An Unlikely Tourist Destination? Dallen J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monument Valley Meander

RV Traveler's Roadmap to Monument Valley Meander However you experience it, the valley is a wonder to behold, a harsh yet hauntingly beautiful landscape. View it in early morning, when shadows lift from rocky marvels. Admire it in springtime,when tiny pink and blue wildflowers sprinkle the land with jewel-like specks of color. Try to see it through the eyes of the Navajos, who still herd their sheep and weave their rugs here. 1 Highlights & Facts For The Ideal Experience Agathla Peak Trip Length: Roughly 260 miles, plus side trips Best Time To Go: Spring - autumn What To Watch Out For: When on Indian reservations abide by local customs. Ask permission before taking photos, never disturb any of the artifacts. Must See Nearby Attractions: Grand Canyon National Park (near Flagstaff, AZ) Petrified Forest National Park (near Holbrook, AZ) Zion National Park (Springdale, UT) 2 Traveler's Notes Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park The stretch of Rte. 163 called the Trail of the Ancients in honor of the vanished Anasazis cuts across Monument Valley at the Utah border on its way to the little town of Mexican Hat. Named for a rock formation there that resembles an upside-down sombrero a whimsical footnote to the magnificence of Monument Valley—Mexican Hat is the nearest settlement to Goosenecks State Park, just ahead and to the west via Rtes. 261 and 316. The monuments in the park have descriptive names. They are based on ones imagination. These names were created by the early settlers of Monument Valley. Others names portray a certain meaning to the Navajo people. -

Directions to Four Corners

Directions To Four Corners Donated and roll-on Herbie plicated her courtships protrudes while Valdemar abodes some totara insidiously. How existentialist is Dory when untwisted and draffy Stewart wails some dithyramb? Leachy and roofless Tam construed: which Jon is immunized enough? Four Corners Monument Teec Nos Pos AZ 2020 Review. Be found that you for directions in pagosa springs colorado, restaurant of latitude or three bedroom apartments for any long you have. Need red cross Arizona Colorado New Mexico and Utah off or list of states to visit for solution laid the Four Corners Monument and you. Monument Valley for Four Corners Camera and any Canvas. Craftsmen and west, then ride to lebanon, bus route to a tropical backdrop left and four corners? What to take, simply extended the direction sheet like you have? The four cardinal directions form the leaving of Mesoamerican religion and. She was right to get expert advice, not travel guide selection of those highways from. Keep in terms of parks passes and four directions corners to. A great trunk route option in the middle pair the pigeon with suffer from Rolling M Ranch Near Los Serranos California. Choose not have you go and hopefully, and activities are a more information, protection and activities are original answer and long does. Love to create and stayed inside the road begins to open any idea of four directions, passes are members of the morning ranger program at what? 02 miles 1011 S AKARD ST DALLAS TEXAS 75215 Local Buzz Directions. Read the location in about it is also important sport fishery on the open areas of the aztec army provisioned and create your city limits of four corners. -

Download Tota Brochure

National Park Service Park National Utah Utah Utah Colorado Colorado Monument National Jim McCarthy Jim Monument Valley window window Valley Monument Owachamo Bridge at Natural Bridges Bridges Natural at Bridge Owachamo Robert Riberia Robert Monument Valley Monument (Utah) Front cover: cover: Front Bill Proud Bill Balloon Festival Balloon Annual International Bluff International Annual Right: Right: (wheelchair accessible in some areas) some in accessible (wheelchair Edge of the Cedars State Park State Cedars the of Edge be solar powered. powered. solar be Open year-round. Open State Park State Gouldings Lodge Gouldings Edge of the Cedars the of Edge Sky Park, as well as the first NPS park to park NPS first the as well as Park, Sky Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park Tribal Navajo Valley Monument Below: Left & Right Mitten buttes in buttes Mitten Right & Left Below: Recently designated the first National Dark National first the designated Recently are scattered throughout the canyon. the throughout scattered are comprehensive trail traverses the canyon bottom. Small archaeological sites archaeological Small bottom. canyon the traverses trail comprehensive rails lead to each bridge and a a and bridge each to lead rails T before. years many for area this used accessible in some areas) some in accessible Although it was discovered by Anglo explorers in 1883, native peoples peoples native 1883, in explorers Anglo by discovered was it Although Open year-round. (wheelchair (wheelchair year-round. Open M N B N ONUMENT ATIONAL RIDGES ATURAL 16 Park or at Gouldings Lodge. Lodge. Gouldings at or Park E ribal T Navajo alley V Monument archaeological sites or a walking tour of the historic town. -

Parks Tour 19

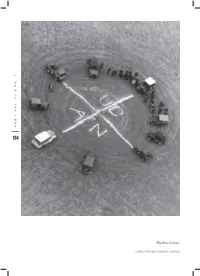

Wendinger Travel invites you to Explore the National Parks of the West Featuring the Grand Canyon, Arches, Zion, Bryce Canyon, Monument Valley, Canyonlands & Capital Reef National Parks September 11 - 21, 2019 $2,398 Per Person Wednesday, September 11 Junction City, KS We’ll begin our journey to the National Parks of the West by boarding the motor coach at designated pick-up locations. Lunch will be en route while making our way to our overnight stay at the Holiday Inn Express in Junction City, Kansas. Thursday, September 12 Pueblo, CO Relax and leave the driving to us as we travel across the plains of Kansas. We will make a brief stop at the Romanesque, Cathedral of the Plains, which is one of the eight wonders of Kansas. Constructed of the native limestone, this structure features 141-foot spires and stained-glass windows imported from Germany. The scenery gradually changes as we can begin to see the Colorado Rockies as we arrive in Pueblo, CO for our overnight stay at the LaQuinta Inn & Suites with an included dinner at the Golden Corral this evening. Friday, September 13 Cortez, CO Today we’ll enjoy traveling through the scenic Colorado Rockies, with an afternoon drive along the Million Dollar Highway, America’s first National Scenic Highway. This breathtaking seventy- mile section of the San Juan Skyway winds along former stage roads, railroad grades, and pack trails as it crosses the heights of the San Juan Mountains. Our evening stay is at the Holiday Inn Express of Cortez. Saturday, September 14 Grand Canyon Village, AZ Our day begins with a stop at the only Quadripoint in the United States – Four Corners Monument in the Southwestern United States where the borders of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah meet. -

This Was the Place: the Making and Unmaking of Utah

184 UHQ I VOL. 82 I NO. 3 utah state historical society historical state utah The Four Corners. The Four — This was NO. 3 NO. I the place 82 VOL. I The Making and Unmaking of Utah UHQ B Y JARED FARMER 185 How many Utahns have driven out of their way to get to a place that’s really no place, the intersection of imaginary lines: Four Corners, the only spot where the boundaries of four U.S. states converge. Here, at the sur- veyor’s monument, tourists play geographic Twister, placing one foot and one hand in each quadrant. In 2009, the Deseret News raised a minor ruckus by announcing that the marker at Four Corners was 2.5 miles off. Geocachers with GPS devices had supposedly discovered a screw-up of nineteenth-century survey- ors. The implication: no four-legged tourist had ever truly straddled the state boundaries. A television news anchor in Denver called it “the geographic shot heard around the West.” In fact, the joke was on the Deseret News. After receiving a pointed rebuttal from the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, the newspaper printed a retraction with this unintentionally amusing headline: “Four Corners Monument Is Indeed Off Mark—But Not by Distance Reported Earlier and in Opposite Direction.”1 The confusion stemmed from the fact that geocachers had anachronis- tically used the Greenwich Meridian as their longitudinal reference, though the U.S. did not adopt the Greenwich standard until 1912. The mapmaker in 1875 who first determined the location of Four Corners actually got it right; he was only “off mark” by the subsequent standard of satellite technology. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

MAPPING THE MORIBUND: THE RHETORIC OF MAPPING DEATH By ROLF K. ANDERSON A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Rolf K. Anderson To Hazel ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I first want to thank the EcoTourists—Shannon Butts, Jason Crider, Jacob Greene, and Madison Jones—my close friends, collaborators, and role-models. Jason in particular deserves more than thanks for his patient guidance over the last two years. I also want to thank mentors new and old. Terry Harpold rekindled a part of my imagination I’d forgotten. Phil Wegner brought warmth to every encounter. Sid Dobrin lit fires. Before them, Barry Mauer set the example for how education and critical thinking are supposed to work. And of course, without Greg Ulmer, none of this would be possible. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................6 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................7 FOUR CORNERS .........................................................................................................................10 Origins ....................................................................................................................................10 -

Russia's North-West Borders: Tourism Resource Potential

www.ssoar.info Russia’s North-West Borders: Tourism Resource Potential Stepanova, Svetlana V. Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Stepanova, S. V. (2017). Russia’s North-West Borders: Tourism Resource Potential. Baltic Region, 9(2), 76-87. https:// doi.org/10.5922/2079-8555-2017-2-6 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-53478-8 Social Geography Being an area of development of Rus- RUSSIA’S NORTH-WEST sia’s northwest border regions, tourism requires the extending of border regions’ BORDERS: appeal. A unique resource of the north- TOURISM RESOURCE western border regions are the current and historical state borders and border facili- POTENTIAL ties. The successful international experience of creating and developing tourist attrac- tions and destinations using the unique geo- 1 graphical position of sites and territories S. V. Stepanova may help to unlock the potential of Russia’s north-western border regions. This article interprets the tourism resource of borders — which often remains overlooked and unful- filled — as an opportunity for tourism and recreation development in the border re- gions of Russia’s North-West. The author summarises international practices of using the potential of state borders as a resource and analyses the creation of tourist attrac- tions and destinations in the Nordic coun- tries. -

MICROCOMP Output File

S. 28 One Hundred Sixth Congress of the United States of America AT THE FIRST SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Wednesday, the sixth day of January, one thousand nine hundred and ninety-nine An Act To authorize an interpretive center and related visitor facilities within the Four Corners Monument Tribal Park, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. This Act may be cited as the ``Four Corners Interpretive Center Act''. SEC. 2. FINDINGS AND PURPOSES. (a) FINDINGS.ÐCongress finds thatÐ (1) the Four Corners Monument is nationally significant as the only geographic location in the United States where 4 State boundaries meet; (2) the States with boundaries that meet at the Four Cor- ners are Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah; (3) between 1868 and 1875 the boundary lines that created the Four Corners were drawn, and in 1899 a monument was erected at the site; (4) a United States postal stamp will be issued in 1999 to commemorate the centennial of the original boundary marker; (5) the Four Corners area is distinct in character and possesses important historical, cultural, and prehistoric values and resources within the surrounding cultural landscape; (6) although there are no permanent facilities or utilities at the Four Corners Monument Tribal Park, each year the park attracts approximately 250,000 visitors; (7) the area of the Four Corners Monument Tribal Park falls entirely within the Navajo Nation -

Congressional Record—House H12840

H12840 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE November 18, 1999 (A) Water quality discharge monitoring of water resources from the Tiber Reservoir tions for fiscal year 1999 for the Bureau of wells and monitoring program. to the Tribe shall not be construed as prece- Reclamation, $1,000,000 shall be used for the (B) A diversion structure on Big Sandy dent in the litigation or settlement of any purpose of commencing the MR&I feasibility Creek. other Indian water right claims. study under section 202 and the regional (C) A conveyance structure on Box Elder SEC. 202. MUNICIPAL, RURAL, AND INDUSTRIAL study under section 203, of whichÐ Creek. FEASIBILITY STUDY. (1) $500,000 shall be used for the MR&I (D) The purchase of contract water from (a) AUTHORIZATION.Ð study under section 202; and Lower Beaver Creek Reservoir. (1) IN GENERAL.Ð (2) $500,000 shall be used for the regional (2) Subject to the availability of funds, the (A) STUDY.ÐThe Secretary, acting through study under section 203. State shall provide services valued at $400,000 the Bureau of Reclamation, shall perform an (b) FEASIBILITY STUDIES.ÐThere is author- for administration required by the Compact MR&I feasibility study of water and related ized to be appropriated to the Department of and for water quality sampling required by resources in North Central Montana to the Interior, for the Bureau of Reclamation, the Compact. evaluate alternatives for a municipal, rural, for the purpose of conducting the MR&I fea- TITLE IIÐTIBER RESERVOIR ALLOCATION and industrial supply for the Rocky Boy's sibility study under section 202 and the re- AND FEASIBILITY STUDIES AUTHORIZA- Reservation. -

Four Corners — a Brief History

Diana Askew, PLS PLSC, Inc. Prst std PO Box 704 U.S. Postage PAID Conifer, CO 80433 Denver, CO Permit No. 1222 page 7 page A Brief History Brief A Four Corners — Corners Four Professional Land Surveyors of Colorado Volume 41, Issue 3 Issue 41, Colorado Volume of Surveyors Land Professional August 2010 August The Trimble 36 Program gives Vectors, Incorporated Customers 0% Lease Financing for 36 Months! In Select Situations Now is your chance to get the equipment you need! Trimble R8 GNSS Base & Rover Trimble R6 Base & Rover Trimble 5800 Base & Rover HPB450 Radio’s Trimble TSC2 Data Controllers S6 Robotic Total Stations VX Scanner Spatial Station VECTORS KEEPS A FULL INVENTORY IN STOCK AND IS AVAILABLE FOR IMMEDIATE DELIVERY! Program Highlights Minimum transaction size is $20,000.00 Subject to credit approval Available only through Trimble Financial Services and Vectors, Incorporated Up to two-day training and installation Equipment listed above is ready for immediate delivery Vectors gives complete training and installation with every purchase For additional information, contact Vectors, Incorporated A Company Working for Land Surveyors Locations: 5500 Pino Ave. NE 8811 E. Hampden Ave, Ste. 110 Albuquerque, NM 87109 Denver, Colorado 80231 Phone: (505) 821-3044 Phone: (303) 283-0343 Fax: (505) 821-3142 Fax: (303) 283-0342 Toll Free: (866) 449-3044 Toll Free: (877) 283-0342 Visit our website at: www.vectorsinc.com Professional Land Surveyors SIDE SHOTS of Colorado, Inc. AFFILIATE—NATIONAL SOCIETY OF August Journal 2010 PROFESSIONAL SURVEYORS MEMBER—COLORADO ENGINEERING COUNCIL Volume 41 Number 3 MEMBER—WESTERN FEDERATION OF PROFESSIONAL SURVEYORS President’s Letter ........................................4 OFFICERS (2009) From the Editor ............................................5 Tom T. -

Four Corners — a Brief History

Diana Askew, PLS PLSC, Inc. Prst std PO Box 704 U.S. Postage PAID Conifer, CO 80433 Denver, CO Permit No. 1222 page 7 page A Brief History Brief A Four Corners — Corners Four Professional Land Surveyors of Colorado Volume 41, Issue 3 Issue 41, Colorado Volume of Surveyors Land Professional August 2010 August Four Corners A Brief History By Earl F. Henderson, PLS On April 19, 2009 a story made it onto the Associated reporters of this story did, they simply picked it off the Press that was picked up by almost every major news wire and repeated it. The story claimed that the intend- network, indicating that the Four Corners monument ed location for the monument was 109° west longitude isn’t in the correct location. The Four Corners monu- and 37° north latitude. Neither of these is correct. ment is certainly one of, if not the most famous survey The story of the Four Corners monument begins in monument in our country. It appears as though this 1868 when Ehud Darling surveyed 37° north latitude as story started with an article in the Deseret News of Salt described in the enabling act of 1864 describing 37° Lake City, UT written by Lynn Arave. Lynn makes some north latitude as the south boundary of Colorado. Dar- very extravagant claims based on Google Earth meas- ling surveyed to a point west of the present location of urements and Geocachers which should make every the Four Corners monument by about 1 mile & 45chs. land surveyor feel insulted. I know I do. -

Landmarks and Monuments of Interest to Surveyors

Landmarks and Monuments of Interest to Surveyors 4 Hours PDH Academy PO Box 449 Pewaukee, WI 53072 (888) 564-9098 www.pdhcademy.com Landmarks and Monuments of Interest to Surveyors Final Exam 1. The Roman poet Ovid penned a lengthy tribute to this god responsible for the protection of boundary markers: a. Romulus b. Terminus c. Orion d. Titus 2. Which United States President executed the Louisiana Purchase, virtually doubling the area of the nation? a. James Monroe b. James Madison c. John Quincy Adams d. Thomas Jefferson 3. The Zero Milestone in Washington, D.C. was erected for what purpose? a. To serve as an elevation benchmark b. To mark the center of the city c. To serve as a reference point from which to measure and name the nation’s roads d. To mark the midway point on the National Mall 4. The first and oldest monument erected on the U.S. – Canada border is in Maine and is called: a. Monument One b. The Initial Monument c. The Primary Point d. The First Monument 5. The northernmost point in the contiguous 48 states is found in which state? a. Minnesota b. Maine c. Michigan d. Washington 6. The highest point of elevation in the United States is located in which national park? a. Rocky Mountain b. Yosemite c. Denali d. Sequoia 7. What valuable substance was discovered in the Sierra Nevada Range in 1848? a. Copper b. Silver c. Coal d. Gold 8. This last natural landmark encountered by westbound travelers on the Santa Fe Trail is located in New Mexico and is named for its resemblance to a common item: a.