Limited Geographic Variation in the Vocalizations of a Neotropical Furnariid, Synallaxis Albescens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systematic Relationships and Biogeography of the Tracheophone Suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes)

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 499–512 www.academicpress.com Systematic relationships and biogeography of the tracheophone suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes) Martin Irestedt,a,b,* Jon Fjeldsaa,c Ulf S. Johansson,a,b and Per G.P. Ericsona a Department of Vertebrate Zoology and Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Department of Zoology, University of Stockholm, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden c Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark Received 29 August 2001; received in revised form 17 January 2002 Abstract Based on their highly specialized ‘‘tracheophone’’ syrinx, the avian families Furnariidae (ovenbirds), Dendrocolaptidae (woodcreepers), Formicariidae (ground antbirds), Thamnophilidae (typical antbirds), Rhinocryptidae (tapaculos), and Conop- ophagidae (gnateaters) have long been recognized to constitute a monophyletic group of suboscine passerines. However, the monophyly of these families have been contested and their interrelationships are poorly understood, and this constrains the pos- sibilities for interpreting adaptive tendencies in this very diverse group. In this study we present a higher-level phylogeny and classification for the tracheophone birds based on phylogenetic analyses of sequence data obtained from 32 ingroup taxa. Both mitochondrial (cytochrome b) and nuclear genes (c-myc, RAG-1, and myoglobin) have been sequenced, and more than 3000 bp were subjected to parsimony and maximum-likelihood analyses. The phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial and nuclear genes were compared and found to be very similar. The results from the analysis of the combined dataset (all genes, but with transitions at third codon positions in the cytochrome b excluded) partly corroborate previous phylogenetic hypotheses, but several novel arrangements were also suggested. -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

Evolution of the Ovenbird-Woodcreeper Assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Б/ Major Shifts in Nest Architecture and Adaptive Radiatio

JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY 37: 260Á/272, 2006 Evolution of the ovenbird-woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) / major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation Á Martin Irestedt, Jon Fjeldsa˚ and Per G. P. Ericson Irestedt, M., Fjeldsa˚, J. and Ericson, P. G. P. 2006. Evolution of the ovenbird- woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Á/ major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation. Á/ J. Avian Biol. 37: 260Á/272 The Neotropical ovenbirds (Furnariidae) form an extraordinary morphologically and ecologically diverse passerine radiation, which includes many examples of species that are superficially similar to other passerine birds as a resulting from their adaptations to similar lifestyles. The ovenbirds further exhibits a truly remarkable variation in nest types, arguably approaching that found in the entire passerine clade. Herein we present a genus-level phylogeny of ovenbirds based on both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA including a more complete taxon sampling than in previous molecular studies of the group. The phylogenetic results are in good agreement with earlier molecular studies of ovenbirds, and supports the suggestion that Geositta and Sclerurus form the sister clade to both core-ovenbirds and woodcreepers. Within the core-ovenbirds several relationships that are incongruent with traditional classifications are suggested. Among other things, the philydorine ovenbirds are found to be non-monophyletic. The mapping of principal nesting strategies onto the molecular phylogeny suggests cavity nesting to be plesiomorphic within the ovenbirdÁ/woodcreeper radiation. It is also suggested that the shift from cavity nesting to building vegetative nests is likely to have happened at least three times during the evolution of the group. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of the Nest Architecture of Neotropical Ovenbirds (Furnariidae)

The Auk 116(4):891-911, 1999 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE NEST ARCHITECTURE OF NEOTROPICAL OVENBIRDS (FURNARIIDAE) KRZYSZTOF ZYSKOWSKI • AND RICHARD O. PRUM NaturalHistory Museum and Department of Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas,Lawrence, Kansas66045, USA ABSTRACT.--Wereviewed the tremendousarchitectural diversity of ovenbird(Furnari- idae) nestsbased on literature,museum collections, and new field observations.With few exceptions,furnariids exhibited low intraspecificvariation for the nestcharacters hypothe- sized,with the majorityof variationbeing hierarchicallydistributed among taxa. We hy- pothesizednest homologies for 168species in 41 genera(ca. 70% of all speciesand genera) and codedthem as 24 derivedcharacters. Forty-eight most-parsimonious trees (41 steps,CI = 0.98, RC = 0.97) resultedfrom a parsimonyanalysis of the equallyweighted characters using PAUP,with the Dendrocolaptidaeand Formicarioideaas successiveoutgroups. The strict-consensustopology based on thesetrees contained 15 cladesrepresenting both tra- ditionaltaxa and novelphylogenetic groupings. Comparisons with the outgroupsdemon- stratethat cavitynesting is plesiomorphicto the furnariids.In the two lineageswhere the primitivecavity nest has been lost, novel nest structures have evolved to enclosethe nest contents:the clayoven of Furnariusand the domedvegetative nest of the synallaxineclade. Althoughour phylogenetichypothesis should be consideredas a heuristicprediction to be testedsubsequently by additionalcharacter evidence, this first cladisticanalysis -

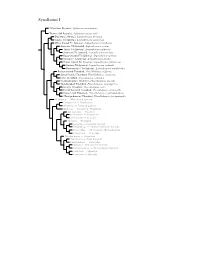

Synallaxini Species Tree

Synallaxini I ?Masafuera Rayadito, Aphrastura masafuerae Thorn-tailed Rayadito, Aphrastura spinicauda Des Murs’s Wiretail, Leptasthenura desmurii Tawny Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura yanacensis White-browed Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura xenothorax Araucaria Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura setaria Tufted Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura platensis Striolated Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striolata Rusty-crowned Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura pileata Streaked Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striata Brown-capped Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura fuliginiceps Andean Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura andicola Plain-mantled Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura aegithaloides Rufous-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus rufifrons Streak-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticeps Little Thornbird, Phacellodomus sibilatrix Chestnut-backed Thornbird, Phacellodomus dorsalis Spot-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus maculipectus Greater Thornbird, Phacellodomus ruber Freckle-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticollis Orange-eyed Thornbird, Phacellodomus erythrophthalmus ?Orange-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus ferrugineigula Hellmayrea — White-tailed Spinetail Coryphistera — Brushrunner Anumbius — Firewood-gatherer Asthenes — Canasteros, Thistletails Acrobatornis — Graveteiro Metopothrix — Plushcrown Xenerpestes — Graytails Siptornis — Prickletail Roraimia — Roraiman Barbtail Thripophaga — Speckled Spinetail, Softtails Limnoctites — ST Spinetail, SB Reedhaunter Cranioleuca — Spinetails Pseudasthenes — Canasteros Spartonoica — Wren-Spinetail Pseudoseisura — Cacholotes Mazaria – White-bellied -

Notes on the Distribution, Behaviour and First Description of the Nest Of

Cotinga 16 Notes on the distribution, behaviour and first description of the nest of Russet-bellied Spinetail Synallaxis zimmeri Irma Franke and Letty Salinas Cotinga 16 (2001): 90–93 El coliespina de pecho canela Synallaxis zimmeri es un ave endémica peruana conocida de tres localidades de la Cordillera Negra en el Perú central (09°27'S–09°53'S). Entre 1985 y 1988 fue encontrada en cuatro bosques nublados secos, ampliándose marcadamente el rango de distribución de la especie (07°42'S–10°03'S). En el bosque de Noqno (10°03'S 77°40'W, 2850 m), dpto. de Ancash, se encontró una población bastante numerosa de este coliespina y tres nidos, uno de ellos con pichones. El nido ocupado estaba ubicado a 4.2 m de altura entre ramas de Sebastiana obtusifolia y Myrcianthes quinqueloba. El nido es construido de ramitas espinosas entrelazadas y consta de tres partes. La primera es casi globular, de 26 cm de diámetro y contiene la cámara principal. La segunda parte es una extensión lateral de 20 cm de longitud y 8 cm de diámetro, formando el túnel de ingreso. La tercera, de 18 cm de diámetro, es una estructura globular construida de ramitas más gruesas entrelazadas con menor cuidado. La base de la cámara principal está acolchada con restos de hojas, principalmente nervaduras. Se realizaron observaciones del comportamiento de la hembra en las cercanías del nido durante un día. En el contenido de ocho estómagos se encontró que en promedio el 70 % del volumen consistía de insectos, de los cuales 28% eran insectos alados. -

CHESTNUT-THROATED SPINETAIL Synallaxis Cherriei K12

CHESTNUT-THROATED SPINETAIL Synallaxis cherriei K12 This little-known spinetail occurs in undergrowth in humid forest between 200 and 1,070 m at a handful of localities scattered across Brazil (six), Colombia (one), Ecuador (one) and Peru (four), and may be suffering from habitat loss. Whilst at one site it was only found in bamboo thickets inside at tall forest, which may partly explain its patchy distribution, competition from congeners also evidently plays a part. DISTRIBUTION The Chestnut-throated Spinetail occurs disjunctly in six areas of Brazil (nominate cherriei), with equally disjunct populations of the race napoensis (including the synonymized saturata of Carriker 1934) scattered through the foothills of the Andes in south-eastern Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. Given the breadth of this range, however, it is inevitable that many more localities will eventually be discovered. Brazil Localities for the species are as follows: Rondônia Barão de Melgaço, rio Ji-paraná, where the type-specimen was collected in March 1914 (Cherrie 1916, Gyldenstolpe 1930), this locality (previously part of Mato Grosso) being indicated as at 300 m (Paynter and Traylor 1991); Mato Grosso Alto Floresta, where a population was found in October 1989 (TAP); rio do Cágado, 250 m, 15°20’S 59°25’W, August 1987 and/or January 1988 (Willis and Oniki 1990, whence also coordinates); Pará 52 km south-south-west of Altamira on the east bank of the lower rio Xingu, 3°39’S 52°22’W, August/September 1986 (Graves and Zusi 1990, whence coordinates); in and adjacent to the Serra dos Carajás, namely at “Manganês” in the Serra Norte; and also at Gorotire, 7°40’S 51°15’W, near São Felix do Xingu, mid-1980s (Oren and da Silva 1987, whence coordinates). -

PINTURA CROMOSSÔMICA MULTIDIRECIONAL NO GENOMA DE Synallaxis Frontalis (PASSERIFORMES, FURNARIIDAE)

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PAMPA VANUSA LILIAN CAMARGO DE LIMA PINTURA CROMOSSÔMICA MULTIDIRECIONAL NO GENOMA DE Synallaxis frontalis (PASSERIFORMES, FURNARIIDAE) SÃO GABRIEL 2017 VANUSA LILIAN CAMARGO DE LIMA PINTURA CROMOSSÔMICA MULTIDIRECIONAL NO GENOMA DE SYNALLAXIS FRONTALIS (PASSERIFORMES, FURNARIIDAE) Dissertação apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto sensu em Ciências Biológicas da Universidade Federal do Pampa, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências Biológicas. Orientadora: Dra. Analía Del Valle Garnero SÃO GABRIEL 2017 Ficha catalográfica elaborada automaticamente com os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a) através do Módulo de Biblioteca do Sistema GURI (Gestão Unificada de Recursos Institucionais) . 732p LIMA, VANUSA LILIAN CAMARGO DE LIMA PINTURA CROMOSSÔMICA MULTIDIRECIONAL NO GENOMA DE Synallaxis frontalis (PASSERIFORMES, FURNARIIDAE) / VANUSA LILIAN CAMARGO DE LIMA LIMA. 44 p. Dissertação(Mestrado)-- Universidade Federal do Pampa, MESTRADO EM CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS, 2017. "Orientação: Analía Del Valle Garnero". 1. Aves. 2. Passeriformes. 3. cariótipo. 4. número diploide. 5. rearranjos intracromossômicos. I. Título. VANUSA LILIAN CAMARGO DE LIMA PINTURA CROMOSSÔMICA MULTIDIRECIONAL NO GENOMA DE Synallaxis frontalis (PASSERIFORMES, FURNARIIDAE) Dissertação apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto sensu em Ciências Biológicas da Universidade Federal do Pampa, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências Biológicas. Dissertação defendida e aprovada em: 24,março -

Multidirectional Chromosome Painting in Synallaxis Frontalis (Passeriformes, Furnariidae) Reveals High Chromosomal Reorganization, Involving Fissions and Inversions

COMPARATIVE A peer-reviewed open-access journal CompCytogen 12(1): 97–110High (2018) chromosomal reorganization in Synallaxis frontalis 971 doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v12i1.22344 RESEARCH ARTICLE Cytogenetics http://compcytogen.pensoft.net International Journal of Plant & Animal Cytogenetics, Karyosystematics, and Molecular Systematics Multidirectional chromosome painting in Synallaxis frontalis (Passeriformes, Furnariidae) reveals high chromosomal reorganization, involving fissions and inversions Rafael Kretschmer1, Vanusa Lilian Camargo de Lima2, Marcelo Santos de Souza2, Alice Lemos Costa3, Patricia C. M. O’Brien4, Malcolm A. Ferguson-Smith4, Edivaldo Herculano Corrêa de Oliveira5,6, Ricardo José Gunski2, Analía Del Valle Garnero2 1 Programa de Pós-graduação em Genética e Biologia Molecular, PPGBM, Universidade Federal do Rio Gran- de do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, RS, Brazil 2 Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências Biológicas, PPCGCB, Universidade Federal do Pampa, São Gabriel, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 3 Graduação em Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Pampa, São Gabriel, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 4 Cambridge Resource Centre for Comparative Genomics, Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ES, UK 5 Faculdade de Ciências Naturais, Instituto de Ciências Exatas e Naturais, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, Pará, Brazil 6 Laboratório de Cultura de Tecidos e Citogenética, SA- MAM, Instituto Evandro Chagas, Ananindeua, Brazil Corresponding author: Rafael Kretschmer ([email protected]) Academic editor: A. Barabanov | Received 17 November 2017 | Accepted 15 February 2018 | Published 13 March 2018 http://zoobank.org/C379B8F3-45B9-455E-9009-AC6E06A2B667 Citation: Kretschmer R, de Lima VLC, de Souza MS, Costa AL, O’Brien PCM, Ferguson-Smith MA, de Oliveira EHC, Gunski RJ, Garnero ADV (2018) Multidirectional chromosome painting in Synallaxis frontalis (Passeriformes, Furnariidae) reveals high chromosomal reorganization, involving fissions and inversions. -

Synallaxis Stictothorax Group (Aves: Passeriformes: Furnariidae): Synallaxis Chinchipensis Chapman, 1925 As a Valid Species, with a Lectotype Designation

70 (3): 319 – 331 © Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, 2020. 2020 Alpha taxonomy of Synallaxis stictothorax group (Aves: Passeriformes: Furnariidae): Synallaxis chinchipensis Chapman, 1925 as a valid species, with a lectotype designation Renata Stopiglia 1, 2, 3,*, Flávio A. Bockmann 3, 4, Claydson P. de Assis 2 & Marcos A. Raposo 2 1 Museu de História Natural do Ceará Prof. Dias da Rocha, Centro de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade Estadual do Ceará, Av. Dr. Silas Mun- guba, 1700, Campus Itaperi, 60741 – 000, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil — 2 Setor de Ornitologia, Departamento de Vertebrados, Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista, s/n, 20940 – 040 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil — 3 Laboratório de Ictiologia de Ribeirão Preto, Departamento de Biologia, FFCLRP, Universidade de São Paulo, Av. dos Bandeirantes 3900, 14040 – 901 Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil — 4 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Comparada, FFCLRP, Universidade de São Paulo, Av. dos Bandeirantes 3900, 14040 – 901 Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil — * Corresponding author; email: [email protected] Submitted July 10, 2019. Accepted July 6, 2020. Published online at www.senckenberg.de/vertebrate-zoology on August 7, 2020. Published in print on Q3/2020. Editor in charge: Martin Päckert Abstract The Synallaxis stictothorax group comprises poorly understood South American Furnariidae. This paper aims to present the morphological and nomenclatural aspects of this group, re-describing its valid species and to propose a fresh nomenclatural treatment for group members. Our analysis corroborated the specifc status of the disputed taxon Synallaxis chinchipensis and refuted the diagnostic characteristics of the subspecies Synallaxis stictothorax maculata. Following the recommendations of the Code, a lectotype was designated to the nominal species Synallaxis hypochondriaca. -

Panama's Canopy Tower and El Valle's Canopy Lodge

FIELD REPORT – Panama’s Canopy Tower and El Valle’s Canopy Lodge January 4-16, 2019 Orange-bellied Trogon © Ruthie Stearns Blue Cotinga © Dave Taliaferro Geoffroy’s Tamarin © Don Pendleton Ocellated Antbird © Carlos Bethancourt White-tipped Sicklebill © Jeri Langham Prepared by Jeri M. Langham VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DR., AUSTIN, TX 78746 Phone: 512-328-5221 or 800-328-8368 / Fax: 512-328-2919 [email protected] / www.ventbird.com Myriads of magazine articles have touted Panama’s incredible Canopy Tower, a former U.S. military radar tower transformed by Raúl Arias de Para when the U.S. relinquished control of the Panama Canal Zone. It sits atop 900-foot Semaphore Hill overlooking Soberania National Park. While its rooms are rather spartan, the food is Panama’s Canopy Tower © Ruthie Stearns excellent and the opportunity to view birds at dawn from the 360º rooftop Observation Deck above the treetops is outstanding. Twenty minutes away is the start of the famous Pipeline Road, possibly one of the best birding roads in Central and South America. From our base, daily birding outings are made to various locations in Central Panama, which vary from the primary forest around the tower, to huge mudflats near Panama City and, finally, to cool Cerro Azul and Cerro Jefe forest. An enticing example of what awaits visitors to this marvelous birding paradise can be found in excerpts taken from the Journal I write during every tour and later e- mail to participants. These are taken from my 17-page, January 2019 Journal. On our first day at Canopy Tower, with 5 of the 8 participants having arrived, we were touring the Observation Deck on top of Canopy Tower when Ruthie looked up and called my attention to a bird flying in our direction...it was a Black Hawk-Eagle! I called down to others on the floor below and we watched it disappear into the distant clouds. -

Ecology and Conservation of Neotropical-Nearctic Migratory

ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF NEOTROPICAL-NEARCTIC MIGRATORY BIRDS AND MIXED-SPECIES FLOCKS IN THE ANDES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gabriel J. Colorado, M.S. Environmental and Natural Resources Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor Amanda D. Rodewald, Adviser Professor Elizabeth Marschall Professor Paul Rodewald Copyright by Gabriel J. Colorado 2011 ABSTRACT The tropical Andes are widely recognized as one of the world´s great centers of biodiversity. High levels of both species richness and endemism coupled with one of the greatest rates of deforestation among tropical forests have made the Andes a major focal point of international conservation concern. In the face of current and projected rates of deforestation and habitat degradation of Andean forests, persistent large gaps in our understanding of ecological responses to anthropogenic disturbances limit our ability to effectively conserve biodiversity in the region. My dissertation focused on ecology and conservation of two poorly known components of Andean forest bird communities, mixed-species flocks and overwintering Neotropical-Nearctic migratory birds. Specifically, I (1) examined assembly patterns of mixed-species avian flocks, (2) evaluated the sensitivity of mixed-species flocks and Neotropical-Nearctic migratory birds to deforestation and structural changes in habitat, and (3) identified potential physiological