Searching for Wayang Golek: Islamic Rod Puppets and Chinese Woodwork in Java

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis on Symbolism of Malang Mask Dance in Javanese Culture

ANALYSIS ON SYMBOLISM OF MALANG MASK DANCE IN JAVANESE CULTURE Dwi Malinda (Corresponing Author) Departement of Language and Letters, Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jl. S Supriyadi 48 Malang, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 813 365 182 51 E-mail: [email protected] Sujito Departement of Language and Letters, Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jl. S Supriyadi 48 Malang, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 817 965 77 89 E-mail: [email protected] Maria Cholifa English Educational Department, Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jl. S Supriyadi 48 Malang, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 813 345 040 04 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Malang Mask dance is an example of traditions in Java specially in Malang. It is interesting even to participate. This study has two significances for readers and students of language and literature faculty. Theoretically, the result of the study will give description about the meaning of symbols used in Malang Mask dance and useful information about cultural understanding, especially in Javanese culture. Key Terms: Study, Symbol, Term, Javanese, Malang Mask 82 In our every day life, we make a contact with culture. According to Soekanto (1990:188), culture is complex which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society. Culture are formed based on the local society and become a custom and tradition in the future. Culture is always related to language. This research is conducted in order to answer the following questions: What are the symbols of Malang Mask dance? What are meannings of those symbolism of Malang Mask dance? What causes of those symbolism used? What functions of those symbolism? REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE Language Language is defined as a means of communication in social life. -

Bab I Pendahuluan

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Latar Belakang Masalah KetikabangsaIndonesiabersepakatuntukmemproklamasikankemerdeka an Indonesia pada tanggal 17 Agustus 1945, para bapak pendiribangsa (the founding father) menyadari bahwa paling tidak ada tigatantangan besar yang harus dihadapi. Tantangan yang pertama adalahmendirikan negara yang bersatu dan berdaulat. Tantangan yang keduaadalah membangun bangsa. Dan tantangan yang ketiga adalah membangunkarakter. Ketiga hal tersebut secara jelas tampak dalam konsep negarabangsa (nation-state) dan pembangunan karakter bangsa (nation andcharacter building). Pada implementasinya kemudian upaya mendirikannegara relatif lebih cepat jika dibandingkan dengan upaya untukmembangun bangsa dan karakter. Kedua hal terakhir itu terbukti harusdiupayakan terus-menerus, tidak boleh putus di sepanjang sejarah kehidupankebangsaan Indonesia. 1 Dan dalam hemat penulis, salah satu langkah untukmembangun bangsa dan karakter ialah dengan pendidikan. Banyak kalangan memberikan makna tentang pendidikan sangatberagam, bahkan sesuai dengan pandangannya masing-masing. AzyumardiAzra memberikan pengertian tentang “pendidikan” adalah merupakan suatuproses dimana suatu bangsa mempersiapkan generasi mudanya untukmenjalankan kehidupan dan untuk memenuhi tujuan hidup 1 2 secara efektif dan efisien. Bahkan ia menegaskan, bahwa pendidikan adalah suatu proses dimana suatu bangsa atau negara membina dan mengembangkan kesadaran diri diantara individu-individu.2 Di samping itu penddikan adalah suatu hal yang benar-benarditanamkan selain menempa fisik, mental, dan moral bagi individu-individu, agar mereka mejadi manusia yang berbudaya sehingga diharapkanmampu memenuhi tugasnya sebagai manusia yang diciptakan Allah TuhanSemesta Alam, sebagai makhluk yang sempurna dan terpilih sebagaikhalifah-Nya di muka bumi ini yang sekaligus menjadi warga negara 3 yangberarti dan bermanfaat bagi suatu negara. Bangkitnya dunia pendidikan yang dirintis oleh Pahlawan kita Ki HajarDewantara untuk menentang penjajah pada masa lalu, sungguh sangatberarti apabila kita cermati dengan seksama. -

Sistem Ekonomi Dan Dampak Sosial Di Sekitar Masjid Sunan Ampel Surabaya

SISTEM EKONOMI DAN DAMPAK SOSIAL DI SEKITAR MASJID SUNAN AMPEL SURABAYA Disusun oleh : Drs. Edy Yusuf Nur SS, MM., M.Si., M.BA. MANAJEMEN PENDIDIKAN ISLAM FAKULTAS ILMU TARBIYAH DAN KEGURUAN UIN SUNAN KALIJAGA YOGYAKARTA 2017 KATA PENGANTAR Assalamualaikum. Wr. Wb. Puji syukur kami panjatkan kehadirat Allah SWT atas limpahan rahmat dan hidayah-Nya. Sehingga penulis dapat menyelesaikan Penelitian Sistem Ekonomi dan Dampak Sosial di Sekitar Masjid Sunan Ampel Surabaya dengan baik. Penulis mengucapkan banyak terimakasih kepada pihak-pihak yang sudah membantu dalam Penelitian ini. Penulis juga menyadari bahwa Penelitian ini masih kurang dari kata sempurna Oleh karena itu, penulis senantiasa menanti kritik dan saran yang membangun dari semua pihak guna penyempurnaan Penelitian ini. Penulis berharap Penelitian ini dapat memberi apresiasi kepada para pembaca dan utamanya kepada penulis sendiri. Selain itu semoga Penelitian ini dapat memberi manfaat kepada para pembaca. Wassalamualaikum. Wr. Wb. Yogyakarta, 31 Desember 2017 Penyusun BAB I PENDAHULUAN I. LATAR BELAKANG Jawa Timur adalah sebuah provinsi di bagian timur Pulau Jawa, Indonesia dengan ibukotanya adalah Surabaya. Besar dan luas wilayah kota adalah sekitar 326.38 km2, keseluruhan seluas 47.922 km² dengan jumlah penduduk sekitar 37.070.731 jiwa. Provinsi Jawa Timur memiliki wilayah terluas di antara 6 provinsi di Pulau Jawa, dan memiliki jumlah penduduk terbanyak kedua di Indonesia setelah Jawa Barat. Jawa Timur dikenal sebagai pusat Kawasan Timur Indonesia, dan memiliki signifikansi perekonomian yang cukup tinggi, yakni berkontribusi 14,85% terhadap Produk Domestik Bruto nasional. (BPS Surabaya, 2010) Surabaya sebagai ibukota Provinsi Jawa Timur memiliki banyak bangunan serta kawasan bersejarah, yang wajib dipelihara dan dilestarikan melalui kegiatan konservasi. -

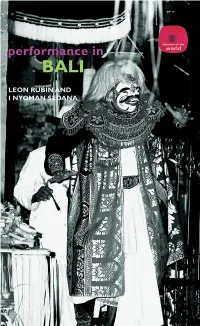

Performance in Bali

Performance in Bali Performance in Bali brings to the attention of students and practitioners in the twenty-first century a dynamic performance tradition that has fasci- nated observers for generations. Leon Rubin and I Nyoman Sedana, both international theatre professionals as well as scholars, collaborate to give an understanding of performance culture in Bali from inside and out. The book describes four specific forms of contemporary performance that are unique to Bali: • Wayang shadow-puppet theatre • Sanghyang ritual trance performance • Gambuh classical dance-drama • the virtuoso art of Topeng masked theatre. The book is a guide to current practice, with detailed analyses of recent theatrical performances looking at all aspects of performance, production and reception. There is a focus on the examination and description of the actual techniques used in the training of performers, and how some of these techniques can be applied to Western training in drama and dance. The book also explores the relationship between improvisation and rigid dramatic structure, and the changing relationships between contemporary approaches to performance and traditional heritage. These culturally unique and beautiful theatrical events are contextualised within religious, intel- lectual and social backgrounds to give unparalleled insight into the mind and world of the Balinese performer. Leon Rubin is Director of East 15 Acting School, University of Essex. I Nyoman Sedana is Professor at the Indonesian Arts Institute (ISI) in Bali, Indonesia. Contents List -

Digital Islam in Indonesia: the Shift of Ritual and Religiosity During Covid-19

ISSUE: 2021 No. 107 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 12 August 2021 Digital Islam in Indonesia: The Shift of Ritual and Religiosity during Covid-19 Wahyudi Akmaliah and Ahmad Najib Burhani* Covid-19 has forced various Muslim groups to adopt digital platforms in their religious activities. Controversy, however, abounds regarding the online version of the Friday Prayer. In Islamic law, this ritual is wajib (mandatory) for male Muslims. In this picture, Muslims observe Covid-19 coronavirus social distancing measures during Friday prayers at Agung mosque in Bandung on 2 July 2021. Photo: Timur Matahari, AFP. * Wahyudi Akmaliah is a PhD Student at the Malay Studies Department, National University of Singapore (NUS). Ahmad Najib Burhani is Visiting Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute and Research Professor at the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Jakarta. The authors wish to thank Lee Sue-Ann and Norshahril Saat for their comments and suggestions on this article. 1 ISSUE: 2021 No. 107 ISSN 2335-6677 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the use of digital platforms in religious rituals was already becoming an increasingly common practice among Indonesian preachers to reach out to young audiences. During the pandemic, some Muslim organisations and individual preachers have speeded up the use of such platforms as a way to communicate with people and to continue with religious practices among the umma. • Among religious rituals that have shifted online are the virtual tahlil (praying and remembering dead person), silaturahim (visiting each other) during Eid al-Fitr, haul (commemorating the death of someone), and tarawih (night prayer during Ramadan). -

Kontribusi Sunan Ampel (Raden Rahmat) Dalam Pendidikan Islam

KONTRIBUSI SUNAN AMPEL (RADEN RAHMAT) DALAM PENDIDIKAN ISLAM Muslimah1, Lailatul Maskhuroh2 [email protected] Abstrak : Umat Islam merupakan mayoritas penduduk Asia Tenggara, khususnya di Indonesia, Malaysia, Pattani (Thailand Selatan) dan Brunei. Proses konversi massal masyarakat dunia Melayu-Indonesia ke dalam Islam berlangsung secara damai. Konversi ke dalam Islam merupakan proses panjang, yang masih terus berlangsung sampai sekarang. Islamisasi itu lebih intens dan luas sejak akhir abad ke-12. Meskipun terjadi beberapa teori tentang kedatangan Islam di Asia tenggara, bahwa pedagang muslim dari kawasan Jazirah Arab telah hadir di beberapa tempat di Nusantara, sejak abad ke-7 akan tetapi tidak ada bukti yang memadai bahwa mereka memusatkan diri pada kegiatan penyebaran Islam di Indonesia.3 Ulama menjadi salah satu yang punya peran penyebaran Islam di nusantara, karena nusantara pada awalnya berbentuk kerajaan-kerajaan. Dengan penyebaranIslam secara massif (dengan pernikahan putri majapahit dan melalui adat budaya masyarakat setempat,akulturasi nilai-nilai Islam sampai pada masyarakat secara luas). Adapun kontribusi sunan Ampel dalam pendidikan Islam adalah :a). Fungsi pendidikan inspiratif untuk Fungsi ini lebih menekankan pada fungsi traditional sebagai fungsi konservator budaya. Dalam fungsi ini, Sunan Ampel memberikan warna Islami terhadap tradisi yang berlaku dimasyarakat. b). Tujuannya berupa memperbaiki moral dan mengajak masyarakat untuk beriman kepada Allah. Sebelum mengajak masyarakat masuk Islam, Sunan Ampel terlebih dahulu mengajak penguasa Majapahit untuk masuk Islam c). Unsur pendidikan Islam yaitu pendidik sebagai fasilitator, dan sunan Ampel menggunakan metode demonstrasi atau eksperimen dan metode insersi atau sisipan. Kata Kunci: Kontribusi, Sunan Ampel, Pendidikan Islam 1 Alumni STIT al Urwatul Wutsqo Jombang 2 Dosen Tetap STIT al Urwatul Wutsqo Jombang 3 Rahmawati, Islam Di Asia Tenggara, Jurnal Rihlah Vol.II No.I 2014, 104. -

2477-6866, P-ISSN: 2527-9416 Vol. 6, No.2, July 2021, Pp

International Review of Humanities Studies www.irhs.ui.ac.id, e-ISSN: 2477-6866, p-ISSN: 2527-9416 Vol. 6, No.2, July 2021, pp. 917-931 ABANG-NONE AS AN ATTEMPT OF THE GOVERNMENT TO INTRODUCE THE BETAWI CULTURE TO THE WORLD Bariq Mughniy Waliyyayasi Depok, West Java, Indonesia [email protected] ABSTRACT The Abang and None Competition is a media of the DKI Jakarta Tourism Office to introduce Betawi culture to the world. Betawi culture is the pride of the people of Jakarta, namely as the identity of the main area within the scope of its society. The competition has various functions, not only as entertainment but also as a medium for promoting Jakarta tourism. This has various problems, including the lack of knowledge about Jakarta. Most people outside Jakarta only know Jakarta to be the capital of Indonesia. They do not have any knowledge about the authentic and unique culture of Jakarta that emerged because the interaction of people from various regions living there. With the presence of the Abang and None Competition, it is hoped that they will be able to raise the slogan "Enjoy Jakarta" to become increasingly popular and can attract outsiders to want to visit Jakarta. So what does the government expect to achieve through the competition? How does the government plan to use the Competition to promote Betawi culture internationally? This article will discuss those efforts and how effective they are. Qualitative descriptive methods will be the key in this research. KEYWORDS : Abang-None, Betawi Culture, Enjoy Jakarta, Jakarta Tourism INTRODUCTION Jakarta is not only the capital city of Indonesia, but it is also a tourist destination. -

A Case Study of Topeng Tua Dance)

HARMONIA : Journal of Arts Research and Education 15 (2) (2015), 107-112 p-ISSN 1411-5115 Available online at http://journal.unnes.ac.id/nju/index.php/harmonia e-ISSN 2355-3820 DOI: 10.15294/harmonia.v15i2.4557 TAKSU AND PANGUS AS AN AESTHETIC CONCEPT ENTITY OF BALI DANCE (A Case Study of Topeng Tua Dance) I Nengah Mariasa Department of Drama, Dance, and Music, State University of Surabaya Lidah Wetan Surabaya, Surabaya 61177, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 28, 2015. Revised: November 30, 2015. Accepted: December 4, 2015 Abstract There are two types of topeng drama performance (topeng is Bahasa Indonesia for mask) in Bali, Topeng Pajegan and Topeng Panca. Topeng Pajegan is a masked drama performance that is danced by a dancer by playing various tapel, while Topeng Panca is danced by five dancers. Generally, there are three or four stages on topeng performance, i.e. panglembar, petangkilan, bebondresan, and/or pesiat. On panglembar stage, there is one dance represented the character of old people. The dance is then known as Topeng Tua (Old Mask). The costume, tapel, as well as hair worn by the dancer have been considered as one of the precious or noble artworks. The question comes up here, is the aesthetics of topeng only depended on its high aesthetic value costume and tapel? Topeng Tua performance technique is considerably not easy to be done by a beginner dancer. On the other words, it implicitly tells that the aesthetics of the dance depends closely to the dancers’ techniques. A good Topeng Tua dancer will be able to dance by using the technique of ngigelang topeng. -

The Legitimacy of Classical Dance Gagrag Ngayogyakarta

The Legitimacy of Classical Dance Gagrag Ngayogyakarta Y. Sumandiyo Hadi Institut Seni Indonesia (ISI) Yogyakarta Jalan Parangtritis Km 6,5, Sewon, Bantul Yogyakarta ABSTRACT The aim of this article is to reveal the existence of classical dance style of Yogyakarta, since the government of Sultan Hamengku Buwono I, which began in 1756 until now in the era the government of Sultan Hamengku Buwono X. The legitimation of classical dance is considered as “Gagrag Ngayogyakarta”. Furthermore, the dance is not only preserved in the palace, but living and growing outside the palace, and possible to be examined by the general public. The dance was fi rst considered as a source of classical dance “Gagrag Ngayogyakarta”, created by Sultan Hamengku Buwono I, i.e. Beksan Lawung Gagah, or Beksan Trunajaya, Wayang Wong or dance drama, and Bedaya dance. The three dances can be categorized as a sacred dance, in which the performances strongly related to traditional ceremonies or rituals. Three types of dance later was developed into other types of classical dance “Gagrag Ngayogyakarta”, which is categorized as a secular dance for entertainment performance. Keywords: Sultan Hamengku Buwono, classical dance, “gagrag”, Yogyakarta style, legitimacy, sacred, ritual dance, secular dance INTRODUCTION value because it is produced by qualifi ed Yogyakarta as one of the regions in the artists from the upper-middle-class society, archipelago, which has various designa- and not from the proletarians or low class. tions, including a student city, a tourism The term of tradition is a genre from the city, and a cultural city. As a cultural city, past, which is hereditary from one gene- there are diff erent types of artwork. -

Mengislamkan Tanah Jawa Walisongo

Wahana Akademika Wahana Akademika 243 Vol. 1 No. 2, Oktober 2014, 243 –266 WALISONGO: MENGISLAMKAN TANAH JAWAWALISONGO: JAWA Suatu Kajian PustakaSuatu Pustaka Dewi Evi AnitaDewi Anita SETIA Walisembilan Semarang Email: [email protected] The majority of Indonesian Islamic . In Javanese society, Walisongo designation is a very well known name and has a special meaning, which is used to refer to the names of the characters are seen as the beginning of broadcasting Islam in Java. The role of the mayor is very big on the course of administration of the empire, especially the Sultanate of Demak. Method development and broadcasting of Islam which is taken for the Mayor prioritizes wisdom. Closing the rulers and the people directly to show the goodness of Islam, giving examples of noble character in everyday life as well as adjusting the conditions and situation of the local community, so it is not the slightest impression of Islam was developed by the Mayor with violence and coercion. Stories of the Guardians is not taken for granted, but the stories of the Guardians of the charismatic deliberately created to elevate the trustees. KeywordKeywordKeywordsKeywordsss:: peranan, metode pengembangan dan penyiaran Islam, kharisma, Walisongo 244 Dewi Evi Anita A.A.A. Pendahuluan Penyebaran dan perkembangan Islam di Nusatara dapat dianggap sudah terjadi pada tahun-tahun awal abad ke-12 M. Berdasarkan data yang telah diteliti oleh pakar antropologi dan sejarah, dapat diketahui bahwa penyiaran Islam di Nusantara tidak bersamaan waktunya, demikian pula kadar pengaruhnya berbeda-beda di suatu daerah. Berdasarkan konteks sejarah kebudayaan Islam di Jawa, rentangan waktu abad ke-15 sampai ke-16 ditandai tumbuhnya suatu kebudayaan baru yang menampilkan sintesis antara unsur kebudayaan Hindu-Budha dengan unsur kebudayaan Islam. -

M. Van Bruinessen Najmuddin Al-Kubra, Jumadil Kubra and Jamaluddin Al-Akbar; Traces of Kubrawiyya Influence in Early Indonesian Islam

M. van Bruinessen Najmuddin al-Kubra, Jumadil Kubra and Jamaluddin al-Akbar; Traces of Kubrawiyya influence in early Indonesian islam In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 150 (1994), no: 2, Leiden, 305-329 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 02:48:13PM via free access MARTIN VAN BRUINESSEN Najmuddin al-Kubra, Jumadil Kubra and Jamaluddin al-Akbar Traces of Kubrawiyya Influence in Early Indonesian Islam The Javanese Sajarah Banten rante-rante (hereafter abbreviated as SBR) and its Malay translation Hikayat Hasanuddin, compiled in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century but incorporating much older material, consist of a number of disparate narratives, one of which tells of the alleged studies of Sunan Gunung Jati in Mecca.1 A very similar, though less detailed, account is contained in the Brandes-Rinkes recension of the Babad Cirebon. Sunan Gunung Jati, venerated as one of the nine saints of Java, is a historical person, who lived in the first half of the 16th century and founded the Muslim kingdoms of Banten and Cirebon. Present tradition gives his proper name as Syarif Hidayatullah; the babad literature names him variously as Sa'ad Kamil, Muhammad Nuruddin, Nurullah Ibrahim, and Maulana Shaikh Madhkur, and has him born either in Egypt or in Pasai, in north Sumatra. It appears that a number of different historical and legendary persons have merged into the Sunan Gunung Jati of the babad. Sunan Gunung Jati and the Kubrawiyya The historical Sunan Gunung Jati may or may not have actually visited Mecca and Medina. -

Performance in Bali

Performance in Bali Performance in Bali brings to the attention of students and practitioners in the twenty-first century a dynamic performance tradition that has fasci- nated observers for generations. Leon Rubin and I Nyoman Sedana, both international theatre professionals as well as scholars, collaborate to give an understanding of performance culture in Bali from inside and out. The book describes four specific forms of contemporary performance that are unique to Bali: • Wayang shadow-puppet theatre • Sanghyang ritual trance performance • Gambuh classical dance-drama • the virtuoso art of Topeng masked theatre. The book is a guide to current practice, with detailed analyses of recent theatrical performances looking at all aspects of performance, production and reception. There is a focus on the examination and description of the actual techniques used in the training of performers, and how some of these techniques can be applied to Western training in drama and dance. The book also explores the relationship between improvisation and rigid dramatic structure, and the changing relationships between contemporary approaches to performance and traditional heritage. These culturally unique and beautiful theatrical events are contextualised within religious, intel- lectual and social backgrounds to give unparalleled insight into the mind and world of the Balinese performer. Leon Rubin is Director of East 15 Acting School, University of Essex. I Nyoman Sedana is Professor at the Indonesian Arts Institute (ISI) in Bali, Indonesia. Theatres of the World Series editor: John Russell Brown Series advisors: Alison Hodge, Royal Holloway, University of London; Osita Okagbue, Goldsmiths College, University of London Theatres of the World is a series that will bring close and instructive contact with makers of performances from around the world.