Part 4: Thrust Tectonics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linking Megathrust Earthquakes to Brittle Deformation in a Fossil Accretionary Complex

ARTICLE Received 9 Dec 2014 | Accepted 13 May 2015 | Published 24 Jun 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8504 OPEN Linking megathrust earthquakes to brittle deformation in a fossil accretionary complex Armin Dielforder1, Hauke Vollstaedt1,2, Torsten Vennemann3, Alfons Berger1 & Marco Herwegh1 Seismological data from recent subduction earthquakes suggest that megathrust earthquakes induce transient stress changes in the upper plate that shift accretionary wedges into an unstable state. These stress changes have, however, never been linked to geological structures preserved in fossil accretionary complexes. The importance of coseismically induced wedge failure has therefore remained largely elusive. Here we show that brittle faulting and vein formation in the palaeo-accretionary complex of the European Alps record stress changes generated by subduction-related earthquakes. Early veins formed at shallow levels by bedding-parallel shear during coseismic compression of the outer wedge. In contrast, subsequent vein formation occurred by normal faulting and extensional fracturing at deeper levels in response to coseismic extension of the inner wedge. Our study demonstrates how mineral veins can be used to reveal the dynamics of outer and inner wedges, which respond in opposite ways to megathrust earthquakes by compressional and extensional faulting, respectively. 1 Institute of Geological Sciences, University of Bern, Baltzerstrasse 1 þ 3, Bern CH-3012, Switzerland. 2 Center for Space and Habitability, University of Bern, Sidlerstrasse 5, Bern CH-3012, Switzerland. 3 Institute of Earth Surface Dynamics, University of Lausanne, Geˆopolis 4634, Lausanne CH-1015, Switzerland. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to A.D. (email: [email protected]). NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | 6:7504 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8504 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 & 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. -

Tectonic Imbrication and Foredeep Development in the Penokean

Tectonic Imbrication and Foredeep Development in the Penokean Orogen, East-Central Minnesota An Interpretation Based on Regional Geophysics and the Results of Test-Drilling The Penokean Orogeny in Minnesota and Upper Michigan A Comparison of Structural Geology U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1904-C, D AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the cur rent-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Sur vey publications released prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that are listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" are no longer available. Prices of reports released to the open files are given in the listing "U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports," updated month ly, which is for sale in microfiche from the U.S. Geological Survey, Books and Open-File Reports Section, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices given below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications of general in Books of the U.S. -

Significance of Brittle Deformation in the Footwall

Journal of Structural Geology 64 (2014) 79e98 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Structural Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jsg Significance of brittle deformation in the footwall of the Alpine Fault, New Zealand: Smithy Creek Fault zone J.-E. Lund Snee a,*,1, V.G. Toy a, K. Gessner b a Geology Department, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9016, New Zealand b Western Australian Geothermal Centre of Excellence, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia article info abstract Article history: The Smithy Creek Fault represents a rare exposure of a brittle fault zone within Australian Plate rocks that Received 28 January 2013 constitute the footwall of the Alpine Fault zone in Westland, New Zealand. Outcrop mapping and Received in revised form paleostress analysis of the Smithy Creek Fault were conducted to characterize deformation and miner- 22 May 2013 alization in the footwall of the nearby Alpine Fault, and the timing of these processes relative to the Accepted 4 June 2013 modern tectonic regime. While unfavorably oriented, the dextral oblique Smithy Creek thrust has Available online 18 June 2013 kinematics compatible with slip in the current stress regime and offsets a basement unconformity beneath Holocene glaciofluvial sediments. A greater than 100 m wide damage zone and more than 8 m Keywords: Fault zone wide, extensively fractured fault core are consistent with total displacement on the kilometer scale. e Fluid flow Based on our observations we propose that an asymmetric damage zone containing quartz carbonate Hydrofracture echloriteeepidote veins is focused in the footwall. -

GEO 2008 Conference Abstracts, Bahrain GEO 2008 Conference Abstracts

GEO 2008 conference abstracts, Bahrain GEO 2008 Conference Abstracts he abstracts of the GEO 2008 Conference presentations (3-5 March 2008, Bahrain) are published in Talphabetical order based on the last name of the first author. Only those abstracts that were accepted by the GEO 2008 Program Committee are published here, and were subsequently edited by GeoArabia Editors and proof-read by the corresponding author. Several names of companies and institutions to which presenters are affiliated have been abbreviated (see page 262). For convenience, all subsidiary companies are listed as the parent company. (#117804) Sandstone-body geometry, facies existing data sets and improve exploration decision architecture and depositional model of making. The results of a recent 3-D seismic reprocessing Ordovician Barik Sandstone, Oman effort over approximately 1,800 square km of data from the Mediterranean Sea has brought renewed interest in Iftikhar A. Abbasi (Sultan Qaboos University, Oman) deep, pre-Messinian structures. Historically, the reservoir and Abdulrahman Al-Harthy (Sultan Qaboos targets in the southern Mediterranean Sea have been the University, Oman <[email protected]>) Pliocene-Pleistocene and Messinian/Pre-Messinian gas sands. These are readily identifiable as anomalousbright The Lower Paleozoic siliciclastics sediments of the amplitudes on the seismic data. The key to enhancing the Haima Supergroup in the Al-Haushi-Huqf area of cen- deeper structure is multiple and noise attenuation. The tral Oman are subdivided into a number of formations Miocene and older targets are overlain by a Messinian- and members based on lithological characteristics of aged, structurally complex anhydrite layer, the Rosetta various rock sequences. -

326-97 Lab Final S.D

Geol 326-97 Name: KEY 5/6/97 Class Ave = 101 / 150 Geol 326-97 Lab Final s.d. = 24 This lab final exam is worth 150 points of your total grade. Each lettered question is worth 15 points. Read through it all first to find out what you need to do. List all of your answers on these pages and attach any constructions, tracing paper overlays, etc. Put your name on all pages. 1. One way to analyze brittle faults is to calculate and plot the infinitesimal shortening and extension directions on a lower hemisphere, stereographic projection. These principal axes lie in the “movement plane”, which contains the pole to the fault plane and the slickensides, and are at 45° to the pole. The following questions apply to a single fault described in part (a), below: (a) A fault has a strike and dip of 250, 57 N and the slickensides have a rake of 63°, measured from the given strike azimuth. Plot the orientations of the fault plane and the slickensides on an equal area projection. (b) Bedding in the vicinity of the fault is oriented 37, 42 E. Assuming that the fault formed when the bedding was horizontal, determine and plot the original geometry of the fault and the slickensides. (c) Determine the original (pre-rotation)orientation of the infinitesimal shortening and extension axes for fault. 2. All of the following questions apply to the map shown on the next page. In all of the rocks with cleavage, you may assume that both cleavage and bedding strike 024°. -

The Geology of the Enosburg Area, Vermont

THE GEOLOGY OF THE ENOSBURG AREA, VERMONT By JOlIN G. DENNIS VERMONT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. DOLL, State Geologist Published by VERMONT DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT MONTPELIER, VERMONT BULLETIN No. 23 1964 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT 7 INTRODUCTION ...................... 7 Location ........................ 7 Geologic Setting .................... 9 Previous Work ..................... 10 Method of Study .................... 10 Acknowledgments .................... 10 Physiography ...................... 11 STRATIGRAPHY ...................... 12 Introduction ...................... 12 Pinnacle Formation ................... 14 Name and Distribution ................ 14 Graywacke ...................... 14 Underhill Facics ................... 16 Tibbit Hill Volcanics ................. 16 Age......................... 19 Underhill Formation ................... 19 Name and Distribution ................ 19 Fairfield Pond Member ................ 20 White Brook Member ................. 21 West Sutton Slate ................... 22 Bonsecours Facies ................... 23 Greenstones ..................... 24 Stratigraphic Relations of the Greenstones ........ 25 Cheshire Formation ................... 26 Name and Distribution ................ 26 Lithology ...................... 26 Age......................... 27 Bridgeman Hill Formation ................ 28 Name and Distribution ................ 28 Dunham Dolomite .................. 28 Rice Hill Member ................... 29 Oak Hill Slate (Parker Slate) .............. 29 Rugg Brook Dolomite (Scottsmore -

Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and Northern Oman Mountains: from Ophiolite Obduction to Continental Collision

GeoArabia, 2014, v. 19, no. 2, p. 135-174 Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and northern Oman Mountains: From ophiolite obduction to continental collision Michael P. Searle, Alan G. Cherry, Mohammed Y. Ali and David J.W. Cooper ABSTRACT The tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula in northern Oman shows a transition between the Late Cretaceous ophiolite emplacement related tectonics recorded along the Oman Mountains and Dibba Zone to the SE and the Late Cenozoic continent-continent collision tectonics along the Zagros Mountains in Iran to the northwest. Three stages in the continental collision process have been recognized. Stage one involves the emplacement of the Semail Ophiolite from NE to SW onto the Mid-Permian–Mesozoic passive continental margin of Arabia. The Semail Ophiolite shows a lower ocean ridge axis suite of gabbros, tonalites, trondhjemites and lavas (Geotimes V1 unit) dated by U-Pb zircon between 96.4–95.4 Ma overlain by a post-ridge suite including island-arc related volcanics including boninites formed between 95.4–94.7 Ma (Lasail, V2 unit). The ophiolite obduction process began at 96 Ma with subduction of Triassic–Jurassic oceanic crust to depths of > 40 km to form the amphibolite/granulite facies metamorphic sole along an ENE- dipping subduction zone. U-Pb ages of partial melts in the sole amphibolites (95.6– 94.5 Ma) overlap precisely in age with the ophiolite crustal sequence, implying that subduction was occurring at the same time as the ophiolite was forming. The ophiolite, together with the underlying Haybi and Hawasina thrust sheets, were thrust southwest on top of the Permian–Mesozoic shelf carbonate sequence during the Late Cenomanian–Campanian. -

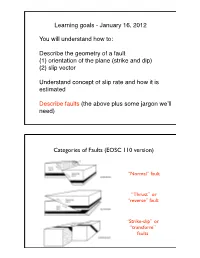

Describe the Geometry of a Fault (1) Orientation of the Plane (Strike and Dip) (2) Slip Vector

Learning goals - January 16, 2012 You will understand how to: Describe the geometry of a fault (1) orientation of the plane (strike and dip) (2) slip vector Understand concept of slip rate and how it is estimated Describe faults (the above plus some jargon weʼll need) Categories of Faults (EOSC 110 version) “Normal” fault “Thrust” or “reverse” fault “Strike-slip” or “transform” faults Two kinds of strike-slip faults Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) Stand with your feet on either side of the fault. Which side comes toward you when the fault slips? Another way to tell: stand on one side of the fault looking toward it. Which way does the block on the other side move? Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) 1992 M 7.4 Landers, California Earthquake rupture (SCEC) Describing the fault geometry: fault plane orientation How do you usually describe a plane (with lines)? In geology, we choose these two lines to be: • strike • dip strike dip • strike is the azimuth of the line where the fault plane intersects the horizontal plane. Measured clockwise from N. • dip is the angle with respect to the horizontal of the line of steepest descent (perpendic. to strike) (a ball would roll down it). strike “60°” dip “30° (to the SE)” Profile view, as often shown on block diagrams strike 30° “hanging wall” “footwall” 0° N Map view Profile view 90° W E 270° S 180° Strike? Dip? 45° 45° Map view Profile view Strike? Dip? 0° 135° Indicating direction of slip quantitatively: the slip vector footwall • let’s define the slip direction (vector) -

Geologic Map of the Yellow Pine Quadrangle, Valley County, Idaho

IDAHO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY IDAHOGEOLOGY.ORG DIGITAL WEB MAP 190 MOSCOW AND BOISE STEWART AND OTHERS present in exposures in the southern part of the map. Quartzite is feldspar The Johnson Creek shear zone is a major regional structure (Lund, 2004). To PIONEER GROUP (CH0776) poor. Thickness unknown because of complex internal folding and the the south of the quadrangle it can be traced as a series of faults (Fisher and 19DS16 GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE YELLOW PINE QUADRANGLE, VALLEY COUNTY, IDAHO The Pioneer group is a prospected area located northeast of the mouth of presence of a foliation that may or may not be transposed bedding. Likely others, 1992; Stewart and others, 2018), none of which appear to be as equivalent to the quartzite and schist unit in the Stibnite roof pendant silicified as in the Yellow Pine area. One splay likely connects to the Dead- Riordan Creek. One Defense Minerals Administration (DMA) application Cambrian y CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS and one Defense Minerals Exploration Administration (DMEA) loan appli- t i mapped by Stewart and others (2016). wood fault, which is locally mineralized at and southwest of the Deadwood l i lower cation were made in the 1950s for claims in this area, details of which are b Mine (Kiilsgaard and others, 2006). To the north, north of the Red Mountain a b Zmsm Marble of Moores Station Formation (Neoproterozoic)—Discontinuous lenses available in Frank (2016). Prospects at slightly lower elevation were termed o qtzite David E. Stewart, Reed S. Lewis, Eric D. Stewart, and Zachery M. Lifton stockwork, the fault zone is intruded by voluminous Eocene dikes (Lund, r p of buff to light-gray marble and lesser amounts of millimeter- to the Syringa Group (DMA Docket 1036). -

Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2014-06-11 Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence Scott Royal Greenhalgh Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Greenhalgh, Scott Royal, "Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 4095. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4095 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence Scott R. Greenhalgh A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science John H. McBride, Chair Brooks B. Britt Bart J. Kowallis John M. Bartley Department of Geological Sciences Brigham Young University April 2014 Copyright © 2014 Scott R. Greenhalgh All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Along Strike Variability of Thrust-Fault Vergence Scott R. Greenhalgh Department of Geological Sciences, BYU Master of Science The kinematic evolution and along-strike variation in contractional deformation in over- thrust belts are poorly understood, especially in three dimensions. The Sevier-age Cordilleran overthrust belt of southwestern Wyoming, with its abundance of subsurface data, provides an ideal laboratory to study how this deformation varies along the strike of the belt. We have per- formed a detailed structural interpretation of dual vergent thrusts based on a 3D seismic survey along the Wyoming salient of the Cordilleran overthrust belt (Big Piney-LaBarge field). -

Development of the Rocky Mountain Foreland Basin: Combined Structural

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2007 DEVELOPMENT OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN FORELAND BASIN: COMBINED STRUCTURAL, MINERALOGICAL, AND GEOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF BASIN EVOLUTION, ROCKY MOUNTAIN THRUST FRONT, NORTHWEST MONTANA Emily Geraghty Ward The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ward, Emily Geraghty, "DEVELOPMENT OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN FORELAND BASIN: COMBINED STRUCTURAL, MINERALOGICAL, AND GEOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF BASIN EVOLUTION, ROCKY MOUNTAIN THRUST FRONT, NORTHWEST MONTANA" (2007). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1234. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1234 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEVELOPMENT OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN FORELAND BASIN: COMBINED STRUCTURAL, MINERALOGICAL, AND GEOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF BASIN EVOLUTION ROCKY MOUNTAIN THRUST FRONT, NORTHWEST MONTANA By Emily M. Geraghty Ward B.A., Whitman College, Walla Walla, WA, 1999 M.S., Washington State University, Pullman, WA, 2002 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geology The University of Montana Missoula, MT Spring 2007 Approved by: Dr. David A. Strobel, Dean Graduate School James W. Sears, Chair Department of Geosciences Julia A. Baldwin Department of Geosciences Marc S. Hendrix Department of Geosciences Steven D. -

Tectonic Klippe Served the Needs of Cult Worship, Sanctuary of Zeus, Mount Lykaion, Peloponnese, Greece

Tectonic Klippe Served the Needs of Cult Worship, Sanctuary of Zeus, Mount Lykaion, Peloponnese, Greece George H. Davis, Dept. of Geosciences, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA, [email protected] ABSTRACT Mount Lykaion is a rare, historical, cul- tural phenomenon, namely a Late Bronze Age through Hellenistic period (ca. 1500– 100 BC) mountaintop Zeus sanctuary, built upon an unusual tectonic feature, namely a thrust klippe. Recognition of this klippe and its physical character provides the framework for understanding the cou- pling between the archaeology and geology of the site. It appears that whenever there were new requirements in the physical/ cultural expansion of the sanctuary, the overall geologic characteristics of the thrust klippe proved to be perfectly adapt- able. The heart of this analysis consists of detailed geological mapping, detailed structural geologic analysis, and close cross-disciplinary engagement with archaeologists, classicists, and architects. INTRODUCTION Figure 1. Location of the Sanctuary of Zeus, Mount Lykaion, Peloponnese, Greece. In the second century AD, Pausanias authored an invaluable description of the residual worked blocks of built structures The critical geologic emphasis here is Sanctuary of Zeus, Mount Lykaion, and activity areas, including a hippodrome that Mount Lykaion is a thrust klippe. located at latitude 37° 23′ N, longitude and stadium used for athletic games in Thrusting was achieved during tectonic 22° 00′ E, in the Peloponnese (Fig. 1). ancient times (see Romano and Voyatzis, inversion of Jurassic to early Cenozoic Pausanias’ accounts were originally writ- 2014, 2015). Pindos Basin stratigraphy (Degnan and ten in Greek and are available in a number In 2004, I signed on as geologist for the Robertson, 2006; Doutsos et al., 1993; of translations and commentaries, includ- Mount Lykaion Excavation and Survey Skourlis and Doutsos, 2003).