Science Fiction, Ecological Futures, and the Topography of Fritz Lang's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ein Deutsches Nibelungen-Triptychon. Die Nibelungenfilme Und Der Deutschen Not

Jörg Hackfurth (Gießen) Ein deutsches Nibelungen-Triptychon. Die Nibelungenfilme und der Deutschen Not 1. Einleitung In From Caligari to Hitler formuliert der Soziologe Siegfried Kracauer die These, daß „mittels einer Analyse der deutschen Filme tiefenpsychologi- sche Dispositionen, wie sie in Deutschland von 1918 bis 1933 herrschten, aufzudecken sind: Dispositionen, die den Lauf der Ereignisse zu jener Zeit beeinflussen und mit denen in der Zeit nach Hitler zu rechnen sein wird".1 Kracauers analytische Methode beruht auf einigen Prämissen, die hier noch einmal in ihrem originalen Wortlaut wiedergegeben werden sollen: „Die Filme einer Nation reflektieren ihre Mentalität unvermittelter als an- dere künstlerische Medien, und das aus zwei Gründen: Erstens sind Filme niemals das Produkt eines Individuums. [...] Da jeder Filmproduktionsstab eine Mischung heterogener Interessen und Neigungen verkörpert, tendiert die Teamarbeit auf diesem Gebiet dazu, willkürliche Handhabung des Filmmaterials auszuschließen und individuelle Eigenheiten zugunsten jener zu unterdrücken, die vielen Leuten gemeinsam sind. Zweitens richten sich Filme an die anonyme Menge und sprechen sie an. Von populären Filmen [...] ist daher anzunehmen, daß sie herrschende Massenbedürfnisse befrie- digen“2 Daraus resultiert ein Mechanismus, der sowohl in Hollywood als auch in Deutschland Geltung hat: „Hollywood kann es sich nicht leisten, Sponta- neität auf Seiten des Publikums zu ignorieren. Allgemeine Unzufriedenheit zeigt sich in rückläufigen Kasseneinnahmen, und die Filmindustrie, für die Profitinteresse eine Existenzfrage ist, muß sich so weit wie möglich den Veränderungen des geistigen Klimas anpassen".3 Ferner gilt: „Was die Filme reflektieren, sind weniger explizite Überzeu- gungen als psychologische Dispositionen – jene Tiefenschichten der Kol- lektivmentalität, die sich mehr oder weniger unterhalb der Bewußtseins- dimension erstrecken. -

Xx:2 Dr. Mabuse 1933

January 19, 2010: XX:2 DAS TESTAMENT DES DR. MABUSE/THE TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE 1933 (122 minutes) Directed by Fritz Lang Written by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou Produced by Fritz Lanz and Seymour Nebenzal Original music by Hans Erdmann Cinematography by Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner Edited by Conrad von Molo and Lothar Wolff Art direction by Emil Hasler and Karll Vollbrecht Rudolf Klein-Rogge...Dr. Mabuse Gustav Diessl...Thomas Kent Rudolf Schündler...Hardy Oskar Höcker...Bredow Theo Lingen...Karetzky Camilla Spira...Juwelen-Anna Paul Henckels...Lithographraoger Otto Wernicke...Kriminalkomissar Lohmann / Commissioner Lohmann Theodor Loos...Dr. Kramm Hadrian Maria Netto...Nicolai Griforiew Paul Bernd...Erpresser / Blackmailer Henry Pleß...Bulle Adolf E. Licho...Dr. Hauser Oscar Beregi Sr....Prof. Dr. Baum (as Oscar Beregi) Wera Liessem...Lilli FRITZ LANG (5 December 1890, Vienna, Austria—2 August 1976,Beverly Hills, Los Angeles) directed 47 films, from Halbblut (Half-caste) in 1919 to Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse (The Thousand Eye of Dr. Mabuse) in 1960. Some of the others were Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), The Big Heat (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Rancho Notorious (1952), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Scarlet Street (1945). The Woman in the Window (1944), Ministry of Fear (1944), Western Union (1941), The Return of Frank James (1940), Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Mabuse's Testament, There's a good deal of Lang material on line at the British Film The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse, 1933), M (1931), Metropolis Institute web site: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/lang/. -

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

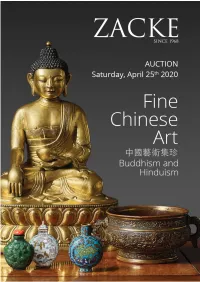

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

German Films

IP THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 11 WEST 53 STREET. NEW YORK 19. N. Y. TILIFHONI: CIICLI S-8f00 No. lUl FOR RELEASE: Sunday, December 8, 1957 FISCHINGER AND FRITZ LANG FILMS AT MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Another abstract film by Oskar Fischinger, Studie No. 11, and Fritz Lang's The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse (Das Testament des Mr. Mabuse) will be the 5 and 5:30 daily showings December 8 - 11 at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street. It is the current program in the series "Past and Present: A Selection of German Films, 1896 - 1957." Studie No. 11 (1932), abstract forms set to a minuet by Mozart, is an early experiment in the long sequence of "absolute films" still being made by Fischinger. Constructed under an esthetic disipline which regards people, settings and plot as extraneous, pattern, space, motion and rhythm are the only elements involved. A melodrama of a madman's plot to conquer the world through terrorism, The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse (1933) was the last film made by Fritz Lang in Germany. It was immediately banned by the Nazis. Lang, long considered a master in the treatment of psychological aberrations (M, Metropolis, Fury) said of Dr. Mabuse: "This film was made as an allegory, to show Hitler's processes of terrorism. Slo gans and doctrines of the Third Reich have been put into the mouths of criminals in the film..Thus I hoped to expose the masked Nazi theory of the necessity to de liberately destroy everything which is precious to a people so that they would lose all-.faith in the institutions and ideals of the State. -

From Iron Age Myth to Idealized National Landscape: Human-Nature Relationships and Environmental Racism in Fritz Lang’S Die Nibelungen

FROM IRON AGE MYTH TO IDEALIZED NATIONAL LANDSCAPE: HUMAN-NATURE RELATIONSHIPS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM IN FRITZ LANG’S DIE NIBELUNGEN Susan Power Bratton Whitworth College Abstract From the Iron Age to the modern period, authors have repeatedly restructured the ecomythology of the Siegfried saga. Fritz Lang’s Weimar lm production (released in 1924-1925) of Die Nibelungen presents an ascendant humanist Siegfried, who dom- inates over nature in his dragon slaying. Lang removes the strong family relation- ships typical of earlier versions, and portrays Siegfried as a son of the German landscape rather than of an aristocratic, human lineage. Unlike The Saga of the Volsungs, which casts the dwarf Andvari as a shape-shifting sh, and thereby indis- tinguishable from productive, living nature, both Richard Wagner and Lang create dwarves who live in subterranean or inorganic habitats, and use environmental ideals to convey anti-Semitic images, including negative contrasts between Jewish stereo- types and healthy or organic nature. Lang’s Siegfried is a technocrat, who, rather than receiving a magic sword from mystic sources, begins the lm by fashioning his own. Admired by Adolf Hitler, Die Nibelungen idealizes the material and the organic in a way that allows the modern “hero” to romanticize himself and, with- out the aid of deities, to become superhuman. Introduction As one of the great gures of Weimar German cinema, Fritz Lang directed an astonishing variety of lms, ranging from the thriller, M, to the urban critique, Metropolis. 1 Of all Lang’s silent lms, his two part interpretation of Das Nibelungenlied: Siegfried’s Tod, lmed in 1922, and Kriemhilds Rache, lmed in 1923,2 had the greatest impression on National Socialist leaders, including Adolf Hitler. -

Heng-Moduleawk7-Metropolis.Pdf

Phone: (02) 8007 6824 DUX Email: [email protected] Web: dc.edu.au 2018 HIGHER SCHOOL CERTIFICATE COURSE MATERIALS HSC English Advanced Module A: Metropolis Term 1 – Week 7 Name ………………………………………………………. Class day and time ………………………………………… Teacher name ……………………………………………... HSC English Advanced - Module A: Metropolis Term 1 – Week 7 1 DUX Term 1 – Week 7 – Theory • Film Analysis • Homework FILM ANALYSIS SEGMENT SIX (THE MACHINE-MAN) After discovering the workers' clandestine meeting, Freder's controlling, glacial father conspires with mad scientist Rotwang to create an evil, robotic Maria duplicate, in order to manipulate his workers and preach riot and rebellion. Fredersen could then use force against his rebellious workers that would be interpreted as justified, causing their self-destruction and elimination. Ultimately, robots would be capable of replacing the human worker, but for the time being, the robot would first put a stop to their revolutionary activities led by the good Maria: "Rotwang, give the Machine-Man the likeness of that girl. I shall sow discord between them and her! I shall destroy their belief in this woman --!" After Joh Fredersen leaves to return above ground, Rotwang predicts doom for Joh's son, knowing that he will be the workers' mediator against his own father: "You fool! Now you will lose the one remaining thing you have from Hel - your son!" Rotwang comes out of hiding, and confronts Maria, who is now alone deep in the catacombs (with open graves and skeletal remains surrounding her). He pursues her - in the expressionistic scene, he chases her with the beam of light from his bright flashlight, then corners her, and captures her when she cannot escape at a dead-end. -

La Reproducción De Valores Culturales En El Anime Japonés: Análisis De La Industria Cultural Japonesa

Facultad de Comunicación y Diseño Licenciatura en Ciencias de la Comunicación Tesis monográfica La reproducción de valores culturales en el Anime Japonés: análisis de la Industria Cultural Japonesa. Caso de estudio: STUDIO GHIBLI. Alumnos: Juan Martín García - L.U. 1105928 [email protected] 01163214019 Federico Peowich – L.U. 1106196 [email protected] 01133740407 Director de la carrera: Lic. José Crettaz Tutora: Lic. Romina Casas 1 Abstract La presente tesis monográfica pretende analizar y detallar las marcas y operaciones que construyen el concepto cultura japonesa dentro del animé de Studio Ghibli. Ghibli es un estudio de trayectoria mundial que produjo películas muy conocidas que utilizamos para el análisis: El viaje de Chihiro, La princesa Mononoke y Mi vecino Totoro. Hayao Miyazaki es el responsable de presentar un tipo de animé diferente al de robots o Samuráis. El principal objetivo es dilucidar de qué manera se representa la cultura japonesa en este particular anime. El análisis nos permite identificar elementos de construcción, así como obtener como producto final una idea de aquello que Miyazaki quiere que veamos o conozcamos de Japón. Palabras clave: animé, cultura, religión, sintoísmo, Japón, naturaleza, representación, análisis discursivo, construcción, representación. 2 Índice Problema ………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Marco de referencia ………………………………………………………………….... 7 Objetivos ………………………………………………………………………………… 11 Hipótesis …………………………………………………………………….................. 11 Marco teórico …………………………………………………………………………… 12 Marco metodológico …………………………………………………………………... 20 Capítulo 1: El Animé 1.0: Historia y evolución del animé ……………………………………………. 22 1.1 Primeros Pasos …………………………………………………………….. 22 1.2 Toei Doga …………………………………………………………………… 26 1.3 Studio Ghibli ………………………………………………………………… 30 1.4 Década de los 90 y 00´ (Madhouse y Production IG) ………………….. 31 Capítulo 2: El animé de Studio Ghibli. 2.0: Origen de Studio Ghibli ……………………………………………………. -

Cinema 2: the Time-Image

m The Time-Image Gilles Deleuze Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Caleta M IN University of Minnesota Press HE so Minneapolis fA t \1.1 \ \ I U III , L 1\) 1/ ES I /%~ ~ ' . 1 9 -08- 2000 ) kOTUPHA\'-\t. r'Y'f . ~ Copyrigh t © ~1989 The A't1tl ----resP-- First published as Cinema 2, L1111age-temps Copyright © 1985 by Les Editions de Minuit, Paris. ,5eJ\ Published by the University of Minnesota Press III Third Avenue South, Suite 290, Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 f'tJ Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 1'::>55 Fifth printing 1997 :])'''::''531 ~ Library of Congress Number 85-28898 ISBN 0-8166-1676-0 (v. 2) \ ~~.6 ISBN 0-8166-1677-9 (pbk.; v. 2) IJ" 2. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or othenvise, ,vithout the prior written permission of the publisher. The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. Contents Preface to the English Edition Xl Translators'Introduction XV Chapter 1 Beyond the movement-image 1 How is neo-realism defined? - Optical and sound situations, in contrast to sensory-motor situations: Rossellini, De Sica - Opsigns and sonsigns; objectivism subjectivism, real-imaginary - The new wave: Godard and Rivette - Tactisigns (Bresson) 2 Ozu, the inventor of pure optical and sound images Everyday banality - Empty spaces and stilllifes - Time as unchanging form 13 3 The intolerable and clairvoyance - From cliches to the image - Beyond movement: not merely opsigns and sonsigns, but chronosigns, lectosigns, noosigns - The example of Antonioni 18 Chapter 2 ~ecaPitulation of images and szgns 1 Cinema, semiology and language - Objects and images 25 2 Pure semiotics: Peirce and the system of images and signs - The movement-image, signaletic material and non-linguistic features of expression (the internal monologue). -

Animated Dialogues, 2007 29

Animation Studies – Animated Dialogues, 2007 Michael Broderick Superflat Eschatology Renewal and Religion in anime “For at least some of the Superflat people [...] there is a kind of traumatic solipsism, even an apocalyptic one, that underlies the contemporary art world as they see it.” THOMAS LOOSER, 2006 “Perhaps one of the most striking features of anime is its fascination with the theme of apocalypse.” SUSAN NAPIER, 2005 “For Murakami, images of nuclear destruction that abound in anime (or in a lineage of anime), together with the monsters born of atomic radiation (Godzilla), express the experience of a generation of Japanese men of being little boys in relation to American power.” THOMAS LAMARRE, 2006 As anime scholar Susan Napier and critics Looser and Lamarre suggest, apocalypse is a major thematic predisposition of this genre, both as a mode of national cinema and as contemporary art practice. Many commentators (e.g. Helen McCarthy, Antonia Levi) on anime have foregrounded the ‘apocalyptic’ nature of Japanese animation, often uncritically, deploying the term to connote annihilation, chaos and mass destruction, or a nihilistic aesthetic expression. But which apocalypse is being invoked here? The linear, monotheistic apocalypse of Islam, Judaism, Zoroastra or Christianity (with it’s premillennial and postmillennial schools)? Do they encompass the cyclical eschatologies of Buddhism or Shinto or Confucianism? Or are they cultural hybrids combining multiple narratives of finitude? To date, Susan Napier’s work (2005, 2007) is the most sophisticated examination of the trans- cultural manifestation of the Judeo-Christian theological and narrative tradition in anime, yet even her framing remains limited by discounting a number of trajectories apocalypse dictates.1 However, there are other possibilities. -

Ell 1E5 570 ' CS 20 5 4,96;

. MC0111117 VESUI17 Ell 1E5 570 ' CS 20 5 4,96; AUTHOR McLean, Ardrew M. TITLE . ,A,Shakespeare: Annotated BibliographiesendAeaiaGuide 1 47 for Teachers. .. INSTIT.UTION. NIttional Council of T.eachers of English, Urbana, ..Ill. .PUB DATE- 80 , NOTE. 282p. AVAILABLe FROM Nationkl Coun dil of Teachers,of Englishc 1111 anyon pa., Urbana, II 61.801 (Stock No. 43776, $8.50 member, . , $9.50 nor-memberl' , EDRS PRICE i MF011PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Biblioal7aphies: *Audiovisual Aids;'*Dramt; +English Irstruction: Higher Education; 4 *InstrUctioiral Materials: Literary Criticism; Literature: SecondaryPd uc a t i on . IDENTIFIERS *Shakespeare (Williaml 1 ABSTRACT The purpose of this annotated b'iblibigraphy,is to identify. resou'rces fjor the variety of approaches tliat teachers of courses in Shakespeare might use. Entries in the first part of the book lear with teaching Shakespeare. in secondary schools and in college, teaching Shakespeare as- ..nerf crmance,- and teaching , Shakespeare with other authora. Entries in the second part deal with criticism of Shakespearear films. Discussions of the filming of Shakespeare and of teachi1g Shakespeare on, film are followed by discu'ssions 'of 26 fgature films and the,n by entries dealing with Shakespearean perforrances on televiqion: The third 'pax't of the book constituAsa glade to avAilable media resources for tlip classroom. Ittries are arranged in three categories: Shakespeare's life'and' iimes, Shakespeare's theater, and Shakespeare 's plam. Each category, lists film strips, films, audi o-ca ssette tapes, and transparencies. The.geteral format of these entries gives the title, .number of parts, .grade level, number of frames .nr running time; whether color or bie ack and white, producer, year' of .prOduction, distributor, ut,itles of parts',4brief description of cOntent, and reviews.A direCtory of producers, distributors, ard rental sources is .alst provided in the 10 book.(FL)- 4 to P . -

Direct 75 75 Checklist! Spotlight On

75 LE PROPOSTE DI J-POP & EDIZIONI BD Tomohito ODA PAG 15 komi can't communicate COMI-SA WA, COMYUSHO DESU. by Tomohito ODA ©2016 Tomohito ODA/ SHOGAKUKAN. COPIA GRATUITA - VIETATA LA VENDITA DIRECT 75 75 CHECKLIST! SPOTLIGHT ON DIRECT è una pubblicazione di Edizioni BD S.r.l. Viale Coni Zugna, 7 - 20144 - Milano tel +39 02 84800751 - fax +39 02 89545727 www.edizionibd.it www.j-pop.it JIBAKU SHOUNEN HANAKO-KUN Coordinamento Georgia Cocchi Pontalti ©2015 Aida Iro/SQUARE ENIX CO., LTD. Art Director Giovanni Marinovich Hanno collaborato Davide Bertaina, Jacopo Costa Buranelli, Giorgio Cantù, Ilenia Cerillo, Francesco TITOLO ISBN PREZZO USCITA INDICATIVA Paolo Cusano, Daniel de Filippis, Matteo de Marzo, ALFABETO SIMENON 9788834915387 € 20,00 NOVEMBRE Andrea Ferrari, Valentina Ghidini, Fabio Graziano, Eleonora Moscarini, Lucia Palombi, Valentina BARBARA 3 9788834915110 € 15,00 NOVEMBRE Andrea Sala, Federico Salvan, Marco Schiavone, BLUE PERIOD 2 9788834915073 € 6,50 NOVEMBRE Fabrizio Sesana CRITICAL ROLE: VOX MACHINA ORIGINS 1 9788834902387 € 19,00 OTTOBRE DEMON TUNE 4 9788834901724 € 5,90 NOVEMBRE UFFICIO COMMERCIALE FATTI FORZA, NAKAMURA! 9788834915080 € 6,90 NOVEMBRE tel. +39 02 36530450 GOBLIN SLAYER 09 9788834915097 € 6,50 NOVEMBRE [email protected] HANAKO KUN - I SETTE MISTERI DELL’ACCADEMIA KAMOME 2 9788834915127 € 5,90 NOVEMBRE [email protected] HELL’S PARADISE – JIGOKURAKU 7 9788834915103 € 5,90 NOVEMBRE [email protected] HELLSING NEW EDITION 4 9788832758993 € 15,00 NOVEMBRE DISTRIBUZIONE IN FUMETTERIE IL BISTURI E LA SPADA 4 9788834915110 € 15,00 NOVEMBRE Manicomix Distribuzione IL MITO DI CTHULHU - DELUXE EDITION 9788834903636 € 20,00 OTTOBRE Via IV Novembre, 14 - 25010 - San Zeno Naviglio (BS) IL MITO DI CTHULHU - REGULAR EDITION 9788834903629 € 7,50 NOVEMBRE www.manicomixdistribuzione.it KEMONO JIHEN 1 9788834915424 € 6,00 NOVEMBRE DISTRIBUZIONE IN LIBRERIE KILLING STALKING STAG.