Merchant, P. (2018). Spectres of Hierarchy in a Chilean Domestic Archive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

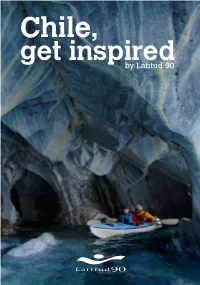

Latitud 90 Get Inspired.Pdf

Dear reader, To Latitud 90, travelling is a learning experience that transforms people; it is because of this that we developed this information guide about inspiring Chile, to give you the chance to encounter the places, people and traditions in most encompassing and comfortable way, while always maintaining care for the environment. Chile offers a lot do and this catalogue serves as a guide to inform you about exciting, adventurous, unique, cultural and entertaining activities to do around this beautiful country, to show the most diverse and unique Chile, its contrasts, the fascinating and it’s remoteness. Due to the fact that Chile is a country known for its long coastline of approximately 4300 km, there are some extremely varying climates, landscapes, cultures and natures to explore in the country and very different geographical parts of the country; North, Center, South, Patagonia and Islands. Furthermore, there is also Wine Routes all around the country, plus a small chapter about Chilean festivities. Moreover, you will find the most important general information about Chile, and tips for travellers to make your visit Please enjoy reading further and get inspired with this beautiful country… The Great North The far north of Chile shares the border with Peru and Bolivia, and it’s known for being the driest desert in the world. Covering an area of 181.300 square kilometers, the Atacama Desert enclose to the East by the main chain of the Andes Mountain, while to the west lies a secondary mountain range called Cordillera de la Costa, this is a natural wall between the central part of the continent and the Pacific Ocean; large Volcanoes dominate the landscape some of them have been inactive since many years while some still present volcanic activity. -

New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005-2015)

New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005-2015) Paul Rumney Merchant St John’s College August 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005 – 2015) Paul Rumney Merchant This thesis explores the potential of domestic space to act as the ground for new forms of community and sociability in Argentine and Chilean films from the early twenty-first century. It thus tracks a shift in the political treatment of the home in Southern Cone cinema, away from allegorical affirmations of the family, and towards a reflection on film’s ability to both delineate and disrupt lived spaces. In the works examined, the displacement of attention from human subjects to the material environment defamiliarises the domestic sphere and complicates its relation to the nation. The house thus does not act as ‘a body of images that give mankind proofs or illusions of stability’ (Bachelard), but rather as a medium through which identities are challenged and reformed. This anxiety about domestic space demands, I argue, a renewal of the deconstructive frameworks often deployed in studies of Latin American culture (Moreiras, Williams). The thesis turns to new materialist theories, among others, as a supplement to deconstructive thinking, and argues that theorisations of cinema’s political agency must be informed by social, economic and urban histories. The prominence of suburban settings moreover encourages a nuancing of the ontological links often invoked between cinema, the house, and the city. The first section of the thesis rethinks two concepts closely linked to the home: memory and modernity. -

Review / Reseña Complicit with Dictatorship and Complacent With

Vol. 16, Num. 1 (Fall 2018): 361-366 Review / Reseña Lazzara, Michael J. Civil Obedience: Complicity and Complacency in Chile since Pinochet. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2018. Complicit with Dictatorship and Complacent with its Legacy: Accomplices and Bystanders in Chile after Pinochet Audrey Hansen University of Michigan—Ann Arbor What responsibility do we have to the people around us when we narrate our own stories? How does making ourselves vulnerable to judgement for our prior actions affect our community? These are just a few of the important questions about accountability and community that Michael J. Lazzara considers in his book Civil Obedience: Complicity and Complacency in Chile since Pinochet. Going beyond an emphasis on the importance of restoring memory surrounding the human rights violations of General Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship (1973-1990), the works examined in this book shed light on the present-day impact of narratives by complicit and complacent subjects. Crucially, Lazzara argues that Chile’s protracted struggle to reckon with its violent past is exacerbated not only by the failure of civilian actors who were complicit with the regime to meaningfully account for their actions, but also by the complacency of Hansen 362 those who benefitted from the continuation of the dictatorship’s neoliberal economic model. Civil Obedience: Complicity and Complacency in Chile since Pinochet draws on a wide variety of mostly nonfiction primary texts to construct its argument, including biographies, autobiographies, films, and television interviews. Each chapter deals with one specific subject position, although Lazzara is careful to acknowledge that this is only a selection from the endless variety of subject positions possible on the spectrum of complicity. -

The Night of the Senses: Literary (Dis)Orders in Nocturno De Chile

Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies Travesia ISSN: 1356-9325 (Print) 1469-9575 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjla20 The night of the senses: literary (dis)orders in nocturno de chile Patrick Dove To cite this article: Patrick Dove (2009) The night of the senses: literary (dis)orders in nocturnodechile , Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies, 18:2-3, 141-154, DOI: 10.1080/13569320903361804 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13569320903361804 Published online: 02 Dec 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 486 View related articles Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cjla20 Patrick Dove THE NIGHT OF THE SENSES: LITERARY (DIS)ORDERS IN NOCTURNO DE CHILE En una noche oscura, con ansias en amores inflamada, (¡oh dichosa ventura!) salı´ sin ser notada, estando ya mi casa sosegada. San Juan de la Cruz, ‘La noche oscura’ Over the course of the last decade, and particularly in the wake of his untimely death at the age of fifty, the Chilean novelist Roberto Bolan˜o (1953–2003) has come to be viewed by critics and reviewers as perhaps the greatest Latin American writer of his generation and as a literary phenomenon rivaling the international impact of the Boom writers of the 1960s (Garcı´aMa´rquez, Fuentes, Vargas Llosa, Corta´zar).1 No doubt Bolan˜o’s reputation as a poe`te maudit – which has been cultivated through his own accounts of vagabondism and drug and alcohol abuse, together with his well-publicized and broadly aimed attacks on Latin American writers and literary institutions – has helped to bolster his critical reception outside the Spanish-speaking world, creating a somewhat ironic situation in which a figure renowned for his iconoclastic attitudes and positions emerges as an international representative of what we continue to call ‘Latin American literature’. -

Litical Leader and His Wife Were Seri

Dossier Said to Report Chile Hired Cuban lit Men () -,!:,....Dinges- the contents of the U.S. evidence. Townley also traveled to Borne in 0e- gaining, Townley's wife said In an in; Snectal to The Washineton Post Other sources confirmed that the law- tober 1975—at the time of an assassi- terview some time ago, is that his SANTIAGO, Chile—The dossier yer had first-hand knowledge of the nation attempt against Chilean exile family will be protected and that submitted by the United States to dossier. Bernardo Leighton, a leader of the op- Townley will not be required to tes- Chile on the assassination of Orlando The documents—about 700 pages of position Christian Democratic Party. ionthcoerntnhectiothnewithtetiejer Letelier reportedly contains charges testimony as well as films—are in- Leighton and his wife were both seri. ties ;Yi murder. that the Chilean secret police had a tended to prove the U.S. charges that ously wounded in the attack on a The source of much of the informs- relationship with Cuban Contreras and Espinoza, as DINA offi- BBoeorne street and she remains partially lion In the dossier about the Chilean- exile terrorists and sent some of them cers, ordered Townley and Fernandez paralzed. • Cuban connection is Rolando Otero, a as hit men on unsuccessful missions to carry out the Letelier assassination • Testimony by Townley that pilots Cuban exile and Bay of Pigs veteran to kill four other prominent Chilean with the Cubans' help. , with a long history of terrorist activi- and other employees of LAN Chile, exiles. Despite the secrecy rule, the U.S. -

Escrituras E Historias

Actas 14º Congreso Mundial de Semiótica: Trayectorias Buenos Aires Septiembre 2019 International Association for Semiotic Studies (IASS/AIS) Tomo 3 Escrituras e Historias Coordinadora Vanesa Pafundo Proceedings of the 14th World Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies (IASS/AIS) Actas 14º Congreso Mundial de Semiótica: Trayectorias Buenos Aires Septiembre 2019 International Association for Semiotic Studies (IASS/AIS) Tomo 3 Escrituras e historias Coordinadora Vanesa Pafundo Área Transdepartamental de Crítica de Artes Actas Buenos Aires. 14º Congreso Mundial de Semiótica : trayectorias : Proceedings of the 14th World Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies-IASS/AIS : tomo 3 : escrituras e historias / editado por Rolando Martínez Mendoza ; José Luis Petris ; prólogo de Vanesa Mara Pafundo. - 1a ed edición multilingüe. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Libros de Crítica. Área Transdepartamental de Crítica de Artes, 2020. Libro digital, PDF Edición multilingüe: Alemán ; Español ; Francés ; Inglés. Archivo Digital: descarga y online ISBN 978-987-47805-4-6 1. Semiología. 2. Semiótica. 3. Relatos. I. Martínez Mendoza, Rolando, ed. II. Petris, José Luis, ed. III. Pafundo, Vanesa Mara, prolog. IV. Título. CDD 401.41 Actas Buenos Aires. 14º Congreso Mundial de Semiótica: Trayectorias. Trajectories. Trajectoires. Flugbahnen. Asociación Argentina de Semiótica y Área Transdepartamental de Crítica de Artes de la Universidad Nacional de las Artes, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Proceedings of the 14th World Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies (IASS/AIS) Buenos Aires, 9 al 13 de septiembre de 2019. Tomo 3 ISSN 2414-6862 e-ISBN de la obra completa: 978-987-47805-0-8 e-ISBN del Tomo 3: 978-987-47805-4-6 DOI: 10.24308/IASS-2019-3 © IASS Publications & Libros de Crítica, noviembre 2020 Editores Generales José Luis Petris y Rolando Martínez Mendoza Editores Marina Locatelli y Julián Tonelli Diseño Andrea Moratti Todos los derechos reservados. -

The Street Art Culture of Chile and Its Power in Art Education

Culture-Language-Media Degree of Master of Arts in Upper Secondary Education 15 Credits; Advanced Level “We Really Are Not Artists, We Are Military. We Are Soldiers” The Street Art Culture of Chile and its Power in Art Education “Vi är inte konstnärer, vi är militärer. Vi är sodlater” Gatukonstkulturen i Chile och dess påverkan på bildundervisning Granlund, Magdalena Silén, Maria Master of Art in Secondary Education: 300 Credits. Examiner: Edström, Ann-Mari. Opposition Seminar: 31/05/2018. Supervisor: Mars, Annette. Foreword We would like to give a big thanks to all those whom have helped made this thesis possible: to all the people we have been interviewing and that have been showing us the streets of Santiago and Valparaiso. To Kajsa, Micke and Robbin for making sure we met the right people while conducting this study. To Annette Mars for all the guidance prior- and during the conducting of this thesis. To Mauricio Veliz Campos for all the support we were given during the minor field studies scholarship application, as well as during our time in Santiago. To Vinboxgruppis for your constant support during the last five years. And last but not least to SIDA, for the trust and financial support. Thank you! This thesis is written during the spring of 2018. We, the writers behind this thesis, have both come up with the purpose, research questions, method, interview guide, as well as been taking visual street notes together. 2 Abstract This thesis describes the street art culture of Chile and its power in art education. The thesis highlights the didactic questions what, how and why. -

1 El Museo Nacional De Bellas Artes De Santiago

UNIVERSUM • Vol. 31 • Nº 1 • 2016 • Universidad de Talca Te National Museum of Fine Arts of Santiago and its publications (1922-2009) Albert Ferrer Orts – Alberto Madrid Letelier Pp. 141 a 151 THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS OF SANTIAGO AND ITS PUBLICATIONS (1922-2009)1 El Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Santiago (Chile) a través de sus publicaciones: 1922-2009 Albert Ferrer Orts* Alberto Madrid Letelier** 1 Tis article forms part of the project “Ausencia de una política o política de la ausencia. Institucionalidad y desarrollo de las artes visuales en Chile 1849-1973” Fondecyt Nº 1140370, whose co-researcher is one of the authors of this publication. Tis paper was initially sent for review in Spanish, and it has been translated into English with the support of the Project FP150008, “Aumento y mejora del índice de impacto y de la internacionalización de la revista Universum por medio de la publicación de un mayor número de artículos en inglés.” Fund for publication of Scientifc Journals 2015, Scientifc Information Program, Scientifc and Technological Research National Commission (Conicyt), Chile. Este artículo fue enviado a revisión inicialmente en español y ha sido traducido al inglés gracias al Proyecto FP150008, “Aumento y mejora del índice de impacto y de la internacionalización de la revista Universum por medio de la publicación de un mayor número de artículos en inglés”. Fondo de Publicación de Revistas Científcas 2015, Programa de Información Científca, Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científca y Tecnológica (Conicyt), Chile. * Faculty of Art, Universidad de Playa Ancha de Ciencias de la Educación. Valparaíso, Chile. -

SYLLABUS GLOBAL OPPORTUNITIES CHILEAN CULTURE Universidad De Los Andes, Santiago, Chile January 2Nd – January 23Rd, 2019

SYLLABUS GLOBAL OPPORTUNITIES CHILEAN CULTURE Universidad de los Andes, Santiago, Chile January 2nd – January 23rd, 2019 COURSE: GO CHILEAN CULTURE PREREQUISITES: None CREDITS: EVALUATIONS: 2 week program: 3 US Credits / 6 ECTS Written paper and presentation about Credits chosen topic related to Chilean Culture. 3 week program: 4 US Credits / 8 ECTS Online Placement Test for Language Course. Credits Final Language Exam. TOTAL HOURS: ON CAMPUS LECTURES: CULTURAL AND ACADEMIC TRIPS AND 2 week program: 40 2 week program: 30 hours ACTIVITIES: hours 3 week program: 44 hours 2 week program: 15 hours 3 week program: 60 3 week program: 20 hours hours COURSE DESCRIPTION This course’s main objective is to give students a deep understanding of Chile’s culture through a sociological point of view from the Prehispanic Period, until today, and how it has evolved through the different migratory waves. Additionally, the course will present a general view of Chile’s current cultural scenario through different perspectives. Finally, this course includes a Language Unit, that can be either Spanish for non-Spanish speakers, or English for Spanish speakers. METHODOLOGY AND ACTIVITIES This course will include lectures by different UANDES professors and external lecturers, that will involve student interaction. Students will have to choose a topic related to Chilean Culture on which they will work through the duration of the program and will have to present it at the end of the course. They will be graded in accordance to the development of the paper, and the final presentation. Finally, the language course will include a final exam during the last week of the program. -

Embodied Absence Chilean Ar

Embodied Absence Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Carpenter Center Embodied Absence for the Visual Arts Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Oct 27, 2016–Jan 8, 2017 Works by Elías Adasme, Carmen This exhibition is co-organized Beuchat with Felipe Mujica and with DRCLAS as part of its research Johanna Unzueta, CADA (Colectivo project Conceptual Stumblings. Acciones de Arte), Francisco Copello, Exhibition and program support Luz Donoso, Juan Downey, Carlos is also provided by Harvard Leppe, Catalina Parra, Lotty University Committee on the Rosenfeld, UNAC (Unión por la Arts. The first iteration, Embodied Cultura), Cecilia Vicuña, and Raúl Absence: Ephemerality and Zurita with Cristóbal Lehyt Collectivity in Chilean Art of the 1970s (September 2015–January Guest curated by Liz Munsell, 2016), was organized by Museo Assistant Curator of Contemporary de la Solidaridad Salvador Art & Special Initiatives, Museum of Fine Allende, Santiago, Chile, with its Arts, Boston, and visiting curator, David substantial support in research Rockefeller Center for Latin American and production of works, in Studies (DRCLAS), Harvard University collaboration with DRCLAS. Embodied Absence Liz Munsell Following the U.S.-backed coup d’état in 1973,1 Chilean artists residing in Santiago and abroad created artworks that spoke to their experience of political, social, and geographic marginalization. Inside the country, they adopted the highly coded languages of conceptual art to evade censorship, exhibited work in public space in lieu of institutional support, and formed independently run galleries and artist collectives to protect their individual identities. Artists abroad staged public events and made artwork in solidarity with those at home. Their exhibitions, performances, interventions, and workshops spread awareness among international audiences and broke down isolating conditions within Chile. -

Caso Prats: La Conexión Con La Muerte De Frei Montalva

6 ◗ LUNES 7 DE FEBRERO DE 2005 País El juez Solís vuelve a Chile con un nombre que se Caso Prats:la conexión con G Diario Siete Archivo l juez Alejandro Solís, quien vuelve hoy a Chile después de tomardeclara- ción en Estados Unidos a los ex agentes de la Dina, MichaelE Townley y Armando Fer- nández Larios, trae en sus maletas la pieza de un puzzle que conecta el asesinato del ex comandante en jefe del Ejército, general Carlos Prats, con la muerte del Presidente Eduar- do Frei Montalva. Aunque ambos hechos ocurrieron con ocho años de diferencia, hay un nombre que se repite en ambas inves- tigaciones y que fue pronunciado por Townley ante Solís: Francisco Maxi- miliano Ferrer Lima. En el interrogatorio que hizo el magistrado, Townley mencionó a Ferrer Lima como uno de los miem- bros de la Dina que planificaron el atentado explosivo que en 1974 asesi- nó a Prats y a su esposa, Sofía Cuthbert, en Buenos Aires. Incluso, una de las novedades que arrojó la diligencia en Washington fue preci- samente, el casi seguro procesamiento de Ferrer, conocido en la Dina por su “chapa” de “capitán Max”. A cargo del BIE “Max” es un viejo conocido de Augusto Pinochet. No es casual que el general (r) lo haya mantenido en El ministro Sergio Solís hizo más de cien preguntas a Townley. EL DOCUMENTO DESCLASIFICADO Informe de EE.UU. avala la declaración de Townley en cuanto a la G Peter Kornbluh, Washington documentos desclasificados de Estados Militar, a lo que agregó datos ya conocidos, truyó una bomba que se detonaba a control Unidos, que señalan que al ex comandante ya que en 1998, la jueza argentina Servini remoto. -

Emelina Fuente S of Linare S, Eighty -Eight Years Old, Playing the Rabel, an Archaic Folk Violin of Chile

Emelina Fuente s of Linare s, eighty -eight years old, playing the rabel, an archaic folk violin of Chile. THE DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE, INSTITUTE FOR MUSICAL RESEARCH, UNIVERSITY OF CHILE Manuel Dannemann HISTORY The progenitor of the present Folklore Department of the In- stitute for Musical Research in the Faculty of Musical Arts and Sciences at the University of Chile in Santiago, was the Institute for Folk Music Research, established in 1943 upon the initiative of a committee composed of Eugenio Pereira, Alfonso Letelier, Vicente Salas, Carlos ~avin,Carlos Isamitt, Jorge Urrutia and Filomena Salas. Some members of this committee were also members of the Faculty of Fine Arts of that time, which encouraged this venture. Among the first activities of the newly formed Institute was the sponsorship of a series of concerts of folk and indigenous music performed by professional and amateur groups in various theatres in Santiago. During the same period the Symphony Orchestra of Chile gave concerts of Chilean art music influenced by the folk music of the country. Although these were not performances by groups of the culture in which the music originated, the music played was care- fully selected for its authenticity. The principal purpose of these concerts was to acquaint the public with the traditional music of Chile. The publication of the pamphlet, Chile? which was a guide to the afore- mentioned concerts, also served this purpose. However, its basic function was that of offering a total picture of the extant folk music. In addition, it included articles dealing with the methods used in the specialized study of folk music.