At a Glance: 2001-02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pre-Election Assessment Report June 1, 1992

A V InternationalFoundation for Electoral Systems 1620 I STREET, N.W. *SUITE6, ,vWASHINGTON, D.C. 20006. (202)828-8507 - FAX (202)452-0804 (202) 785-1672 GHANA: A PRE-ELECTION ASSESSMENT REPORT JUNE 1, 1992 Laurie A. Cooper Fred M. Hayward Anthony W.J. Lee This report was made possible by a grant from the U.S. Agency for International Development. This material is in the public domain and may be reproduced without permission; citation of IFES as the source would be - appreciated. BOARD OF F.Clifton White Patricia Hutar James M. Cannon David Jones Randa Teague DIRECTORS Chairman C. Secretary Counsel Richard M. Scammon Joseph Napolitan Charles Manatt John C.White Richard W.Soudriette Vice Chairman Treasurer Robert C.Walker Director TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................... 1 I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 3 II. BACKGROUND TO THE DEMOCRATIZATION PROCESS .............. 5 Economic and Infrastructural Background ......................... 5 Political Background ...................................... 6 The New Constitution ..................................... 9 National Commission for Democracy .......................... 9 Committee of Experts ................................... 10 National Consultative Assembly .............................. 10 The Constitution ....................................... 11 Civil Liberties .... .................................... 12 III. ELECTION POLICIES AND PROCEDURES ...................... 14 Referendum Observations .................................. -

Democracy Watch 6 & 7

Democracy Watch Vol. 2, No. 2&3 April-September 2001 1 A Quarterly Newsletter of the Ghana Center for Democratic Development 6&7 DemocracyWatch 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 statements. The openness to the media Volume 2, No. 2&3 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 was underscored by President Kufuors April-September 2001 The Media in the news conference to mark his first 100 Post Rawlings Era days in office, an event never witnessed ISSN: 0855-417X during the 19 years ex-President Rawlings was in power. A new era of positive government- In this issue media relations? In an early gesture of acknowledging the contribution of the media to Ghanaian Among the media, media watchers, democratic development, the NPP and observers of Ghanaian politics, government decided to abort ongoing EThe Media in the Post Rawlings Era there is a well-justified feeling of relief state prosecutions against journalists for .................Page 1 and euphoria over the demise of a criminal and or seditious libel. Most media unfriendly-regime. Indeed, it significantly, it has made good on its promise to repeal the obnoxious criminal E The New Challenges in Intra-media was expected that the relationship Relations ............. -

African Liberation and Unity in Nkrumah's Ghana

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/36074 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Grilli, Matteo Title: African liberation and unity in Nkrumah's Ghana : a study of the role of "Pan- African Institutions" in the making of Ghana's foreign policy, 1957 - 1966 Issue Date: 2015-11-03 Introduction Almost sixty years after its fall - occurred in a coup d'état on 24 February 1966 - Nkrumah‟s government in Ghana is still unanimously considered as one of the most influential but also controversial political experiences in the history of modern Africa. Its importance lies undoubtedly in the peculiarities of its internal policies and in the influence it exerted in Africa during the crucial years of the first wave of independence. Several aspects of Nkrumah‟s policy led this small West African country - without any visible strategic relevance – to act as a political giant becoming the torchbearer of Pan-Africanism and socialism in the continent. Between 1957 and 1966, Nkrumah transformed Ghana into a political laboratory where he could actualize his vision, known since 1960 as “Nkrumahism”.i This vision can be summarized as the achievement of three goals: national unity, economic transformation (towards socialism) and Africa‟s total liberation and unity.ii The latter point of Nkrumah‟s political agenda coincided with the actualization of Pan- Africanism and will be defined in this thesis as Ghana‟s Pan-African policy.iii In line with the indications of the 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress, Nkrumah considered the independence of his country only as the first step towards the liberation and unification of the whole continent. -

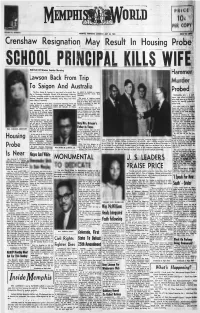

Crenshaw Resignation May Result in Housing Probe

I* » rl fl Memphis XI c MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE, SATURDAY, JULY 24, 1965 PRICE TEN CENTS Crenshaw Resignation May Result In Housing Probe X i ' ! Will Tell Of Mission Sunday Morning Hammer Lawson Back From Trip To Saigon And Australia Probed The Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr. was back in his pulpit Sun he talked to students at Sidney day at Centenary Methodist Church, 878 Mississippi, following University and New South Wale University. TUSCUMBIA, Ala. - A well- a 20-day round-the-world trip that included stops in Paris, Rome, known high school principal .1» Bombay, Bangkok, Saigon, Cambodia, Hong Kong and three The group of religious leaders being held here on a charge of major cities in Australia. spent five days in Saigon and then went on to Hong Kong where they slaying his equally prominent Rev. Mr. Lawson was on a peace in Australia addressing church and drafted a statement on their ob teacher-wife. seeking mission as a member of student groups In Sidney, Mel servations and findings. the Fellowship of Reconciliation bourne and Adelaide. In Sidney, The school head is in Colbert At the beginning of the trip, the through its Clergymen's Emer County jail where he faces first »J American churchmen spent three degree murder charges for the ham*., gency Committee for Viet Nam. days in Bangkok where they mapp mer killing of his mate late last He was one of 12 religious leaders ed their program for Saigon after Thursday night. froming the American team which conferring with government offic was joined by another group from Clinton K. -

Africa in London

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURRENT 'ORLD AFFAIRS CJP-2 November 20, 1961 Africa in London. 93 Cornwall Gardens London, S.W. 7., England Mr. Richard H. Nolte, Institute of Current World Affairs, 366 Madison Avenue, New York 17, New York. Dear Mr. Nolte- My immersion into Africa in London began in a burst of black chauffeur driven lolls-Royces, the happy sounds of the High Lifeand a taste of the internal politics of the Federation of Nigeria. All this took place at the residence of Chief Akintoye Coker, Agent-General for Western Nigeria in the United Kingdom. Chief Coker's home, an aging but stately London mansion, sits across the road from Kensington Palace, the home of Princess Margaret and the Earl of Snowdon. The sleek and shiny lolls-IKoyces pulled up in front of the portico of the Agent- General's home and discharged African passengers in flowing robes of many shades and many colours. English chauffeurs clad in dark blue uniforms parked the cars in the courtyard to await the return of their passengers. They stood by the cars.and held conversations on the current state of English cricket, the pay pause and other peculiarly English things. In the house, the invitation was handed to a young African civil servant dressed in what would seem to be a kind of uniform for African civil servants in London, a dark blue three piece suit. Walking down a long softly carpeted hall- way to the Ballroom, we stepped through the door into a galaxy of colourful, magnificent, swinging robes punctuated by the grey and blue of business suits. -

Vietnam - Commonwealth Mission (Peace in Viet-Nam)

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 19 Date 30/05/2006 Time 9:35:51 AM S-0871-0002-07-00001 Expanded Number S-0871 -0002-07-00001 Title items-in-Peace-keeping operations - Vietnam - Commonwealth Mission (peace in Viet-Nam) Date Created 17/06/1965 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0871 -0002: Peace-Keeping Operations Files of the Secretary-General: U Thant - Viet-Nam Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit STATEMSNTSSUEATMEET[NGOFCOMONWEALTH 17_June_,._1965 The meeting of Commonwealth Heads of Government began their discussion of the international situation this afternoon by considering the position in Vietnam. They '//ere deeply concerned by the increasing gravity of the situation and the urgency of re-establishing conditions in which the people of Vietnam may be able again to live in peace. They believed that the Commonwealth, united in their desire to promote peace in the world, might make a contribution to this end by an initiative designed to bring hostilities to a speedy conclusion, They therefore resolved that a mission, composed of the leaders of some Commonwealth countries, should, on their behalf, make contact with the Governments principally concerned with the problem of Vietnam in order to ascertain how far there may be common ground about the circumstances in which a conference might be held leading to the establishment of a just and lasting peace in Vietnam. CONFIDENTIAL %- TEXT OF MESSAGE TO BE DELIVERED TO THE GOVERNMENTS OF THE REPUBLIC OF VIETNAM (SOUTH VIETNAM), THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF VIETNAM (NORTH VIETNAM), OF THE U.S.S.E., OF THE CHINESE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC AND OF THE U.S.A., BY THE REPRESENTATIVES OF THE GOVERNMENTS OF THE UNITED KINGDOM, GHANA, NIGERIA AND TRINIDAD. -

![[Ghanabib 1819 – 1979 Prepared 23/11/2011] [Ghanabib 1980 – 1999 Prepared 30/12/2011] [Ghanabib 2000 – 2005 Prepared 03/03](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5636/ghanabib-1819-1979-prepared-23-11-2011-ghanabib-1980-1999-prepared-30-12-2011-ghanabib-2000-2005-prepared-03-03-6245636.webp)

[Ghanabib 1819 – 1979 Prepared 23/11/2011] [Ghanabib 1980 – 1999 Prepared 30/12/2011] [Ghanabib 2000 – 2005 Prepared 03/03

[Ghanabib 1819 – 1979 prepared 23/11/2011] [Ghanabib 1980 – 1999 prepared 30/12/2011] [Ghanabib 2000 – 2005 prepared 03/03/2012] [Ghanabib 2006 – 2009 prepared 09/03/2012] GHANAIAN THEATRE A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SOURCES A WORK IN PROGRESS BY JAMES GIBBS File Ghana. Composite on ‘Ghana’ 08/01/08 Nolisment Publications 2006 edition The Barn, Aberhowy, Llangynidr Powys NP8 1LR, UK 9 ISBN 1-899990-01-1 The study of their own ancient as well as modern history has been shamefully neglected by educated inhabitants of the Gold Coast. John Mensah Sarbah, Fanti National Constitution. London, 1906, 71. This document is a response to a need perceived while teaching in the School of Performing Arts, University of Ghana, during 1994. In addition to primary material and articles on the theatre in Ghana, it lists reviews of Ghanaian play-texts and itemizes documents relating to the Ghanaian theatre held in my own collection. I have also included references to material on the evolution of the literary culture in Ghana, and to anthropological studies. The whole reflects an awareness of some of the different ways in which ‘theatre’ has been defined over the decades, and of the energies that have been expended in creating archives and check-lists dedicated to the sister of arts of music and dance. It works, with an ‘inclusive’ bent, on an area that focuses on theatre, drama and performance studies. When I began the task I found existing bibliographical work, for example that of Margaret D. Patten in relation to Ghanaian Imaginative Writing in English, immensely useful, but it only covered part of the area of interest. -

Ghana and the West

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA TRE DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE POLITICHE DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN SCIENZE POLITICHE CURRICULUM “STUDI EUROPEI E INTERNAZIONALI” XXVIII CICLO Tesi Dottorale From “Our Experiment” to the “Prisoner of the West”: Ghana’s Relations with Great Britain, the United States of America and West Germany during Kwame Nkrumah’s Government (1957-1966) Candidato: Matteo E. Landricina Supervisore: Prof. Alessandro Volterra Coordinatore del Dottorato: Prof. Leopoldo Nuti A Clea Table of Contents Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... vi Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ vii Literature Review ........................................................................................................................................... x Outline and Methodology of the Present Study ............................................................................................ xx Chapter I: The United Kingdom and Ghana ......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Ghana, Nkrumah, and Britain’s Decolonization .............................................................................. 1 Development for whom? ............................................................................................................................... 3 A Black Democracy? The “Ghana -

I UNIVERSITY of CAPE COAST DR. HILLA LIMANN 1934

UNIVERSITY OF CAPE COAST DR. HILLA LIMANN 1934 – 1998: HIS LIFE AND TIMES BY AGAPE KANYIRI DAMWAH Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Cape Coast in partial fulfillment of the requirements for award of Master of Philosophy Degree in History. JUNE, 2011 i DECLARATION Candidate’s Declaration I hereby declare that this dissertation is the result of my own original work and that no part of it has been presented for another degree in this university or elsewhere. Name: Agape Kanyiri Damwah Signature: ……………………………………Date:……………………………… Supervisors’ Declaration We hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of this thesis were supervised in accordance with the guidelines on supervision of thesis laid down by the University of Cape Coast. Principal Supervisor’s Name: Prof. B. G. Der Signature: ………………………………….. Date:.................................................. Co-Supervisor’s Name: Dr. S. Y. Boadi-Siaw Signature……………………… ……………Date………………………………… ii ABSTRACT The work takes a critical look at the life and times of Dr. Hilla Limann, President of the Third Republic of Ghana. The thesis offers readers an insight into the life, struggle, works, successes and the failures of Hilla Limann. The work endeavours to examine the life of Hilla Limann and his meteoric rise to power in 1979. Through his own persuasion, determination and hard work, Limann pursued the educational ladder outside Ghana and became a well-educated man. The study discovered that Limann was not a novice in politics and social leadership. In theory he had undergone rigorous academic discipline. Between 1965 and 1978, he worked with Ghana’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs where he played various high profile roles at the Foreign Missions. -

The Rhetoric of Kwame Nkrumah: an Analysis of His Political Speeches

i THE RHETORIC OF KWAME NKRUMAH: AN ANALYSIS OF HIS POLITICAL SPEECHES. By Town Eric Opoku Mensah MPhil (English Language), UCC B.A. Hons (EnglishCape Language), UCC of Thesis Presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Centre for Rhetoric Studies, UniversityFaculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN February 2014 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to use this opportunity to express my utmost gratitude to the many special individuals whose advice, support and love helped me to complete this thesis. My warmest appreciation goes to Distinguished Professor Philippe-Joseph Salazar, my doctoral supervisor. My encounter with Professor Salazar opened a new page in my research life. Whilst I initially anticipated a close-knit supervision relation, I came to experience a rather physically distant but close relationship. Professor Salazar strategically allowed me to ‘wonder in the woods’ for months. I was later to acknowledge that that difficult and lonely period was to allow me to form clearly and gain a deeper understanding of my research problem. Prof’s style has ultimately helped in shaping my own independent thinking and has helped me to find my academic voice, a voice which is a quintessential too in this whole academic journey. -

Governance, Wealth Creation and Development in Africa: the Challenges and the Prospects

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 4, Issue 2 | Summer 2000 Governance, Wealth Creation and Development in Africa: The Challenges and the Prospects JOHN MUKUM MBAKU Abstract: Available evidence shows that human conditions in most African countries have deteriorated significantly in recent years. In fact, since many African countries began to gain independence in the 1960s, the standard of living for most Africans has either not improved or has done so only marginally. The general consensus among many observers--including researchers, aid donors, and even African policymakers--is that unless appropriate (and drastic) measures are undertaken, economic, social and human conditions in the continent will continue to worsen. Today, most African countries are unable to generate the wealth they need to deal fully and effectively with mass poverty and deprivation, and as result, must depend on the industrial North for food and development aid. This paper examines impediments to wealth creation in Africa and argues that continued poverty and deprivation in the continent are made possible by the institutional arrangements that Africans adopted at independence. In order to prepare for sustainable development in the new century, Africans must engage in state reconstruction to provide themselves with governance structures that minimize political opportunism (e.g., bureaucratic corruption and rent seeking), and resource allocation systems that enhance indigenous entrepreneurship and promote wealth creation. Introduction Many developing countries have been able to achieve self-sufficiency in foodstuff production as a result of rapid economic growth during the last four decades. In addition, they have significantly improved the quality of life for their citizens. Unfortunately, the kind of strong macroeconomic performance that has allowed many of these countries to successfully deliver major improvements in the national welfare has not been universal. -

Youth and Popular Politics in Ghana, C. 1900-1979

"And still the Youth are coming": Youth and popular politics in Ghana, c. 1900-1979 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Asiedu-Acquah, Emmanuel. 2015. "And still the Youth are coming": Youth and popular politics in Ghana, c. 1900-1979. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17467195 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “And still the Youth are coming”: Youth and popular politics in Ghana, c. 1900-1979 A dissertation presented by Emmanuel Asiedu-Acquah to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Emmanuel Asiedu-Acquah All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Emmanuel Akyeampong Emmanuel Asiedu-Acquah “And still the Youth are coming”: Youth and popular politics in Ghana, c. 1900- 1979 Abstract This dissertation explores the significance of the youth in the popular politics of 20th- century Ghana. Based on two and half years of archival and field research in Ghana and Britain, the dissertation investigates the political agency of the youth, especially in the domains of youth associations, student politics, and popular culture. It also examines the structural factors in the colonial and postcolonial periods that shaped youth political engagement, and how youth worked within and without these structural frames to shape popular politics.