Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clothing List

Clothing List Name tapes optional Indelible marking on items is recommended 2 grey tees Logo (optional) 2 Purple tees Logo (optional) 6 t-shirts/polos/tanks 4 pair of jeans/ long pants 6 pair of shorts 2 sweatshirts, crew or hooded (Logo optional) 1 pair of sweatpants 2-3 Dresses or separates including a banquet dress 10 pairs of underwear 6 bras 1 set of warm sleep ware 1 bathrobe 2 sets of lightweight sleep ware 1-2 sport work- out tops and bottoms 1 pair of athletic sneakers 1 dress shoes ( sturdy not mules) 1 pair comfortable shoes 1 pair bedroom slippers Outerwear 3 sweaters 1 lightweight jacket/pullover/vest 1 heavy jacket 1 Long rain coat or poncho with hood or hat 1 pair rainy day waterproof shoes or boots Bed and Bath 2 blankets or 1 comforter and 1 blanket 2 fitted cot size sheets 2 standard twin top sheets 1 pillow 2 pillow cases 4 bath towels 2 wash cloths 1 shower organizer (grades 6-8 only) toothbrush, toothpaste, hairbrush, soap and shampoo 1 pair of shower sandals (grades 6-8 only) 1 laundry bag with NAME printed clearly Sports Classes Swimming 2 swim suits 1 Purple Freeze Frame Team Suit for Competitive Swim Team 1 swim cap 1 goggles 1 towel sunscreen, nose clip, ear plugs if required Tennis 2 tees with Belvoir logo for team players 1 visor or cap 1 tennis racket 1 pair of tennis sneakers Riding 1 riding helmet 1 pair of riding boots or heeled shoes 1 pair of riding jodhpurs, jeans or long pants Fitness 1 pair running shoes Outdoor Ed 1 sleeping bag 1 hiking boots or good shoes Dance Classes Ballet 3 leotards (one must -

Business Professional Dress Code

Business Professional Dress Code The way you dress can play a big role in your professional career. Part of the culture of a company is the dress code of its employees. Some companies prefer a business casual approach, while other companies require a business professional dress code. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR MEN Men should wear business suits if possible; however, blazers can be worn with dress slacks or nice khaki pants. Wearing a tie is a requirement for men in a business professional dress code. Sweaters worn with a shirt and tie are an option as well. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR WOMEN Women should wear business suits or skirt-and-blouse combinations. Women adhering to the business professional dress code can wear slacks, shirts and other formal combinations. Women dressing for a business professional dress code should try to be conservative. Revealing clothing should be avoided, and body art should be covered. Jewelry should be conservative and tasteful. COLORS AND FOOTWEAR When choosing color schemes for your business professional wardrobe, it's advisable to stay conservative. Wear "power" colors such as black, navy, dark gray and earth tones. Avoid bright colors that attract attention. Men should wear dark‐colored dress shoes. Women can wear heels or flats. Women should avoid open‐toe shoes and strapless shoes that expose the heel of the foot. GOOD HYGIENE Always practice good hygiene. For men adhering to a business professional dress code, this means good grooming habits. Facial hair should be either shaved off or well groomed. Clothing should be neat and always pressed. -

Lesson 12 Personal Appearance Kā Bong-Hāgn Phtial Khluon

Lesson 12 Personal Appearance karbgØajpÞal´xøÜn kā bong-hāgn phtial khluon This lesson will introduce you to: - One’s physical features (hair color, weight, height, etc.) - Articles of clothing - Colors - Description of a person’s physical appearance, including the clothing - Appropriate ways to ask about someone’s appearance. 1. Look at the pictures below and familiarize yourself with the new vocabulary. Listen to the descriptions of people’s appearances. Tall Short Heavy Thin Young Old Kpos Teap Tom Skom Kmeing Chas x¬s´ Tab ZM s¬m ekµg cas´ Short Long Blond Red Gray Klei Veing Ton deing Kro hom Bro peis xøI Evg Tg´Edg ®khm ®bep; 193 2. Look at the pictures below and listen to the descriptions of people’s appearances. This woman is young. This man is also young. Strei nis keu kmeing. Boros nis keu kmeing pong daer. RsþI en; KW ekµg. burs en; KW ekµgpgEdr. She is tall and thin. He has an average height and medium frame. Neang keu kposh houy skorm. Boros mean kom posh lmom houy meat lmom. nag KW x¬s´ ehIy s<m. burs man kMBs´ lµm ehIy maD lµm. Grammar Note: There are different usages of adjectives for describing people and things: For example: Humans: Things: tall long ‘x¬s´’ ‘Evg’ short ( short Tab’ ‘xøI’ thin thin ‘s<m’ ‘esþIg’ However, Cambodians don’t distinguish gender when using adjectives. 3. Look at the pictures below and familiarize yourself with the new vocabulary. Listen to the speaker and repeat as you follow along in the workbook. Hair: Blond Tong deing Tg´Edg Brown Tnout etñat Red Kro hom Rkhm 194 Gray Pro peh Rbep; Curly Rougn rYj Straight Trong Rtg´ 3a. -

Approximate Weight of Goods PARCL

PARCL Education center Approximate weight of goods When you make your offer to a shopper, you need to specify the shipping cost. Usually carrier’s shipping pricing depends on the weight of the items being shipped. We designed this table with approximate weight of various items to help you specify the shipping costs. You can use these numbers at your carrier’s website to calculate the shipping price for the particular destinations. MEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 70 - 100 Jacket 1000 - 1200 Sports shirt, T-shirt 220 - 300 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 UnderpantsShirt 70120 - -100 180 JacketWind-breaker 1000800 - -1200 1200 SportsBusiness shirt, suit T-shirt 2201200 - -300 1800 Coat,Autumn duster jacket 9001200 - -1500 1400 Sports suit 1000 - 1300 Winter jacket 1400 - 1800 Pants 600 - 700 Fur coat 3000 - 8000 Jeans 650 - 800 Hat 60 - 150 Shorts 250 - 350 Scarf 90 - 250 UnderpantsJersey 70450 - -100 600 JacketGloves 100080 - 140 - 1200 SportsHoodie shirt, T-shirt 220270 - 300400 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 WOMEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 15 - 30 Shorts 150 - 250 Bra 40 - 70 Skirt 200 - 300 Swimming suit 90 - 120 Sweater 300 - 400 Tube top 70 - 85 Hoodie 400 - 500 T-shirt 100 - 140 Jacket 230 - 400 Shirt 100 - 250 Coat 600 - 900 Dress 120 - 350 Wind-breaker 400 - 600 Evening dress 120 - 500 Autumn jacket 600 - 800 Wedding dress 800 - 2000 Winter jacket 800 - 1000 Business suit 800 - 950 Fur coat 3000 - 4000 Sports suit 650 - 750 Hat 60 - 120 Pants 300 - 400 Scarf 90 - 150 Leggings -

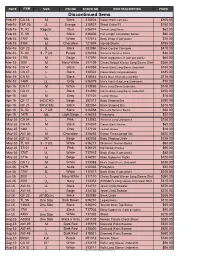

2017 Nefful Product Discontinued List

DATE ITEM SIZE COLOR STOCK NO. ITEM DESCRIPTION PRICE 2017 NeffulCO Product Discontinued List Discontinued Items Feb-16 CA 48 M Black 318026 Classic Black Camisole $105.00 Feb-16 DW 05 LL Orange 315937 Shawl Collar PJ $780.00 Feb-16 TL 52 Regular Blue 616074 Teviron Long Socks $62.00 Feb-16 TL 59 L Black 616406 Full Length Circulation Socks $90.00 Feb-16 1707 ML White 717014 Body Wrap (1 per pack) $70.00 Feb-16 3364 M Chocolate 121834 Hip-Up Shorts $155.00 Mar-16 QF 23 3L Black 382094 Black Control Camisole $410.00 Mar-16 TL 02 5 - 7 US Purple 616063 Women's Summer Socks $38.00 Mar-16 1705 M Beige 717091 Wrist supporters (1 pair per pack) $60.00 Mar-16 2001 M Navy-White 317109 Chess Striped Woven Long Sleeve Shirt $360.00 Mar-16 CA 41 M Black 314059 Classic Black Long-Sleeve Undershirt $150.00 Mar-16 CA 47 L Black 318024 Classic Black Long Underpants $185.00 Mar-16 CA 52 L Black 318044 Men's Black Short-Sleeved Shirt $178.00 Mar-16 1489 LL Gray 616079 Men's Tight-Fitting Long Underpants $70.00 Apr-16 CA 11 M White 313085 Men's Long-Sleeve Undershirt $148.00 Apr-16 CA 41 L Black 314060 Classic Black Long-Sleeve Undershirt $150.00 Apr-16 1461 M Gray 717101 Teviron Gloves $18.00 Apr-16 QF 11 36C(C80) Beige 382013 Body Shaping Bra $290.00 Apr-16 QF 21 38C(C85) Black 382064 Black Shaping Bra $315.00 Apr-16 TL 02 5 - 7 US Black 616058 Women's Summer Socks $38.00 Apr-16 1479 ML Light Beige 616033 Pantyhose $30.00 May-16 CA 04 L Pink 313082 Women's Long Underpants $150.00 May-16 CA 45 M Black 314067 Classic Black Panties $65.00 May-16 1461 L -

Clothing in France

CLOTHING IN FRANCE For their day-to-day activities, the French, both in the countryside and the cities, wear modern Western-style clothing. Perhaps the most typical item of clothing associated with the French is the black beret. It is still worn by some men, particularly in rural areas. The French are renowned for fashion design. Coco Chanel, Yves Saint-Laurent, Christian Dior, and Jean-Paul Gautier are all French fashion design houses whose creations are worn by people around the world. Traditional regional costumes are still worn at festivals and celebrations. In Alsace, women may be seen in white, lace-trimmed blouses and aprons decorated with colorful flowers. Women's costumes in Normandy include white, flared bonnets and dresses with wide, elbow-length sleeves. A traditional symbol of the region, the famous Alsatian headdress was abandoned after 1945. Today, this can only be admired during certain cultural and tourist events. Varying widely from one part of Alsace to another, the traditional costumes reflected the social standing and faith of their wearers. Consequently, Protestant women in the North would wear the colors of their choosing; where as Catholics from Kochersberg (to the northwest of Strasbourg) wore only ruby red. Some women would decorate the hems of their skirts with velvet ribbons. Others, particularly in the south, would wear printed cotton clothing, often made of silk for special occasions with paisley patterned designs. The aprons, worn everywhere throughout Alsace, were plain white. However, on Sundays it was not uncommon to see silk or satin aprons decorated with embroidery, and worn over skirts or dresses. -

Shulchan Arukh Amy Milligan Old Dominion University, [email protected]

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Women's Studies Faculty Publications Women’s Studies 2010 Shulchan Arukh Amy Milligan Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/womensstudies_fac_pubs Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Yiddish Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Milligan, Amy, "Shulchan Arukh" (2010). Women's Studies Faculty Publications. 10. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/womensstudies_fac_pubs/10 Original Publication Citation Milligan, A. (2010). Shulchan Arukh. In D. M. Fahey (Ed.), Milestone documents in world religions: Exploring traditions of faith through primary sources (Vol. 2, pp. 958-971). Dallas: Schlager Group:. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Women’s Studies at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spanish Jews taking refuge in the Atlas Mountains in the fifteenth century (Spanish Jews taking refuge in the Atlas Mountains, illustration by Michelet c.1900 (colour litho), Bombled, Louis (1862-1927) / Private Collection / Archives Charmet / The Bridgeman Art Library International) 958 Milestone Documents of World Religions Shulchan Arukh 1570 ca. “A person should dress differently than he does on weekdays so he will remember that it is the Sabbath.” Overview Arukh continues to serve as a guide in the fast-paced con- temporary world. The Shulchan Arukh, literally translated as “The Set Table,” is a compilation of Jew- Context ish legal codes. -

Career Center General Guidelines for BUSINESS CASUAL and BUSINESS FORMAL ATTIRE

Career Center General Guidelines for BUSINESS CASUAL and BUSINESS FORMAL ATTIRE Interviews still require business formal attire while other corporate meetings and events can be attended in business casual. Almost two thirds of workers today wear business casual clothes regularly to work. Here are some basic guidelines and website references to clarify the dress code when the corporate/company event you plan to attend requests that you achieve a certain look. Business Casual for Men • Basic business casual dress is generally considered a polo shirt/khaki/navy pant combo. • Dockers and a button down shirt kick the concept up a notch. The key to this look is wearing a shirt that has a collar. • Add a sports coat to achieve a dressy, casual look. • Shoes should be tie or loafer style but never tennis shoes, boots or beach sandals. • Belts, shoes and socks should compliment the outfit. Matching belts and shoes as a rule of thumb is complimentary. No white socks. • No short sleeve shirts with a tie, shirts with logos, wrinkled clothing or denim jeans. Business Casual for Women • Women should select pantsuits that coordinate in color or may opt for khaki/navy pants with a polo or long sleeve button blouse. • Skirts and dresses can also be considered casual dress worn with hose/stockings. If a skirt is worn, utilize a simple buttoned shirt or blouse. • Closed toe shoes should be worn. Never sandals. • Avoid any shirts with logos, flannel pullovers or any jean type or denim pants. Business Formal for Men and Women • For men, the standard look for business formal attire is dress slacks (not Dockers) with matching coat and white or blue shirt with coordinating tie. -

School Supplies

THURMONT PRIMARY SCHOOL SCHOOL SUPPLY LIST 2019 – 2020 Listed below are supplies that your child will use during the school year in the instructional program at each grade level. It is particularly helpful for our younger students if items could be labeled with their names prior to bringing them to school. We appreciate your support in providing these materials for your child, however, if you are unable to purchase any of these supplies, please contact the office and we will be happy to provide the items for your child. DONATIONS of the following items for class use throughout the year are appreciated: Tissues, Band-Aids, Ziploc bags – assorted sizes, crayons, pencil cap erasers, antibacterial pump soap, colored pencils, washable markers, bar pink erasers, EXPO fine point dry-erase markers (black only), 3 oz. paper or plastic bathroom cups (PK only), baby wipes (PK only) OPTIONAL for all grades: reusable water bottle, plastic or metal (no glass) with a push up top or straw top that seals lid tightly. No screw open cap bottles please. Please mark with student name. Pre-kindergarten Kindergarten Individual - label all supplies please Individual – label all supplies please: 1 regular size (not preschool/toddler) book 1 regular size book bag without wheels bag without wheels or toys 2 lined composition books Complete change of clothes in labeled Ziploc 1 red pocket folder with 3 prongs in middle bag (underpants, socks, shirt, pants or Complete change of clothes in labeled Ziploc dress) bag (underpants, socks, shirt, pants or 1 composition book (preferably unlined) dress) Community supplies our class will share: Community supplies our class will share: 4 large glue sticks 2 boxes of 24 crayons – Crayola 1 pack washable markers 2 packs EXPO skinny black dry-erase markers 2 packs EXPO black dry-erase markers 1 set #2 pencils, sharpened 4 large glue sticks Home – use these supplies at home: scissors Home – use these supplies at home: glue scissors crayons glue pencils crayons markers pencils old magazines, newspapers, etc. -

Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eoN - Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa University of Copenhagen Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Gaspa, Salvatore, "Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eN o-Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 3. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The Neo- Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa, University of Copenhagen In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. -

The Expectant Mother

`Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits Volume 4 • Issue 22 `Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita `All Piskei Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita are reviewed by Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita The Expectant Mother The time when a couple finds out that a child is on the way is a very happy time. Many different halachos apply to an expecting mother, along with many segulos. These items and many others will be discussed in this issue. אאייאיןןאיןן לללוולוו ללההקקלהקבבלהקבב""הה Davening for the Child בבעעווללממבעולמוובעולמוו The Mishnah in Mesechtas Berochos1 says one who davens to have a specific gender has davened an invalid tefilla. The Gemorah2 explains that this is only after forty days from when אאללאלאאאלאא דד'' the child was conceived. The first three days one should daven that the seed should not spoil. From the third day until the fortieth day one should daven for a boy. From forty days אאממוואמותתאמותת until three months one should daven that the child should be of normal shape. From three שששללשלל ההללככהלכהההלכהה בבללבבבלבדדבלבדד............ .54a .1 ((בבררככווברכותתברכותת חח...)).)) 60a. Refer to Rosh 9:17, Shulchan Aruch 230:1, Mishnah Berurah 230:1, Aruch Ha’shulchan 230:3 .2 The Expectant Mother | 1 months to six months that the fetus should survive. From six months to nine months one should daven that the child should come out healthy. The Elya Rabbah3 says one should daven that the child should be a G-D fearing person and a big ba’al middos. A woman who does not have any children should say the haftora of the first day of -

Sonoma County Clothing & Personal Care Resources

SONOMA COUNTY CLOTHING & PERSONAL CARE RESOURCES Note: Some services may have changed due to COVID-19, Please call to confirm hours and services available CLOTHING RECOURCES Friends in Sonoma Helping (FISH) – The Clothes Room “For clothing or household items” Location: 18330 Sonoma Highway Sonoma, CA 95476 Contact: (707) 996-0111 Website: http://www.friendsinsonomahelping.org Last Verified On: 01/25/2021 Catholic Charities of Santa Rosa – Homeless Services Center Goodwill – The Clothes Closet “Offers drop-in services such as showers, “Provides job seekers with interview- laundry, telephone access, mail service, as appropriate clothing and once employed, well as information and referrals to supportive continue to assist with building a work services and shelter.” wardrobe.” 600 Morgan Street Location: Location: 651 Yolanda Avenue Santa Rosa, CA 95402 Santa Rosa, CA 95404 (707) 525-0226 Contact: Contact: (707) 523-0550 http://www.srcharities.org Website: Website: http://goodwill.wp.iescentral.com/wp- Last Verified On: 01/25/2021 content/uploads/2020/07/The-Clothes- Bayside Santa Rosa – Open Closet Closet.pdf “Provide food and clothing to the people of Last Verified On: 01/25/2021 Sonoma County” Social Advocates for Youth (SAY) – Street Location: 3175 Sebastopol Road Outreach Program Santa Rosa, CA 95407 “Helping youth obtain ID’s, fill out employment Date/Time: Second Saturday of each month applications, get new clothes, find housing, and starting at 8 a.m. support them in meeting their educational Contact: (707) 528-8463 goals.” Website: Location: 1243 Ripley Street http://redwoodcovenant.org/outreach.html Santa Rosa, CA 95401 Last Verified On: 01/25/2021 Contact: (707) 544-3299 ext.