The Marshall Court As Institution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Political Effects of the Addition of Judgeships to the United States Supreme Court Following Electoral Realignments

A Compliant Court: The Political Effects of the Addition of Judgeships to the United States Supreme Court Following Electoral Realignments Lauren Paige Joyce Judson Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts In Political Science Jason P. Kelly, Chair Wayne D. Moore Karen M. Hult August 7, 2014 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Judicial Politics, Electoral Realignment, Alteration to the Supreme Court Copyright 2014, Lauren J. Judson A Compliant Court: The Political Effects of the Addition of Judgeships to the United States Supreme Court Following Electoral Realignments Lauren J. Judson ABSTRACT During periods of turmoil when ideological preferences between the federal branches of government fail to align, the relationship between the three quickly turns tumultuous. Electoral realignments especially have the potential to increase tension between the branches. When a new party replaces the “old order” in both the legislature and the executive branches, the possibility for conflict emerges with the Court. Justices who make decisions based on old regime preferences of the party that had appointed them to the bench will likely clash with the new ideological preferences of the incoming party. In these circumstances, the president or Congress may seek to weaken the influence of the Court through court-curbing methods. One example Congress may utilize is changing the actual size of the Supreme The size of the Supreme Court has increased four times in United States history, and three out of the four alterations happened after an electoral realignment. Through analysis of Supreme Court cases, this thesis seeks to determine if, after an electoral realignment, holdings of the Court on issues of policy were more congruent with the new party in power after the change in composition as well to examine any change in individual vote tallies of the justices driven by the voting behavior of the newly appointed justice(s). -

Just Because John Marshall Said It, Doesn't Make It So: Ex Parte

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2000 Just Because John Marshall Said it, Doesn't Make it So: Ex Parte Bollman and the Illusory Prohibition on the Federal Writ of Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners in the Judiciary Act of 1789 Eric M. Freedman Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Eric M. Freedman, Just Because John Marshall Said it, Doesn't Make it So: Ex Parte Bollman and the Illusory Prohibition on the Federal Writ of Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners in the Judiciary Act of 1789, 51 Ala. L. Rev. 531 (2000) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/53 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MILESTONES IN HABEAS CORPUS: PART I JUST BECAUSE JOHN MARSHALL SAID IT, DOESN'T MAKE IT So: Ex PARTE BoLLMAN AND THE ILLUSORY PROHIBITION ON THE FEDERAL WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS FOR STATE PRISONERS IN THE JUDIcIARY ACT OF 1789 Eric M. Freedman* * Professor of Law, Hofstra University School of Law ([email protected]). BA 1975, Yale University;, MA 1977, Victoria University of Wellington (New Zea- land); J.D. 1979, Yale University. This work is copyrighted by the author, who retains all rights thereto. -

Not the King's Bench Edward A

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Constitutional Commentary 2003 Not the King's Bench Edward A. Hartnett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hartnett, Edward A., "Not the King's Bench" (2003). Constitutional Commentary. 303. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm/303 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Constitutional Commentary collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOT THE KING'S BENCH Edward A. Hartnett* Speaking at a public birthday party for an icon, even if the honoree is one or two hundred years old, can be a surprisingly tricky business. Short of turning the party into a roast, it seems rude to criticize the birthday boy too harshly. On the other hand, it is at least as important to avoid unwarranted and exaggerated praise.1 The difficult task, then, is to try to say something re motely new or interesting while navigating that strait. The conference organizers did make it easier for me in one respect: My assignment does not involve those ideas for which Marbury is invoked as an icon. It is for others to wrestle in well worn trenches with exalted arguments about judicial review and its overgrown descendent judicial supremacy, while trying to avoid unseemly criticism or fawning praise. I, on the other hand, am to address more technical issues involving section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 and its provision granting the Supreme Court the power to issue writs of mandamus. -

Adhering to Our Views: Brennan and Marshall and the Relentless Dissent to Death As a Punishment

Florida State University Law Review Volume 22 Issue 3 Article 1 1995 Adhering to Our Views: Brennan and Marshall and the Relentless Dissent to Death as a Punishment Michael Mello [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael Mello, Adhering to Our Views: Brennan and Marshall and the Relentless Dissent to Death as a Punishment, 22 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 591 (1995) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol22/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW ADHERING TO OUR VIEWS: BRENNAN AND MARSHALL AND THE RELENTLESS DISSENT TO DEATH AS A PUNISHMENT Michael Mello VOLUME 22 WINTER 1995 NUMBER 3 Recommended citation: Michael Mello, Adhering to Our Views: Brennan and Marshall and the Relentless Dissent to Death as a Punishment, 22 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 591 (1995). ADHERING TO OUR VIEWS: JUSTICES BRENNAN AND MARSHALL AND THE RELENTLESS DISSENT TO DEATH AS A PUNISHMENT MICHAEL MELLO* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 592 A. Capital Punishmentand the Modern Court: An Overview ..................................................... 593 B. The Evolving Law of Death: "The Supreme Court's Obstacle Course" .............................. 598 II. LEGITIMACY IN HISTORY ......................................... 606 A. The Supreme Court: "Nine Scorpions in a Bottle" .................... .................................. 606 B. Early History of Dissent ................................. 607 1. Seriatim Opinions..................................... 607 2. Early "Opinions of the Court"--andEarly Dissents ................................................ -

Abington School District V. Schempp 1 Ableman V. Booth 1 Abortion 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 Bill of Rights 66 Birth Control and Contraception 71 Abington School District v. Schempp 1 Hugo L. Black 73 Ableman v. Booth 1 Harry A. Blackmun 75 Abortion 2 John Blair, Jr. 77 Adamson v. California 8 Samuel Blatchford 78 Adarand Constructors v. Peña 8 Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell 79 Adkins v. Children’s Hospital 10 Bob Jones University v. United States 80 Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl 13 Boerne v. Flores 81 Advisory Opinions 15 Bolling v. Sharpe 81 Affirmative Action 15 Bond v. United States 82 Afroyim v. Rusk 21 Boumediene v. Bush 83 Age Discrimination 22 Bowers v. Hardwick 84 Samuel A. Alito, Jr. 24 Boyd v. United States 86 Allgeyer v. Louisiana 26 Boy Scouts of America v. Dale 86 Americans with Disabilities Act 27 Joseph P. Bradley 87 Antitrust Law 29 Bradwell v. Illinois 89 Appellate Jurisdiction 33 Louis D. Brandeis 90 Argersinger v. Hamlin 36 Brandenburg v. Ohio 92 Arizona v. United States 36 William J. Brennan, Jr. 92 Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing David J. Brewer 96 Development Corporation 37 Stephen G. Breyer 97 Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition 38 Briefs 99 Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority 38 Bronson v. Kinzie 101 Assembly and Association, Freedom of 39 Henry B. Brown 101 Arizona v. Gant 42 Brown v. Board of Education 102 Atkins v. Virginia 43 Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association 104 Automobile Searches 45 Brown v. Maryland 106 Brown v. Mississippi 106 Bad Tendency Test 46 Brushaber v. Union Pacific Railroad Company 107 Bail 47 Buchanan v. -

Chapter 2 the Marshall Court and the Early Republic

Chapter 2 The Marshall Court and the Early Republic I. The Supreme Court in Its Initial Years: 1 78918O11 The Supreme Court of the United States was a relatively insignificant institution during the first decade of the new Republic. Presidents Washington and Adams had some difficulty attracting people to serve, and the rate of turnover was high. Three men were appointed chiefjustice during the first 12 years.JohnJay resigned after six years to serve as New York’s governor, which he presumably deemed the more important office (and during his tenure he sailed to England to serve as the princi pal negotiator of what became known as the Jay Treaty with Great Britain, which, together with his co-authorship of the Federalist Papers, remains his primary claim to fame for most historians) . His successor, John Rutledge, had been appointed as an Associate in 1 789 but had resigned in 1 791 , without ever sitting, to go to the more prestigious South Carolina Supreme Court. He was nominated to become Chief Justice ofthe U.S. Supreme Court in 1795 but failed to receive Senate confirmation. Thereafter, Oliver Ellsworth was nominated and confirmed in 1796; he served until 1800, when he resigned while overseas on a diplomatic mission to France. One source of discontent was the onerous duty of “riding circuit,” which required eachJustice to travel twice a year to sit in the federal circuit court districts. (There were no “circuit courts” in the modern sense; instead, they consisted of districtjudges sitting together with a Supreme Courtjustice as a “circuit court.”) The trips were strenuous and time-consuming. -

Supreme Court Justices

The Supreme Court Justices Supreme Court Justices *asterick denotes chief justice John Jay* (1789-95) Robert C. Grier (1846-70) John Rutledge* (1790-91; 1795) Benjamin R. Curtis (1851-57) William Cushing (1790-1810) John A. Campbell (1853-61) James Wilson (1789-98) Nathan Clifford (1858-81) John Blair, Jr. (1790-96) Noah Haynes Swayne (1862-81) James Iredell (1790-99) Samuel F. Miller (1862-90) Thomas Johnson (1792-93) David Davis (1862-77) William Paterson (1793-1806) Stephen J. Field (1863-97) Samuel Chase (1796-1811) Salmon P. Chase* (1864-73) Olliver Ellsworth* (1796-1800) William Strong (1870-80) ___________________ ___________________ Bushrod Washington (1799-1829) Joseph P. Bradley (1870-92) Alfred Moore (1800-1804) Ward Hunt (1873-82) John Marshall* (1801-35) Morrison R. Waite* (1874-88) William Johnson (1804-34) John M. Harlan (1877-1911) Henry B. Livingston (1807-23) William B. Woods (1881-87) Thomas Todd (1807-26) Stanley Matthews (1881-89) Gabriel Duvall (1811-35) Horace Gray (1882-1902) Joseph Story (1812-45) Samuel Blatchford (1882-93) Smith Thompson (1823-43) Lucius Q.C. Lamar (1883-93) Robert Trimble (1826-28) Melville W. Fuller* (1888-1910) ___________________ ___________________ John McLean (1830-61) David J. Brewer (1890-1910) Henry Baldwin (1830-44) Henry B. Brown (1891-1906) James Moore Wayne (1835-67) George Shiras, Jr. (1892-1903) Roger B. Taney* (1836-64) Howell E. Jackson (1893-95) Philip P. Barbour (1836-41) Edward D. White* (1894-1921) John Catron (1837-65) Rufus W. Peckham (1896-1909) John McKinley (1838-52) Joseph McKenna (1898-1925) Peter Vivian Daniel (1842-60) Oliver W. -

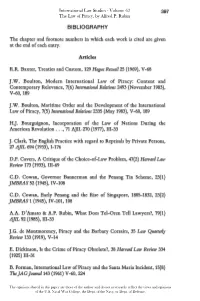

BIBLIOGRAPHY the Chapter and Footnote Numbers in Which Each

397 BIBLIOGRAPHY The chapter and footnote numbers in which each work is cited are given at the end of each entry. Articles R.R. Baxter, Treaties and Custom, 129 Hague Recueil25 (1969), V-68 J.W. Boulton, Modern International Law of Piracy: Content and Contemporary Relevance, 7(6) International Relations 2493 (November 1983), V-60, 189 J.W. Boulton, Maritime Order and the Development of the International Law of Piracy, 7(5) International Relations 2335 (May 1983), V-60, 189 H.J. Bourguignon, Incorporation of the Law of Nations During the American Revolution ..., 71 AJIL 270 (1977), III-33 J. Clark, The English Practice with regard to Reprisals by Private Persons, 27 AJIL 694 (1933), 1-176 D.F. Cavers, A Critique of the Choice-of-Law Problem, 47(2) Harvard Law Review 173 (1933), III-69 C.D. Cowan, Governor Bannerman and the Penang Tin Scheme, 23(1) JMBRAS 52 (1945), IV-l08 C.D. Cowan, Early Penang and the Rise of Singapore, 1805-1832, 23(2) JMBRAS 1 (1945), IV-l0l, 108 A.A. D'Amato & A.P. Rubin, What Does Tel-Oren Tell Lawyers?, 79(1) AJIL 92 (1985), III-33 J.G. de Montmorency, Piracy and the Barbary Corsairs, 35 Law Quarterly Review 133 (1919), V-14 E. Dickinson, Is the Crime of Piracy Obsolete?, 38 Harvard Law Review 334 (1925) III-31 B. Forman, International Law of Piracy and the Santa Maria Incident, 15(8) TheJAG Journal 143 (1961) V-60, 224 398 Bibliography L. Gross, Some Observations on the Draft Code ofOffense Against the Peace and Security of Mankind, 13 Israel Yearbook on Human Rights 9 (1983) V-235 L. -

The Marshall Court and Property Rights: a Reappraisal, 33 J

UIC Law Review Volume 33 Issue 4 Article 14 Summer 2000 The Marshall Court and Property Rights: A Reappraisal, 33 J. Marshall L. Rev. 1023 (2000) James W. Ely Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Contracts Commons, Courts Commons, Judges Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation James W. Ely Jr., The Marshall Court and Property Rights: A Reappraisal, 33 J. Marshall L. Rev. 1023 (2000) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol33/iss4/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MARSHALL COURT AND PROPERTY RIGHTS: A REAPPRAISAL JAMES W. ELY, JR.* INTRODUCTION Historians have long stressed the affinity between the jurisprudence of John Marshall and the protection of property rights. "Two fixed conceptions which dominated Marshall during his long career on the bench," Vernon L. Parrington observed, "were the sovereignty of the federal state and the sanctity of private property."1 Famous cases involving property rights and contractual stability figured prominently in the work of the Marshall Court. The property-conscious tenets of Marshall's constitutionalism helped lay the legal foundation for a market economy and had a lasting impact on the American polity. Beginning with the Progressive movement, and continuing through the New Deal Era, the rights of property owners were often disparaged as impediments to economic regulation and the welfare state. -

The Full Story of United States V. Smith, Americaâ•Žs Most Important

Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 1 Issue 2 November 2012 The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case Joel H. Samuels Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Political Science Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Rule of Law Commons, Social History Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Joel H. Samuels, The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case, 1 PENN. ST. J.L. & INT'L AFF. 320 (2012). Available at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol1/iss2/7 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2012 VOLUME 1 NO. 2 THE FULL STORY OF UNITED STATES V. SMITH, AMERICA’S MOST IMPORTANT PIRACY CASE Joel H. Samuels* INTRODUCTION Many readers would be surprised to learn that a little- explored nineteenth-century piracy case continues to spawn core arguments in modern-day civil cases for damages ranging from environmental degradation in Latin America to apartheid-era investment in South Africa, as well as criminal trials of foreign terrorists.1 That case, United States v. Smith,2 decided by the United * Associate Professor, Deputy Director, Rule of Law Collaborative, University of South Carolina School of Law. -

The Full Story of U.S. V. Smith, America's Most Important Piracy Case

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Law School 2012 The ulF l Story of U.S. v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case Joel H. Samuels University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/law_facpub Part of the International Law Commons, Rule of Law Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons Recommended Citation Joel H. Samuels, The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case, 1 Penn. St. J.L. & Int'l Aff. 320 (2012). This Article is brought to you by the Law School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 1 | Issue 2 November 2012 The ulF l Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case Joel H. Samuels ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Joel H. Samuels, The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case, 1 Penn. St. J.L. & Int'l Aff. 320 (2012). Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol1/iss2/7 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2012 VOLUME 1 NO. 2 THE FULL STORY OF UNITED STATES V. SMITH, AMERICA’S MOST IMPORTANT PIRACY CASE Joel H. Samuels* INTRODUCTION Many readers would be surprised to learn that a little- explored nineteenth-century piracy case continues to spawn core arguments in modern-day civil cases for damages ranging from environmental degradation in Latin America to apartheid-era investment in South Africa, as well as criminal trials of foreign terrorists.1 That case, United States v. -

John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court'

H-Law Huebner on Newmyer, 'John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court' Review published on Friday, March 1, 2002 R. Kent Newmyer. John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001. xviii + 511 pp. $39.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8071-2701-8. Reviewed by Tim Huebner (Department of History, Rhodes College) Published on H-Law (March, 2002) R. Kent Newmyer and the Heroic Age of Judicial Biography? R. Kent Newmyer and the Heroic Age of Judicial Biography? If he had not already done so, with the publication of this brilliant study of the life and work of John Marshall, R. Kent Newmyer has surely established himself as the foremost judicial biographer of our day. Previously known for his definitive work on Justice Joseph Story, Newmyer takes on an even more difficult subject in the "great chief justice." Skeptical readers may wonder--as Newmyer probably did when he began this project--what more could possibly be said about the man whom John Adams appointed as the fourth chief justice of the United States. Marshall and the Court over which he presided have, after all, been the subject of scores of scholarly books, articles, and dissertations, as well as a number of poplar biographies and essays. This book will pleasantly surprise such skeptics. From the first page to the last, Newmyer offers a compelling examination of Marshall that includes just the right blend of narrative, synthesis, and analysis. Newmyer builds on the work of other historians at the same time that he offers fresh insights.