3: Transport in London and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Operator's Story Appendix

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: London’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from London Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in London. These notes are based upon 14 meetings between 6th-9th October 2015, plus one further meeting in January 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and TfL. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by TfL (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by TfL themselves and those expressed about their organisation. -

Investigation Into Reliability of the Jubilee Line

Investigation into Reliability: London Underground Jubilee Line An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science By Jack Arnis Agolli Marianna Bailey Errando Berwin Jayapurna Yiannis Kaparos Date: 26 April 2017 Report Submitted to: Malcolm Dobell CPC Project Services Professors Rosenstock and Hall-Phillips Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects. Abstract Metro systems are often faced with reliability issues; specifically pertaining to safety, accessibility, train punctuality, and stopping accuracy. The project goal was to assess the reliability of the London Underground’s Jubilee Line and the systems implemented during the Jubilee Line extension. The team achieved this by interviewing train drivers and Transport for London employees, surveying passengers, validating the stopping accuracy of the trains, measuring dwell times, observing accessibility and passenger behavior on platforms with Platform Edge Doors, and overall train performance patterns. ii Acknowledgements We would currently like to thank everyone who helped us complete this project. Specifically we would like to thank our sponsor Malcolm Dobell for his encouragement, expert advice, and enthusiasm throughout the course of the project. We would also like to thank our contacts at CPC Project Services, Gareth Davies and Mehmet Narin, for their constant support, advice, and resources provided during the project. -

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Thames Tideway Tunnel Interim Measures to Reduce Infraction Fines

Thames Tideway Tunnel Interim measures to reduce infraction fines. Working draft 5th February 2013 Report By Professor Chris Binnie MA, DIC, HonDEng, FREng, FICE, FCIWEM 2013 Brockwell, Wootton Courtenay, Minehead Somerset TA24 8RN Tideway tunnel interim scheme 28 8 12 1 Executive summary Any long term solution to the Thames Tideway CSO problems would take many years to implement, so I propose interim measures to much improve the Tideway within two to three years. The European Commission has taken out infraction proceedings against the UK for slow implementation of the UWWTD. The European Court of Justice has found against the UK on the Thames Tideway. Thus it is likely that infraction fines will be imposed. My information is that these could be substantial, based on the current tunnel completion date of 2023 as high as Euros 2.0 bn. I am advised that they would be based partly on the “Environmental impact of non-compliance “. A reduction of one point out of five points on the “environmental impact of non-compliance” or “member state conduct”might save as much as Euro 200 million, about £160m. Standards for ecology, aesthetics, and health impact have been set for the Tideway. The current STW improvements, and the Lee Tunnel would reduce the spill volume from 39Mm3/year to about 18Mm3/years, a long way to achieving the dissolved oxygen standards. However the Thames Tideway Tunnel will not be operational until about 2023. Thus interim measures could be implemented to reduce “the environmental impact of non-compliance” until the tunnel is operational. The object of these interim measures would not be to meet the standards set for the Tideway but to mitigate the environmental impact to the extent that the substantial fines would be reduced. -

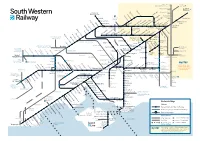

Download Network

Milton Keynes, London Birmingham and the North Victoria Watford Junction London Brentford Waterloo Syon Lane Windsor & Shepherd’s Bush Eton Riverside Isleworth Hounslow Kew Bridge Kensington (Olympia) Datchet Heathrow Chiswick Vauxhall Airport Virginia Water Sunnymeads Egham Barnes Bridge Queenstown Wraysbury Road Longcross Sunningdale Whitton TwickenhamSt. MargaretsRichmondNorth Sheen BarnesPutneyWandsworthTown Clapham Junction Staines Ashford Feltham Mortlake Wimbledon Martins Heron Strawberry Earlsfield Ascot Hill Croydon Tramlink Raynes Park Bracknell Winnersh Triangle Wokingham SheppertonUpper HallifordSunbury Kempton HamptonPark Fulwell Teddington Hampton KingstonWick Norbiton New Oxford, Birmingham Winnersh and the North Hampton Court Malden Thames Ditton Berrylands Chertsey Surbiton Malden Motspur Reading to Gatwick Airport Chessington Earley Bagshot Esher TolworthManor Park Hersham Crowthorne Addlestone Walton-on- Bath, Bristol, South Wales Reading Thames North and the West Country Camberley Hinchley Worcester Beckenham Oldfield Park Wood Park Junction South Wales, Keynsham Trowbridge Byfleet & Bradford- Westbury Brookwood Birmingham Bath Spaon-Avon Newbury Sandhurst New Haw Weybridge Stoneleigh and the North Reading West Frimley Elmers End Claygate Farnborough Chessington Ewell West Byfleet South New Bristol Mortimer Blackwater West Woking West East Addington Temple Meads Bramley (Main) Oxshott Croydon Croydon Frome Epsom Taunton, Farnborough North Exeter and the Warminster Worplesdon West Country Bristol Airport Bruton Templecombe -

Su103 Box Hill from Westhumble

0 Miles 1 2 su103 Box Hill from Westhumble 0 Kilometres 1 2 3 The Burford Bridge roundabout is on the The walk shown is for guidance only and should With thanks to Dean Woodrow A24 between Dorking and Leatherhead not be attempted without suitable maps. Details 3 Go W (right) up the road for 200m and then 5 Go NW (left) across the grass to reach a SE on a signed path that descends through a road and then W (left) on the road to go N Distance: 11km (7 miles) field, a wood and a 2nd field to reach a road. pass the car park and NT Shop. At a '1.5T' Total Ascent: 340m (1115ft) Go E (left) on the road past the remains of road sign go NW (left) past Box Hill Fort to Time: 31/2 hrs Grade: 4 Westhumble Chapel to reach a crossroads. Go descend a bridleway to a fork. Go NW (left) to Maps: OS Landranger® 187 SE on Adlers Lane and continue SE at a join a 2nd path that descends across the or OS Explorer Map™ 146 junction. At a crossing path go S (right) on a grass. After 200m fork (W) left on a faint path Start/Finish: Burford Bridge Car Park footpath (signed 'Dorking') to reach a 2nd to descend more steeply. Continue through a A24 S of Mickleham, Surrey crossing path - The North Downs Way (NDW). small wood to reach a road opposite the car 1 Grid Ref: TQ172521 (1 /2 km) park and the start. (2km) Sat Nav: N51.2560 W0.3227 4 Go E (left) on the NDW to pass under the railway and then cross the A24. -

Niche Innovation Dynamics and the Urban Mobility Transition the Case of Dockless Bike-Sharing in London

Niche innovation dynamics and the urban mobility transition The case of dockless bike-sharing in London Russell Cannon Urban Studies Master’s Programme (Two-Year) 30 Credits VT2019 Supervisor: Désirée Nilsson 1 Abstract This thesis seeks to provide a detailed understanding of the introduction of dockless bike-sharing to London. As part of a wave of new smart and shared mobility services that are aiming to transform the way people move around cities, this emerging form of transport has created disruptions in London since its launch in 2017. This study aims analyse to what extent dockless bike-sharing aligns or conflicts with the aims and objectives of local authorities governing public space in London. In doing so, it also aims to reveal insights into transformations in contemporary mobility by exploring the dynamics of niche innovations within socio-technical transitions, thus contributing to knowledge in the field of transition studies. To do this, a qualitative case study methodology was employed using document analysis and interviews with four stakeholders integrally involved in the case study, representing both public authorities and a private sector dockless bike-sharing operator, Mobike. The findings demonstrate that dockless bike-sharing is well aligned with the city’s explicit objectives to reduce car dependency and encourage active travel. It has particular potential to make cycling more accessible by bringing bike-sharing to parts of the city that do not have access to the pre-existing, docked bike-sharing scheme, operated by the central transport authority, Transport for London. Despite this, dockless bike-sharing, as a niche innovation, has struggled to break into the existing urban mobility regime. -

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

71 Villiers Avenue, Surbiton, Kingston Upon Thames Kt5 8Aw

RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY FOR SALE Indicative Visualisation 71 VILLIERS AVENUE, SURBITON, KINGSTON UPON THAMES KT5 8AW SUMMARY DESCRIPTION • 3-bedroom detached house occupying a site of circa 0.11 acres The existing property comprises 3-bedroom house across 2-storeys, positioned on a broadly rectangular site of circa 0.11 acres. • Planning permission for a 3-storey building comprising 6 residential units (2 x 1 bed, 2 x 2 bed and 2 x 3 bed) extending to The house is bounded by residential properties. approximately 4,715ft2 • Appeal lodged for 8 residential unit scheme (2 x studio, 2 x 1 bed, 2 x 2 bed and 2 x 3 bed) totalling 5,285ft2 • Offers are invited in excess of £1,250,000 for the freehold interest, subject to a £150,000 uplift if the Appeal scheme is successful LOCATION The property is located on Villiers Avenue, within the Royal Borough of Kingston Upon Thames. The surrounding area comprises mainly high-quality residential properties. There are a number of shops and commercial amenities located on nearby Victoria Road in Surbiton. The nearest station is Surbiton which is circa 0.5 miles from the property providing National Rail services into London Waterloo in 30 minutes. www.kingsbury-consultants.co.uk Ordnance Survey © Crown Copyright 2019. All Rights Reserved. Licence number 100022432 Plotted Scale - 1:1250. Paper Size - A4 RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY FOR SALE DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL TENURE Planning permission has been approved at appeal (ref: 18/16587/ The property will be sold Freehold with vacant possession on FUL) for the demolition of the existing building and erection of a new completion. -

Swan Lane Pier, 1 Swan Lane London Ec4r 3Tn Pdf 6 Mb

Committee: Date: Planning and Transportation 6 October 2020 Subject: Public Swan Lane Pier 1 Swan Lane London EC4R 3TN Erection of a new pier within the River Thames at Swan Lane, to comprise a refurbished landside access platform; new canting brow and pontoon; dredging and filling of river bed; repair and reinstatement of campshed and riverbank; replacement of mooring pile and installation of additional mooring pile. Ward: Bridge And Bridge Without For Decision Registered No: 19/00116/FULL Registered on: 28 February 2019 Conservation Area: Listed Building: No Summary The application relates to the redevelopment of Swan Lane Pier. The pier is not in use which currently comprises just the dolphins and has been in its current state since 2012 when the regalia boat was removed from the pier. The pier is located and accessed via Swan Lane, which is south of Lower Thames Street. Planning permission is sought for: Erection of a new pier within the River Thames at Swan Lane, to comprise a refurbished landside access platform; new canting brow and pontoon; dredging and filling of river bed; repair and reinstatement of campshed and riverbank; replacement of mooring pile and installation of additional mooring pile. 836 objections have been received from residents and local occupiers regarding the proposed development. The objections have raised concerns regarding the adverse impact on residential amenity, noise and air pollution from the use of the pier from charter vessels, namely the Ocean Diva. Further concerns relate to the emergency and national safety of vessels, antisocial behaviour, visual amenity and protected views, lack of transparency, highway and walkway congestion and that the proposal is contrary to policy. -

Up to 30,585 Sq Ft of Exceptional Office Space Manor Royal Crawley Rh10

up to 30,585 sq ft of exceptional office space MANOR ROYAL CRAWLEY RH10 9PY Palladian comprises a SQ FT SQ M Ground Floor self-contained office Reception 367 34.1 building Offices 15,657 1,454.6 Arranged over ground and first floors providing 30,585 sq ft (2,841 sq m) of Grade A office First Floor accommodation. Offices 14,127 1,312.4 The property has undergone comprehensive Terrace 434 40.3 refurbishment, providing occupiers with highly specified and efficient space, which benefits from Total 30,585 2,841.4 high quality, contemporary finishes. Floors can be The property has been measured in accordance with sub-divided to accommodate requirements from the RICS International Property Measurement Standards approximately 6,000 sq ft. (IPMS3) 1st Edition, dated May 2015. N N RECEPTION MALE MALE FEMALE WC WC WC LIFT LIFT FEMALE WC DIS’ MEZZANINE CLEANER’S SHOWER WC CLEANERS OFFICE OFFICE TERRACE OFFICE DIS’ WC/SHOWER FEMALE FEMALE SHOWER WC WC ROOF MALE ELEC. ACCESS MALE WC SWITCH WC ROOM STAIRS/LOBBY Ground Floor First Floor Dotted line demonstrates indicative half floor split. Specification • All new VRF air conditioning and BMS system • New suspended ceilings and LED lighting • Raised access floor with new carpet installed • New contemporary reception area • Passenger lift • New cycle store and shower facilities • New outdoor amenity area with seating • Electric car charging points • Excellent on-site car parking (1:267 sq ft) for 115 cars • Excellent security with access control and building CCTV • Fully DDA compliant • Full building generator -

London Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Delivery Plan Supported by the Mayor’S Electric Vehicle Infrastructure June 2019 Taskforce Contents

London electric vehicle infrastructure delivery plan Supported by The Mayor’s Electric Vehicle Infrastructure June 2019 Taskforce Contents Mayor’s foreword 4 The delivery plan 4.1 Challenges Executive summary 4.2 Guiding principles 1 Introduction and aims 4.3 Defining what is needed 1.1 Introduction 5 What can we do to make 1.2 Supporting policies this happen? towards zero emission 5.1 Facilitate smoother installation 1.3 What London is already and match supply with demand doing to support EV charging infrastructure 5.2 Reduce energy barriers 1.4 The Mayor’s EV 5.3 Share knowledge and maximise Infrastructure Taskforce potential of legislation 2 The current situation 5.4 Charter of commitments in London Glossary 2.1 Electric vehicles 2.2 Charging infrastructure Appendix A – Detailed modelling assumptions and approach 2.3 User experience Appendix B – Principal author: Zero 3 User needs Carbon Futures 3.1 Understanding charging needs 3.2 Modelling potential demand to 2025 we must move away from petrol and There’s no shying away from the fact diesel cars, and towards electric and that expanding our public charge hydrogen vehicles. Bringing about this points will be challenging. London’s sea change won’t be easy, but with land is always in high demand, our the right political will and ambition I’m streets are often narrow and we have confident we can pull it off. to work with 35 different planning authorities. But we know there is a I’m proud that London is one of real appetite to cut harmful emissions the first major cities in the world and propel London towards a greener to publish a detailed and future.