible of war. In the ninth episode, Easy Company finally enters Germany in April 1945, finding very little resistance as they proceed. There they are impressed by the industriousness of the defeated locals and gain respect for their humanity. But the G.I.s are then confronted with the horror of an abandoned Nazi concentration camp in the woods, which the locals claim not to have known anything about. Here the story of Easy Company is connected with the broader narrative of the war—the ideology of the Third Reich and Hitler’s plan to exterminate the Jews. CURRICULUM LINKS: Band of Brothers can be used in history classes. NOTE TO EDUCATORS: Band of Brothers is appropriate as a supplement to units on World War Two, not as a substitute for material providing a more general explanation of the war’s causes, effects, and greater historical significance. As with war itself, it contains graphic violence and language; it is not for the squeamish. Mature senior high school students, however, will find in it a powerful evocation of the challenges of war and the experience of U.S. -

The Disturbing Victims of Chuck Palahniuk

The Disturbing Victims of Chuck Palahniuk Anders Westlie Master thesis at ILOS UNIVERSITETET I OSLO 16.11.2012 II The Disturbing Victims of Chuck Palahniuk III © Anders Westlie 2012 The Disturbing Victims of Chuck Palahniuk Anders Westlie http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: CopyCat Express, Oslo IV Abstract The writings of Chuck Palahniuk contain a large variety of strange and interesting characters. Many of them are victims of the choices they or others made, which is how their lives become interesting. I aim to see if there is any basis in reality for some of the situations and fears that happen. I also mean that Palahniuk thinks people are afraid of the wrong things, and afraid of too many things in general, and will approach this theory in my discussion. V VI Introduction This thesis has been through an abundance of versions and changed shape and content very many times over the years; from being all psychoanalysis to pure close reading, and ended with a study of victims, fears and reactions. In the end, the amount of close reading that has gone into it has bypassed the use of theory. This is mostly a reaction to past criticism to my over-use of critics, and focusing on that rather than the texts at hand. I find my time disposition in the production process of this paper to be shame, but life will sometimes get in the way of good intentions. As such, I hope that you, dear reader, find my efforts not in vain and take some interest in what my efforts have produced. -

CHAI News Fall 2018

CENTER FOR HOLOCAUST October 2018 AWARENESS AND INFORMATION (CHAI) CHAI update Tishri-Cheshvan 5779 80 YEARS AFTER KRISTALLNACHT: Remember and Be the Light Thursday, November 8, 2018 • 7—8 pm Fabric of Survival for Educators Temple B’rith Kodesh • 2131 Elmwood Ave Teacher Professional Development Program Kristallnacht, also known as the (Art, ELA, SS) Night of Broken Glass, took place Wednesday, October 3 on November 9-10, 1938. This 4:30—7:00 pm massive pogrom was planned Memorial Art Gallery and carried out 80 years ago to terrorize Jews and destroy Jewish institutions (synagogues, schools, etc.) throughout Germa- ny and Austria. Firefighters were in place at every site but their duty was not to extinguish the fire. They were there only to keep the fire from spreading to adjacent proper- ties not owned by Jews. A depiction of Passover by Esther Historically, Kristallnacht is considered to be the harbinger of the Holocaust. It Nisenthal Krinitz foreshadowed the Nazis’ diabolical plan to exterminate the Jews, a plan that Esther Nisenthal Krinitz, Holocaust succeeded in the loss of six million. survivor, uses beautiful and haunt- ing images to record her story when, If the response to Kristallnacht had been different in 1938, could the Holocaust at age 15, the war came to her Pol- have been averted? Eighty years after Kristallnacht, what are the lessons we ish village. She recounts every detail should take away in the context of today’s world? through a series of exquisite fabric collages using the techniques of em- This 80 year commemoration will be a response to these questions in the form broidery, fabric appliqué and stitched of testimony from local Holocaust survivors who lived through Kristallnacht, narrative captioning, exhibited at the as well as their direct descendents. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Y'all Call It Technical and Professional Communication, We Call It

Y’ALL CALL IT TECHNICAL AND PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION, WE CALL IT #FORTHECULTURE: THE USE OF AMPLIFICATION RHETORICS IN BLACK COMMUNITIES AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR TECHNICAL AND PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION STUDIES by Temptaous T. Mckoy July 2019 Director of Dissertation: Michelle F. Eble Major Department: Department of English This project seeks to define and identify the use of Amplification Rhetorics (AR) in the social movement organization TRAP Karaoke and at three Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). In highlighting the AR practices in Black communities. This project will provide insight into what these practices and spaces have to offer to the field of Technical and Professional Communication (TPC). AR is a theoretical framework that details the discursive and communicative practices, both written/textual and embodied/performative performed/used by individuals that self-identify as Black and centers the lived experiences and epistemologies of Black people and other historically marginalized groups. AR are #ForTheCulture practices that provoke change within the academy, regardless the field, however for this project I focus on the field of TPC. The phrase “For the Culture,” is used to describe or allude to an action that can benefit those individually or within a community much like TPC artifacts. This project identifies rhetorical practices located in Black spaces and communities that can be identified as TPC through the reclamation of agency, the sharing of narratives, and the inclusion of Black epistemologies. It illustrates just what it means to pass the mic and remind folks that we not ‘bout to act like there aren’t people of color at the TPC table. -

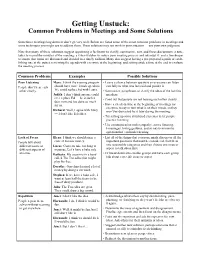

Getting Unstuck: Common Problems in Meetings and Some Solutions

Getting Unstuck: Common Problems in Meetings and Some Solutions Sometimes meetings bog down or don’t go very well. Below are listed some of the most common problems in meetings and some techniques you might use to address them. These solutions may not work in your situation — use your own judgment. Note that many of these solutions suggest appointing a facilitator to clarify, summarize, sort, and focus discussions; a note- taker to record the minutes of the meeting; a vibes-watcher to notice poor meeting process and interrupt it; and a timekeeper to ensure that items are discussed and decided in a timely fashion. Many also suggest having a pre-prepared agenda or estab- lishing one at the outset, reviewing the agenda with everyone at the beginning, and setting aside a time at the end to evaluate the meeting process. Common Problems Examples Possible Solutions Poor Listening Mary: I think the evening program • Leave a silence between speakers so everyone can listen People don’t hear each should have more female speakers. carefully to what was last said and ponder it. other clearly. We could replace Ed with Laura. • Summarize, paraphrase, or clarify the ideas of the last few Judith: I don’t think anyone could speakers. ever replace Ed — he is such a • Point out that people are not hearing each other clearly. dear man and has done so much for us. • Have a check-in time at the beginning of meetings for everyone to say in turn what is on their minds, so they Richard: Well, I agree with Mary won’t be distracted by it later during the meeting. -

The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann (Pdf)

6/28/2020 The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann » Mosaic THE TRUTH OF THE CAPTURE OF ADOLF EICHMANN https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/history-ideas/2020/06/the-truth-of-the-capture-of-adolf-eichmann/ Sixty years ago, the infamous Nazi official was abducted in Argentina and brought to Israel. What really happened, what did Hollywood make up, and why? June 1, 2020 | Martin Kramer About the author: Martin Kramer teaches Middle Eastern history and served as founding president at Shalem College in Jerusalem, and is the Koret distinguished fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Listen to this essay: Adolf Eichmann’s Argentinian ID, under the alias Ricardo Klement, found on him the night of his abduction. Yad Vashem. THE MOSAIC MONTHLY ESSAY • EPISODE 2 June: The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann 1x 00:00|60:58 Sixty years ago last month, on the evening of May 23, 1960, the Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion made a brief but dramatic announcement to a hastily-summoned session of the Knesset in Jerusalem: A short time ago, Israeli security services found one of the greatest of the Nazi war criminals, Adolf Eichmann, who was responsible, together with the Nazi leaders, for what they called “the final solution” of the Jewish question, that is, the extermination of six million of the Jews of Europe. Eichmann is already under arrest in Israel and will shortly be placed on trial in Israel under the terms of the law for the trial of Nazis and their collaborators. In the cabinet meeting immediately preceding this announcement, Ben-Gurion’s ministers had expressed their astonishment and curiosity. -

Fresh Dressed

PRESENTS FRESH DRESSED A CNN FILMS PRODUCTION WORLD PREMIERE – DOCUMENTARY PREMIERE Running Time: 82 Minutes Sales Contact: Dogwoof Ana Vicente – Head of Theatrical Sales Tel: 02072536244 [email protected] 1 SYNOPSIS With funky, fat-laced Adidas, Kangol hats, and Cazal shades, a totally original look was born— Fresh—and it came from the black and brown side of town where another cultural force was revving up in the streets to take the world by storm. Hip-hop, and its aspirational relationship to fashion, would become such a force on the market that Tommy Hilfiger, in an effort to associate their brand with the cultural swell, would drive through the streets and hand out free clothing to kids on the corner. Fresh Dressed is a fascinating, fun-to-watch chronicle of hip-hop, urban fashion, and the hustle that brought oversized pants and graffiti-drenched jackets from Orchard Street to high fashion's catwalks and Middle America shopping malls. Reaching deep to Southern plantation culture, the Black church, and Little Richard, director Sacha Jenkins' music-drenched history draws from a rich mix of archival materials and in-depth interviews with rappers, designers, and other industry insiders, such as Pharrell Williams, Damon Dash, Karl Kani, Kanye West, Nasir Jones, and André Leon Talley. The result is a passionate telling of how the reach for freedom of expression and a better life by a culture that refused to be squashed, would, through sheer originality and swagger, take over the mainstream. 2 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS SACHA JENKINS – Director Sacha Jenkins, a native New Yorker, published his first magazine—Graphic Scenes & X-Plicit Language (a ‘zine about the graffiti subculture)—at age 17. -

Holocaust Glossary

Holocaust Glossary A ● Allies: 26 nations led by Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union that opposed Germany, Italy, and Japan (known as the Axis powers) in World War II. ● Antisemitism: Hostility toward or hatred of Jews as a religious or ethnic group, often accompanied by social, economic, or political discrimination. (USHMM) ● Appellplatz: German word for the roll call square where prisoners were forced to assemble. (USHMM) ● Arbeit Macht Frei: “Work makes you free” is emblazoned on the gates at Auschwitz and was intended to deceive prisoners about the camp’s function (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Aryan: Term used in Nazi Germany to refer to non-Jewish and non-Gypsy Caucasians. Northern Europeans with especially “Nordic” features such as blonde hair and blue eyes were considered by so-called race scientists to be the most superior of Aryans, members of a “master race.” (USHMM) ● Auschwitz: The largest Nazi concentration camp/death camp complex, located 37 miles west of Krakow, Poland. The Auschwitz main camp (Auschwitz I) was established in 1940. In 1942, a killing center was established at Auschwitz-Birkenau (Auschwitz II). In 1941, Auschwitz-Monowitz (Auschwitz III) was established as a forced-labor camp. More than 100 subcamps and labor detachments were administratively connected to Auschwitz III. (USHMM) Pictured right: Auschwitz I. B ● Babi Yar: A ravine near Kiev where almost 34,000 Jews were killed by German soldiers in two days in September 1941 (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Barrack: The building in which camp prisoners lived. The material, size, and conditions of the structures varied from camp to camp.