Dudleyla2013.Pdf (4.817Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS 7536 Pochoir Prints of Ledger Drawings by the Kiowa Five

MS 7536 Pochoir prints of ledger drawings by the Kiowa Five National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland, Maryland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Local Numbers................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical................................................................................................... -

{Download PDF} Creek Country the Creek Indians and Their World 1St

CREEK COUNTRY THE CREEK INDIANS AND THEIR WORLD 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robbie Ethridge | 9780807854952 | | | | | Creek Country The Creek Indians and Their World 1st edition PDF Book During the winter, additional warmth was provided by bear skins and buffalo hides. Creek Country provides an in-depth description of many aspects of Creek life in the nineteenth century and a window on the changes they experienced. Seller Inventory S Russell Allen. The women then cooked sofkey and fried the fish for a feast. Contact: Nathan Martin. Contact: Gale Thrower. Trade patterns, gender roles, and political structure all changed with the redeployment of American citizens. Employment and Economic Traditions The early Creeks enjoyed a comfortable living based on agriculture and hunting. Trade expanded, and they began to sell not only venison, hides, and furs, but also honey, beeswax, hickory nut oil, and other produce. Richard Highnote rated it really liked it Feb 16, The Removal Treaty of guaranteed the Creeks political autonomy and perpetual ownership of new homelands in Indian Territory in return for their cession of remaining tribal lands in the East. During courtship, the man might woo the woman by playing plaintive melodies on a flute made either of hardwood or a reed. In , the U. Ethridge finds that the world of Creek Indians was quite diverse in terms of the composition of the population, the economic activity in which Creek Indians participated, and the varying landscapes in which they lived. Christian missionary schools established in were the first to formally educate Creeks in American culture; a few earlier attempts at founding schools had been unsuccessful. -

Friends of the Capitol 2009-June 2010 Report

Friends of the Capitol 2009-June 2010 Report Our Mission Statement: Friends of the Capitol is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) corporation that is devoted to maintaining and improving the beauty and grandeur of the Oklahoma State Capitol building and showcasing the magnificent gifts of art housed inside. This mission is accomplished through a partnership with private citizens wishing to leave their footprint in our state's rich history. Education and Development In 2009 and 2010 Friends of the Capitol (FOC) participated in several educational and developmental projects informing fellow Oklahomans of the beauty of the capitol and how they can participate in the continuing renovations of Oklahoma State Capitol building. In March of 2010, FOC representatives made a trip to Elk City and met with several organizations within the community and illustrated all the new renovations funded by Friends of the Capitol supporters. Additionally in 2009 FOC participated in the State Superintendent’s encyclo-media conference and in February 2010 FOC participated in the Oklahoma City Public Schools’ Professional Development Day. We had the opportunity to meet with teachers from several different communities in Oklahoma, and we were pleased to inform them about all the new restorations and how their school’s name can be engraved on a 15”x30”paver, and placed below the Capitol’s south steps in the Centennial Memorial Plaza to be admired by many generations of Oklahomans. Gratefully Acknowledging the Friends of the Capitol Board of Directors Board Members Ex-Officio Paul B. Meyer, Col. John Richard Chairman USA (Ret.) MA+ Architecture Oklahoma Department Oklahoma City of Central Services Pat Foster, Vice Chairman Suzanne Tate Jim Thorpe Association Inc. -

A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong

Tulsa Law Review Volume 48 Issue 2 Winter 2012 A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong Wyatt M. Cox Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Wyatt M. Cox, A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong, 48 Tulsa L. Rev. 373 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol48/iss2/20 This Casenote/Comment is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cox: A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong A RESERVED RIGHT DOES NOT MAKE A WRONG 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 374 II. TREATIES WITH THE TRIBAL NATIONS ............................................. 375 A. The Canons of Construction. ........................... ...... 375 B. The Power and Purpose of the Indian Treaty ............................... 376 C. The Equal Footing Doctrine .............................................377 D. A Brief Overview of the Policy History of Treaties ............ ........... 378 E. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.........................380 III. THE ESTABLISHMENT AND EXPANSION OF THE INDIAN RESERVED WATER RIGHT ....381 A. Winters v. United States: The Establishment of Reserved Indian Water Rights...................................................382 B. Arizona v. California:Not Only Enough Water to Fulfill the Purposes of Today, but Enough to Fulfill the Purposes of Forever ...................... 383 C. Cappaertv. United States: The Supreme Court Further Expands the Winters Doctrine ........................................ 384 IV. Two OKLAHOMA CASES THAT SUPPORT THE TRIBAL NATION CLAIMS .................... 385 A. Choctaw Nation v. Oklahoma (The Arkansas River Bank Case) .................. -

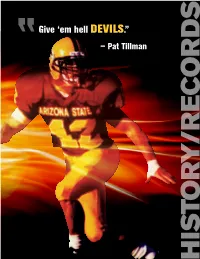

Give 'Em Hell Devils.”

Give ‘em hell DEVILS.” ” — Pat Tillman HISTORY/RECORDS Year-BY-Year StatiSticS RUSHING PASSING TOTAL OFFENSE PUNTS SCORING FIRST DOWNS Year Att.-Yds.-TD Avg./G A-C-I-TD Yds. Avg./G Pl.-Yds. Avg./G No. Avg. TD C-1 C-2 FG Pts. Avg./G R P Pn Tot. 1946 ASU (11) 451-870-NA 79.1 241-81-30-NA 1,073 97.6 692-1,943 176.6 81 34.6 14 7-14 0-0 0 93 8.5 49 41 11 101 Opponents 507-2,244-NA 204.0 142-61-9-NA 1,101 100.1 649-3,345 304.1 60 28.0 47 31-47 0-0 0 313 28.5 87 36 5 128 1947 ASU (11) 478-2,343-NA 213.0 196-77-15-NA 913 83.0 674-3,256 296.0 62 34.8 26 11-26 0-0 0 168 15.3 101 36 8 145 Opponents 476-2,251-NA 204.6 163-51-19-NA 751 68.3 639-3,002 272.9 69 34.2 35 24-35 0-0 0 234 21.3 96 20 5 121 1948 ASU (10) 499-2,188-NA 218.8 183-85-9-NA 1,104 110.4 682-3,292 329.2 40 32.5 41 20-41 0-0 3 276 27.6 109 46 8 163 Opponents 456-2,109-NA 210.9 171-68-19-NA 986 98.6 627-3,095 309.5 53 33.6 27 22-27 0-0 2 192 19.2 81 38 6 125 1949 ASU (9) 522-2,968-NA 329.8 144-56-17-NA 1,111 123.4 666-4,079 453.2 33 37.1 47 39-47 0-0 0 321 35.7 – – – 173 Opponents 440-1,725-NA 191.7 140-50-20-NA 706 78.4 580-2,431 270.1 61 34.7 26 15-26 0-0 0 171 19.0 – – – 111 1950 ASU (11) 669-3,710-NA 337.3 194-86-21-NA 1,405 127.7 863-5,115 465.0 51 36.1 58 53-58 0-0 1 404 36.7 178 53 11 242 Opponents 455-2,253-NA 304.5 225-91-27-NA 1,353 123.0 680-3,606 327.8 74 34.6 23 16-23 0-0 0 154 14.0 78 51 8 137 1951 ASU (11) 559-3,350-NA 145.8 130-51-11-NA 814 74.0 689-4,164 378.5 48 34.3 45 32-45 0-0 2 308 28.0 164 27 8 199 Opponents 494-1,604-NA 160.4 206-92-10-NA 1,426 129.6 700-3,030 -

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Papers Correspondence Rev

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis papers Correspondence Rev. July 2017 AC The Art of Cars BH Beyond the Hills BTK Billy the Kid DC David Crockett EDL En Divina Luz HW Heaven’s Window LH Lincoln Highway MK Mankiller OC Oklahoma Crossroads OM Oil Man PBF Pretty Boy Floyd R66 Route 66 RWW The Real Wild West W365 The Wild West 365 WDY Way Down Yonder 1:1 21st Century Fox 66 Diner (R66) 1:2 66 Federal Credit Union Gold Club 1:3 101 Old Timers Association, The. Includes certificate of incorporation, amended by-laws, projects completed, brief history, publicity and marketing ideas. 1:4 101 Old Timers Association, The. Board and association meeting minutes, letters to members: 1995-1997. 1:5 101 Old Timers Association, The. Board and association meeting minutes, letters to members: 1998-2000. 1:6 101 Old Timers Association, The. Personal correspondence: 1995-2000. 1:7 101 Old Timers Association, The. Newsletters (incomplete run): 1995-2001. 1:8 101 Old Timers Association, The. Ephemera. 1:9 AAA AARP 1:10 ABC Entertainment 1:11 AASHTO (American Association of State Highway and Traffic Officers) 1:12 A Loves L. Productions, Inc. A-Town Merchants Wholesale Souvenirs Abell, Shawn 1:13 Abney, John (BH) Active Years 1:14 Adams, Barb Adams, Steve Adams, W. June Adams, William C. 1:15 Adler, Abigail (PBF) Adventure Tours (R66) 1:16 Adweek 1:17 Aegis Group Publishers, The A.K. Smiley Public Library Akron Police Department, The Alan Rhody Productions Alansky, Marilyn (OM) 1:18 Alaska Northwest Books 2:1 [Alberta] Albuquerque Convention and Visitors Bureau Albuquerque Journal Albuquerque Museum, The. -

The Native American Fine Art Movement: a Resource Guide by Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba

2301 North Central Avenue, Phoenix, Arizona 85004-1323 www.heard.org The Native American Fine Art Movement: A Resource Guide By Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba HEARD MUSEUM PHOENIX, ARIZONA ©1994 Development of this resource guide was funded by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. This resource guide focuses on painting and sculpture produced by Native Americans in the continental United States since 1900. The emphasis on artists from the Southwest and Oklahoma is an indication of the importance of those regions to the on-going development of Native American art in this century and the reality of academic study. TABLE OF CONTENTS ● Acknowledgements and Credits ● A Note to Educators ● Introduction ● Chapter One: Early Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Two: San Ildefonso Watercolor Movement ● Chapter Three: Painting in the Southwest: "The Studio" ● Chapter Four: Native American Art in Oklahoma: The Kiowa and Bacone Artists ● Chapter Five: Five Civilized Tribes ● Chapter Six: Recent Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Seven: New Indian Painting ● Chapter Eight: Recent Native American Art ● Conclusion ● Native American History Timeline ● Key Points ● Review and Study Questions ● Discussion Questions and Activities ● Glossary of Art History Terms ● Annotated Suggested Reading ● Illustrations ● Looking at the Artworks: Points to Highlight or Recall Acknowledgements and Credits Authors: Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba Special thanks to: Ann Marshall, Director of Research Lisa MacCollum, Exhibits and Graphics Coordinator Angelina Holmes, Curatorial Administrative Assistant Tatiana Slock, Intern Carrie Heinonen, Research Associate Funding for development provided by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Copyright Notice All artworks reproduced with permission. -

Painting Culture, Painting Nature Stephen Mopope, Oscar Jacobson, and the Development of Indian Art in Oklahoma by Gunlög Fur

UNIVERSITY OF FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OKLAHOMA PRESS 9780806162874.TIF BOOKNEWS Explores indigenous and immigrant experiences in the development of American Indian art Painting Culture, Painting Nature Stephen Mopope, Oscar Jacobson, and the Development of Indian Art in Oklahoma By Gunlög Fur In the late 1920s, a group of young Kiowa artists, pursuing their education at the University of Oklahoma, encountered Swedish-born art professor Oscar Brousse Jacobson (1882–1966). With Jacobson’s instruction and friendship, the Kiowa Six, as they are now known, ignited a spectacular movement in American Indian art. Jacobson, who was himself an accomplished painter, shared a lifelong bond with group member Stephen Mopope (1898–1974), a prolific Kiowa painter, dancer, and musician. Painting Culture, Painting Nature explores the joint creativity of these two visionary figures and reveals how indigenous and immigrant communities of the MAY 2019 early twentieth century traversed cultural, social, and racial divides. $34.95s CLOTH 978-0-8061-6287-4 368 PAGES, 6 X 9 Painting Culture, Painting Nature is a story of concurrences. For a specific period 15 COLOR AND 22 B&W ILLUS., 3 MAPS immigrants such as Jacobson and disenfranchised indigenous people such as ART/AMERICAN INDIAN Mopope transformed Oklahoma into the center of exciting new developments in Indian art, which quickly spread to other parts of the United States and to Europe. FOR AUTHOR INTERVIEWS AND OTHER Jacobson and Mopope came from radically different worlds, and were on unequal PUBLICITY INQUIRIES CONTACT: footing in terms of power and equality, but they both experienced, according to KATIE BAKER, PUBLICITY MANAGER author Gunlög Fur, forms of diaspora or displacement. -

CIRCLE of HONOR Muscogee (Creek) Elder to Be Recognized for Work Passing on Culture & Traditions 4 NATIVE OKLAHOMA | JANUARY 2016

NATIVE OKLAHOMA | JANUARY 2016 JANUARY 2016 Red Earth calls for artists AmeriCorps reaches out to Osage Nation Gingerbread Pumpkin Cheesecake recipe CIRCLE OF HONOR Muscogee (Creek) elder to be recognized for work passing on culture & traditions 4 NATIVE OKLAHOMA | JANUARY 2016 Sam Proctor Muscogee (Creek) elder to be inducted into Tulsa City-County Library’s Circle of Honor Tulsa City-County Library’s American Indian Proctor, Muscogee (Creek), was born south of Hanna in Resource Center will induct Sam Proctor into the Weogufkee community of Oklahoma, the heart of the the Circle of Honor during a special presentation Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and is a lifelong Oklahoman. He is a descendant of Opethleyahola, one of the great Creek March 5, 2016, at 10:30 a.m. at Hardesty leaders. Regional Library’s Connor’s Cove, 8316 E. 93rd Proctor has dedicated his life’s mission to encouraging St. families to incorporate Muscogee (Creek) traditions in their By JOHN FANCHER daily routines. He believes that the language and traditions are vital to maintaining a way of life that promotes balance Proctor’s award presentation begins the monthlong celebration and harmony with family, friends and strangers. honoring the achievements and accomplishments of Native Americans. Award-winning and internationally acclaimed His knowledge of traditional and sustainable agriculture artist Dana Tiger, Muscogee (Creek), painted a portrait of was beneficial in the efforts to establish the Mvskoke Food Sam Proctor and will have prints for sale after his ceremony. Sovereignty Initiative in Okmulgee, Okla. in 2007. The Programs will be held throughout TCCL locations during purpose of the program is to help the Muscogee (Creek) March. -

Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century, 1991

BILLIE JANE BAGULEY LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES HEARD MUSEUM 2301 N. Central Avenue ▪ Phoenix AZ 85004 ▪ 602-252-8840 www.heard.org Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century, 1991 RC 10 Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century 2 Call Number: RC 10 Extent: Approximately 3 linear feet; copy photography, exhibition and publication records. Processed by: Richard Pearce-Moses, 1994-1995; revised by LaRee Bates, 2002. Revised, descriptions added and summary of contents added by Craig Swick, November 2009. Revised, descriptions added by Dwight Lanmon, November 2018. Provenance: Collection was assembled by the curatorial department of the Heard Museum. Arrangement: Arrangement imposed by archivist and curators. Copyright and Permissions: Copyright to the works of art is held by the artist, their heirs, assignees, or legatees. Copyright to the copy photography and records created by Heard Museum staff is held by the Heard Museum. Requests to reproduce, publish, or exhibit a photograph of an art works requires permissions of the artist and the museum. In all cases, the patron agrees to hold the Heard Museum harmless and indemnify the museum for any and all claims arising from use of the reproductions. Restrictions: Patrons must obtain written permission to reproduce or publish photographs of the Heard Museum’s holdings. Images must be reproduced in their entirety; they may not be cropped, overprinted, printed on colored stock, or bleed off the page. The Heard Museum reserves the right to examine proofs and captions for accuracy and sensitivity prior to publication with the right to revise, if necessary. -

Oklahoma Women

Oklahomafootloose andWomen: fancy–free Newspapers for this educational program provided by: 1 Oklahoma Women: Footloose and Fancy-Free is an educational supplement produced by the Women’s Archives at Oklahoma State University, the Oklahoma Commission on the Status of Women and The Oklahoman. R. Darcy Jennifer Paustenbaugh Kate Blalack With assistance from: Table of Contents Regina Goodwin Kelly Morris Oklahoma Women: Footloose and Fancy-Free 2 Jordan Ross Women in Politics 4 T. J. Smith Women in Sports 6 And special thanks to: Women Leading the Fight for Civil and Women’s Rights 8 Trixy Barnes Women in the Arts 10 Jamie Fullerton Women Promoting Civic and Educational Causes 12 Amy Mitchell Women Take to the Skies 14 John Gullo Jean Warner National Women’s History Project Oklahoma Heritage Association Oklahoma Historical Society Artist Kate Blalack created the original Oklahoma Women: watercolor used for the cover. Oklahoma, Foot-Loose and Fancy Free is the title of Footloose and Fancy-Free Oklahoma historian Angie Debo’s 1949 book about the Sooner State. It was one of the Oklahoma women are exciting, their accomplishments inspirations for this 2008 fascinating. They do not easily fi t into molds crafted by Women’s History Month supplement. For more on others, elsewhere. Oklahoma women make their own Angie Debo, see page 8. way. Some stay at home quietly contributing to their families and communities. Some exceed every expectation Content for this and become fi rsts in politics and government, excel as supplement was athletes, entertainers and artists. Others go on to fl ourish developed from: in New York, California, Japan, Europe, wherever their The Oklahoma Women’s fancy takes them. -

This Land Is Herland

9780806169262.TIF Examines the experiences and achievements of women activists in Oklahoma This Land Is Herland Gendered Activism in Oklahoma from the 1870s to the 2010s Edited by Sarah Eppler Janda and Patricia Loughlin Contributions by Chelsea Ball, Lindsey Churchill, Heather Clemmer, Amanda Cobb-Greetham, Sarah Eppler Janda, Farina King, Sunu Kodumthara, Patricia Loughlin, Amy L. Scott, Rowan Faye Steineker, Melissa N. Stuckey, Rachel E. Watson, and Cheryl Elizabeth Brown Wattley. Since well before ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 secured their right to vote, women in Oklahoma have sought to change and uplift their communities through political activism. This Land Is Herlandbrings together the stories of thirteen women activists and explores their varied experiences from the territorial period to the VOLUME 1 IN THE WOMEN AND THE AMERICAN WEST present. Organized chronologically, the essays discuss Progressive reformer Kate Bar- nard, educator and civil rights leader Clara Luper, and Comanche leader and activist JULY 2021 LaDonna Harris, as well as lesser-known individuals such as Cherokee historian and $24.95 PAPER 978-0-8061-6926-2 educator Rachel Caroline Eaton, entrepreneur and NAACP organizer California M. 318 PAGES, 6 X 9 Taylor, and Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) champion Wanda Jo Peltier Stapleton. 21 B&W ILLUS. U.S. HISTORY/WOMEN’S STUDIES Edited by Sarah Eppler Janda and Patricia Loughlin, the collection connects Okla- homa women’s individual and collective endeavors to the larger themes of intersec- ORDER ONLINE AT OUPRESS.COM tionality, suffrage, politics, motherhood, and civil rights in the American West and the United States. The historians explore how race, ethnicity, social class, gender, and ORDER BY PHONE political power shaped—and were shaped by—these women’s efforts to improve their INSIDE THE U.S.