Y'all Call It Technical and Professional Communication, We Call It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Rhetoric: Toward an Integrated Theory

TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION QUARTERLY, 14(3), 319–325 Copyright © 2005, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Digital Rhetoric: Toward an Integrated Theory James P. Zappen Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute This article surveys the literature on digital rhetoric, which encompasses a wide range of issues, including novel strategies of self-expression and collaboration, the characteristics, affordances, and constraints of the new digital media, and the forma- tion of identities and communities in digital spaces. It notes the current disparate na- ture of the field and calls for an integrated theory of digital rhetoric that charts new di- rections for rhetorical studies in general and the rhetoric of science and technology in particular. Theconceptofadigitalrhetoricisatonceexcitingandtroublesome.Itisexcitingbe- causeitholdspromiseofopeningnewvistasofopportunityforrhetoricalstudiesand troublesome because it reveals the difficulties and the challenges of adapting a rhe- torical tradition more than 2,000 years old to the conditions and constraints of the new digital media. Explorations of this concept show how traditional rhetorical strategies function in digital spaces and suggest how these strategies are being reconceived and reconfiguredDo within Not these Copy spaces (Fogg; Gurak, Persuasion; Warnick; Welch). Studies of the new digital media explore their basic characteris- tics, affordances, and constraints (Fagerjord; Gurak, Cyberliteracy; Manovich), their opportunities for creating individual identities (Johnson-Eilola; Miller; Turkle), and their potential for building social communities (Arnold, Gibbs, and Wright; Blanchard; Matei and Ball-Rokeach; Quan-Haase and Wellman). Collec- tively, these studies suggest how traditional rhetoric might be extended and trans- formed into a comprehensive theory of digital rhetoric and how such a theory might contribute to the larger body of rhetorical theory and criticism and the rhetoric of sci- ence and technology in particular. -

Information Design and Uncertain Environments: Cognitive and Ecological Considerations in Technical Communication

Information Design and Uncertain Environments: Cognitive and Ecological Considerations in Technical Communication By Christopher Cocchiarella Abstract: While technical communication has roots in the rhetorical tradition, it also has been influenced by positivism and computationalism, which, unlike rhetoric, treat facts separately from values and isolate information from social contexts by organizing data into digital ‘bits.’ Technical communicators uncritical of such assumptions may unintentionally design information inappropriate for their audiences’ social values or their users’ situation. To illustrate, this paper analyzes a case study of technical communication graduate students who worked on an information design project that ultimately failed. In an information design course, technical communication graduate students tried to design a short messaging service (SMS) system for clients in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They collaborated on this project with a non-governmental organization, which asked them to devise an SMS system that could deliver pricing information to Congolese miners and farmers who own cell phones with text messaging capacities. As the students tried to design this SMS system, however, they realized that most technological aspects of the design were relatively trivial compared to its trustworthiness and context of use—e.g., they questioned where the pricing information would come from, how it could be trusted, and if it could be communicated in ways that would incentivize negotiation and cooperation among users. Concerns about trust value and usability context became greater issues than pricing information and SMS content, halting the implementation of the original SMS design. As a case study, the SMS project demonstrates the need for cognitive and ecological considerations in technical communication. -

Bullets High Five

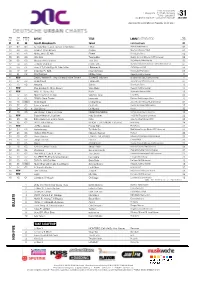

DUC REDAKTION Hofweg 61a · D-22085 Hamburg T 040 - 369 059 0 WEEK 31 [email protected] · www.trendcharts.de 29.07.2021 Approved for publication on Tuesday, 03.08.2021 THIS LAST WEEKS IN PEAK WEEK WEEK CHARTS ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 01 06 Tyga Ft. Moneybagg Yo Splash Last Kings/Empire 01 02 02 07 Ty Dolla $ign x Jack Harlow x 24kGoldn I Won Atlantic/WMI/Warner 02 03 04 05 Wale Ft. Chris Brown Angles Maybach/Warner/WMI 03 04 03 08 Nicky Jam x El Alfa Pikete Sony Latin/Sony 02 05 05 09 City Girls Twerkulator Quality Control/Motown/UMI/Universal 02 06 06 06 Meghan Thee Stallion Thot Shit 300/Atlantic/WMI/Warner 03 07 14 03 J Balvin x Skrillex In Da Getto Sueños Globales/Universal Latin/UMI/Universal 07 08 09 04 dvsn & Ty Dolla $ign Ft. Mac Miller I Believed It OVO/Warner/WMI 08 09 17 07 Doja Cat Ft. SZA Kiss Me More Kemosabe/RCA/Sony 08 10 21 02 Post Malone Motley Crew Republic/UMI/Universal 10 11 NEW Daddy Yankee Ft. Jhay Cortez & Myke Towers Súbele El Volumen El Cartel/Republic/UMI/Universal 11 12 07 03 Shirin David Lieben Wir Juicy Money/VEC/Universal 01 13 13 02 Maluma Sobrio Sony Latin/Sony 13 14 NEW Pop Smoke Ft. Chris Brown Woo Baby Republic/UMI/Universal 14 15 NEW MIST Ft. Burna Boy Rollin Sickmade/Warner/WMI 15 16 12 03 Brent Faiyaz Ft. Drake Wasting Time Lost Kids 09 17 11 04 RIN Ft. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

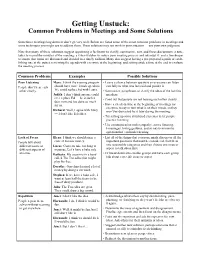

Getting Unstuck: Common Problems in Meetings and Some Solutions

Getting Unstuck: Common Problems in Meetings and Some Solutions Sometimes meetings bog down or don’t go very well. Below are listed some of the most common problems in meetings and some techniques you might use to address them. These solutions may not work in your situation — use your own judgment. Note that many of these solutions suggest appointing a facilitator to clarify, summarize, sort, and focus discussions; a note- taker to record the minutes of the meeting; a vibes-watcher to notice poor meeting process and interrupt it; and a timekeeper to ensure that items are discussed and decided in a timely fashion. Many also suggest having a pre-prepared agenda or estab- lishing one at the outset, reviewing the agenda with everyone at the beginning, and setting aside a time at the end to evaluate the meeting process. Common Problems Examples Possible Solutions Poor Listening Mary: I think the evening program • Leave a silence between speakers so everyone can listen People don’t hear each should have more female speakers. carefully to what was last said and ponder it. other clearly. We could replace Ed with Laura. • Summarize, paraphrase, or clarify the ideas of the last few Judith: I don’t think anyone could speakers. ever replace Ed — he is such a • Point out that people are not hearing each other clearly. dear man and has done so much for us. • Have a check-in time at the beginning of meetings for everyone to say in turn what is on their minds, so they Richard: Well, I agree with Mary won’t be distracted by it later during the meeting. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

Communication Models and the CMAPP Analysis

CHAPTER 2 Communication Models and the CMAPP Analysis f you want to find out the effect on Vancouver of a two-foot rise in sea level, you wouldn’t try to melt the polar ice cap and then visit ICanada. You’d try to find a computer model that would predict the likely consequences. Similarly, when we study technical communication, we use a model. Transactional Communication Models Various communication models have been developed over the years. Figure 2.1 on the next page shows a simple transactional model, so called to reflect the two-way nature of communication. The model, which in principle works for all types of oral and written communication, has the following characteristics: 1. The originator of the communication (the sender) conveys (trans- mits) it to someone else (the receiver). 2. The transmission vehicle might be face-to-face speech, correspon- dence, telephone, fax, or e-mail. 3. The receiver’s reaction (e.g., body language, verbal or written response)—the feedback—can have an effect on the sender, who may then modify any further communication accordingly. 16 Chapter 2 FIGURE 2.1 A Simple Transactional Model As an example, think of a face-to-face conversation with a friend. As sender, you mention what you think is a funny comment made by another student named Maria. (Note that the basic transmission vehicle here is the sound waves that carry your voice.) As you refer to her, you see your friend’s (the receiver’s) face begin to cloud over, and you remember that your friend and Maria strongly dislike each other. -

Intercom-January-2016.Pdf

January 2016 THE MAGAZINE OF THE SOCIETY FOR TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION learn by yourself learn with others get certified CERTIFICATION AND STC’S CERTIFIED PROFESSIONAL TECHNICAL COMMUNICATOR: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW 6 CERTIFIED PROFESSIONAL TECHNICAL COMMUNICATOR: THE EXAM AND ITS take the exam online NINE AREAS OF COMPETENCY 10 PATIENT EXPERIENCE DESIGN 12 BUILDING CONTENT CAPACITIES WITHIN NON-PROFITS 16 A TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION USER’S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS 20 LEARN WHY THOUSANDS OF COMPANIES ARE MAKING THE SWITCH TO MADCAP SOFTWARE MadCap Flare’s single-sourcing capabilities help us streamline our processes to rapidly deliver the information our customers need for any new product releases.” Pat Holmes-Clark, Team Leader and Specialist Technical Writer | McKesson Health Solutions Largest Healthcare Services Company in the United States Switches to MadCap Flare for Agile Delivery of Online Help and Documentation We were working with multiple Microsoft® Word™ or FrameMaker® files, and it became confusing to try and manage them all. It was extremely time-intensive and inefficient to update these files for each product release.” Lesley Brown, Associate Vice President of Documentation and Training Development | McKesson Health Solutions STREAMLINE YOUR CONTENT DELIVERY WITH THE MADPAK PROFESSIONAL SUITE Everything You Need to Create, Manage and Publish Professional Content MadCap Flare: Industry-leading Authoring, Publishing and Content Management MadCap Controbutor: Contribution and Review for Anyone in Your Organization MadCap Analyzer: Powerful Project Analysis and Reporting MadCap Mimic: Create Fully Interactive Demos, Video Tutorials and Software Simulations MadCap Capture: Screen Capture and Image Editing Made Easy Copyright © 2016, MadCap Software, Inc., and its licensor’s. All rights reserved. -

Piercy 2020 Mobilemedia&Com

EXPECTATIONS OF TECHNOLOGY USE DURING MEETINGS 1 Expectations of technology use during meetings: An experimental test of manager policy, device-use, and task-acknowledgement Cameron W. Piercy1 Greta R. Underhill1 Author information: 1Department of Communication Studies, University of Kansas, 1440 Jayhawk Blvd., Room 102, Lawrence, KS 66044, +1-785-864-5989 Corresponding author, Cameron W. Piercy, Ph.D., [email protected] Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank Drs. Norah Dunbar, Joann Keyton, and the two anonymous reviewers for valuable feedback on this manuscript. Thank you to Drs. Michael Ault and Kathryn Lookadoo for assisting with the manipulation vignettes. This manuscript was supported by the University of Kansas College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Research Mini Retreat Grant and start-up funding. EXPECTATIONS OF TECHNOLOGY USE DURING MEETINGS 2 Abstract In organizational meetings mobile media are commonly used to hold multiple simultaneous conversations (i.e., multicommunication). This experiment uses video vignettes to test how manager policy (no policy, pro-technology, anti-technology), device-use (notepad, laptop, cell phone) and task-acknowledgement (no task-acknowledgement, task-acknowledgement) affect perceptions of meeting multicommunication behavior. U.S. workers (N = 243) who worked at least 30 hours per week and attended at least one weekly meeting rated relevant outcomes: expectancy violation, communicator evaluation, perceived competence, and meeting effectiveness. Results reveal manager policy and device-use both affect multicommunication perceptions with mobile phones generating the highest expectancy violation and lowest evaluation of the communicator and meeting effectiveness. Surprisingly, there was no effect for task-acknowledgment; however, a match between manager policy and task-acknowledgement affected evaluations. -

{FREE} a Song for the Dying

A SONG FOR THE DYING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stuart MacBride | 544 pages | 24 Mar 2015 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007344338 | English | London, United Kingdom A Song for the Dying PDF Book On "Song 32," she lays down her verses with a spoken-word clarity and stamina, and even pays ode to her rise declaring, "Started getting money from writing the haiku. Advertisement - Continue Reading Below. DC talent Ari Lennox 's brand of neo-soul is pretty and feminine, but nixes the idea that to be womanly means keeping quiet about the messy and personal. Rarely does she fail to take her greater aesthetic into consideration: For instance, her debut album Whack World , was a minute visual album odyssey inviting others into her obscure world. Eilish is the bad guy, and you damn well should be scared of this year-old because it's terrifying how talented she is, which she proves on hit. Synthesizers and Hatchie's hushed, yearning voice make "Stay With Me" euphoric, even as she recalls a romance that's ended. This cover of a Dire Straits song has managed to eclipse the original in pop culture, and doubles as a karaoke favorite. Here Birdman comes in handy as a useful example. We're more familiar with causes of death like heart attack , cancer and stroke. The translation sees dollar signs and the finer things in life on the singer's mind, but even as she ascends to pop domination, there's a cynicism to her tone over the upbeat song. It doesn't sound like disco in the slightest, but it sure is a movie-like party we're all longing for an invite to. -

Doja Cat Shares New Single and Video for “Tia Tamera” Ft

DOJA CAT SHARES NEW SINGLE AND VIDEO FOR “TIA TAMERA” FT. RICO NASTY CLICK HERE TO WATCH AMALA DELUXE ALBUM SET FOR RELEASE ON MARCH 1ST [New York, NY – February 20, 2019] Today, rapper/singer/songwriter/producer, Doja Cat releases her new single and accompanying video for “Tia Tamera” ft. Rico Nasty. She also announces that a deluxe version of her debut album Amala will be available everywhere on March 1st via RCA Records. Click HERE to listen. Produced by Doja Cat, the hard hitting, yet uncanny beat allows Doja to flex her lyrical abilities and implausible flow. “Tia Tamera” is the follow up to Doja’s viral hit, “Mooo!,” the hilarious tounge-in-cheek track and visual which garnered over 10 million views in just a few days on Twitter. With countless memes and celebrity co-signs including Chance The Rapper, Katy Perry, Khalid and Chris Brown, the video and track have been streamed over 60 million times worldwide. “Mooo!” was included in various “Best Of 2018” end of year lists including, NPR, Vulture, FADER and also earned Doja a spot in V Magazine’s “The New Generation in Music” feature in their current issue which focuses on rising musicians. Click HERE to see. Earlier last year Doja Cat released her debut album Amala, which NPR Music included in their “40 Favorite Albums of 2018.” They described the album as “…a manifesto of a young woman striving to take ownership of her craft, her image and her sexuality, mixing genres like dancehall, trap, house and R&B with a healthy dose of sass and humor…an unexpected pop gem…,” while PAPER exclaimed, “She’s about to be everywhere….