Pride Or Shame? Assessing LGBTI Asylum Applications in the Netherlands After the Judgments XYZ And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Out in Office

OUT IN OFFICE LGBT Legislators and LGBT Rights Around the World OUT TO WIN Andrew Reynolds Acknowledgments Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Netherlands, Netherlands Antilles, Northern Ireland, Sierra Leone, South Africa, I am indebted to research assistance at the University Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Yemen, and Zimbabwe. He has of North Carolina at Chapel Hill provided by Alissandra received research awards from the U.S. Institute Stoyan, Elizabeth Menninga, Ali Yanus, Alison Evarts, of Peace, the National Science Foundation, the US Mary Koenig, Allison Garren, Olivia Burchett, and Agency for International Development, and the Ford Desiree Smith. Comments and advice were gratefully Foundation. Among his books are Designing Democracy received from Layna Mosley, George Walker, John in a Dangerous World (Oxford, 2011), The Architecture Sweet, Arnold Fleischmann, Gary Mucciaroni, Holning of Democracy: Constitutional Design, Conflict Lau, and Stephen Gent. Management, and Democracy (Oxford, 2002), Electoral Graphic design by UNC Marketing and Design with Systems and Democratization in Southern Africa thanks to Megan M. Johnson and Chelsea Woerner. (Oxford, 1999), Election 99 South Africa: From Mandela Monica Byrne did a wonderful job of editing the text. to Mbeki (St. Martin’s, 1999), and Elections and Conflict Management in Africa (USIP, 1998), co-edited with T. Sisk. His forthcoming book Modest Harvest: Legacies Andrew Reynolds and Limits of the Arab Spring (co-authored with Jason Andrew Reynolds is an Associate Professor of Political Brownlee [UT Austin] and Tarek Masoud [Harvard]) Science at UNC Chapel Hill and the Chair of Global will be published by Oxford. In 2012 he embarked on a Studies. He received his M.A. -

Tijdschrift Van Het Kenniscentrum

JAARGANG 26 • NUMMER 4 SEPTEMBER 2005 0·· I ? ~ TIJDSCHRIFT VAN HET KENNISCENTRUM THEMA IDEE SEPTEMBER 2005 OP WEG NA DE BRIEF VAN BORIS 3 De kortste weg naar nieuwe solidariteit, inleiding op het thema DOOR KEES VERHAAR EN MARIANNE WILSCHUT 4 Heeft Boris nog oog voor de toekomst? - DOOR CONSTANTUN DOLMANS 7 Solidair zonder centen - DOOR SjlERA DE VRIES 8 Democratiseren is een werkwoord - DOOR WUBRAND VAN SCHUUR 9 D66 moet zijn sociale kant tonen - ·DOOR SjAAK SCHEELE 10 Watskeburt met Boris? - DOOR LOUISE VAN ZETTEN 12 Het echte vernieuwingselan is er uit - DOOR RON VAN DOOTINGH 13 Nieuwe tijd vraagt om nieuw D66 - DOOR MENNO VAN DER LAND 1 5 Een realistisch modern mensbeeld - DOOR CR. VAN DER WOUDEN 17 Investeren leidt tot minder recidiveren - DOOR FRED BASTEMEUER 20 Snoeien in aantal provincies lost hun problemen niet op - DOOR KLAARTjE PETERS 22 Mens sana in corpore sane - DOOR KEES VERHAAR 23 Canada als model voor integratie in Nederland DOOR HUIGH VAN DER MAN DELE EN TjAK REAWARUW 24 Paspoort niet meer dan een gebruiksvoorwerp - DOOR WOUTER-JAN OOSTEN 26 Uitstroom van breinen hoeft geen probleem te zijn DOOR CHANTALjANSEN EN ELISABETH OPPENHUIS DEjONG 29 De 0 in het buitenlands beleid van D66 - DOOR MARIEKE VAN DOORN 31 Kinderopvang: niet arbeidsmarktdenken maar kind centraal DOOR MARTIN VAN'T ZET 34 laat scholen het niet alleen opknappen - DOORjOHN BUL 35 Heeft democratie nog wel toekomst? - DOOR SOPHIE MOLEMA 36 Vertrouwen en integriteit - DOOR LENY ZOMER 36 De kloof tussen burger en politiek - DOOR KEES VAN LOON 37 Haal meer -

Brief of Human Rights Watch and the New York City Bar Association, Et Al.,* As Amici Curiae Supporting Petitioners

Nos. 14-556, 14-562, 14-571 & 14-574 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States JAMES OBERGEFELL, et al., Petitioners, v. RICHARD HODGES, Director, Ohio Department of Health, et al., Respondents. On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit BRIEF OF HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH AND THE NEW YORK CITY BAR ASSOCIATION, ET AL.,* AS AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING PETITIONERS James D. Ross Richard L. Levine Legal & Policy Director Counsel of Record HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Jay Minga‡ 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor WEIL, GOTSHAL & MANGES LLP New York, NY 10118 767 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10153 Anna M. Pohl Telephone: (212) 310-8286 Chair, Committee on [email protected] Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual ‡Only Admitted in California and Transgender Rights Marie-Claude Jean-Baptiste Robert T. Vlasis III Programs Director, WEIL, GOTSHAL & MANGES LLP Cyrus R. Vance Center for 1300 Eye Street, N.W., Ste. 900 International Justice Washington, DC 20005 NEW YORK CITY BAR Telephone: (202) 682-7024 ASSOCIATION [email protected] 42 West 44th Street New York, NY 10036 Counsel for Amici Curiae * See Appendix for a complete list of amici. i TABLE OF CONTENTS INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ............................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................... 5 ARGUMENT ............................................................ 15 I. COUNTRIES THAT HAVE LEGALIZED SAME-SEX MARRIAGE FACED AND REJECTED ARGUMENTS SIMILAR TO THOSE ADVANCED HERE ................................. 15 A. The Supposed Need to Regulate Procreation Is an Irrational Basis to Deny Same-Sex Marriage .............. 15 B. Animus Toward LGBT People Justifies Judicial Intervention ........... 20 C. LGBT People Are a Suspect Class .................................................... 24 D. -

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2. Malik Ben Achour, PS, Belgium 3. Tina Acketoft, Liberal Party, Sweden 4. Senator Fatima Ahallouch, PS, Belgium 5. Lord Nazir Ahmed, Non-affiliated, United Kingdom 6. Senator Alberto Airola, M5S, Italy 7. Hussein al-Taee, Social Democratic Party, Finland 8. Éric Alauzet, La République en Marche, France 9. Patricia Blanquer Alcaraz, Socialist Party, Spain 10. Lord John Alderdice, Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom 11. Felipe Jesús Sicilia Alférez, Socialist Party, Spain 12. Senator Alessandro Alfieri, PD, Italy 13. François Alfonsi, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (France) 14. Amira Mohamed Ali, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Group, Die Linke, Germany 15. Rushanara Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 16. Tahir Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 17. Mahir Alkaya, Spokesperson for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Socialist Party, the Netherlands 18. Senator Josefina Bueno Alonso, Socialist Party, Spain 19. Lord David Alton of Liverpool, Crossbench, United Kingdom 20. Patxi López Álvarez, Socialist Party, Spain 21. Nacho Sánchez Amor, S&D, European Parliament (Spain) 22. Luise Amtsberg, Green Party, Germany 23. Senator Bert Anciaux, sp.a, Belgium 24. Rt Hon Michael Ancram, the Marquess of Lothian, Former Chairman of the Conservative Party, Conservative Party, United Kingdom 25. Karin Andersen, Socialist Left Party, Norway 26. Kirsten Normann Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 27. Theresa Berg Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 28. Rasmus Andresen, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (Germany) 29. Lord David Anderson of Ipswich QC, Crossbench, United Kingdom 30. Barry Andrews, Renew Europe, European Parliament (Ireland) 31. Chris Andrews, Sinn Féin, Ireland 32. Eric Andrieu, S&D, European Parliament (France) 33. -

Lettre Conjointe De 1.080 Parlementaires De 25 Pays Européens Aux Gouvernements Et Dirigeants Européens Contre L'annexion De La Cisjordanie Par Israël

Lettre conjointe de 1.080 parlementaires de 25 pays européens aux gouvernements et dirigeants européens contre l'annexion de la Cisjordanie par Israël 23 juin 2020 Nous, parlementaires de toute l'Europe engagés en faveur d'un ordre mondial fonde ́ sur le droit international, partageons de vives inquietudeś concernant le plan du president́ Trump pour le conflit israeló -palestinien et la perspective d'une annexion israélienne du territoire de la Cisjordanie. Nous sommes profondement́ preoccuṕ eś par le preć edent́ que cela creerait́ pour les relations internationales en geń eral.́ Depuis des decennies,́ l'Europe promeut une solution juste au conflit israeló -palestinien sous la forme d'une solution a ̀ deux Etats,́ conformement́ au droit international et aux resolutionś pertinentes du Conseil de securit́ e ́ des Nations unies. Malheureusement, le plan du president́ Trump s'ecarté des parametres̀ et des principes convenus au niveau international. Il favorise un controlê israelień permanent sur un territoire palestinien fragmente,́ laissant les Palestiniens sans souverainete ́ et donnant feu vert a ̀ Israel̈ pour annexer unilateralement́ des parties importantes de la Cisjordanie. Suivant la voie du plan Trump, la coalition israelienné recemment́ composeé stipule que le gouvernement peut aller de l'avant avec l'annexion des̀ le 1er juillet 2020. Cette decisioń sera fatale aux perspectives de paix israeló -palestinienne et remettra en question les normes les plus fondamentales qui guident les relations internationales, y compris la Charte des Nations unies. Nous sommes profondement́ preoccuṕ eś par l'impact de l'annexion sur la vie des Israelienś et des Palestiniens ainsi que par son potentiel destabilisateuŕ dans la regioń aux portes de notre continent. -

Vrijheid En Veiligheid in Het Politieke Debat Omtrent Vrijheidbeperkende Wetgeving

Stagerapport Vrijheid en Veiligheid in het politieke debat omtrent vrijheidbeperkende wetgeving Jeske Weerheijm Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd in opdracht van Bits of Freedom, in het kader van een stage voor de masteropleiding Cultural History aan de Universiteit Utrecht. De stage is begeleid door Daphne van der Kroft van Bits of Freedom en Joris van Eijnatten van de Universiteit Utrecht. Dit werk is gelicenseerd onder een Creative Commons Naamsvermelding-NietCommercieel- GelijkDelen 4.0 Internationaal licentie. Bezoek http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ om een kopie te zien van de licentie of stuur een brief naar Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. INHOUDSOPGAVE 1. inleiding 1 1.1 vrijheidbeperkende wetgeving 1 1.2 veiligheid en vrijheid 3 1.3 een historische golfbeweging 4 1.4 argumenten 6 1.5 selectiecriteria wetten 7 1.6 bronnen en beperking 7 1.7 stemmingsoverzichten 8 1.8 structuur 8 2. algemene beschouwing 9 2.1 politieke partijen 9 2.2 tijdlijn 17 3. wetten 19 3.1 wet op de Inlichtingen- en veiligheidsdiensten 19 3.2 wet justitiële en strafvorderlijke gegevens 24 3.3 wet eu-rechtshulp – wet vorderen gegevens telecommunicatie 25 3.4 wet computercriminaliteit II 28 3.5 wet opsporing en vervolging terroristische misdrijven 32 3.6 wijziging telecommunicatiewet inzake instellen antenneregister 37 3.7 initiatiefvoorstel-waalkens verbod seks met dieren 39 3.8 wet politiegegevens 39 3.9 wet bewaarplicht telecommunicatiegegevens 44 4. conclusie 50 4.1 verschil tweede en eerste Kamer 50 4.2 politieke -

“We Need a Law for Liberation” RIGHTS Gender, Sexuality, and Human Rights in a Changing Turkey WATCH

Turkey HUMAN “We Need a Law for Liberation” RIGHTS Gender, Sexuality, and Human Rights in a Changing Turkey WATCH “We Need a Law for Liberation” Gender, Sexuality, and Human Rights in a Changing Turkey Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-316-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org May 2008 1-56432-316-1 “We Need a Law for Liberation” Gender, Sexuality, and Human Rights in a Changing Turkey Glossary of Key Terms........................................................................................................ 1 I. Summary...................................................................................................................... 3 Visibility and Violence .................................................................................................... 3 Key Recommendations ..................................................................................................10 Methods........................................................................................................................12 II. -

Historica 2020-03 Binnenwerk

/ Twintigste eeuw / De geschiedenis van een symbolisch strijdpunt Seksuele gerichtheid in artikel 1 van de Grondwet De juridische gelijkstelling van homoseksuelen in Nederland begon in 1971 met de afschaffing van het discriminerende artikel 248bis Sr.1 In 1994 werd na een lange strijd de Algemene wet gelijke behandeling (Awgb) aangenomen, inclu- sief (hetero- en) homoseksualiteit als non-discriminatiegrond.2 In 2001 volgde de openstelling van het huwelijk voor paren van hetzelfde geslacht. De juri- dische gelijkstelling van homoseksualiteit in Nederland leek daarmee voltooid. In het begin van deze eeuw kwam echter een volgende eis op: neem homo- seksualiteit of seksuele gerichtheid op in artikel 1 van de Grondwet dat nu stelt: Bron: Wolters Kluwer Wolters Bron: “Allen die zich in Nederland bevinden, worden in gelijke gevallen gelijk behandeld. Discriminatie wegens godsdienst, levensovertuiging, politieke gezindheid, ras, ge- slacht of op welke grond dan ook, is niet toegestaan.” (Art. 1 Gw) / Joke Swiebel / geving. “De rechter treedt niet in de beoordeling van de grondwettigheid van wetten en verdragen” (art. 120 Gw). Het oordeel over de mate waarin voorgestelde wetten in In deze bijdrage ga ik na hoe deze kwestie op de politieke overeenstemming zijn met de Grondwet komt alleen de wet- agenda is gekomen en hoe die discussie is verlopen. Wat zou gever toe. Deze stand van zaken is niet ideaal. Een aantal ju- Iopname van homoseksualiteit of seksuele gerichtheid in arti- risten en politici heeft gepleit voor afschaffing van dit toet- kel 1 Grondwet opleveren bezien vanuit het gezichtspunt van singsverbod. Bescherming van de rechten en belangen van de homobeweging?3 Was de juridische gelijkstelling niet al de burger moet boven het primaat van de wetgever gaan, voltooid? Waarom werd deze kwestie eerst na 2001 een cen- vinden zij. -

Personalization of Political Newspaper Coverage: a Longitudinal Study in the Dutch Context Since 1950

Personalization of political newspaper coverage: a longitudinal study in the Dutch context since 1950 Ellis Aizenberg, Wouter van Atteveldt, Chantal van Son, Franz-Xaver Geiger VU University, Amsterdam This study analyses whether personalization in Dutch political newspaper coverage has increased since 1950. In spite of the assumption that personalization increased over time in The Netherlands, earlier studies on this phenomenon in the Dutch context led to a scattered image. Through automatic and manual content analyses and regression analyses this study shows that personalization did increase in The Netherlands during the last century, the changes toward that increase however, occurred earlier on than expected at first. This study also shows that the focus of reporting on politics is increasingly put on the politician as an individual, the coverage in which these politicians are mentioned however became more substantive and politically relevant. Keywords: Personalization, content analysis, political news coverage, individualization, privatization Introduction When personalization occurs a focus is put on politicians and party leaders as individuals. The context of the news coverage in which they are mentioned becomes more private as their love lives, upbringing, hobbies and characteristics of personal nature seem increasingly thoroughly discussed. An article published in 1984 in the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf forms a good example here, where a horse race betting event, which is attended by several ministers accompanied by their wives and girlfriends is carefully discussed1. Nowadays personalization is a much-discussed phenomenon in the field of political communication. It can simply be seen as: ‘a process in which the political weight of the individual actor in the political process increases 1 Ererondje (17 juli 1984). -

Biographies Guests and Speakers

Biographies Guests and Speakers Boris Dittrich Boris Dittrich leads Human Rights Watch's advocacy efforts on the rights of LGBT people around the world. He meets regularly with victims of homophobia and trans-phobia, and with government officials, members of parliament, and journalists in Africa, Latin America, Asia and Europe to push for progress on issues of sexual orientation and gender identity. For more information see: https://www.hrw.org/about/people/boris-dittrich Marieke Brouwer Drs. Marieke Brouwer ( 1958) studied theology at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and psychology of religion at the Katholieke Universiteit in Nijmegen. She works as a minister of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Amsterdam since 1991. She is also a spiritual director and directs the Huis op het Spui, the spiritual centre of the Lutheran Church in Amsterdam. Kees Waaldijk is professor of comparative sexual orientation law at Leiden Law School in the Netherlands. He has published widely on the process of legal recognition of same-sex orientation in different countries. His inaugural lecture was about The Right to Relate, which like most of his publications is online available at www.law.leidenuniv.nl/waaldijk. He is currently developing a Global Index on Legal Recognition of Homosexual Orientation, also presented on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JPwrJ9t0Zi4). Eric Gitari is founder and executive director of the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, Kenya (www.nglhrc.com). He studied Law at the University of Nairobi. He has challenged the government’s refusal to register NGLHRC in the Kenyan High Court in Eric Gitari vs NGO Board (http://kenyalaw.org/caselaw/cases/view/108412/) and won in a groundbreaking judgment in April 2015 where judges said sexual orientation is protected in the Kenyan Constitution. -

Summer School “Sexual Orientation & Gender Identity in International Law

Summer School “Sexual Orientation & Gender Identity in International Law: Human Rights and Beyond” The Hague & Amsterdam, Wednesday 24 July – Friday 2 August 2019 draft programme, version 8 July 2019, subject to changes and additions Wednesday 24 July 2019 August (in The Hague) 12.45 – 13.15 Registration 13.30 – 14.45 The global picture and how it is moving Kees Waaldijk, professor of Comparative Sexual Orientation Law – Leiden University 15.00 – 16.30 Poster presentations about country situations By all participants 16.45 – 18.00 The right to relate – as reflected in sexual orientation cases at the UN Human Rights Committee Kees Waaldijk, professor of Comparative Sexual Orientation Law – Leiden University 19.00 – 21:00 Opening dinner Thursday 25 July 2019 (in The Hague) 10.30 – 11.45 Transgender issues across the world Alecs Recher, Transgender Network Switzerland 12.00 – 13.00 Gender identity in the case law of the European Court of Human Rights Alecs Recher, Transgender Network Switzerland 13.15 – 14.15 Lunch 14.30 – 15.45 Sexual and gender minorities in international refugee law Katinka Ridderbos, Senior Research and Information Officer in the Division of International Protection at the UN Refugee agency, UNHCR 16.00 – 17.30 Discussion on the position of refugees of diverse SOGIESC Katinka Ridderbos, Senior Research and Information Officer in the Division of International Protection at the UN Refugee agency, UNHCR, with guests: Berachard Njankou (law graduate, D.E.A., University of Douala Cameroon), The Hague & Moses Walusimbi, founder -

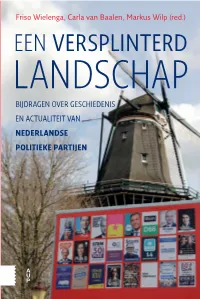

Een Versplinterd Landschap Belicht Deze Historische Lijn Voor Alle Politieke NEDERLANDSE Partijen Die in 2017 in De Tweede Kamer Zijn Gekozen

Markus Wilp (red.) Wilp Markus Wielenga, CarlaFriso vanBaalen, Friso Wielenga, Carla van Baalen, Markus Wilp (red.) Het Nederlandse politieke landschap werd van oudsher gedomineerd door drie stromingen: christendemocraten, liberalen en sociaaldemocraten. Lange tijd toonden verkiezingsuitslagen een hoge mate van continuïteit. Daar kwam aan het eind van de jaren zestig van de 20e eeuw verandering in. Vanaf 1994 zette deze ontwikkeling door en sindsdien laten verkiezingen EEN VERSPLINTERD steeds grote verschuivingen zien. Met de opkomst van populistische stromingen, vanaf 2002, is bovendien het politieke landschap ingrijpend veranderd. De snelle veranderingen in het partijenspectrum zorgen voor een over belichting van de verschillen tussen ‘toen’ en ‘nu’. Bij oppervlakkige beschouwing staat de instabiliteit van vandaag tegenover de gestolde LANDSCHAP onbeweeglijkheid van het verleden. Een dergelijk beeld is echter een ver simpeling, want ook in vroeger jaren konden de politieke spanningen BIJDRAGEN OVER GESCHIEDENIS hoog oplopen en kwamen kabinetten regelmatig voortijdig ten val. Er is EEN niet alleen sprake van discontinuïteit, maar ook wel degelijk van een doorgaande lijn. EN ACTUALITEIT VAN VERSPLINTERD VERSPLINTERD Een versplinterd landschap belicht deze historische lijn voor alle politieke NEDERLANDSE partijen die in 2017 in de Tweede Kamer zijn gekozen. De oudste daarvan bestaat al bijna honderd jaar (SGP), de jongste partijen (DENK en FvD) zijn POLITIEKE PARTIJEN nagelnieuw. Vrijwel alle bijdragen zijn geschreven door vertegenwoordigers van de wetenschappelijke bureaus van de partijen, waardoor een unieke invalshoek is ontstaan: wetenschappelijke distantie gecombineerd met een beschouwing van ‘binnenuit’. Prof. dr. Friso Wielenga is hoogleraardirecteur van het Zentrum für NiederlandeStudien aan de Westfälische Wilhelms Universität in Münster. LANDSCHAP Prof.