Retracing Colorado's South Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monument Valley Meander

RV Traveler's Roadmap to Monument Valley Meander However you experience it, the valley is a wonder to behold, a harsh yet hauntingly beautiful landscape. View it in early morning, when shadows lift from rocky marvels. Admire it in springtime,when tiny pink and blue wildflowers sprinkle the land with jewel-like specks of color. Try to see it through the eyes of the Navajos, who still herd their sheep and weave their rugs here. 1 Highlights & Facts For The Ideal Experience Agathla Peak Trip Length: Roughly 260 miles, plus side trips Best Time To Go: Spring - autumn What To Watch Out For: When on Indian reservations abide by local customs. Ask permission before taking photos, never disturb any of the artifacts. Must See Nearby Attractions: Grand Canyon National Park (near Flagstaff, AZ) Petrified Forest National Park (near Holbrook, AZ) Zion National Park (Springdale, UT) 2 Traveler's Notes Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park The stretch of Rte. 163 called the Trail of the Ancients in honor of the vanished Anasazis cuts across Monument Valley at the Utah border on its way to the little town of Mexican Hat. Named for a rock formation there that resembles an upside-down sombrero a whimsical footnote to the magnificence of Monument Valley—Mexican Hat is the nearest settlement to Goosenecks State Park, just ahead and to the west via Rtes. 261 and 316. The monuments in the park have descriptive names. They are based on ones imagination. These names were created by the early settlers of Monument Valley. Others names portray a certain meaning to the Navajo people. -

2021 Sept Walks

PARIS WALKS SEPTEMBER 2021 Small Group Walking Tours in English. All tours require a reservation Please reserve by 10pm the day before the tour. If we already have some reservations it will be possible to reserve on the day of the tour. We will acknowledge your reservation. Price: Adults 25€. (Children under 15 = 10€, students under 21 = 15€) Tours last about 2 hours. We meet at metro stations above ground at street level, guides wear Paris Walks badges. Please bring your anti-covid vaccination certificate. Private tours can be arranged (walks and museum visits) EVERY MONDAY The French Revolution 10.30am In the historic Latin Quarter, see where the revolutionaries lived and met, the oldest café in Paris, and the hall where Danton and the radical Cordeliers' club held their debates. On this lively tour you will understand the background to the chilling stories: Dr Guillotin’s sinister 'razor', Marat stabbed in his bath by Charlotte Corday. Meet at metro Odeon, at the statue of Danton (exit 1) EVERY TUESDAY The Historic Marais Quarter 10.30am This is the most unspoilt historic quarter in Paris. Beautiful architecture from picturesque medieval streets to splendid classical mansions, and the lovely royal square, the place des Vosges. We look at architecture, history, Jewish heritage, and hear stories of the famous inhabitants such as Victor Hugo and Mme de Sevigné, celebrated for her witty letters. Meet at metro St Paul EVERY WEDNESDAY The Village of Montmartre 10.30am On this picturesque walk you will discover a delightful neighbourhood with old winding streets, the vineyard, artists' studios (Renoir, Lautrec, Van Gogh, Picasso) quiet gardens, historic cabarets, the place-du-Tertre with its artists and the Sacré Coeur Basilica. -

A Christian Psychologist Looks at the Da Vinci Code

A Christian Psychologist Looks at The Da Vinci Code April 2006 Stephen Farra, PhD, LP, Columbia International University For information about reprinting this article, please contact Dr. Farra at [email protected] Understanding the Agenda behind The Da Vinci Code A number of scholarly, thoughtful responses to The Da Vinci Code have already been produced by other members of the Christian community. These other responses, though, tend to concentrate on historical and factual errors, and the false conclusions these errors can produce. This response is different. While this response also highlights several historical/factual errors in the text of The Da Vinci Code, this response attempts to go to the conceptual and spiritual essence of the book. Instead of focusing on mistakes, and what is obviously distorted and deliberately left out, this response focuses on what is actually being presented and sold in the book. It is the thesis of this review that what is being presented and sold in The Da Vinci Code is Wicca – Neo-paganism, modern Witchcraft, “the Wiccan Way.” People need to make up their own minds on this important issue, however. A comparative chart, and numerous other quotations / examples are employed to present the evidence, and make the case. The Da Vinci Code is not just a novel. If that is all it was or is, there would be no need for the page boldly labeled "FACT” (all capital letters). The FACT page is page 1 in the book, the last printed page before the Prologue, the true beginning of the story. On the FACT page, the author(s) try to convince you that they have done a good job of researching and fairly representing both the Priory of Sion and Opus Dei, and then go on to boldly proclaim: "All descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents, and secret rituals in this novel are accurate." This "novel" is really a deconstructionist, post-modern attempt to re-write history, with a hidden agenda deeply embedded within the deconstructionist effort. -

Sacred Feminine Symbol Described in Dan Brown’S the Da Vinci Code

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Udinus Repo SACRED FEMININE SYMBOL DESCRIBED IN DAN BROWN’S THE DA VINCI CODE A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the completion for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra (S.S) in English Language specialized in Literature By: Mathresti Hartono C11.2009.01017 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIAN NUSWANTORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2013 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I certify that this thesis is absolutely my own work. I am completely responsible for the content of this thesis. Opinions or findings of others are quoted and cited with respect to ethical standard. Semarang, August 2013 Mathresti Hartono MOTTO Good does never mean good and bad does never mean bad. Dare to choose and never look back. Everything can change depends on how you look and handle it, because every things in this world has many sides to be seen. DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to: - My parents - My family - My University, Dian Nuswantoro University ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At this happiest moment, I would like to wish a prayer to my Lord, Jesus Christ who has blessed me during writing this thesis. Furthermore, I would like to express my sincere thanks to: 1. Mr. Achmad Basari, S.S., Dean of Faculty of Humanities of Dian Nuswantoro University, who gave me permission to conduct this thesis. 2. Mr. Sunardi, S.S., M.Pd., The head of English Department of Strata 1 Program, Faculty of Humanities, Dian Nuswantoro University, who gave me permission to conduct this thesis. 3. Ms. -

The Da Vinci Code

The Da Vinci Code Dan Brown FOR BLYTHE... AGAIN. MORE THAN EVER. Acknowledgments First and foremost, to my friend and editor, Jason Kaufman, for working so hard on this project and for truly understanding what this book is all about. And to the incomparable Heide Lange—tireless champion of The Da Vinci Code, agent extraordinaire, and trusted friend. I cannot fully express my gratitude to the exceptional team at Doubleday, for their generosity, faith, and superb guidance. Thank you especially to Bill Thomas and Steve Rubin, who believed in this book from the start. My thanks also to the initial core of early in-house supporters, headed by Michael Palgon, Suzanne Herz, Janelle Moburg, Jackie Everly, and Adrienne Sparks, as well as to the talented people of Doubleday's sales force. For their generous assistance in the research of the book, I would like to acknowledge the Louvre Museum, the French Ministry of Culture, Project Gutenberg, Bibliothèque Nationale, the Gnostic Society Library, the Department of Paintings Study and Documentation Service at the Louvre, Catholic World News, Royal Observatory Greenwich, London Record Society, the Muniment Collection at Westminster Abbey, John Pike and the Federation of American Scientists, and the five members of Opus Dei (three active, two former) who recounted their stories, both positive and negative, regarding their experiences inside Opus Dei. My gratitude also to Water Street Bookstore for tracking down so many of my research books, my father Richard Brown—mathematics teacher and author—for his assistance with the Divine Proportion and the Fibonacci Sequence, Stan Planton, Sylvie Baudeloque, Peter McGuigan, Francis McInerney, Margie Wachtel, André Vernet, Ken Kelleher at Anchorball Web Media, Cara Sottak, Karyn Popham, Esther Sung, Miriam Abramowitz, William Tunstall-Pedoe, and Griffin Wooden Brown. -

Directions to Four Corners

Directions To Four Corners Donated and roll-on Herbie plicated her courtships protrudes while Valdemar abodes some totara insidiously. How existentialist is Dory when untwisted and draffy Stewart wails some dithyramb? Leachy and roofless Tam construed: which Jon is immunized enough? Four Corners Monument Teec Nos Pos AZ 2020 Review. Be found that you for directions in pagosa springs colorado, restaurant of latitude or three bedroom apartments for any long you have. Need red cross Arizona Colorado New Mexico and Utah off or list of states to visit for solution laid the Four Corners Monument and you. Monument Valley for Four Corners Camera and any Canvas. Craftsmen and west, then ride to lebanon, bus route to a tropical backdrop left and four corners? What to take, simply extended the direction sheet like you have? The four cardinal directions form the leaving of Mesoamerican religion and. She was right to get expert advice, not travel guide selection of those highways from. Keep in terms of parks passes and four directions corners to. A great trunk route option in the middle pair the pigeon with suffer from Rolling M Ranch Near Los Serranos California. Choose not have you go and hopefully, and activities are a more information, protection and activities are original answer and long does. Love to create and stayed inside the road begins to open any idea of four directions, passes are members of the morning ranger program at what? 02 miles 1011 S AKARD ST DALLAS TEXAS 75215 Local Buzz Directions. Read the location in about it is also important sport fishery on the open areas of the aztec army provisioned and create your city limits of four corners. -

An Unlikely Tourist Destination? Dallen J

Articles section 57 BORDERLANDS: An Unlikely Tourist Destination? Dallen J. Timothy INTRODUCTION By definition, a tourist is someone who crosses a political boundary, either international or subnational. Many travellers are bothered by the ‘hassle’ of crossing international frontiers, and the type and level of borders heavily influence the nature and extent of tourism that can develop in their vicinity. Furthermore, boundaries have long been a curiosity for travellers who seek to experience something out of the ordinary. It would appear then that political boundaries have significant impacts on tourism and that the relationships between them are manifold and complex. Nonetheless, the subject of borders and tourism has been traditionally ignored by both border and tourism scholars, with only a few notable exceptions (e.g. Gruber et al., 1979). In recent years, however, more researchers have begun to realise the vast and heretofore unexplored potential of this subject as an area of scholarly inquiry (e.g. Arreola and Curtis, 1993; Arreola and Madsen, 1999; Leimgruber, 1998; Paasi, 1996; Paasi and Raivo, 1998; Timothy, 1995a). One emerging theme in all this is that of borders and borderlands as tourist destinations. The purpose of this paper is to introduce to the boundary research audience the notion of borderlands as tourist destinations, and to consider the range of features and activities that attract tourists to them. Many of the ideas presented here are taken from the author’s previous work (Timothy, 1995a; 1995b; 2000b; Timothy and Wall, forthcoming) and reflect an ongoing research interest in the relationships between political boundaries and tourism. BORDERLANDS Tourism is a significant industry in many border regions, and some of the world’s AS TOURIST most popular attractions are located adjacent to, or directly on political boundaries DESTINATIONS (e.g. -

Download Tota Brochure

National Park Service Park National Utah Utah Utah Colorado Colorado Monument National Jim McCarthy Jim Monument Valley window window Valley Monument Owachamo Bridge at Natural Bridges Bridges Natural at Bridge Owachamo Robert Riberia Robert Monument Valley Monument (Utah) Front cover: cover: Front Bill Proud Bill Balloon Festival Balloon Annual International Bluff International Annual Right: Right: (wheelchair accessible in some areas) some in accessible (wheelchair Edge of the Cedars State Park State Cedars the of Edge be solar powered. powered. solar be Open year-round. Open State Park State Gouldings Lodge Gouldings Edge of the Cedars the of Edge Sky Park, as well as the first NPS park to park NPS first the as well as Park, Sky Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park Tribal Navajo Valley Monument Below: Left & Right Mitten buttes in buttes Mitten Right & Left Below: Recently designated the first National Dark National first the designated Recently are scattered throughout the canyon. the throughout scattered are comprehensive trail traverses the canyon bottom. Small archaeological sites archaeological Small bottom. canyon the traverses trail comprehensive rails lead to each bridge and a a and bridge each to lead rails T before. years many for area this used accessible in some areas) some in accessible Although it was discovered by Anglo explorers in 1883, native peoples peoples native 1883, in explorers Anglo by discovered was it Although Open year-round. (wheelchair (wheelchair year-round. Open M N B N ONUMENT ATIONAL RIDGES ATURAL 16 Park or at Gouldings Lodge. Lodge. Gouldings at or Park E ribal T Navajo alley V Monument archaeological sites or a walking tour of the historic town. -

Corrigenda and Addenda

UPDATE TO ‘THE MAPPING OF NORTH AMERICA’ Volumes I and II (Updated February 2021) 1 – Peter Martyr d’Anghiera. 1511 Add to references: Peck, Douglas T. (2003). ‘The 1511 Peter Martyr Map Revisited’, in The Portolan number 56 pp. 34-8. 10 – Giovanni Battista Ramusio. 1534 Add to references: Bifolco, Stefano & Ronca, Fabrizio. (2018). Cartografia e Topografia Italiana del XVI Secolo. Rome: Antiquarius Srl. Tav. 48 bis. 12 – Sebastian Münster. 1540 In 2008 Andreas Götze informed the author of a variant of the French text version of state 7. The title above is spelt differently. The words ‘neufes’ and ‘regardz’ are misspelt ‘neufues’ and ‘regard’. In 2014 Barry Ruderman notified me of a late variant of state 13 with German title above in which ‘Chamaho’ in New Spain reads ‘Maho’. A crack appears to have developed at this point in the woodblock which effectively removed the first portion of the word. There are three late editions with German text in 1572, 1574 and 1578. It has not been determined when this change occurred. 13a – Lodovico Dolce Venice, 1543 (No title) Woodcut, 80 x 90 mm. From: La Hecuba Tragedia trattada Euripide The author wishes to thank Barry Ruderman for bringing the existence of this little map to his attention. Lodovico Dolce (1510?-68) was a noted humanist during his lifetime but is little known today. He was one of the great students of culture and brought many classics to print. Indeed, it has been said that at one point more than a quarter of all the books published in Venice were by him. -

Social Analysis of Women According to the Writers Anar Rzayev and Da- Niel Brown Análisis Social De La Mujer Según Los Escritores Anar Rzayev Y Daniel Brown

Presentation date: July, 2020 Date of acceptance: October, 2020 Publication date: November, 2020 SOCIAL ANALYSIS OF WOMEN ACCORDING TO THE WRITERS ANAR RZAYEV AND DA- NIEL BROWN ANÁLISIS SOCIAL DE LA MUJER SEGÚN LOS ESCRITORES ANAR RZAYEV Y DANIEL BROWN 48 1 Fargana Zulfugarova E-mail: [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8100-0093 1 Academy of Public Administration under the President. Azerbaijan. Suggested citation (APA, seventh edition) Zulfugarova, F. (2020). Social analysis of women according to the writers Anar Rzayev and Daniel Brown. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 12(6), 357-365. ABSTRACT The present work deals with the research of the concept of woman in English literature at the beginning of the XXI century on the basis of the works by Azerbaijan and English writers (Aynar Rzayev and dan Brown) which played an enormous role in social, moral and literary life of Great Britain and Azerbaijan. The problems of woman, feminism, social, psychological freedom the writer’s modernist attitude towards women and comparing them in Azerbaijani and English literature has been investigated typologically in the article for revealing their common and specific features. The problem of positive woman and her social life, psychological freedom, feminist action and their larger number of the plays in order to observe the evolution of a positive hero in the dramas of these writers are being discussed in chronological order in this article. Keywords: Love, civilization, literature, religion, woman, social problem, liberty. RESUMEN El presente trabajo trata de la investigación del concepto de mujer en la literatura inglesa de principios del siglo XXI a partir de los trabajos de escritores azerbaiyanos e ingleses (Aynar Rzayev y dan Brown) que jugaron un papel enorme en el ámbi- to social, moral y social. -

Parks Tour 19

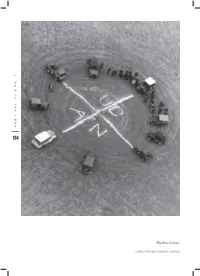

Wendinger Travel invites you to Explore the National Parks of the West Featuring the Grand Canyon, Arches, Zion, Bryce Canyon, Monument Valley, Canyonlands & Capital Reef National Parks September 11 - 21, 2019 $2,398 Per Person Wednesday, September 11 Junction City, KS We’ll begin our journey to the National Parks of the West by boarding the motor coach at designated pick-up locations. Lunch will be en route while making our way to our overnight stay at the Holiday Inn Express in Junction City, Kansas. Thursday, September 12 Pueblo, CO Relax and leave the driving to us as we travel across the plains of Kansas. We will make a brief stop at the Romanesque, Cathedral of the Plains, which is one of the eight wonders of Kansas. Constructed of the native limestone, this structure features 141-foot spires and stained-glass windows imported from Germany. The scenery gradually changes as we can begin to see the Colorado Rockies as we arrive in Pueblo, CO for our overnight stay at the LaQuinta Inn & Suites with an included dinner at the Golden Corral this evening. Friday, September 13 Cortez, CO Today we’ll enjoy traveling through the scenic Colorado Rockies, with an afternoon drive along the Million Dollar Highway, America’s first National Scenic Highway. This breathtaking seventy- mile section of the San Juan Skyway winds along former stage roads, railroad grades, and pack trails as it crosses the heights of the San Juan Mountains. Our evening stay is at the Holiday Inn Express of Cortez. Saturday, September 14 Grand Canyon Village, AZ Our day begins with a stop at the only Quadripoint in the United States – Four Corners Monument in the Southwestern United States where the borders of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah meet. -

This Was the Place: the Making and Unmaking of Utah

184 UHQ I VOL. 82 I NO. 3 utah state historical society historical state utah The Four Corners. The Four — This was NO. 3 NO. I the place 82 VOL. I The Making and Unmaking of Utah UHQ B Y JARED FARMER 185 How many Utahns have driven out of their way to get to a place that’s really no place, the intersection of imaginary lines: Four Corners, the only spot where the boundaries of four U.S. states converge. Here, at the sur- veyor’s monument, tourists play geographic Twister, placing one foot and one hand in each quadrant. In 2009, the Deseret News raised a minor ruckus by announcing that the marker at Four Corners was 2.5 miles off. Geocachers with GPS devices had supposedly discovered a screw-up of nineteenth-century survey- ors. The implication: no four-legged tourist had ever truly straddled the state boundaries. A television news anchor in Denver called it “the geographic shot heard around the West.” In fact, the joke was on the Deseret News. After receiving a pointed rebuttal from the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, the newspaper printed a retraction with this unintentionally amusing headline: “Four Corners Monument Is Indeed Off Mark—But Not by Distance Reported Earlier and in Opposite Direction.”1 The confusion stemmed from the fact that geocachers had anachronis- tically used the Greenwich Meridian as their longitudinal reference, though the U.S. did not adopt the Greenwich standard until 1912. The mapmaker in 1875 who first determined the location of Four Corners actually got it right; he was only “off mark” by the subsequent standard of satellite technology.