Wittgenstein, Language and Chess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

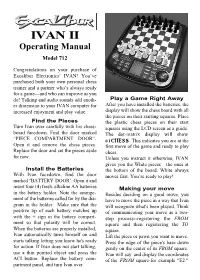

IVAN II Operating Manual Model 712

IVAN II Operating Manual Model 712 Congratulations on your purchase of Excalibur Electronics’ IVAN! You’ve purchased both your own personal chess trainer and a partner who’s always ready for a game—and who can improve as you do! Talking and audio sounds add anoth- Play a Game Right Away er dimension to your IVAN computer for After you have installed the batteries, the increased enjoyment and play value. display will show the chess board with all the pieces on their starting squares. Place Find the Pieces the plastic chess pieces on their start Turn Ivan over carefully with his chess- squares using the LCD screen as a guide. board facedown. Find the door marked The dot-matrix display will show “PIECE COMPARTMENT DOOR”. 01CHESS. This indicates you are at the Open it and remove the chess pieces. first move of the game and ready to play Replace the door and set the pieces aside chess. for now. Unless you instruct it otherwise, IVAN gives you the White pieces—the ones at Install the Batteries the bottom of the board. White always With Ivan facedown, find the door moves first. You’re ready to play! marked “BATTERY DOOR’. Open it and insert four (4) fresh, alkaline AA batteries Making your move in the battery holder. Note the arrange- Besides deciding on a good move, you ment of the batteries called for by the dia- have to move the piece in a way that Ivan gram in the holder. Make sure that the will recognize what's been played. Think positive tip of each battery matches up of communicating your move as a two- with the + sign in the battery compart- step process--registering the FROM ment so that polarity will be correct. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

Finding Checkmate in N Moves in Chess Using Backtracking And

Finding Checkmate in N moves in Chess using Backtracking and Depth Limited Search Algorithm Moch. Nafkhan Alzamzami 13518132 Informatics Engineering School of Electrical Engineering and Informatics Institute Technology of Bandung, Jalan Ganesha 10 Bandung [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—There have been many checkmate potentials that has pieces of a dark color. There are rules about how pieces players seem to miss. Players have been training for finding move, and about taking the opponent's pieces off the board. checkmates through chess checkmate puzzles. Such problems can The player with white pieces always makes the first move.[4] be solved using a simple depth-limited search and backtracking Because of this, White has a small advantage, and wins more algorithm with legal moves as the searching paths. often than Black in tournament games.[5][6] Keywords—chess; checkmate; depth-limited search; Chess is played on a square board divided into eight rows backtracking; graph; of squares called ranks and eight columns called files, with a dark square in each player's lower left corner.[8] This is I. INTRODUCTION altogether 64 squares. The colors of the squares are laid out in There have been many checkmate potentials that players a checker (chequer) pattern in light and dark squares. To make seem to miss. Players have been training for finding speaking and writing about chess easy, each square has a checkmates through chess checkmate puzzles. Such problems name. Each rank has a number from 1 to 8, and each file a can be solved using a simple depth-limited search and letter from a to h. -

CHESS How to Play Chess: Rules and Basics

CHESS By Mind Games How to Play Chess: Rules and Basics It's never too late to learn how to play chess - the most popular game in the world! Learning the rules of chess is easy: Step 1. How to Setup the Chessboard At the beginning of the game the chessboard is laid out so that each player has the white (or light) color square in the bottom right-hand side. The chess pieces are then arranged the same way each time. The second row (or rank) is filled with pawns. The rooks go in the corners, then the knights next to them, followed by the bishops, and finally the queen, who always goes on her own matching color (white queen on white, black queen on black), and the king on the remaining square. Step 2. How the Chess Pieces Move Each of the 6 different kinds of pieces moves differently. Pieces cannot move through other pieces (though the knight can jump over other pieces), and can never move onto a square with one of their own pieces. However, they can be moved to take the place of an opponent's piece which is then captured. Pieces are generally moved into positions where they can capture other pieces (by landing on their square and then replacing them), defend their own pieces in case of capture, or control important squares in the game. How to Move the King in Chess The king is the most important piece, but is one of the weakest. The king can only move one square in any direction - up, down, to the sides, and diagonally. -

Instructions and Solutions Your Goal: Capture the Chess Pieces Until Only One Piece Remains on the Challenge Card

STRATEGIC SKILL BUILDING GAME Instructions and Solutions Your Goal: Capture the chess pieces until only one piece remains on the challenge card. STRATEGIC SKILL BUILDING GAME ThinkFun’s Brain Fitness games are designed as a fun way to help you exercise your brain. The 80 challenges will stretch your mental muscles and strengthen speed, focus, and memory. We recommend Setup: that you start with the beginner level and work through the challenges progressively. Just 15 minutes of play a day will reduce stress and Choose a challenge card and cover the chess piece icons with the provide a good brain workout. You’re on your way to a healthier brain! matching chess pieces. Chess has long been known as the world’s deepest thinking game. To Play: ® Solitaire Chess combines the rules of traditional chess and peg 1. Move the chess pieces according to the movement rules solitaire to bring you a delightful and vigorous brain workout! It’s okay (pages 6-7)*. Each move must result in a captured piece. if you’ve never played chess before, this is an inviting way to learn some chess playing strategies or build the skills that you already have! 2. If you are left with two or more pieces on the challenge card, reset and try again. Includes: 3. When there is only one piece remaining–YOU WIN! • 1 Booklet with 80 Challenges • 10 Chess Pieces Note: If you are stuck, reference the solutions on pages 8 to 11. • 1 Booklet with Instructions and Solutions *Movements are the same as in standard chess. -

Rules for Chess

Rules for Chess Object of the Chess Game It's rather simple; there are two players with one player having 16 black or dark color chess pieces and the other player having 16 white or light color chess pieces. The chess players move on a square chessboard made up of 64 individual squares consisting of 32 dark squares and 32 light squares. Each chess piece has a defined starting point or square with the dark chess pieces aligned on one side of the board and the light pieces on the other. There are 6 different types of chess pieces, each with it's own unique method to move on the chessboard. The chess pieces are used to both attack and defend from attack, against the other players chessmen. Each player has one chess piece called the king. The ultimate objective of the game is to capture the opponents king. Having said this, the king will never actually be captured. When either sides king is trapped to where it cannot move without being taken, it's called "checkmate" or the shortened version "mate". At this point, the game is over. The object of playing chess is really quite simple, but mastering this game of chess is a totally different story. Chess Board Setup Now that you have a basic concept for the object of the chess game, the next step is to get the the chessboard and chess pieces setup according to the rules of playing chess. Lets start with the chess pieces. The 16 chess pieces are made up of 1 King, 1 queen, 2 bishops, 2 knights, 2 rooks, and 8 pawns. -

Chess Sets from 1700 to the Introduction of the Staunton Design (1849)

Page 1 of 7 The Conventional Chess Sets from 1700 to the introduction of the Staunton Design (1849) Chesmayne Chess History Time Lines: 1500's . 1600's . 1700's . 1800's . 1900's Today, the Staunton design, named after a Chess Master in England, but actually developed by and produced by John Jaques of London in 1849, is now the standard design for chess pieces. Prior to that, a number of Conventional styles of turned chess sets preceded the introduction of the Staunton Design in 1849. These pieces were designed for play using simplified or abstract shapes and made of more inexpensive materials than more ornate displays sets. Some of these various styles were named after either the Coffee House/ Chess Clubs in London and Paris, and other European cities where they were used; or the skilled turners who created them. Along with these Conventional Playing Sets, there were also a variety of Representational Sets - the latter tended to be more for display than play. The original chess sets from the East were highly abstracted pieces. Early Western sets were carved figures such as the Lewis Chess men or those of Charlemagne's time. In the Middle Ages, Chess was a game mainly for the Nobility and Clergy. They could afford expensive ornate sets. During the Renaissance, it was still mainly a game for the households of kings such as Philip II of Spain or Henry the 8th; and the Queens, such as Catherine De Medici, or Elizabeth I. A revolution in Chess play in the West was the development of the powerful Chess Queen. -

Chess Rules- the Ultimate Guide for Beginners by GM Igor Smirnov

Chess Rules- The Ultimate Guide for Beginners By GM Igor Smirnov A PUBLICATION OF ABOUT THE AUTHOR Grandmaster Igor Smirnov Igor Smirnov is a chess Grandmaster, coach, and holder of a Master’s degree in psychology. He’s the founder of the “Remote Chess Academy” company that has helped thousands of students worldwide to improve their results. GM Smirnov has developed lots of chess video lessons, articles, webinars and training courses, including the famous courses “The Grandmaster’s Secrets”, “The Grandmaster’s Positional Understanding”, and “Calculate Till Mate”. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.Evolution of chess rules 8.Movement of the pieces 2.The chessboard 9.Special moves 3.Symbols of chessmen 10.Promoted Pawn 4.Arrangements of pieces 11.Check and Checkmate 5.Nature and objectives 12.Draw 6.Naming of squares 13.Values of chess pieces 7.Colour classification 14.Three stages of chess 3 Chess is the most intelligent game ever invented. It has a lot of things that are similar to life. It trains you to use all your resources to the maximum extent. Learning basic chess rules will help you build a strong foundation in chess. Many students do not have clear picture on these rules at their beginning stages. That is why I decided to help beginners with basic chess rules. Chess teaches you administration and to extract work from your subordinates. It is a battle between two monarchs. The king manages the troops. He plans the operation and executes it. 1 Evolution of chess rules The rules of chess have evolved much over the centuries, from the early chess-like games played in India in the 6th century. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

The Knights Handbook

The Knights Handbook Miha Canˇculaˇ The Knights Handbook 2 Contents 1 Introduction 6 2 How to play 7 2.1 Objective . .7 2.2 Starting the Game . .7 2.3 The Chess Server Dialog . .9 2.4 Playing the Game . 11 3 Game Rules, Strategies and Tips 12 3.1 Standard Rules . 12 3.2 Chessboard . 12 3.2.1 Board Layout . 12 3.2.2 Initial Setup . 13 3.3 Piece Movement . 14 3.3.1 Moving and Capturing . 14 3.3.2 Pawn . 15 3.3.3 Bishop . 16 3.3.4 Rook . 17 3.3.5 Knight . 18 3.3.6 Queen . 18 3.3.7 King . 19 3.4 Special Moves . 20 3.4.1 En Passant . 20 3.4.2 Castling . 21 3.4.3 Pawn Promotion . 22 3.5 Game Endings . 23 3.5.1 Checkmate . 23 3.5.2 Resign . 23 3.5.3 Draw . 23 3.5.4 Stalemate . 24 3.5.5 Time . 24 3.6 Time Controls . 24 The Knights Handbook 4 Markers 25 5 Game Configuration 27 5.1 General . 27 5.2 Computer Engines . 28 5.3 Accessibility . 28 5.4 Themes . 28 6 Credits and License 29 4 Abstract This documentation describes the game of Knights version 2.5.0 The Knights Handbook Chapter 1 Introduction GAMETYPE: Board NUMBER OF POSSIBLE PLAYERS: One or two Knights is a chess game. As a player, your goal is to defeat your opponent by checkmating their king. 6 The Knights Handbook Chapter 2 How to play 2.1 Objective Moving your pieces, capture your opponent’s pieces until your opponent’s king is under attack and they have no move to stop the attack - called ‘checkmate’. -

Staunton Chess Set - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos

Staunton Chess Set - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos Staunton Chess Set Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos [email protected] Culture is the social use of human intelligence Gabriel García Márquez Contents: Introduction. 1. ORIGIN OF STAUNTON CHESS SET. 1.1. Novelty of the Registered Design. 1.2. Authorship and Place of Origin. 1.3. Importance of the Name. 1.4. Signature Guarantee. 2. OFFICIAL PIECES. 3. INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE. 3.1. Concept. 3.2. Reality and Formality. 3.3. Potential Advantages. 4. CHARACTERISTICS OF STAUNTON CHESS SET 4.1. Form and Function. 4.2. Special Features. 5. CURRENT SITUATION. Appendix: Brief list of major museums, private collections, and shops in Internet Classic Staunton Chess Set INTRODUCTION. As surprising as this may seem, not all the chess sets have been designed to play, hence, we find: 1 Staunton Chess Set - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Fernando Raventos - Functional pieces, designed to play, and - Ornamental pieces, designed to decorate (1) This article focuses on the best known functional pieces, called Staunton, which are widely accepted by casual and professionals players around the world. The Staunton chessmen were created in London in 1849, during the Victorian Era, over 160 years ago. They are masterpieces of functionality and elegance, so they have become the unique and unmistakable classic chess game pieces. Many players cannot imagine the game with other pieces. In 1924, these pieces were selected as the official set by the World Chess Federation; presently, for about 600 million players in over 120 countries, Stauton pieces are the choice of set. -

Chess Notation

Rock Canyon Chess Club Chess Notation: If you would like to study chess from our handouts and from chess books, knowing about chess notation would be very helpful. The following is a brief overview of how the “algebraic” chess notation system works. Each square on the board has a coordinate: Files on the chess board are indicated by small letters from “a” to “h” and rows (or ranks) are indicated by numbers from “1" to “8" as in the graphic below, so putting a letter and a number together gives you a specific square on the board. So at the beginning of the game if you look on square “d8" you should find Black’s Queen and on square “e1" you should find White’s King. Moves are written in pairs with white’s move first followed by black’s move. The first pair of moves would be written after the number “1.” and so forth. The capital letter indicates the chess piece that moves (see below). If there is no capital letter then it is a Pawn that moves. The letter and number that follows give the file and row that the piece moves to. Most games start with a Pawn move like “e4" which means whites King Pawn moves out two squares, often followed by Black moving its King Pawn to block white’s Pawn, in this case, “e5," so notation for these first moves would look like this: “1. e4 e5" If a piece is captured by a move, then an “x” is placed between the letter for the chess piece and the square that it moves to capturing the piece.