From Law to Content in the New Media Marketplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeff Greenfield

Jeff Greenfield Political Analyst One of America’s most respected political analysts, Jeff Greenfield has spent more than 30 years on network television, including CNN, ABC News, CBS, and as an anchor on PBS’ Need to Know. A five-time Emmy Award-winner, he is known for his quick wit and savvy insight into politics, history, the media and current events. Twice he was named to TV Guide‘s All-Star News “Dream Team” as best political commentator and was cited by the Washington Journalism Review as “the best in the business” for his media analysis. Greenfield has served as anchor booth analyst or floor reporter for every national political convention since 1988 and reported on virtually every important domestic political story in recent decades. He looks at American political history "through a fictional looking glass" in his national bestseller, Then Everything Changed: Stunning Alternate Histories of American Politics -- JFK, RFK, Carter, Ford, Reagan, released to great acclaim in March 2011. The New York Times called it "shrewdly written, often riveting." A follow-up e-book, 43*: When Gore Beat Bush—A Political Fable, was published in September 2012, and his latest, If Kennedy Lived: The First and Second Terms of President John F. Kennedy: An Alternate History, was released in October 2013. A former speechwriter for Robert F. Kennedy, Greenfield has authored or co-authored 12 books including national bestselling novel The People’s Choice, The Real Campaign, and Oh, Waiter! One Order of Crow!, an insider account of the contested 2000 presidential election. From 1998-2007 Greenfield was a senior analyst for CNN, serving as lead analyst for its coverage of the primaries, conventions, presidential debates and election nights. -

Media in the Lives of 8-18 Year-Olds, The

March 9, 2005 9:30 a.m. Presentation: Key Findings from New Research on Children’s Media Use Vicky Rideout, vice president and director, Program for the Study of Entertainment Media and Health, Kaiser Family Foundation 9:50 a.m. Roundtable Discussion Common, Grammy award winning Hip Hop artist Michael J. Copps, commissioner, Federal Communications Commission Jordan Levin, former CEO, The WB Television Network Donald Roberts, author, It’s Not Only Rock and Roll and professor of communication, Stanford University Juliet Schor, author, Born to Buy and professor of sociology, Boston College Alain Tascan, vice president and general manager, Electronic Arts Montreal Moderator: Jeff Greenfield, senior political analyst, CNN 10:50 a.m. Remarks Drew Altman, Ph.D., president and CEO, Kaiser Family Foundation 11:00 a.m. Keynote Address The Honorable Hillary Rodham Clinton, United States Senator 11:30 a.m. Questions and Answers Speaker Biographies and Contact Information March 9, 2005 DREW ALTMAN, PH.D. President and CEO Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation 2400 Sand Hill Road Menlo Park, CA 94025 Phone: 650-854-9400 Drew Altman is President and Chief Executive Officer of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. One of the nation's largest private foundations devoted to health, the Foundation is a leading independent voice and source of research and information on health care in the United States. Since 1987, the Foundation has also operated a major program supporting efforts to develop a more equitable health system in South Africa. In 1991, Dr. Altman directed a complete overhaul of the Foundation’s mission and operating style, leading to the Foundation’s standing today as a leader in health policy and communications. -

For August 1, 2010, CBS

Page 1 26 of 1000 DOCUMENTS CBS News Transcripts August 1, 2010 Sunday SHOW: CBS EVENING NEWS, SUNDAY EDITION 6:00 PM EST For August 1, 2010, CBS BYLINE: Russ Mitchell, Don Teague, Sharyl Attkisson, Seth Doane, Elaine Quijano GUESTS: Richard Haass SECTION: NEWS; International LENGTH: 2451 words HIGHLIGHT: On day 104 of the Gulf oil spill, news that a key step to seal the well could begin Tuesday as evidence mounts that B.P. used too many chemical dispersants to clean up the Gulf. President Obama may not be welcome on the campaign trail this fall as Democratic candidates fight to win their seats. Worries of drug violence in Mexico could spill over the border to the U.S. as National Guard`s troops get set to beef up border security. RUSS MITCHELL, CBS NEWS ANCHOR: Tonight on day 104 of the Gulf oil spill, news that a key step to seal the well could begin Tuesday as evidence mounts that B.P. used too many chemical dispersants to clean up the Gulf. I`m Russ Mitchell. Also tonight, campaign concerns. Why President Obama may not be welcome on the campaign trail this fall as Democratic candidates fight to win their seats. Border patrol, worries of drug violence in Mexico could spill over the border to the U.S. as National Guard`s troops get set to beef up border security. And just married, an inside account of the wedding yesterday of Chelsea Clinton and Marc Mezvinsky. And good evening. It is shaping up to be a very important week in the Gulf oil spill. -

A Legacy Diminished: President Obama and the Courts

Br. J. Am. Leg. Studies 8 (Special Issue) (2019), DOI: 10.2478/bjals-2019-0008 A Legacy Diminished: President Obama and the Courts Clodagh Harrington* Alex Waddan** ABSTRACT A central concern for any U.S. presidential administration is its relationship with the federal judiciary. For an administration, this relationship is potentially legacy making or breaking in two ways. First, what is the imprint that the administration leaves on the judiciary? Will a president have the opportunities and institutional capacity to change the political balance of the federal judiciary? Second, how will the judicial branch respond when the administration’s policy plans are, as many inevitably will be, challenged in the court system? Will the administration’s policy preferences be preserved and its agenda advanced, or will court decisions stymie important initiatives and restrict that agenda? This paper examines these questions with regard to the Obama administration’s record. The Obama era saw new levels of diversity in terms of judicial nominees and the courts did sometimes uphold key aspects of the Obama administration’s program to the chagrin of conservative opponents. Yet, with the benefit of two years hindsight, the evidence suggests that the Obama administration’s legacy with regard to both the central questions addressed in the paper was a diminished one. The administration’s capacity to reorient the federal bench was thwarted by the legislative branch, notably obstruction in Senate, with the consequences of that frustration highlighted by the rapid actions taken by the Trump administration and Senate Republicans in 2017-18. Furthermore, on balance, the decisions made by the federal judiciary on matters of significant concern to the Obama White House weakened rather than strengthened the administration’s legacy. -

Third-Party and Independent Presidential Candidates: the Need for a Runoff Mechanism

THIRD-PARTY AND INDEPENDENT PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES: THE NEED FOR A RUNOFF MECHANISM Edward B. Foley* INTRODUCTION The 2016 presidential election has been like no other. However it ends up, it has been marked by the singularly dispiriting fact that the two major party nominees have the highest unfavorable ratings of any presidential candidates in history.1 This environment, one would think, would be particularly auspicious for a third-party or independent candidate, but the electoral system is structured in a way that is so disadvantageous to any candidate other than the two major-party nominees that a serious third-party or independent challenger has yet to materialize. To be sure, as of this writing, the Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson is polling significantly higher than any third-party or independent candidate since Ross Perot.2 Jill Stein, the Green Party candidate, is also hovering * Director, Election Law @ Moritz, and Charles W. Ebersold and Florence Whitcomb Ebersold Chair in Constitutional Law, the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law. A much different version of this paper was presented at an Ohio State Democracy Studies workshop. I very much appreciate the extensive and constructive feedback I received from participants there, as well as from Deborah Beim, Barry Burden, Bruce Cain, Frank Fukuyama, Bernie Grofman, Eitan Hersh, Alex Keyssar, Nick Stephanopoulos, Rob Richie, and Charles Stewart. This Article is part of a forum entitled Election Law and the Presidency held at Fordham University School of Law. 1. See, e.g., Philip Rucker, These ‘Walmart Moms’ Say They Feel ‘Nauseated’ by the Choice of Clinton or Trump, WASH. -

Whose Life Is It Anyway: a Proposal to Redistribute Some of the Economic Benefits of Cameras in the Courtroom from Broadcasters to Crime Victims

South Carolina Law Review Volume 49 Issue 1 Article 3 Fall 1997 Whose Life Is It Anyway: A Proposal to Redistribute Some of the Economic Benefits of Cameras in the Courtroom from Broadcasters to Crime Victims Stephen D. Easton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Easton, Stephen D. (1997) "Whose Life Is It Anyway: A Proposal to Redistribute Some of the Economic Benefits of Cameras in the Courtroom from Broadcasters to Crime Victims," South Carolina Law Review: Vol. 49 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr/vol49/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Easton: Whose Life Is It Anyway: A Proposal to Redistribute Some of the E SOUTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 49 FALL 1997 NUMBER 1 WHOSE LIFE Is IT ANYWAY?: A PROPOSAL TO REDISTRIBUTE SOME OF THE ECONOMIC BENEFITS OF CAMERAS IN THE COURTROOM FROM BROADCASTERS TO CRIME VICTIMS STEPHEN D. EASTON* I. INTRODUCTION ................................. 2 II. CAMERAS IN THE COURTROOM ....................... 7 A. Cameras in Courtrooms:A Brief HistoricalPerspective ...... 8 1. The Pre-Television Era ....................... 8 2. ABA Canon 35 ............................ 9 3. Three States Allow Cameras..................... 10 4. Estes v. Texas: The United States Supreme Court Speaks 11 5. The FloridaExperiment ..................... 12 6. Chandler v. Florida: The Supreme Court Speaks Again . 12 7. The Few Become the Many ................... -

Hannah Arendt and the Dark Public Sphere

Hannah Arendt and the Dark Public Sphere John LeJeune PhD, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Department of History and Political Science, Georgia Southwestern State University Address: Georgia Southwestern State University Drive, 800, Americus, GA 31709 E-mail: [email protected] Hannah Arendt once described “dark times” as characterized by “‘credibility gaps’ and ‘invis- ible government,’ by speech that does not disclose what is but sweeps it under the carpet, by exhortations, moral and otherwise, that, under the pretext of upholding old truths, degrade all truth to meaningless triviality.” This paper argues that as Western democracies experience conditions that echo Arendt’s twentieth century assessment — among these are the death of truth, the decline of civility, and the dearth of authenticity in the public sphere — Arendt’s work helps us better understand two sources of this modern crisis. First is the blurring of truth and opinion in contemporary political discourse; second is the blurring of the public and private realms made possible by the coercive intermediation of the social. An acute danger of these circumstances is the lure of demagogues and extreme ideologies when the words and deeds of the public realm — either because they are not believed, or because they have been reduced to mere image-making — increasingly lack meaning, integrity, and spontaneity. A second danger is the erosion of faith in the free press (and with it our common world and basic facts) when the press itself, reacting to its own sense of darkness, undermines its role of truthteller by assuming the role of political actor. In the end I suggest that underlying these several acute issues of democracy lies a more basic tension in the public sphere centered on an Arendtian notion of “freedom of opinion.” Keywords: Hannah Arendt, public sphere, free press, lying, fake news, social realm Election 2016: Crises of Democracy The 2016 election of Donald Trump as US President signaled to many a crisis of Ameri- can democracy. -

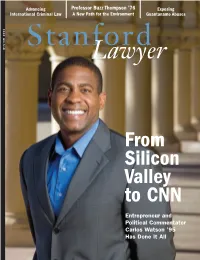

From Silicon Valley to CNN

Advancing Professor Buzz Thompson ’76 Exposing International Criminal Law A New Path for the Environment Guantanamo Abuses WINTER 2006 Stanford Lawyer From Silicon Valley to CNN Entrepreneur and Political Commentator Carlos Watson ’95 Has Done It All CONTENTS WINTER 2006 VOL. 40 NO. 2 COVER STORY BRIEFS 16 FROM SILICON 6 LAWYER OF THE YEAR VALLEY TO CNN Barbara Olshansky ’85, defender of Carlos Watson ’95 cofounded, U.S. detainees, wins award. led, and eventually sold a success- ful Silicon Valley startup. Now a 8 REMEMBERING FORMER DEAN regular contributor on CNN, he Longtime professor and former act- provides political commentary, ing dean John R. McDonough dies. writes a column, and occasionally hosts his own interview show. 9 NEW CLINICAL CENTER The law school celebrates the open- ing of its new Clinical Center. FEATURES 10 MILITARY PROTEST 13 ALUMNI WEEKEND Students and faculty demonstrate Under a beautiful blue sky, more when JAG recruiters visit campus. than 650 alumni, family, and friends gathered to renew friend- 11 HURRICANE RELIEF ships, hear stimulating panel The law school opens its doors to discussions, cheer on the football students from Tulane University. team, and celebrate an association with Stanford Law School. DISCOVERY 16 22 FORGING A NEW PATH FOR THE 30 SEEKING MORE GOODLY CREATURES ENVIRONMENT Professor Hank Greely explores the As codirector of the Stanford implications of genetic and repro- Institute for the Environment, ductive technologies that may allow law professor Buzz Thompson us to create “enhanced” children. JD/MBA ’76 (BA ’72) is bringing together lawyers, biologists, geo- 35 A CONVERSATION WITH PROFESSOR physicists, economists, and other JENNY S. -

The Effect of 24-Hour Television News on American Democracy and the Daily Show As a Counterbalance to 24-Hour News: a History

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2010 The Effect of 24-Hour Television News on American Democracy and The Daily Show as a Counterbalance to 24-Hour News: A History Thomas W. Queen College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Queen, Thomas W., "The Effect of 24-Hour Television News on American Democracy and The Daily Show as a Counterbalance to 24-Hour News: A History" (2010). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 669. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/669 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Effect of 24-Hour Television News on American Democracy & The Daily Show as a Counterbalance to 24-Hour News ◊ A History BY Thomas Queen Copyright © 2010 by Thomas Queen All rights reserved. ii Contents Acknowledgements iv Preface 1 ONE Media in America 4 TWO The Election that Went Awry 24 THREE The Longer than Expected War 57 FOUR De Tocqueville’s Reef 99 Notes 109 Bibliography 119 iii Acknowledgements To my parents, who in middle school let me stay up to watch The Daily Show; to my professors, who finally got me to avoid passive voice; to my friends, who heard more about this project than they probably cared but listened anyway: thank you. -

“Anchor Babies,” Immigration Reform, and the Constitution

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: Ashley Berke Alex McKechnie Director of Public Relations Public Relations Coordinator 215.409.6693 215.409.6895 [email protected] [email protected] “ANCHOR BABIES,” IMMIGRATION REFORM, AND THE CONSTITUTION: PANELISTS PUT THE 14 TH AMENDMENT TO THE TEST DURING THE PETER JENNINGS PROJECT AT THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER Philadelphia, PA (February 14, 2011) – The National Constitution Center will be Putting the 14 th Amendment to the Test with a conversation on the hotly debated issues of immigration reform and birthright citizenship on Saturday, March 5, 2011 at 5:30 p.m. The program is part of the Center’s 2011 Peter Jennings Project for Journalists and the Constitution . Admission is FREE, but reservations are required and can be made by calling 215.409.6700 or online at www.constitutioncenter.org . Jeff Greenfield , senior political correspondent for CBS News, will facilitate this highly interactive event, featuring Jennings Project fellows who will represent various stakeholders in the immigration debate. The event also will feature a panel of distinguished guests, including John Eastman , Donald P. Kennedy Chair in Law at Chapman University School of Law; State Representative Daryl Metcalfe (R-PA/12); Jorge Mursuli , president and CEO of Democracia Ahora; the Honorable Marjorie O. Rendell ; and Cecillia Wang , Managing Attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union’s Immigrants' Rights Project. The citizenship clause of the 14 th Amendment reads: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” This language recently has come under attack by -MORE- ADD ONE/14 TH AMENDMENT those who believe that, by giving birth to "anchor babies" who automatically have American citizenship, illegal immigrants are using the 14 th Amendment to gain a legal foothold in the U.S. -

1ROBERT F. KENNEDY, “STATEMENT on the DEATH of REVEREND MARTIN LUTHER KING, RALLY in INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA” (4 APRIL 1968) and ROBERT F

Voices of Democracy 11 (2016): 1-24 Drury and Crouch 1 1ROBERT F. KENNEDY, “STATEMENT ON THE DEATH OF REVEREND MARTIN LUTHER KING, RALLY IN INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA” (4 APRIL 1968) and ROBERT F. KENNEDY, “REMARKS AT THE CLEVELAND CITY CLUB” (5 APRIL 1968) Jeffrey P. Mehltretter Drury and Cole A. Crouch Wabash College Abstract: Following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Robert F. Kennedy delivered two speeches—a highly praised impromptu speech in Indianapolis and a less renowned exhortation in Cleveland—making sense of the death and condemning the tolerance and endless acts of violence in America. This essay analyzes Kennedy’s speeches as examples of prophetic rhetoric that accused the nation of sins and offered wisdom and justice as the path to redemption. Keywords: Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., Indianapolis, Cleveland, 1968 presidential election, prophetic rhetoric, ultimate terms, exhortation Robert F. Kennedy frequently ended his stump speeches during the 1968 presidential campaign by quoting George Bernard Shaw: “Some people see things as they are and say why? I dream things that never were and say, why not?” When Kennedy was assassinated in June of that year, his younger brother, Ted, immortalized this quotation by using it to conclude the eulogy of his late brother. It was a fitting tribute given Bobby’s focus on the future and his effort to, as indicated in the title of his 1967 book, “seek a newer world.”1And yet Kennedy waded deeply in the present world, confronting injustice, prejudice, poverty, and violence through a journey of self- and other-awareness. -

White Backlash in a Brown Country

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 50 Number 1 Fall 2015 pp.89-132 Fall 2015 White Backlash in a Brown Country Terry Smith DePaul University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Terry Smith, White Backlash in a Brown Country, 50 Val. U. L. Rev. 89 (2015). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol50/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Smith: White Backlash in a Brown Country Lecture WHITE BACKLASH IN A BROWN COUNTRY Terry Smith I would like to honestly say to you that the white backlash is merely a new name for an old phenomenon . It may well be that shouts of Black Power and riots in Watts and the Harlems and the other areas, are the consequences of the white backlash rather than the cause of them.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 90 II. PRIVILEGE AS ADDICTION, DEMOGRAPHY AS THREAT: EXPLAINING THE ETIOLOGY OF BACKLASH ........................................................................... 94 III. BACKLASH AND THE REVIVIFICATION OF CLASSICAL RACISM ............... 105 A. A Creeping “New White Nationalism?” .................................................. 106 B. The Othering of a President ...................................................................... 113 IV. WHITE BACKLASH AT THE BALLOT BOX: THE FIRE NEXT TIME ............ 117 A. From Inevitability to Backlash: Fallacies, Fears, and Suppression .......... 118 1. (Mis)Counting on Latinos ....................................................................