Westernroman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

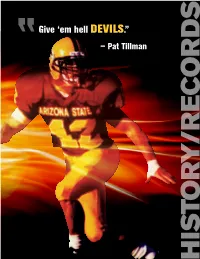

Give 'Em Hell Devils.”

Give ‘em hell DEVILS.” ” — Pat Tillman HISTORY/RECORDS Year-BY-Year StatiSticS RUSHING PASSING TOTAL OFFENSE PUNTS SCORING FIRST DOWNS Year Att.-Yds.-TD Avg./G A-C-I-TD Yds. Avg./G Pl.-Yds. Avg./G No. Avg. TD C-1 C-2 FG Pts. Avg./G R P Pn Tot. 1946 ASU (11) 451-870-NA 79.1 241-81-30-NA 1,073 97.6 692-1,943 176.6 81 34.6 14 7-14 0-0 0 93 8.5 49 41 11 101 Opponents 507-2,244-NA 204.0 142-61-9-NA 1,101 100.1 649-3,345 304.1 60 28.0 47 31-47 0-0 0 313 28.5 87 36 5 128 1947 ASU (11) 478-2,343-NA 213.0 196-77-15-NA 913 83.0 674-3,256 296.0 62 34.8 26 11-26 0-0 0 168 15.3 101 36 8 145 Opponents 476-2,251-NA 204.6 163-51-19-NA 751 68.3 639-3,002 272.9 69 34.2 35 24-35 0-0 0 234 21.3 96 20 5 121 1948 ASU (10) 499-2,188-NA 218.8 183-85-9-NA 1,104 110.4 682-3,292 329.2 40 32.5 41 20-41 0-0 3 276 27.6 109 46 8 163 Opponents 456-2,109-NA 210.9 171-68-19-NA 986 98.6 627-3,095 309.5 53 33.6 27 22-27 0-0 2 192 19.2 81 38 6 125 1949 ASU (9) 522-2,968-NA 329.8 144-56-17-NA 1,111 123.4 666-4,079 453.2 33 37.1 47 39-47 0-0 0 321 35.7 – – – 173 Opponents 440-1,725-NA 191.7 140-50-20-NA 706 78.4 580-2,431 270.1 61 34.7 26 15-26 0-0 0 171 19.0 – – – 111 1950 ASU (11) 669-3,710-NA 337.3 194-86-21-NA 1,405 127.7 863-5,115 465.0 51 36.1 58 53-58 0-0 1 404 36.7 178 53 11 242 Opponents 455-2,253-NA 304.5 225-91-27-NA 1,353 123.0 680-3,606 327.8 74 34.6 23 16-23 0-0 0 154 14.0 78 51 8 137 1951 ASU (11) 559-3,350-NA 145.8 130-51-11-NA 814 74.0 689-4,164 378.5 48 34.3 45 32-45 0-0 2 308 28.0 164 27 8 199 Opponents 494-1,604-NA 160.4 206-92-10-NA 1,426 129.6 700-3,030 -

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Papers Correspondence Rev

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis papers Correspondence Rev. July 2017 AC The Art of Cars BH Beyond the Hills BTK Billy the Kid DC David Crockett EDL En Divina Luz HW Heaven’s Window LH Lincoln Highway MK Mankiller OC Oklahoma Crossroads OM Oil Man PBF Pretty Boy Floyd R66 Route 66 RWW The Real Wild West W365 The Wild West 365 WDY Way Down Yonder 1:1 21st Century Fox 66 Diner (R66) 1:2 66 Federal Credit Union Gold Club 1:3 101 Old Timers Association, The. Includes certificate of incorporation, amended by-laws, projects completed, brief history, publicity and marketing ideas. 1:4 101 Old Timers Association, The. Board and association meeting minutes, letters to members: 1995-1997. 1:5 101 Old Timers Association, The. Board and association meeting minutes, letters to members: 1998-2000. 1:6 101 Old Timers Association, The. Personal correspondence: 1995-2000. 1:7 101 Old Timers Association, The. Newsletters (incomplete run): 1995-2001. 1:8 101 Old Timers Association, The. Ephemera. 1:9 AAA AARP 1:10 ABC Entertainment 1:11 AASHTO (American Association of State Highway and Traffic Officers) 1:12 A Loves L. Productions, Inc. A-Town Merchants Wholesale Souvenirs Abell, Shawn 1:13 Abney, John (BH) Active Years 1:14 Adams, Barb Adams, Steve Adams, W. June Adams, William C. 1:15 Adler, Abigail (PBF) Adventure Tours (R66) 1:16 Adweek 1:17 Aegis Group Publishers, The A.K. Smiley Public Library Akron Police Department, The Alan Rhody Productions Alansky, Marilyn (OM) 1:18 Alaska Northwest Books 2:1 [Alberta] Albuquerque Convention and Visitors Bureau Albuquerque Journal Albuquerque Museum, The. -

Unclaimed Property for County: JOHNSTON 7/16/2019

Unclaimed Property for County: JOHNSTON 7/16/2019 OWNER NAME ADDRESS CITY ZIP PROP ID ORIGINAL HOLDER ADDRESS CITY ST ZIP 1614 BONITO LANE CONDO ASSOCIATION C/O JOHNS EASTERN COMPANY INC 901 CLAYTON 27520 14866414 MARKEL CORPORATION 4521 HIGHWOODS PKWY GLEN ALLEN VA 23060 TOWN CENTRE BLVD PMB 146 A E CLARITY CONSULTING AND TRAINING LLC 209 LONG NEEDLE DR CLAYTON 27520-8539 15230083 NC DEPT OF REVENUE PSRM BUSINESS TAX REFUNDS P O BOX RALEIGH NC 27640 25000 ABARCA GEORGE 304 CHERRY LAUREL DR CLAYTON 27527 15830976 LOWES COMPANIES INC & SUBSIDIARIES 1000 LOWES BLVD MOORESVILLE NC 28117 ABARCA HERNANDEZ FAUSTINA 2213 STEPHANIE LN CLAYTON 27520-8407 14988700 NC DEPT OF REVENUE P O BOX 25000 IMPREST CASH FUND RALEIGH NC 27640 ABBOTT CHRISTIE A PO BOX 194 PINE LEVEL 27568-0194 14938243 ALLSTATE INDEMNITY COMPANY PO BOX 37946 ATTN: UNCLAIMED PROPERTY CHARLOTTE NC 28237-7946 ABBOTT TRAVIS 1479 PRESTON RD SMITHFIELD 27577-7750 15883848 DUKE ENERGY PROGRESS, LLC 550 S TRYON ST DEC44A CHARLOTTE NC 28202 ABDIRAHMAN AHMANI M 120 PREAKNESS DR 27527 14819566 BATTLEGROUND RESTAURANT GROUP INC PO BOX 10398 GREENSBORO NC 27404 ABDOLLAHIAN PEIMON 2167 VALLEY DR CLAYTON 27520-6584 15476832 ERIE INSURANCE EXCHANGE 100 ERIE INSURANCE PL ERIE PA 16530 ABDURAKHMANOV ZAMIR 642 AVERASBORO DR CLAYTON 27520 14879314 PAYPAL INC 12312 PORT GRACE BLVD ATTN: LA VISTA NE 68128 UNCLAIMED PROPERTY ABIGAIL N STEPHENSON 35 WHITE BARK LN CLAYTON 27520 15357495 BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF TEACHERS AND STATEEMPLOYEES COM MAJ MED PO BOX 2291 DURHAM NC 27702 4615 UNIVERSITY DR ABRAMS -

Morgan Kane: a Nordic Western

Morgan Kane: A Nordic Western Karoline Aksnes Morgan Kane: A Nordic Western Avhandling for graden philosophiae doctor (ph.d.) Universitetet i Agder Fakultet for humaniora og pedagogikk 2018 Doktoravhandlingar ved Universitetet i Agder 198 ISSN: 1504-9272 ISBN: 978-82-7117-897-0 Karoline Aksnes, 2018 Trykk: 07 Media Oslo Acknowledgements This dissertation is the result of 3 years spent with Morgan Kane. During that time, I have learned much about Kane but perhaps even more about myself. And I have learned that writing a dissertation really is a process. In this process I have many people to thank. First, I would like to thank my supervisor Michael J. Prince for excellent supervision throughout this project. Thank you, Mike, for giving me tough deadlines AND ice cream breaks. I would also like to thank my co-supervisor Asbjørn Grønstad for all your help and feedback. I appreciate how you ask questions which makes me think about my material in new ways. And my English mentor Øyunn Hestetun – thank you for helping me develop an idea into a project-proposal, and for your continuous interest and encouragement throughout. Thank you, Marit Aamodt Nielsen, for all your help with proofreading, and for being my go-to person for good advice. Colleagues and friends at the University of Agder, thank you for making the university a good place to be. A particular nod to my people in “morra-kaffen,” on Knausen, on the quiz-team and in Major Laudals Vei. You are the best! I am also grateful to Institutt for fremmedspråk og oversettelse at the University of Agder for making this project possible. -

University Graduate Catalog 2015-2016

University Graduate Catalog 2015-2016 2015-2016 OKWU University Graduate Catalog Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 3 UNIVERSITY CATALOG RIGHT TO CHANGE POLICY ......................................................... 5 ACADEMIC CALENDAR ................................................................................................ 6 OKWU DISTINCTIVES ................................................................................................. 7 Mission ........................................................................................................... 7 Statement of Purpose ....................................................................................... 7 Doctrinal Statement ......................................................................................... 8 Institutional Objectives ..................................................................................... 9 Global Graduate Learning Outcomes ................................................................. 10 Diversity and Unity ......................................................................................... 11 Statement on Human Sexuality........................................................................ 12 GENERAL GRIEVANCE POLICY .................................................................................... 14 STUDENT LIFE ........................................................................................................ -

The American West and the World

THE AMERICAN WEST AND THE WORLD The American West and the World provides a synthetic introduction to the trans- national history of the American West. Drawing from the insights of recent scholarship, Janne Lahti recenters the history of the U.S. West in the global contexts of empires and settler colonialism, discussing exploration, expansion, migration, violence, intimacies, and ideas. Lahti examines established subfields of Western scholarship, such as borderlands studies and transnational histories of empire, as well as relatively unexplored connections between the West and geographically nonadjacent spaces. Lucid and incisive, The American West and the World firmly situates the historical West in its proper global context. Janne Lahti is Adjunct Professor of History at the University of Helsinki and the editor of American Studies in Scandinavia. THE AMERICAN WEST AND THE WORLD Transnational and Comparative Perspectives Janne Lahti NEW YORK AND LONDON First published 2019 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2019 Taylor & Francis The right of Janne Lahti to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Dudleyla2013.Pdf (4.817Mb)

THE LEGACY OF ARTHUR AND SHIFRA SILBERMAN: AN UNPARALLELED COLLECTION OF AMERICAN INDIAN PAINTING AND SCHOLARSHIP by LEIGH A. DUDLEY A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY-MUSEUM STUDIES University of Central Oklahoma May 2013 ii ABSTRACT Arthur Silberman (1924-95) and his wife, Shifra Silberman (1932-90), spent the majority of their lives collecting, preserving, and promoting the unique beauty of American Indian art. From the early establishment of American Indian works on paper to the more modern and disciplined adaptation of Indian artistic traditions, this collection, now in the possession of the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum (NCWHM), encompasses an important evolution not only in Native American painting, but in American painting in general. The Silbermans labored to inspire an appreciation for Indian art in others by increasing public awareness through lectures, publications, and exhibits. Their dedication to collecting and studying American Indian art and culture in addition to their gathering of research materials, including oral history interviews with Traditional artists and those that knew them, enabled a flood of knowledge on the subject and influenced the world of art including the scope of the collections at the NCWHM. Listening to the voices of Native Americans in the interviews conducted by the Silbermans, one begins to understand not only the ancestral traditions which served as the foundation for Native art, but also the artists’ need to conform and mold their creative visions to early twentieth-century political and monopolistic demands in order to sustain the American Indian economy and maintain their cultural customs. -

The American West and the World

THE AMERICAN WEST AND THE WORLD The American West and the World provides a synthetic introduction to the trans- national history of the American West. Drawing from the insights of recent scholarship, Janne Lahti recenters the history of the U.S. West in the global contexts of empires and settler colonialism, discussing exploration, expansion, migration, violence, intimacies, and ideas. Lahti examines established subfields of Western scholarship, such as borderlands studies and transnational histories of empire, as well as relatively unexplored connections between the West and geographically nonadjacent spaces. Lucid and incisive, The American West and the World firmly situates the historical West in its proper global context. Janne Lahti is Adjunct Professor of History at the University of Helsinki and the editor of American Studies in Scandinavia. THE AMERICAN WEST AND THE WORLD Transnational and Comparative Perspectives Janne Lahti NEW YORK AND LONDON First published 2019 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2019 Taylor & Francis The right of Janne Lahti to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

United States 2015 Stockholm Junior Water Prize State Winners

United States 2015 Stockholm Junior Water Prize State Winners Alabama Megan Lange Removal of BTEX from Storm Water using Improved HDTMA Nano-Particle Enhanced Reactive Porous Concrete Auburn High School Teacher – Jacque Middleton Sponsored by the Alabama Water Environment Association Alaska Alta Dean Conclusions from an IV Year Research Study: Ocean Acidification in Prince William Sound, Alaska Colony High School Science Teacher – Dorrie Dean Sponsored by the Alaska Water Wastewater Management Association Arizona Amanda Minke An Engineered System for Filtering Pb2+ using Chlorophyta - Phase 2 Immaculate Heart High School Science Teacher – Danielle Abrames Sponsored by the AZ Water Arkansas Sophia Ly The pH Dependence of the Biosorption of Nickel (II) Ions by Escherichia coli Arkansas School for Mathematics, Sciences and the Arts Science Teacher – Dr. Fred Buzen Sponsored by the Arkansas Water Environment Association California Michele Eggleston Is It Clear? Is it Clean? Correlating Turbidity and Bacterial Contamination Using a Home Made Nephelometer Mt Everest Academy Science Teacher – Trudy Pachon Sponsored by the California Water Environment Association Colorado Hannah Fischer Pharmacoenvironmentology: Developing a Baseline for PPCP Contaminant Levels at the Monte Vista Wildlife Refuge Sierra Grande School Science Teacher – Judy Lopez Sponsored by the Rocky Mountain Water Environment Association Connecticut Julia Ennis The Analysis of Clay Flocculation’s Effect on the Benthic Zone Used as a Mitigation Technique for Harmful Algal Blooms -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS 13881 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS AGNES KJORLIE GEELAN, Days Around the Writer's Discipline That, She State of North Dakota

June 16, 1986 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 13881 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS AGNES KJORLIE GEELAN, days around the writer's discipline that, she state of North Dakota. <By contrast, 5,000 NORTH DAKOTA'S FIRST LADY says, delights her. copies of a nonfiction book by a new author "Writing is fun! It's the most enjoyable is considered a respectable showing-mar activity I can imagine," she says, pouring a keted from coast to coast.) HON. BYRON L. DORGAN cup of coffee and setting down in the bed "Bill was a fascinating, misunderstood OF NORTH DAKOTA room she's converted into a study and re man, born 25 years before this time," Agnes IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES search library. sums up the career of the man who so often "My dear friend, Sister Anne Burns of stood alone during his last isolationist days Monday, June 16, 1986 Mary College, told me years ago that to in the U.S. Senate. "I was amazed to find Mr. DORGAN of North Dakota. Mr. Speaker, become a writer I must write every day. She how many errors had appeared in published gave me a tiny owl to remind me, and it's accounts of his career and adventures over Agnes Kjorlie Geelan recently celebrated her watched from the wall ever since," she re the years." 90th birthday, still bright, sharp, and quick to flects. "I had never thought I could write. Colleagues urged Agnes to follow up the discuss the day's events. Since I discovered that I could, I've been success of her Langer book (which she has Her public career is an inspiration to all who faithful to her advice." allowed to go out of print, despite excellent hear about it, especially the young women of Encouraged by Sister Anne and Alice prospects for continued sales) with more today. -

Cowboy Chronicle October 2015 Page 1

Cowboy Chronicle October 2015 Page 1 VISIT US AT SASSNET .COM Cowboy Chronicle Page 2 October 2015 The Cowboy Chronicle CONTENTS 5 SASS CONVENTION ((( SIGN-U P TODA Y!! ! ))) Editorial Staff 6 FROM THE EDITOR Skinny The SASS ® Organization, What Does SASS Do? Editor-in-Chief 8 NEW S Misty Moonshine Cowboy Action Shooting TM Display Garners Much Interest 9 LETTERS & OPINIONS Managing Editor Tex and Cat Ballou 10 COVER FEATURE Editors Emeritus The Norseman Trail CAS Nordic Championship 2015 14-35 ON THE RANGE Adobe Illustrator Eas’dern Shore Round-Up 2015 Layout & Design 36, 38 CLUB REPORTS Mac Daddy Pine Mountain Posse • The Guns Of August 39 THE WILD BUNCH CORNER Graphic Design Muster At Fort Misery 2015 Square Deal Jim 40-46 GUNS & GEAR Advertising Manager Dispatches From Camp Baylor (703) 764-5949 • Cell: (703) 728-0404 48-51 HISTORY [email protected] Private Watkins’ War • Little Known Famous People 52 REVIEWS BOOKS Staff Writers Pistol Man Big Dave, Capgun Kid 54-59 PROFILES Capt. George Baylor Shadow Carson • How I Got My Alias • Scholarship Recipients Col. Richard Dodge 60-63 ARTICLES Jesse Wolf Hardin, Joe Fasthorse One Pot Chuck • CAS Initial & Basic Training Outline Larsen E. Pettifogger, Palaver Pete 64-73 THE VIEW FROM OUR LENS Tennessee Tall and Rio Drifter Texas Flower 74, 75 GENERAL STORE /CLASSIFIEDS Whooper Crane and the Missus The Cowboy Chronicle 76, 77 SASS MERCANTILE is published by Nice Collectibles The Wild Bunch, Board of Directors of The Single Action Shooting Society. 78, 79 SASS NEW MEMBERS For advertising information and rates, administrative, and edi to rial offices contact: 80 SASS AFFILIATED CLUBS (MONTHLY) (ANNUA L) Chronicle Administrator 215 Cowboy Way • Edgewood, NM 87015 (505) 843-1320 • FAX (505) 843-1333 Visit our Website at email: [email protected] Hall of Fame http://www.sassnet.com SASSNET.COM The Cowboy Chronicle inductee (ISSN 15399877) is published Grey Fox SASS ® Trademarks monthly by the Single Action Shooting Society, 215 SASS ®, Single Action Shooting Society ®, Cowboy Way, Edgewood, NM 87015. -

Dog Name Count Buddy 456 Bella 427 Lucy 380 Max 332 Molly 323

Dog Name Count Buddy 456 Bella 427 Lucy 380 Max 332 Molly 323 Daisy 305 Charlie 283 Sadie 279 Sophie 249 Bailey 234 Maggie 230 Jack 209 Abby 204 Bear 186 Duke 185 Chloe 177 Cooper 170 Jake 168 Toby 167 Zoey 164 Harley 161 Tucker 159 Ginger 146 Pepper 144 Riley 142 Shadow 141 Lily 139 Rocky 139 Lola 136 Gracie 130 Bandit 129 Missy 124 Roxy 122 Coco 116 Teddy 116 Angel 114 Annie 114 Lilly 114 Rosie 112 Rusty 111 Buster 110 Lady 110 Ruby 107 Penny 103 Murphy 102 Scout 100 Lucky 96 Sammy 96 Oscar 92 Sam 92 Dexter 90 Zoe 90 Bentley 85 Zeus 85 Gus 83 Jasper 83 Koda 83 Sasha 82 Marley 80 Dakota 79 Luna 79 Emma 78 Oliver 76 Piper 76 Ellie 75 Stella 74 Belle 73 Cody 72 Henry 72 Moose 72 Peanut 71 Princess 71 Tank 71 Baxter 70 Mia 70 Winston 68 Jasmine 67 Jax 67 Kona 67 Beau 66 Bo 66 Shelby 66 Blue 65 Jackson 65 Scooter 65 Hunter 63 Izzy 63 Joey 63 Gunner 61 Honey 61 Mocha 61 Ruger 59 Leo 58 Loki 58 Diesel 56 Gizmo 56 Boomer 54 Lexi 53 Maddie 53 Chewy 52 Copper 52 Hank 52 Heidi 52 Otis 52 Holly 50 Milo 50 Sassy 50 Baby 49 Dixie 49 Thor 49 Cocoa 48 Minnie 48 Patches 48 Rudy 48 Sugar 48 Maya 47 Millie 47 Nala 47 Rex 47 Bubba 46 Chico 46 Louie 46 LuLu 46 Willow 46 Oreo 45 Sparky 45 Chance 44 Katie 44 Misty 44 Roxie 44 Scooby 43 Brutus 42 Dozer 42 Frankie 42 Smokey 42 Wilson 42 Trixie 41 Brody 40 Nikki 40 Cookie 39 Mandy 39 Jessie 38 Spike 38 Benny 37 Peaches 37 Roscoe 37 Samson 37 Snickers 37 Bruno 36 Chester 36 Hazel 36 Rowdy 36 Callie 35 Mac 35 Sandy 35 George 34 Josie 34 Lacey 34 Ranger 34 Ace 33 Layla 33 Macy 33 Rascal 33 Reggie 33 Rosco 33 Rufus