Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and Northern Oman Mountains: from Ophiolite Obduction to Continental Collision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linking Megathrust Earthquakes to Brittle Deformation in a Fossil Accretionary Complex

ARTICLE Received 9 Dec 2014 | Accepted 13 May 2015 | Published 24 Jun 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8504 OPEN Linking megathrust earthquakes to brittle deformation in a fossil accretionary complex Armin Dielforder1, Hauke Vollstaedt1,2, Torsten Vennemann3, Alfons Berger1 & Marco Herwegh1 Seismological data from recent subduction earthquakes suggest that megathrust earthquakes induce transient stress changes in the upper plate that shift accretionary wedges into an unstable state. These stress changes have, however, never been linked to geological structures preserved in fossil accretionary complexes. The importance of coseismically induced wedge failure has therefore remained largely elusive. Here we show that brittle faulting and vein formation in the palaeo-accretionary complex of the European Alps record stress changes generated by subduction-related earthquakes. Early veins formed at shallow levels by bedding-parallel shear during coseismic compression of the outer wedge. In contrast, subsequent vein formation occurred by normal faulting and extensional fracturing at deeper levels in response to coseismic extension of the inner wedge. Our study demonstrates how mineral veins can be used to reveal the dynamics of outer and inner wedges, which respond in opposite ways to megathrust earthquakes by compressional and extensional faulting, respectively. 1 Institute of Geological Sciences, University of Bern, Baltzerstrasse 1 þ 3, Bern CH-3012, Switzerland. 2 Center for Space and Habitability, University of Bern, Sidlerstrasse 5, Bern CH-3012, Switzerland. 3 Institute of Earth Surface Dynamics, University of Lausanne, Geˆopolis 4634, Lausanne CH-1015, Switzerland. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to A.D. (email: [email protected]). NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | 6:7504 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8504 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 & 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. -

Uae Visa & Border Pass Requirements

UAE VISA & BORDER PASS REQUIREMENTS Arrival at Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE) Some visitors entering the UAE require an entry visa that needs to be arranged prior to arrival, with the exception of certain nationalities, which are: Andorra; Australia; Austria; Belgium; Brunei; Bulgaria; Canada; China; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; France; GCC countries; Germany; Greece; Holland; Hong Kong; Hungary: Iceland; Ireland; Italy; Japan; Latvia; Lithuania; Liechtenstein; Luxembourg; Malaysia; Malta; Monaco; Netherlands; New Zealand; Norway; Poland; Portugal; Romania; San Marino; Singapore; Slovenia, Slovakia, South Korea; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; UK; USA; Vatican City. Any of the above nationalities can procure your visa upon arrival from immigration. If you do not fall into one of the above nationalities, you will require a visa and a sponsor for your visit. Please be advised No Oman visa is required to visit Zighy Bay; you can visit on your UAE Tourist Visa. The Tourist Visa entitles its holder up to a 15 or 30-day stay and is non-renewable. You can arrange this Tourist Visa through your local UAE Consulate or Embassy. If you would like us to arrange your Tourist Visa, our colleagues at South Travels will be happy to assist. They will require: • Completed visa form • Copy of first and last page of your passport • Passport size photograph. • Tourist Visa processing charges: for up to 15 days is USD 150 per person; for up to 30-days is USD 232 per person Minimum of 7 (seven) working days are necessary for visa processing. An electronic visa will be provided via email; please print for provision at immigration upon arrival to Dubai International Airport. -

Part 3: Normal Faults and Extensional Tectonics

12.113 Structural Geology Part 3: Normal faults and extensional tectonics Fall 2005 Contents 1 Reading assignment 1 2 Growth strata 1 3 Models of extensional faults 2 3.1 Listric faults . 2 3.2 Planar, rotating fault arrays . 2 3.3 Stratigraphic signature of normal faults and extension . 2 3.4 Core complexes . 6 4 Slides 7 1 Reading assignment Read Chapter 5. 2 Growth strata Although not particular to normal faults, relative uplift and subsidence on either side of a surface breaking fault leads to predictable patterns of erosion and sedi mentation. Sediments will fill the available space created by slip on a fault. Not only do the characteristic patterns of stratal thickening or thinning tell you about the 1 Figure 1: Model for a simple, planar fault style of faulting, but by dating the sediments, you can tell the age of the fault (since sediments were deposited during faulting) as well as the slip rates on the fault. 3 Models of extensional faults The simplest model of a normal fault is a planar fault that does not change its dip with depth. Such a fault does not accommodate much extension. (Figure 1) 3.1 Listric faults A listric fault is a fault which shallows with depth. Compared to a simple planar model, such a fault accommodates a considerably greater amount of extension for the same amount of slip. Characteristics of listric faults are that, in order to maintain geometric compatibility, beds in the hanging wall have to rotate and dip towards the fault. Commonly, listric faults involve a number of en echelon faults that sole into a lowangle master detachment. -

The Jabal Akhdar Dome in the Oman Mountains: Evolution of a Dynamic Fracture System

n Gomez-Rivas, E., Bons, P.D., Koehn, D., Urai, J.L., Arndt, M., Virgo, S., Laurich, B., Zeeb, C., Stark, L., and Blum, P. (2014) The Jabal Akhdar Dome in the Oman Mountains: evolution of a dynamic fracture system. American Journal of Science, 314 (7). pp. 1104-1139. ISSN 0002- 9599 Copyright © 2014 American Journal of Science A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/94553/ Deposited on: 12 November 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 The Jabal Akhdar Dome in the Oman Mountains: evolution of a 2 dynamic fracture system 3 4 E. GOMEZ-RIVAS*, P. D. BONS*, D. KOEHN**, J. L. URAI***, M. ARNDT***, S. 5 VIRGO***, B. LAURICH***, C. ZEEB****, L. STARK* and P. BLUM**** 6 7 * Department of Geosciences, Eberhard Karls University Tübingen, Germany; enrique.gomez-rivas@uni- 8 tuebingen.de 9 ** School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom 10 *** Structural Geology, Tectonics and Geomechanics, RWTH Aachen University, Germany 11 **** Institute for Applied Geosciences (AGW), Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Germany 12 13 ABSTRACT. The Mesozoic succession of the Jabal Akhdar dome in the Oman Mountains 14 hosts complex networks of fractures and veins in carbonates, which are a clear example of 15 dynamic fracture opening and sealing in a highly overpressured system. -

Welcome to Anantara Al Jabal Al Akhdar Resort a Guide to Etiquette, Climate and Transportation

EXPERIENCE NEW HEIGHTS OF LUXURY WITH AUTHENTIC OMANI HOSPITALITY WELCOME TO ANANTARA AL JABAL AL AKHDAR RESORT A GUIDE TO ETIQUETTE, CLIMATE AND TRANSPORTATION ETIQUETTE As a general courtesy with respect to local customs, it is highly recommended to dress modestly whilst out and about in Oman. We suggest for guests to cover their shoulders and legs (from the knee up), and to avoid form fitting clothing. CLIMATE Al Jabal Al Akhdar is known for its Mediterranean climate. Temperatures drop during winter to below zero degrees Celsius with snow falling at times, and rise in the summer to 28 degrees Celsius. TRANSPORTATION Kindly be informed that you need a 4x4 vehicle to pass by the check point for Al Jabal Al Akhdar, along with your driving license and car registration papers. If you are not driving a 4x4 vehicle, you may park near the check point and request for us to arrange a luxury 4x4 transfer to the resort. Please contact us at tel +968 25218000 for more information. TOP 10 FUN THINGS TO DO IN AL JABAL AL AKHDAR 1. Kids Camping 2. Rock Climbing 3. Wadi of Waterfalls Hike 4. Via Ferrata Mountain Climbing 5. Stargazing 6. Cycling Tours 7. Three Village Adventure Treks 8. Sundown Journey Tour 9. Morning Yoga 10. Archery Lessons DIRECTIONS TO ANANTARA AL JABAL AL AKHDAR RESORT Seeb MUSCAT Muscat International Airport 15 15 Nizwa / Salalah Exit 15 Jabal Akhdar Hotel Samail 15 15 Jabal Akhdar Hotel FROM MUSCAT 172 KM / 2HR 15MIN Use the Northwest expressway out of Muscat heading towards Seeb, and turn off at the Nizwa/Salalah exit and continue following signs towards Izki / Nizwa. -

Al Alama Centre

ALAL AMANAALAMAALAMA CENTRECENTRECENTRE MUSCAT,MUSCAT, SULTANATESULTANATE OFOF OMANOMAN HH AA NN DD BB OO OO KK 0 OUR HISTORY – A UNIQUE LEGACY The name “Al Amana” is Arabic for “bearing trust,” which captures the spirit and legacy of over 115 years of service in Oman. The Centre is the child of the Gulf-wide mission of the Reformed Church in America that began in Oman in 1893. The mission‟s first efforts were in educational work by establishing a school in 1896 that eventually became a coeducational student body of 160 students. The school was closed in 1987 after ninety years of service to the community. The mission was active in many other endeavors, which included beginning a general hospital (the first in Oman), a maternity hospital, a unit for contagious diseases, and a bookshop. With the growth of these initiatives, by the 1950‟s the mission was the largest employer in the private sector in Oman. In the 1970‟s the hospitals were incorporated in the Ministry of Health, and the mission staff worked for the government to assist in the development of its healthcare infrastructure. The mission also established centers for Christian worship in Muscat and Muttrah. It is out of these centers that the contemporary church presence for the expatriate community Oman has grown, now occupying four campuses donated by His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said. After Oman discovered oil, having a newfound wealth with which to modernize, the mission's activities were either concluded or grew into independent initiatives. However, the desire to serve the people of Oman continued. -

Plate Tectonics

Plate Tectonics Plate Tectonics is a unifying theory that states that the Earth is composed of lithospheric crustal plates that move slowly, change size, and interact with one another. This theory was amalgamated from a variety of studies that began in the early 20th century and culminated in the 1960s. Early Players: Richard Oldham (1858-1936): discovered P Wave Shadow Zones Inge Lehmann (1888-1993): discovered the S Wave Shadow Zone, including the fact that the outer core is liquid Eduard Suess (1831-1914): published internal structure of the Earth, utilizing some of Oldham’s data Andrija Mohorovicic (1857-1936): discovered the seismic discontinuity between the crust and the mantle Beno Gutenberg (1889-1960): found the CMB to be at 2900 km The Great Synthesizer: Alfred Wagener (1880-1930) Book: The Origin of Continents and Oceans (1915) Found six major pieces of evidence the continents move, hence his theory is known as Continental Drift. (Figures 19.2-1911) 1) The shape of the continents: they fit together 2) Paleontological Evidence: found matching fossils on several continents a) Glossopteris: found in rocks of the same age on South America, South Africa, Australia, India and Antarctica b) Lystrosaurus: found in rocks of the same age on Africa, India, also some in Asia and Antarctica c) Mesosaurus: found in rocks of the same age on South America, South Africa d) Cynognathus: found in rocks of the same age on South America, South Africa 3) Glacial Evidence: the glaciers appear to originate from the modern-day oceans (which is impossible) 4) Structure and Rock Type: geologic features end on one continent and reappear on the other (South America and Africa) 5) Paleoclimate Zones: like today, the old Earth had climate zones. -

Before the Emirates: an Archaeological and Historical Account of Developments in the Region C

Before the Emirates: an Archaeological and Historical Account of Developments in the Region c. 5000 BC to 676 AD D.T. Potts Introduction In a little more than 40 years the territory of the former Trucial States and modern United Arab Emirates (UAE) has gone from being a blank on the archaeological map of Western Asia to being one of the most intensively studied regions in the entire area. The present chapter seeks to synthesize the data currently available which shed light on the lifestyles, industries and foreign relations of the earliest inhabitants of the UAE. Climate and Environment Within the confines of a relatively narrow area, the UAE straddles five different topographic zones. Moving from west to east, these are (1) the sandy Gulf coast and its intermittent sabkha; (2) the desert foreland; (3) the gravel plains of the interior; (4) the Hajar mountain range; and (5) the eastern mountain piedmont and coastal plain which represents the northern extension of the Batinah of Oman. Each of these zones is characterized by a wide range of exploitable natural resources (Table 1) capable of sustaining human groups practising a variety of different subsistence strategies, such as hunting, horticulture, agriculture and pastoralism. Tables 2–6 summarize the chronological distribution of those terrestrial faunal, avifaunal, floral, marine, and molluscan species which we know to have been exploited in antiquity, based on the study of faunal and botanical remains from excavated archaeological sites in the UAE. Unfortunately, at the time of writing the number of sites from which the inventories of faunal and botanical remains have been published remains minimal. -

Persian Gulf States, Old and New Co-Exist in Innovative and Intriguing Ways

PERsiAn OMAN, ABU DHABI, GulF QATAR AND DUBAI Aboard the Crystal Esprit CRUISE January 2–12, 2020 DUBAI FEATURING Trevor Marchand Emeritus Professor of Social Anthropology at SOAS, London DEAR TRAVELER, You are invited to join Archaeological Institute of America lecturer and host Trevor Marchand for this compelling cruise aboard the yacht-like, all-suite, 31-cabin Crystal Esprit. In the Persian Gulf states, old and new co-exist in innovative and intriguing ways. During this exploration of Dubai, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, and Oman you will visit the mosques, souks, educational institutions, and museums that reflect a fascinating juxtaposition of past and present that is unique to the Islamic world. Begin your exploration among the dazzling skyscrapers of Dubai, the business and cultural hub of the Middle East and home to some of the most stunning architectural masterpieces of the 20th and 21st centuries. Continue to Qatar, where visits to the old souq and the new Education City illustrate how dramatically change has come to the Gulf States. In the emirate of Abu Dhabi, museums, mosques, and Masdar City amaze with both their sheer grandeur and minute detail. Wrap up your journey with a cruise through the fjord-like waterways of Oman’s Musandam Peninsula and visits to some of the country’s culturally rich museums, mosques, and markets. For those who wish to further explore the region, optional pre- and post-cruise extensions in Dubai and Oman’s interior are also available. You will learn about the cultures, art, architecture, and history of this region on daily shore excursions and during an enriching onboard educational program with AIA lecturer Trevor Marchand and other onboard lecturers. -

Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S

Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy Updated May 19, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RS21534 SUMMARY RS21534 Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy May 19, 2021 The Sultanate of Oman has been a strategic partner of the United States since 1980, when it became the first Persian Gulf state to sign a formal accord permitting the U.S. military to use its Kenneth Katzman facilities. Oman has hosted U.S. forces during every U.S. military operation in the region since Specialist in Middle then, and it is a partner in U.S. efforts to counter terrorist groups and other regional threats. In Eastern Affairs January 2020, Oman’s longtime leader, Sultan Qaboos bin Sa’id Al Said, passed away and was succeeded by Haythim bin Tariq Al Said, a cousin selected by Oman’s royal family immediately upon Qaboos’s death. Sultan Haythim espouses policies similar to those of Qaboos and has not altered U.S.-Oman ties or Oman’s regional policies. During Qaboos’s reign (1970-2020), Oman generally avoided joining other countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates , Bahrain, Qatar, and Oman) in regional military interventions, instead seeking to mediate their resolution. Oman joined but did not contribute forces to the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State organization, nor did it arm groups fighting Syrian President Bashar Al Asad’s regime. It opposed the June 2017 Saudi/UAE- led isolation of Qatar and had urged resolution of that rift before its resolution in January 2021. -

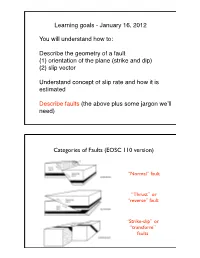

Describe the Geometry of a Fault (1) Orientation of the Plane (Strike and Dip) (2) Slip Vector

Learning goals - January 16, 2012 You will understand how to: Describe the geometry of a fault (1) orientation of the plane (strike and dip) (2) slip vector Understand concept of slip rate and how it is estimated Describe faults (the above plus some jargon weʼll need) Categories of Faults (EOSC 110 version) “Normal” fault “Thrust” or “reverse” fault “Strike-slip” or “transform” faults Two kinds of strike-slip faults Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) Stand with your feet on either side of the fault. Which side comes toward you when the fault slips? Another way to tell: stand on one side of the fault looking toward it. Which way does the block on the other side move? Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) 1992 M 7.4 Landers, California Earthquake rupture (SCEC) Describing the fault geometry: fault plane orientation How do you usually describe a plane (with lines)? In geology, we choose these two lines to be: • strike • dip strike dip • strike is the azimuth of the line where the fault plane intersects the horizontal plane. Measured clockwise from N. • dip is the angle with respect to the horizontal of the line of steepest descent (perpendic. to strike) (a ball would roll down it). strike “60°” dip “30° (to the SE)” Profile view, as often shown on block diagrams strike 30° “hanging wall” “footwall” 0° N Map view Profile view 90° W E 270° S 180° Strike? Dip? 45° 45° Map view Profile view Strike? Dip? 0° 135° Indicating direction of slip quantitatively: the slip vector footwall • let’s define the slip direction (vector) -

FMFRP 0-54 the Persian Gulf Region, a Climatological Study

FMFRP 0-54 The Persian Gulf Region, AClimatological Study U.S. MtrineCorps PCN1LiIJ0005LFII 111) DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY Headquarters United States Marine Corps Washington, DC 20380—0001 19 October 1990 FOREWORD 1. PURPOSE Fleet Marine Force Reference Publication 0-54, The Persian Gulf Region. A Climatological Study, provides information on the climate in the Persian Gulf region. 2. SCOPE While some of the technical information in this manual is of use mainly to meteorologists, much of the information is invaluable to anyone who wishes to predict the consequences of changes in the season or weather on military operations. 3. BACKGROUND a. Desert operations have much in common with operations in the other parts of the world. The unique aspects of desert operations stem primarily from deserts' heat and lack of moisture. While these two factors have significant consequences, most of the doctrine, tactics, techniques, and procedures used in operations in other parts of the world apply to desert operations. The challenge of desert operations is to adapt to a new environment. b. FMFRP 0-54 was originally published by the USAF Environmental Technical Applications Center in 1988. In August 1990, the manual was published as Operational Handbook 0-54. 4. SUPERSESSION Operational Handbook 0-54 The Persian Gulf. A Climatological Study; however, the texts of FMFRP 0—54 and OH 0-54 are identical and OH 0-54 will continue to be used until the stock is exhausted. 5. RECOMMENDATIONS This manual will not be revised. However, comments on the manual are welcomed and will be used in revising other manuals on desert warfare.