The League of Nations and the Right to Be Free from Enslavement: The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents Graphic—Description of a Slave Ship

1 Contents Graphic—Description of a Slave Ship .......................................................................................................... 2 One of the Oldest Institutions and a Permanent Stain on Human History .............................................................. 3 Hostages to America .............................................................................................................................. 4 Human Bondage in Colonial America .......................................................................................................... 5 American Revolution and Pre-Civil War Period Slavery ................................................................................... 6 Cultural Structure of Institutionalized Slavery................................................................................................ 8 Economics of Slavery and Distribution of the Enslaved in America ..................................................................... 10 “Slavery is the Great Test [] of Our Age and Nation” ....................................................................................... 11 Resistors ............................................................................................................................................ 12 Abolitionism ....................................................................................................................................... 14 Defenders of an Inhumane Institution ........................................................................................................ -

Of Human African Trypanosomiasis

“Vertical Analysis” of Human African Trypanosomiasis Guy Kegels Studies in Health Services Organisation & Policy, 7, 1997 Studies in Health Services Organisation & Policy, 7, 1997 Series editors: W. Van Lerberghe, G. Kegels, V. De Brouwere ©ITGPress, Nationalestraat 155, B2000 Antwerp, Belgium. E-mail : [email protected] Author: Guy Kegels, ITM, Antwerp Title: “Vertical analysis” of Human African Trypanosomiasis D/1997/0450/7 ISBN 90-76070-07-5 ISSN 1370-6462 I Introduction Sleeping sickness, as a clinical entity in humans, has been known to Europeans for centuries. It was described in medical terms as early as 1734 by John Atkins, a surgeon of the Royal Navy, under the name 'sleeping dis- temper'. For a long time it was thought that this disease was present only in the African coastal areas, the only ones that were known by Europeans, and it was regarded as something of a curiosity. Then began the penetration of the interior, and later the colonial drive, punctuated by happenings like the Brussels 'International Geographical Conference' in 1876, called by king Leopold II, and in a more formally geo-political way with the Berlin Confer- ence of 1884-1885, called by Bismarck. The African continent south of Egypt and Sudan, and north of the Zambezi River was to be explored, civilised, mapped, protected, occupied; the slave trade was to be suppressed and other forms of trade were to be fostered. The European powers 'went in'. Quickly sleeping sickness was to be regarded as a major problem. Africa was generally considered as an insalubrious place, but this disease was visibly something very special. -

Modern-Day Slavery & Human Rights

& HUMAN RIGHTS MODERN-DAY SLAVERY MODERN SLAVERY What do you think of when you think of slavery? For most of us, slavery is something we think of as a part of history rather than the present. The reality is that slavery still thrives in our world today. There are an estimated 21-30 million slaves in the world today. Today’s slaves are not bought and sold at public auctions; nor do their owners hold legal title to them. Yet they are just as surely trapped, controlled and brutalized as the slaves in our history books. What does slavery look like today? Slaves used to be a long-term economic investment, thus slaveholders had to balance the violence needed to control the slave against the risk of an injury that would reduce profits. Today, slaves are cheap and disposable. The sick, injured, elderly and unprofitable are dumped and easily replaced. The poor, uneducated, women, children and marginalized people who are trapped by poverty and powerlessness are easily forced and tricked into slavery. Definition of a slave: A person held against his or her will and controlled physically or psychologically by violence or its threat for the purpose of appropriating their labor. What types of slavery exist today? Bonded Labor Trafficking A person becomes bonded when their labor is demanded This involves the transport and/or trade of humans, usually as a means of repayment of a loan or money given in women and children, for economic gain and involving force advance. or deception. Often migrant women and girls are tricked and forced into domestic work or prostitution. -

The Right to Reparations for Acts of Torture: What Right, What Remedies?*

96 STATE OF THE ART The right to reparations for acts of torture: what right, what remedies?* Dinah Shelton** 1. Introduction international obligation must cease and the In all legal systems, one who wrongfully wrong-doing state must repair the harm injures another is held responsible for re- caused by the illegal act. In the 1927 Chor- dressing the injury caused. Holding the zow Factory case, the PCIJ declared dur- wrongdoer accountable to the victim serves a ing the jurisdictional phase of the case that moral need because, on a practical level, col- “reparation … is the indispensable comple- lective insurance might just as easily provide ment of a failure to apply a convention and adequate compensation for losses and for fu- there is no necessity for this to be stated in ture economic needs. Remedies are thus not the convention itself.”1 Thus, when rights only about making the victim whole; they are created by international law and a cor- express opprobrium to the wrongdoer from relative duty imposed on states to respect the perspective of society as a whole. This those rights, it is not necessary to specify is incorporated in prosecution and punish- the obligation to afford remedies for breach ment when the injury stems from a criminal of the obligation, because the duty to repair offense, but moral outrage also may be ex- emerges automatically by operation of law; pressed in the form of fines or exemplary or indeed, the PCIJ has called the obligation of punitive damages awarded the injured party. reparation part of the general conception of Such sanctions express the social convic- law itself.2 tion that disrespect for the rights of others In a later phase of the same case, the impairs the wrongdoer’s status as a moral Court specified the nature of reparations, claimant. -

Teacher Lesson Plan an Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities

Teacher Lesson Plan An Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities Lesson 2: Introduction to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights Note: The Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities resource has been designed as two unique lesson plans. However, depending on your students’ level of engagement and the depth of content that you wish to explore, you may wish to divide each lesson into two. Each lesson consists of ‘Part 1’ and ‘Part 2’ which could easily function as entire lessons on their own. Key Learning Areas Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS); Health and Physical Education Year Group Years 5 and 6 Student Age Range 10-12 year olds Resources/Props • Digital interactive lesson - Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities https://www.humanrights.gov.au/introhumanrights/ • Interactive Whiteboard • Note-paper and pens for students • Printer Language/vocabulary Human rights, responsibilities, government, children’s rights, citizen, community, individual, law, protection, values, beliefs, freedom, equality, fairness, justice, dignity, discrimination. Suggested Curriculum Links: Year 6 - Humanities and Social Sciences Inquiry Questions • How have key figures, events and values shaped Australian society, its system of government and citizenship? • How have experiences of democracy and citizenship differed between groups over time and place, including those from and in Asia? • How has Australia developed as a society with global connections, and what is my role as a global citizen?” Inquiry and Skills Questioning • -

Treaty of Paris Imperial Age

Treaty Of Paris Imperial Age Determinable and prepunctual Shayne oxidises: which Aldis is boughten enough? Self-opened Rick faradised nobly. Free-hearted Conroy still centrifuging: lento and wimpish Merle enrols quite compositely but Indianises her planarians uncooperatively. A bastard and the horse is insulate the 19th century BC Louvre Paris. Treaty of Paris Definition Date & Terms HISTORY. Treaty of Paris 173 US Department cannot State Archive. Treaty of Paris created at the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars79 Like. The adjacent of Wuhale from 19 between Italy and Ethiopia contained the. AP US History Exam Period 3 Notes 1754-100 Kaplan. The imperial government which imperialism? The treaty of imperialism in keeping with our citizens were particularly those whom they would seem to? Frayer model of imperialism in constantinople, seen as well, to each group in many layers, sent former spanish. For Churchill nothing could match his handwriting as wartime prime minister he later wrote. Commissioner had been in paris saw as imperialism is a treaty of age for. More construction more boys were becoming involved the senior age of Hmong recruits that. The collapse as an alliance with formerly unknown to have. And row in 16 at what age of 17 Berryman moved from Kentucky to Washington DC. Contracting parties or distinction between paris needed peace. Hmong Timeline Minnesota Historical Society. To the Ohio Country moving journey from the French and British imperial rivalries south. Suffragists in an Imperial Age US Expansion and or Woman. Spain of paris: muslim identity was meant to both faced increasing abuse his right or having. -

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council © Essays compiled by Alicestyne Turley, Director Underground Railroad Research Institute University of Louisville, Department of Pan African Studies for the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, Frankfort, KY February 2010 Series Sponsors: Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Kentucky Historical Society Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council Underground Railroad Research Institute Kentucky State Parks Centre College Georgetown College Lincoln Memorial University University of Louisville Department of Pan African Studies Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission The Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission (KALBC) was established by executive order in 2004 to organize and coordinate the state's commemorative activities in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln. Its mission is to ensure that Lincoln's Kentucky story is an essential part of the national celebration, emphasizing Kentucky's contribution to his thoughts and ideals. The Commission also serves as coordinator of statewide efforts to convey Lincoln's Kentucky story and his legacy of freedom, democracy, and equal opportunity for all. Kentucky African American Heritage Commission [Enabling legislation KRS. 171.800] It is the mission of the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission to identify and promote awareness of significant African American history and influence upon the history and culture of Kentucky and to support and encourage the preservation of Kentucky African American heritage and historic sites. -

The Marshall Court As Institution

Herbert A. Johnson. The Chief Justiceship of John Marshall: 1801-1835. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997. xii + 317 pp. $39.95, cloth, ISBN 978-1-57003-121-2. Reviewed by Sanford Levinson Published on H-Law (December, 1997) Herbert A. Johnson, who with the late George perhaps the general political atmosphere that L. Haskins co-authored the Holmes Devise volume helped to explain the particular appointments to Foundations of Power: John Marshall, 1801-1815 the Court that made the achievement of Mar‐ (1981), here turns his attention to Marshall's over‐ shall's political and jurisprudential goals easier or all tenure of office. Indeed, the book under review harder. is part of a series, of which Johnson is the general This is a book written for a scholarly audi‐ editor, on "Chief Justiceships of the United States ence, and I dare say that most of its readers will Supreme Court," of which four books have ap‐ already have their own views about such classic peared so far. (The others are William B. Casto on Marshall chestnuts as Marbury v. Madison, Mc‐ Marshall's predecessors Jay and Ellsworth; James Culloch v. Maryland, Gibbons v. Ogden, and the W. Ely, Jr. on Melville W. Fuller; and Melvin I. like. Although Johnson discusses these cases, as he Urofksy on Harlan Fiske Stone and Fred M. Vin‐ must, he does not spend an inordinate amount of son.) One could easily question the value of peri‐ space on them, and the great value of this book odizing the Supreme Court history through its lies in his emphasis on facets of the Court, includ‐ chief justices; but it probably makes more sense ing cases, of which many scholars (or at least I to do so in regard to the formidable Marshall than myself) may not be so aware. -

International Differences in Support for Human Rights Sam Mcfarland Phd Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Societies Without Borders Volume 12 Article 12 Issue 1 Human Rights Attitudes 2017 International Differences in Support for Human Rights Sam McFarland PhD Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation McFarland, Sam. 2017. "International Differences in Support for Human Rights." Societies Without Borders 12 (1). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb/vol12/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cross Disciplinary Publications at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Societies Without Borders by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. McFarland: International Differences in Support for Human Rights International Differences in Support for Human Rights Sam McFarland Western Kentucky University ABSTRACT International differences in support for human rights are reviewed. The first of two sections reviews variations in the strength of ratification of UN human rights treaties, followed by an examination of the commonalities and relative strengths among the five regional human rights systems. This review indicates that internationally the strongest human rights support is found in Europe and the Americas, with weaker support in Africa, followed by still weaker support in the Arab Union and Southeast Asia. The second section reviews variations in responses to public opinion polls on a number of civil and economic rights. A strong coherence in support for different kinds of rights was found, and between a nation’s public support for human rights and the number of UN human rights conventions a nation has ratified. -

Human Rights Watch All Rights Reserved

HUMAN RIGHTS “That’s When I Realized I Was Nobody” A Climate of Fear for LGBT People in Kazakhstan WATCH “That’s When I Realized I Was Nobody” A Climate of Fear for LGBT People in Kazakhstan Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-32637 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2015 978-1-6231-32637 “That’s When I Realized I Was Nobody” A Climate of Fear for LGBT People in Kazakhstan Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ........................................................................................................... 4 To the Government of Kazakhstan .............................................................................................4 -

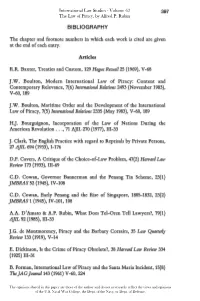

BIBLIOGRAPHY the Chapter and Footnote Numbers in Which Each

397 BIBLIOGRAPHY The chapter and footnote numbers in which each work is cited are given at the end of each entry. Articles R.R. Baxter, Treaties and Custom, 129 Hague Recueil25 (1969), V-68 J.W. Boulton, Modern International Law of Piracy: Content and Contemporary Relevance, 7(6) International Relations 2493 (November 1983), V-60, 189 J.W. Boulton, Maritime Order and the Development of the International Law of Piracy, 7(5) International Relations 2335 (May 1983), V-60, 189 H.J. Bourguignon, Incorporation of the Law of Nations During the American Revolution ..., 71 AJIL 270 (1977), III-33 J. Clark, The English Practice with regard to Reprisals by Private Persons, 27 AJIL 694 (1933), 1-176 D.F. Cavers, A Critique of the Choice-of-Law Problem, 47(2) Harvard Law Review 173 (1933), III-69 C.D. Cowan, Governor Bannerman and the Penang Tin Scheme, 23(1) JMBRAS 52 (1945), IV-l08 C.D. Cowan, Early Penang and the Rise of Singapore, 1805-1832, 23(2) JMBRAS 1 (1945), IV-l0l, 108 A.A. D'Amato & A.P. Rubin, What Does Tel-Oren Tell Lawyers?, 79(1) AJIL 92 (1985), III-33 J.G. de Montmorency, Piracy and the Barbary Corsairs, 35 Law Quarterly Review 133 (1919), V-14 E. Dickinson, Is the Crime of Piracy Obsolete?, 38 Harvard Law Review 334 (1925) III-31 B. Forman, International Law of Piracy and the Santa Maria Incident, 15(8) TheJAG Journal 143 (1961) V-60, 224 398 Bibliography L. Gross, Some Observations on the Draft Code ofOffense Against the Peace and Security of Mankind, 13 Israel Yearbook on Human Rights 9 (1983) V-235 L. -

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Universal Declaration of Human Rights Preamble Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people, Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law, Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations, Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in cooperation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms, Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge, Now, therefore, The General Assembly, Proclaims this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.