Art and Transformation Under State Repression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latitud 90 Get Inspired.Pdf

Dear reader, To Latitud 90, travelling is a learning experience that transforms people; it is because of this that we developed this information guide about inspiring Chile, to give you the chance to encounter the places, people and traditions in most encompassing and comfortable way, while always maintaining care for the environment. Chile offers a lot do and this catalogue serves as a guide to inform you about exciting, adventurous, unique, cultural and entertaining activities to do around this beautiful country, to show the most diverse and unique Chile, its contrasts, the fascinating and it’s remoteness. Due to the fact that Chile is a country known for its long coastline of approximately 4300 km, there are some extremely varying climates, landscapes, cultures and natures to explore in the country and very different geographical parts of the country; North, Center, South, Patagonia and Islands. Furthermore, there is also Wine Routes all around the country, plus a small chapter about Chilean festivities. Moreover, you will find the most important general information about Chile, and tips for travellers to make your visit Please enjoy reading further and get inspired with this beautiful country… The Great North The far north of Chile shares the border with Peru and Bolivia, and it’s known for being the driest desert in the world. Covering an area of 181.300 square kilometers, the Atacama Desert enclose to the East by the main chain of the Andes Mountain, while to the west lies a secondary mountain range called Cordillera de la Costa, this is a natural wall between the central part of the continent and the Pacific Ocean; large Volcanoes dominate the landscape some of them have been inactive since many years while some still present volcanic activity. -

New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005-2015)

New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005-2015) Paul Rumney Merchant St John’s College August 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005 – 2015) Paul Rumney Merchant This thesis explores the potential of domestic space to act as the ground for new forms of community and sociability in Argentine and Chilean films from the early twenty-first century. It thus tracks a shift in the political treatment of the home in Southern Cone cinema, away from allegorical affirmations of the family, and towards a reflection on film’s ability to both delineate and disrupt lived spaces. In the works examined, the displacement of attention from human subjects to the material environment defamiliarises the domestic sphere and complicates its relation to the nation. The house thus does not act as ‘a body of images that give mankind proofs or illusions of stability’ (Bachelard), but rather as a medium through which identities are challenged and reformed. This anxiety about domestic space demands, I argue, a renewal of the deconstructive frameworks often deployed in studies of Latin American culture (Moreiras, Williams). The thesis turns to new materialist theories, among others, as a supplement to deconstructive thinking, and argues that theorisations of cinema’s political agency must be informed by social, economic and urban histories. The prominence of suburban settings moreover encourages a nuancing of the ontological links often invoked between cinema, the house, and the city. The first section of the thesis rethinks two concepts closely linked to the home: memory and modernity. -

The Street Art Culture of Chile and Its Power in Art Education

Culture-Language-Media Degree of Master of Arts in Upper Secondary Education 15 Credits; Advanced Level “We Really Are Not Artists, We Are Military. We Are Soldiers” The Street Art Culture of Chile and its Power in Art Education “Vi är inte konstnärer, vi är militärer. Vi är sodlater” Gatukonstkulturen i Chile och dess påverkan på bildundervisning Granlund, Magdalena Silén, Maria Master of Art in Secondary Education: 300 Credits. Examiner: Edström, Ann-Mari. Opposition Seminar: 31/05/2018. Supervisor: Mars, Annette. Foreword We would like to give a big thanks to all those whom have helped made this thesis possible: to all the people we have been interviewing and that have been showing us the streets of Santiago and Valparaiso. To Kajsa, Micke and Robbin for making sure we met the right people while conducting this study. To Annette Mars for all the guidance prior- and during the conducting of this thesis. To Mauricio Veliz Campos for all the support we were given during the minor field studies scholarship application, as well as during our time in Santiago. To Vinboxgruppis for your constant support during the last five years. And last but not least to SIDA, for the trust and financial support. Thank you! This thesis is written during the spring of 2018. We, the writers behind this thesis, have both come up with the purpose, research questions, method, interview guide, as well as been taking visual street notes together. 2 Abstract This thesis describes the street art culture of Chile and its power in art education. The thesis highlights the didactic questions what, how and why. -

1 El Museo Nacional De Bellas Artes De Santiago

UNIVERSUM • Vol. 31 • Nº 1 • 2016 • Universidad de Talca Te National Museum of Fine Arts of Santiago and its publications (1922-2009) Albert Ferrer Orts – Alberto Madrid Letelier Pp. 141 a 151 THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS OF SANTIAGO AND ITS PUBLICATIONS (1922-2009)1 El Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Santiago (Chile) a través de sus publicaciones: 1922-2009 Albert Ferrer Orts* Alberto Madrid Letelier** 1 Tis article forms part of the project “Ausencia de una política o política de la ausencia. Institucionalidad y desarrollo de las artes visuales en Chile 1849-1973” Fondecyt Nº 1140370, whose co-researcher is one of the authors of this publication. Tis paper was initially sent for review in Spanish, and it has been translated into English with the support of the Project FP150008, “Aumento y mejora del índice de impacto y de la internacionalización de la revista Universum por medio de la publicación de un mayor número de artículos en inglés.” Fund for publication of Scientifc Journals 2015, Scientifc Information Program, Scientifc and Technological Research National Commission (Conicyt), Chile. Este artículo fue enviado a revisión inicialmente en español y ha sido traducido al inglés gracias al Proyecto FP150008, “Aumento y mejora del índice de impacto y de la internacionalización de la revista Universum por medio de la publicación de un mayor número de artículos en inglés”. Fondo de Publicación de Revistas Científcas 2015, Programa de Información Científca, Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científca y Tecnológica (Conicyt), Chile. * Faculty of Art, Universidad de Playa Ancha de Ciencias de la Educación. Valparaíso, Chile. -

SYLLABUS GLOBAL OPPORTUNITIES CHILEAN CULTURE Universidad De Los Andes, Santiago, Chile January 2Nd – January 23Rd, 2019

SYLLABUS GLOBAL OPPORTUNITIES CHILEAN CULTURE Universidad de los Andes, Santiago, Chile January 2nd – January 23rd, 2019 COURSE: GO CHILEAN CULTURE PREREQUISITES: None CREDITS: EVALUATIONS: 2 week program: 3 US Credits / 6 ECTS Written paper and presentation about Credits chosen topic related to Chilean Culture. 3 week program: 4 US Credits / 8 ECTS Online Placement Test for Language Course. Credits Final Language Exam. TOTAL HOURS: ON CAMPUS LECTURES: CULTURAL AND ACADEMIC TRIPS AND 2 week program: 40 2 week program: 30 hours ACTIVITIES: hours 3 week program: 44 hours 2 week program: 15 hours 3 week program: 60 3 week program: 20 hours hours COURSE DESCRIPTION This course’s main objective is to give students a deep understanding of Chile’s culture through a sociological point of view from the Prehispanic Period, until today, and how it has evolved through the different migratory waves. Additionally, the course will present a general view of Chile’s current cultural scenario through different perspectives. Finally, this course includes a Language Unit, that can be either Spanish for non-Spanish speakers, or English for Spanish speakers. METHODOLOGY AND ACTIVITIES This course will include lectures by different UANDES professors and external lecturers, that will involve student interaction. Students will have to choose a topic related to Chilean Culture on which they will work through the duration of the program and will have to present it at the end of the course. They will be graded in accordance to the development of the paper, and the final presentation. Finally, the language course will include a final exam during the last week of the program. -

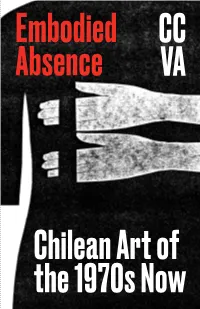

Embodied Absence Chilean Ar

Embodied Absence Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Carpenter Center Embodied Absence for the Visual Arts Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Oct 27, 2016–Jan 8, 2017 Works by Elías Adasme, Carmen This exhibition is co-organized Beuchat with Felipe Mujica and with DRCLAS as part of its research Johanna Unzueta, CADA (Colectivo project Conceptual Stumblings. Acciones de Arte), Francisco Copello, Exhibition and program support Luz Donoso, Juan Downey, Carlos is also provided by Harvard Leppe, Catalina Parra, Lotty University Committee on the Rosenfeld, UNAC (Unión por la Arts. The first iteration, Embodied Cultura), Cecilia Vicuña, and Raúl Absence: Ephemerality and Zurita with Cristóbal Lehyt Collectivity in Chilean Art of the 1970s (September 2015–January Guest curated by Liz Munsell, 2016), was organized by Museo Assistant Curator of Contemporary de la Solidaridad Salvador Art & Special Initiatives, Museum of Fine Allende, Santiago, Chile, with its Arts, Boston, and visiting curator, David substantial support in research Rockefeller Center for Latin American and production of works, in Studies (DRCLAS), Harvard University collaboration with DRCLAS. Embodied Absence Liz Munsell Following the U.S.-backed coup d’état in 1973,1 Chilean artists residing in Santiago and abroad created artworks that spoke to their experience of political, social, and geographic marginalization. Inside the country, they adopted the highly coded languages of conceptual art to evade censorship, exhibited work in public space in lieu of institutional support, and formed independently run galleries and artist collectives to protect their individual identities. Artists abroad staged public events and made artwork in solidarity with those at home. Their exhibitions, performances, interventions, and workshops spread awareness among international audiences and broke down isolating conditions within Chile. -

Emelina Fuente S of Linare S, Eighty -Eight Years Old, Playing the Rabel, an Archaic Folk Violin of Chile

Emelina Fuente s of Linare s, eighty -eight years old, playing the rabel, an archaic folk violin of Chile. THE DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE, INSTITUTE FOR MUSICAL RESEARCH, UNIVERSITY OF CHILE Manuel Dannemann HISTORY The progenitor of the present Folklore Department of the In- stitute for Musical Research in the Faculty of Musical Arts and Sciences at the University of Chile in Santiago, was the Institute for Folk Music Research, established in 1943 upon the initiative of a committee composed of Eugenio Pereira, Alfonso Letelier, Vicente Salas, Carlos ~avin,Carlos Isamitt, Jorge Urrutia and Filomena Salas. Some members of this committee were also members of the Faculty of Fine Arts of that time, which encouraged this venture. Among the first activities of the newly formed Institute was the sponsorship of a series of concerts of folk and indigenous music performed by professional and amateur groups in various theatres in Santiago. During the same period the Symphony Orchestra of Chile gave concerts of Chilean art music influenced by the folk music of the country. Although these were not performances by groups of the culture in which the music originated, the music played was care- fully selected for its authenticity. The principal purpose of these concerts was to acquaint the public with the traditional music of Chile. The publication of the pamphlet, Chile? which was a guide to the afore- mentioned concerts, also served this purpose. However, its basic function was that of offering a total picture of the extant folk music. In addition, it included articles dealing with the methods used in the specialized study of folk music. -

Street Art Of

Global Latin/o Americas Frederick Luis Aldama and Lourdes Torres, Series Editors “A detailed, incisive, intelligent, and well-argued exploration of visual politics in Chile that explores the way muralists, grafiteros, and other urban artists have inserted their aesthetics into the urban landscape. Not only is Latorre a savvy, patient sleuth but her dialogues with artists and audiences offer the reader precious historical context.” —ILAN STAVANS “A cutting-edge piece of art history, hybridized with cultural studies, and shaped by US people of color studies, attentive in a serious way to the historical and cultural context in which muralism and graffiti art arise and make sense in Chile.” —LAURA E. PERÉZ uisela Latorre’s Democracy on the Wall: Street Art of the Post-Dictatorship Era in Chile G documents and critically deconstructs the explosion of street art that emerged in Chile after the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, providing the first broad analysis of the visual vocabulary of Chile’s murals and graffiti while addressing the historical, social, and political context for this public art in Chile post-1990. Exploring the resurgence and impact of the muralist brigades, women graffiti artists, the phenomenon of “open-sky museums,” and the transnational impact on the development of Chilean street art, Latorre argues that mural and graffiti artists are enacting a “visual democracy,” a form of artistic praxis that seeks to create alternative images to those produced by institutions of power. Keenly aware of Latin America’s colonial legacy and Latorre deeply flawed democratic processes, and distrustful of hegemonic discourses promoted by government and corporate media, the artists in Democracy on the Wall utilize graffiti and muralism as an alternative means of public communication, one that does not serve capitalist or nationalist interests. -

Nelly Richard's Crítica Cultural: Theoretical Debates and Politico- Aesthetic Explorations in Chile (1970-2015)

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Nelly Richard’s crítica cultural : theoretical debates and politico-aesthetic explorations in Chile (1970- 2015) https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40178/ Version: Full Version Citation: Peters Núñez, Tomás (2016) Nelly Richard’s crítica cultural : theoretical debates and politico-aesthetic explorations in Chile (1970- 2015). [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London Nelly Richard's crítica cultural: Theoretical debates and politico- aesthetic explorations in Chile (1970-2015) Tomás Peters Núñez Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2016 This thesis was funded by the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica, Ministerio de Educación, Chile. 2 Declaration I, Tomás Peters Núñez, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Date 25/January/2016 3 ABSTRACT This thesis describes and analyses the intellectual trajectory of the Franco- Chilean cultural critic Nelly Richard between 1970 and 2015. Using a transdisciplinary approach, this investigation not only analyses Richard's series of theoretical, political, and essayistic experimentations, it also explores Chile’s artistic production (particularly in the visual arts) and political- cultural processes over the past 45 years. In this sense, it is an examination, on the one hand, of how her critical work and thought emerged in a social context characterized by historical breaks and transformations and, on the other, of how these biographical experiences and critical-theoretical experiments derived from a specific intellectual practice that has marked her professional profile: crítica cultural. -

Gender, Politics and Manga in Current Chilean Art

gaston j. muñoz j. Gender, Politics and Manga in Current Chilean Art Keywords: Contemporary painting, manga, gender, race, Chilean post-transition era Figure 1. Marco Arias 2000, from the El estado soy yo [I Am the State] series, acrylic, enamel, oil and fotocopy on canvas, 210 x 260 cm, 2015. Chilean painter Marco Arias created the work 2000 (fig. 1) not during the year its title signals, but in 2015 as part of a larger series called El estado soy yo (I Am the State). At first glance, we are taken by the many color- ful characters that are disposed over the canvas in a somewhat disshev- 115 elled, almost aleatory composition. We recognize many cartoon charac- ters with their schematic outlines, but also more realistic characters, and even a mix between both modes of representation. They vary in shape, color and size, and almost seem to be distributed according to an uniden- tified value scale. However, a closer inspection of the painting will lead us to appreciate a certain layering and box-like grid arrangement that ren- ders this particular piece of transcultural art a nostalgic one at its core. Arias was born in 1988, the same year that Augusto Pinochet’s dicta- torship was voted to a close over a national plebiscite. He was only two years old when Chile returned to democracy, and twelve years old at the turn of the century. This means that, growing up in the 1990s, the artist was introduced to a wide variety of media content through the television screen: current events, toy commercials, political news, and Japanese ani- me. -

Reading Chilean Street Art Through Postcolonial Theory

University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program Fall 2012 Reading Chilean Street Art through Postcolonial Theory: An Analysis of Subaltern Identity Formation in Santiaguino and Porteno Muralism Kara Gordon University of Colorado Boulder Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/honr_theses Recommended Citation Gordon, Kara, "Reading Chilean Street Art through Postcolonial Theory: An Analysis of Subaltern Identity Formation in Santiaguino and Porteno Muralism" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 289. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Honors Program at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reading Chilean Street Art through Postcolonial Theory: An Analysis of Subaltern Identity Formation in Santiaguino and Porteño Muralism Kara L. Gordon Undergraduate Honors Thesis Department of Art and Art History Advisor: Dr. Robert Nauman November 5, 2012 Committee Members: Frances Charteris, Program for Writing and Rhetoric Dr. Robert Nauman, Department of Art and Art History Dr. Kira van Lil, Department of Art and Art History TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................... ii ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION -

Fernando Prats Nature Paintings Fernando Prats Nature Paintings

FERNANDO PRATS NATURE PAINTINGS FERNANDO PRATS NATURE PAINTINGS 14.11.2018 - 25.01.2019 Puerta Roja, Hong Kong Detail of: Painting of Birds for a Private Residence 17 Smoke and bird-wing beat on paper, 178 x 261 cm, 2016 FOREWORD Since 2010 Puerta Roja has strived to build a cultural dialogue and uncover hidden narratives between focus on raising awareness of human connection to the environment, the resulting work Hong Kong and its Latin American and Spanish artists. Fernando Prats’ motivations can be traced will be donated to the fund-raising efforts of The Nature Conservancy in Asia Pacific. back to the rugged topography, intense weather and telluric forces of his native Chile. Linking to the I am deeply grateful to the Board of the Hong Kong Art Gallery Association, Ms. Alice Mong, profoundly rooted Taoist beliefs in relation to the destructive and creative balance of nature, as well as Executive Director of Asia Society Hong Kong Center and to Mr. Moses Tsang, an understanding of the invisible connections in our universe, Prats’ work comes to life in Hong Kong, Global Board Member and Co-Chair of the Asia-Pacific Council of Directors of where, despite its urban façade, the power of landscape and climate is ever-present. The Nature Conservancy, for making such a performance and resulting contribution possible. I am also grateful to Caroline Ha Thuc, one of the most influential curators in Hong Kong today Prats echoes Puerta Roja’s philosophy by marrying a profoundly intellectual and conceptual for her insightful views on Fernando Prats’ deep philosophical, intellectual and spiritual discourse with a poetic and robust aesthetic.