Microsoft Word Viewer 97

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Introduction The cover image of a wire-and-bead-art radio embodies some of this book’s key themes. I purchased this radio on tourist-thronged Seventh Street in the Melville neighborhood of Johannesburg. The artist, Jonah, was an im- migrant who fled the authoritarianism and economic collapse in his home country of Zimbabwe. The technology is stripped down and simple. It is also a piece of art and, as such, a representation of radio. The wire, beadwork, and swath of a Coca-Cola can announce radio’s energy, commercialization, and global circulation in an African frame. The radio works, mechanically and aesthetically. The wire radio is whimsical. It points at itself and outward. No part of the radio is from or about Angola. But this little radio contains a regional history of decolonization, national liberation movements, people crossing borders, and white settler colonies that turned the Cold War hot in southern Africa. Powerful Frequencies focuses on radio in Angola from the first quarter of the twentieth century to the beginning of the twenty-first century. Like a radio tower or a wire-and-bead radio made in South Africa by a Zimbabwean im- migrant and then carried across the Atlantic to sit on a shelf in Bloomington, Indiana, this history exceeds those borders of space and time. While state broadcasters have national ambitions—having to do with creating a com- mon language, politics, identity, and enemy—the analysis of radio in this book alerts us to the sub- and supranational interests and communities that are almost always at play in radio broadcasting and listening. -

Angola Background Paper

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM ANGOLA UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, APRIL 1999 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY INFORMATION UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. PREFACE Angola has been an important source country of refugees and asylum-seekers over a number of years. This paper seeks to define the scope, destination, and causes of their flight. The first and second part of the paper contains information regarding the conditions in the country of origin, which are often invoked by asylum-seekers when submitting their claim for refugee status. The Country Information Unit of UNHCR's Centre for Documentation and Research (CDR) conducts its work on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment, with all sources cited. In the third part, the paper provides a statistical overview of refugees and asylum-seekers from Angola in the main European asylum countries, describing current trends in the number and origin of asylum requests as well as the results of their status determination. The data are derived from government statistics made available to UNHCR and are compiled by its Statistical Unit. Table of Contents 1. -

Angola Cabinda

Armed Conflicts Report - Angola Cabinda Armed Conflicts Report Angola-Cabinda (1994 - first combat deaths) Update: January 2007 Summary Type of Conflict Parties to the Conflict Status of the Fighting Number of Deaths Political Developments Background Arms Sources Economic Factors Summary: 2006 The Angolan government signed the Memorandum of Understanding in July 2006, a peace agreement with one faction of the rebel group FLEC (Front for the Liberation of the Cabinda Enclave). Because of this, and few reported conflict related deaths over the past two years (less than 25 per year), this armed conflict is now deemed to have ended. 2005 Government troops and rebels clashed on several occasions and the Angolan army continued to be accused of human rights abuses in the region. Over 50,000 refugees returned to Cabinda this year. 2004 There were few reported violent incidences this year. Following early reports of human rights abuses by both sides of the conflict, a visit by a UN representative to the region noted significant progress. Later, a human rights group monitoring the situation in Cabinda accused government security forces of human rights abuses. 50,000 refugees repatriated during the year, short of the UNHCR’s goal of 90,000. 2003 Rebel bands remained active even as the government reached a “clean up” phase of the military campaign in the Cabinda enclave that began in 2002. Both sides were accused of human rights violations and at least 50 civilians died. Type of Conflict: State formation Parties to the Conflict: 1) Government, led by President Jose Eduardo dos Santos: Ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA); 2) Rebels: The two main rebel groups, the Front for the Liberation of the Cabinda Enclave (FLEC) and the Front for the Liberation of the Cabinda Enclave Cabinda Armed Forces (FLEC FAC), announced their merger on 8 September 2004. -

A Military History of the Angolan Armed Forces from the 1960S Onwards—As Told by Former Combatants

Evolutions10.qxd 2005/09/28 12:10 PM Page 7 CHAPTER ONE A military history of the Angolan Armed Forces from the 1960s onwards—as told by former combatants Ana Leão and Martin Rupiya1 INTRODUCTION The history of the Angolan Armed Forces (FAA) remains largely unwritten—yet, understanding the FAA’s development is undoubtedly important both for future Angolan generations as well as for other sub- Saharan African countries. The FAA must first and foremost be understood as a result of several processes of integration—processes that began in the very early days of the struggle against Portuguese colonialism and ended with the April 2002 Memorandum of Understanding. Today’s FAA is a result of the integration of the armed forces of the three liberation movements that fought against the Portuguese—the MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola), the FNLA (National Front for the Liberation of Angola) and UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola). This was a process that developed over more than 30 years. The various phases that characterise the formation and development of the FAA are closely related to Angola’s recent political history, particularly the advent of independence in 1975 and the civil war that ensued. This chapter introduces that history with a view to contributing to a clearer understanding of the development of the FAA and its current role in a peaceful Angola. As will be discussed, while the FAA was formerly established in 1992 following the provisions of the Bicesse Peace Accords, its origins go back to: 7 Evolutions10.qxd 2005/09/28 12:10 PM Page 8 8 Evolutions & Revolutions • the Popular Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) and the integration over more than three decades of elements of the Portuguese Colonial Army; • the FNLA’s Army for the National Liberation of Angola (ELNA); and • UNITA’s Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FALA). -

Cabinda Notes on a Soon-To-Be-Forgotten War

INSTITUTE FOR Cabinda Notes on a soon-to-be-forgotten war João Gomes Porto Institute for Security Studies SECURITY STUDIES ISS Paper 77 • August 2003 Price: R10.00 CABINDA’S YEAR OF WAR: 2002 the Angolan government allegedly used newly- incorporated UNITA soldiers to “all but vanquish the The government of Angola considers… that it is indis- splintered separatist factions of the FLEC.”6 pensable to extend the climate of peace achieved in the whole territory and hence to keep its firm com- When the Angolan government and UNITA signed the mitment of finding a peaceful solution to the issue of Memorandum of Understanding on 4 April 2002, the Cabinda, within the Constitutional legality in force, situation in Cabinda had been relatively quiet for taking into account the interests of the country and the several months. Soon after, however, reports of clashes local population.1 in the Buco-Zau military region between government forces and the separatists began pouring out of Cabinda is the Cabindan’s hell.2 Cabinda. The FAA gradually advanced to the heart of the rebel-held territory, and by the end of October War in Angola may only now be over, 15 2002 it had destroyed Kungo-Shonzo, months after the government and UNITA the FLEC-FAC’s (Front for the Liberation (National Union for the Total Indepen- of the Enclave of Cabinda-Armed Forces dence of Angola) formally ended the The FAA are of Cabinda) main base in the munici- civil war that has pitted them against one pality of Buco-Zau. Situated 110km from another for the last three decades. -

Angola's Foreign Policy

ͻͺ ANGOLA’S AFRICA POLICY PAULA CRISTINA ROQUE ʹͲͳ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Paula Cristina Roque is currently finalising her PhD on wartime guerrilla governance (using Angola and South Sudan as case studies) at Oxford University. She is also a founding member of the South Sudan Centre for Strategic and policy Studies in Juba. She was previously the senior analyst for Southern Africa (covering Angola and Mozambique) with the International Crisis Group, and has worked as a consultant for several organizations in South Sudan and Angola. From 2008-2010 she was the Horn of Africa senior researcher, also covering Angola, for the Institute for Security Studies in Pretoria. ABOUT THE EGMONT PAPERS The Egmont Papers are published by Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an independent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision-making process. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 Operating Principles: permanent interests and shifting levers . 4 Bilateral Miscalculations in Guinea-Bissau and Cote D’Ivoire . 8 Democratic Republic of Congo and Republic of Congo: National Security Interests. 11 Multilateral Engagements: AU, Regional Organisations and the ICGLR . 16 Conclusion . 21 1 INTRODUCTION Angola is experiencing an existential transition that will change the way power in the country is reconfigured and projected. -

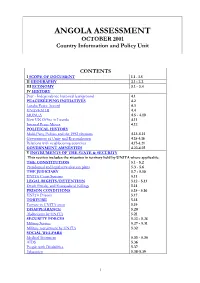

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.2 III ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.4 IV HISTORY Post - Independence historical background 4.1 PEACEKEEPING INITIATIVES 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.3 UNAVEM III 4.4 MONUA 4.5 - 4.10 New UN Office in Luanda 4.11 Internal Peace Moves 4.12 POLITICAL HISTORY Multi-Party Politics and the 1992 elections 4.13-4.14 Government of Unity and Reconciliation 4.15-4.16 Relations with neighbouring countries 4.17-4.21 GOVERNMENT AMNESTIES 4.22-4.25 V INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE & SECURITY This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. THE CONSTITUTION 5.1 - 5.2 Presidential and legislative election plans 5.3 - 5.6 THE JUDICIARY 5.7 - 5.10 UNITA Court Systems 5.11 LEGAL RIGHTS/DETENTION 5.12 - 5.13 Death Penalty and Extrajudicial Killings 5.14 PRISON CONDITIONS 5.15 - 5.16 UNITA Prisons 5.17 TORTURE 5.18 Torture in UNITA areas 5.19 DISAPPEARANCE 5.20 Abductions by UNITA 5.21 SECURITY FORCES 5.22 - 5.26 Military Service 5.27 - 5.31 Military recruitment by UNITA 5.32 SOCIAL WELFARE Medical Treatment 5.33 - 5.35 AIDS 5.36 People with Disabilities 5.37 Education 5.38-5.39 1 VI HUMAN RIGHTS- GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE SITUATION Introduction 6.1 SECURITY SITUATION Recent developments in the Civil War 6.2 - 6.17 Security situation in Luanda 6.18 - 6.19 Landmines 6.20 - 6.22 Human Rights monitoring 6.23 - 6.26 VII SPECIFIC GROUPS REFUGEES 7.1 Internally Displaced Persons & Humanitarian Situation 7.2-7.5 UNITA 7.6-7.8 Recent Political History of UNITA 7.9-7.12 UNITA-R 7.13-7.14 UNITA Military Wing 7.15-7.20 Surrendering UNITA Fighters 7.21 Sanctions against UNITA 7.22-7.25 F.L.E.C/CABINDANS 7.26 History of FLEC 7.27-7.28 Recent FLEC activity 7.29-7.34 The future of Cabindan separatists 7.35 ETHNIC GROUPS 7.36-7.37 Bakongo 7.38-7.46 WOMEN 7.47 Discrimination against women 7.48-7.59 CHILDREN 7.50-7.55 VIII RESPECT FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. -

Child Soldiers in Angola

ANGOLA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org Vol. 15, No. 10 (A) – April 2003 I was taken away in 1999 when I was thirteen years old. At first, I was used to transport arms, supplies, and other materials. There were other children in our group, about thirty. We were soon given training on how to fight. We shot with AK-47s and other weapons. I was the youngest in my troop of about seventy, children and adults. We were on the front lines and I was sick, with bouts of malaria and often not enough to eat. I was in the troop only because they captured me in the first place. This wasn’t my decision. -- Testimony to Human Rights Watch FORGOTTEN FIGHTERS: Child Soldiers in Angola 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 33 Islington High Street 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9LH UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL (44171) 713-1995 TEL (322) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX (44171) 713-1800 FAX (322) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] April 2003 Vol. 15, No. 10 (A) ANGOLA FORGOTTEN FIGHTERS: Child Soldiers in Angola I. SUMMARY...............................................................................................................................................2 II. RECOMMENDATIONS...........................................................................................................................5 To the Government of Angola .....................................................................................................................5 -

The Angolan Armed Forces and the African Peace and Security Architecture

The Angolan Armed Forces and the African Peace and Security Architecture Luís Manuel Brás Bernardino Lisbon University Institute, Portugal Gustavo Plácido dos Santos Portuguese Institute of International Relations and Security, Portugal Abstract Angola’s involvement in the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) is an example of a rising regional power searching for strategic affirmation. Through a participatory, influential and engaging foreign policy, Angola is committed to a strategic balance in which the Armed Forces (FAA) are an instrument of both military cooperation and conflict resolution within Angola’s area of interest. This article seeks to demystify this paradigm and to reflect upon Angola’s potential interests behind its participation in the APSA’s framework. While being strategic to the development and affirmation of Angola’s military capabilities, the APSA also enables the FAA to function as a mechanism for the assertion of the country’s foreign policy at the regional and continental level. These dynamics are all the more relevant in a context where Luanda holds a non-permanent seat in the United Nations Security Council. “It is equally significant that Angola responded to its post-conflict internal challenges of reconstruction by looking abroad.” Assis Malaquias (2011: 17) Introduction The post-independence conflict in Angola was one of the most violent in the African continent and echoed the main arguments then put forward as endogenous factors behind intra-state conflict in sub-Saharan Africa. It was only after the signing of the Luena Agreement, on 4 April 2002 – which established peace in Angola –, that the country managed to enter the path to development. -

Cabinda Separatism

ANGOLA UPDATE Cabinda separatism Cabinda: a province sandwiched between Congo Brazzaville and the Democratic Republic of Congo Maps: Wikimedia Commons By Inge Amundsen, CMI April 2021 Various separatist movements have been active in the Cabinda enclave in northern Angola since independence. During the 1970s and 80s, the FLEC guerrilla operated a low-intensity guerrilla war, at the same time as government suppression was heavy, due to the importance of Cabinda as an oil- producing province. Although never successful in gaining territory or any significant concessions, the guerrillas gained international attention with an attack on the Togo national football team in 2010, leaving two Togolese and the Angolan bus driver killed. Today, armed resistance seems to be replaced by an upsurge in non-violent protests, at the same time as violent government suppression continues. This indicates that the new president Lourenco and his administration will continue with human rights abuses to keep oil-producing Cabinda under control, despite some reported progress in the right to protest and in freedom of expression at the national level. Background With an area of approximately 7,290 square kilometres, the northern Angolan province of Cabinda is separated from the rest of the country by a 60 kilometres wide strip of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the lower Congo River. Communications with the mainland is therefore difficult, in particular over land. The town of Cabinda is the chief population centre, and the total population is 825,000, according to the latest estimate. Most of the population is Bakongo, and their kin also live in the two other northern regions, Zaire and Uíge, and in the DRC and in the Republic of Congo. -

Soviet-Angolan Relations, 1975-1990 1

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H OCCASIONAL PAPER TITLE : Soviet-Angolan Relations, 1975-199 0 AUTHOR : S . Neil MacFarlan e DATE : March 15, 1992 In accordance with Amendment #6 to Grant #1006-555009, this Occasional Paper by a present or former Council Trustee or contract Awardee has bee n volunteered to the Council by the author for distribution to the Government . NCSEER NOTE This paper consists of Chapter III from Soviet Policy in Africa : from the Old to the New Thinking; George Breslauer Ed. : Published by the Center for Slavic and East European Studies; University of California, Berkeley, for the Berkeley-Stanford Program in Soviet Studies. Forthcoming Spring, 1992. SUMMARY ` This paper supplements two earlier reports by the author, The Evolution of Sovie t Perspectives on Third World Security (distributed on 2/19/92), and The Evolution of Sovie t Perspectives on African Politics (distributed on 3/15/92), and further particularizes hi s analysis by concentrating on Soviet-Angolan relations . A detailed account of those relation s from about 1970 to the late 1980's serves almost as a case study in support of the principa l conclusion of his previous two papers - that the Soviet shift from an aggressively forward , ideological, confrontational and optimistic posture to much the opposite was not tactical, an d not prompted exclusively by extraneous constraints and interests, but was importantly a product of learning from African realities and Soviet experience with them, and is therefore lasting. While already dated and overtaken by larger events, this paper provides not only a useful summary of two critical decades in recent Soviet-Angolan relations, but perhaps also a litmus for Russian Federation policies, including those presumably pursued by Foreig n Minister Andrei Kozyrev in his recent trip to Angola and South Africa . -

Angola Country Report

ANGOLA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Angola October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the document 1.1 2. Geography 2.1 3. Economy 3.1 4. History Post-Independence background since 1975 4.1 Multi-party politics and the 1992 Elections 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.6 Political Situation and Developments in the Civil War September 1999 - February 4.13 2002 End of the Civil War and Political Situation since February 2002 4.19 5. State Structures The Constitution 5.1 Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 Political System 5.9 Presidential and Legislative Election Plans 5.14 Judiciary 5.19 Court Structure 5.20 Traditional Courts 5.23 UNITA - Operated Courts 5.24 The Effect of the Civil War on the Judiciary 5.25 Corruption in the Judicial System 5.28 Legal Documents 5.30 Legal Rights/Detention 5.31 Death Penalty 5.38 Internal Security 5.39 Angolan National Police (ANP) 5.40 Armed Forces of Angola (Forças Armadas de Angola, FAA) 5.43 Prison and Prison Conditions 5.45 Military Service 5.49 Forced Conscription 5.52 Draft Evasion and Desertion 5.54 Child Soldiers 5.56 Medical Services 5.59 HIV/AIDS 5.67 Angola October 2004 People with Disabilities 5.72 Mental Health Treatment 5.81 Educational System 5.82 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues General 6.1 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.5 Newspapers 6.10 Radio and Television 6.13 Journalists 6.18 Freedom of Religion 6.25 Religious Groups 6.28 Freedom of Association and Assembly 6.29 Political Activists – UNITA 6.43