3.0 Affected Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narbonapass.Pdf

FIRST-DAY ROAD LOG 1 FIRST-DAY ROAD LOG, FROM GALLUP TO GAMERCO, YAH-TA-HEY, WINDOW ROCK, FORT DEFIANCE, NAVAJO, TODILTO PARK, CRYSTAL, NARBONA PASS, SHEEP SPRINGS, TOHATCHI AND GALLUP SPENCER G. LUCAS, STEVEN C. SEMKEN, ANDREW B. HECKERT, WILLIAM R. BERGLOF, First-day Road Log GRETCHEN HOFFMAN, BARRY S. KUES, LARRY S. CRUMPLER AND JAYNE C. AUBELE ������ ������ ������ ������� ������ ������ ������ ������ �������� Distance: 141.8 miles ������� Stops: 5 ���� ������ ������ SUMMARY ������ �� ������ �� ����� �� The first day’s trip takes us around the southern �� �� flank of the Defiance uplift, back over it into the �� southwestern San Juan Basin and ends at the Hogback monocline at Gallup. The trip emphasizes Mesozoic— especially Jurassic—stratigraphy and sedimentation in NOTE: Most of this day’s trip will be conducted the Defiance uplift region. We also closely examine within the boundaries of the Navajo (Diné) Nation under Cenozoic volcanism of the Navajo volcanic field. a permit from the Navajo Nation Minerals Department. Stop 1 at Window Rock discusses the Laramide Persons wishing to conduct geological investigations Defiance uplift and introduces Jurassic eolianites near on the Navajo Nation, including stops described in this the preserved southern edge of the Middle-Upper guidebook, must first apply for and receive a permit Jurassic depositional basin. At Todilto Park, Stop 2, from the Navajo Nation Minerals Department, P.O. we examine the type area of the Jurassic Todilto For- Box 1910, Window Rock, Arizona, 86515, 928-871- mation and discuss Todilto deposition and economic 6587. Sample collection on Navajo land is forbidden. geology, a recurrent theme of this field conference. From Todilto Park we move on to the Green Knobs diatreme adjacent to the highway for Stop 3, and then to Stop 4 at the Narbona Pass maar at the crest of the Chuska Mountains. -

Monument Valley Meander

RV Traveler's Roadmap to Monument Valley Meander However you experience it, the valley is a wonder to behold, a harsh yet hauntingly beautiful landscape. View it in early morning, when shadows lift from rocky marvels. Admire it in springtime,when tiny pink and blue wildflowers sprinkle the land with jewel-like specks of color. Try to see it through the eyes of the Navajos, who still herd their sheep and weave their rugs here. 1 Highlights & Facts For The Ideal Experience Agathla Peak Trip Length: Roughly 260 miles, plus side trips Best Time To Go: Spring - autumn What To Watch Out For: When on Indian reservations abide by local customs. Ask permission before taking photos, never disturb any of the artifacts. Must See Nearby Attractions: Grand Canyon National Park (near Flagstaff, AZ) Petrified Forest National Park (near Holbrook, AZ) Zion National Park (Springdale, UT) 2 Traveler's Notes Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park The stretch of Rte. 163 called the Trail of the Ancients in honor of the vanished Anasazis cuts across Monument Valley at the Utah border on its way to the little town of Mexican Hat. Named for a rock formation there that resembles an upside-down sombrero a whimsical footnote to the magnificence of Monument Valley—Mexican Hat is the nearest settlement to Goosenecks State Park, just ahead and to the west via Rtes. 261 and 316. The monuments in the park have descriptive names. They are based on ones imagination. These names were created by the early settlers of Monument Valley. Others names portray a certain meaning to the Navajo people. -

The Uranium Deposits of Northeastern Arizona William L

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/24 The uranium deposits of northeastern Arizona William L. Chenoweth and Roger C. Malan, 1973, pp. 139-149 in: Monument Valley (Arizona, Utah and New Mexico), James, H. L.; [ed.], New Mexico Geological Society 24th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 232 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1973 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

2016 Arizona Shade Tree Planting Prioritization ATLAS

2016 Shade Tree Planting Prioritization 1 Urban and Community Forestry 2016 Arizona Shade Tree Planting Prioritization ATLAS Planning Maps for the Department of Forestry and Fire Management 2016 Shade Tree Planting Prioritization Atlas About the 2016 Shade Tree Planting Prioritization Atlas This collection of maps summarizes the results of the 2016 Shade Tree Planting Prioritization analysis of the Urban and Community Forestry Program (UCF) at the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management (DFFM). The purpose of the analysis was to assess existing urban forests in Arizona’s communities and identify shade tree planting needs. The spatial analysis, based on U.S. Census Block Group polygons, generated seven sub-indices for criteria identified by an expert panel: population density, lack of canopy cover, low-income, traffic proximity, sustainability, air quality, and urban heat effect. The seven sub-indices were combined into one Shade Tree Planting Priority Index and further summarized into a Shade Tree Planting Priority Ranking. The resulting reports, maps, and GIS data provide compiled information that can be easily used for identifying areas for strategic shade tree planting within a community or across Arizona’s major cities and towns. These maps provide limited detail for conveying the scale and depth of the analysis results which – for more detailed use – are best explored through the analysis report, interactive maps, and the GIS data available through the UCF Program webpage at https://forestryandfire.az.gov/forestry-community-forestry/urban-community-forestry/projects. Note: At the time of publication, two known analysis area errors have been identified. A few of Safford’s incorporated easements were not captured correctly. -

USGS Open-File Report 2009-1269, Appendix 1

Appendix 1. Summary of location, basin, and hydrological-regime characteristics for U.S. Geological Survey streamflow-gaging stations in Arizona and parts of adjacent states that were used to calibrate hydrological-regime models [Hydrologic provinces: 1, Plateau Uplands; 2, Central Highlands; 3, Basin and Range Lowlands; e, value not present in database and was estimated for the purpose of model development] Average percent of Latitude, Longitude, Site Complete Number of Percent of year with Hydrologic decimal decimal Hydrologic altitude, Drainage area, years of perennial years no flow, Identifier Name unit code degrees degrees province feet square miles record years perennial 1950-2005 09379050 LUKACHUKAI CREEK NEAR 14080204 36.47750 109.35010 1 5,750 160e 5 1 20% 2% LUKACHUKAI, AZ 09379180 LAGUNA CREEK AT DENNEHOTSO, 14080204 36.85389 109.84595 1 4,985 414.0 9 0 0% 39% AZ 09379200 CHINLE CREEK NEAR MEXICAN 14080204 36.94389 109.71067 1 4,720 3,650.0 41 0 0% 15% WATER, AZ 09382000 PARIA RIVER AT LEES FERRY, AZ 14070007 36.87221 111.59461 1 3,124 1,410.0 56 56 100% 0% 09383200 LEE VALLEY CR AB LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.50204 1 9,440e 1.3 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383220 LEE VALLEY CREEK TRIBUTARY 15020001 33.93894 109.50204 1 9,440e 0.5 6 0 0% 49% NEAR GREER, ARIZ. 09383250 LEE VALLEY CR BL LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.49787 1 9,400e 1.9 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383400 LITTLE COLORADO RIVER AT GREER, 15020001 34.01671 109.45731 1 8,283 29.1 22 22 100% 0% ARIZ. -

Hydrogeology of the Chinle Wash Watershed, Navajo Nation Arizona, Utah and New Mexico

Hydrogeology of the Chinle Wash Watershed, Navajo Nation Arizona, Utah and New Mexico Item Type Thesis-Reproduction (electronic); text Authors Roessel, Raymond J. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 19:50:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/191379 HYDROGEOLOGY OF THE CHINLE WASH WATERSHED, NAVAJO NATION, ARIZONA, UTAH AND NEW MEXICO by Raymond J. Roessel A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HYDROLOGY AND WATER RESOURCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE WITH A MAJOR IN HYDROLOGY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1994 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

MS4 Route Mapping PRIORITIZATION PARAMETERS

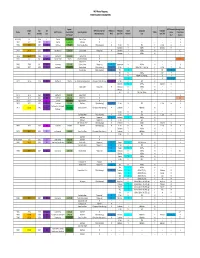

MS4 Route Mapping PRIORITIZATION PARAMETERS Approx. ADOT Named or Average Annual Length Year Age OAW/Impaired/ Not‐ Within 1/4 Pollutants ADOT Designated Pollutants Route ADOT Districts Annual Traffic Receiving Waters TMDL? Given Precipitation (mi) Installed (yrs) Attaining Waters? Mile? (per EPA) Pollutant? Uses (per EPA) (Vehicles/yr) WLA? (inches) SR 24 (802) 1.0 2014 5 Central 11,513,195 Queen Creek N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 6 SR 51 16.7 1987 32 Central 61,081,655 Salt River N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 6 SR 61 76.51 1935 84 Northeast 775,260 Little Colorado River Y (Not attaining) N E. Coli N FBC Y E. Coli N 7 Sediment Y A&Wc Y Sediment N SR 64 108.31 1932 87 Northcentral 2,938,250 Colorado River Y (Impaired) N Sediment Y A&Wc N ‐‐ ‐‐ 8.5 Selenium Y A&Wc N ‐‐ ‐‐ SR 66 66.59 1984 35 Northwest 5,154,530 Truxton Wash N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 7 SR 67 43.4 1941 78 Northcentral 39,055 House Rock Wash N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 17 Kanab Creek N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ SR 68 27.88 1941 78 Northwest 5,557,490 Colorado River Y (Impaired) Y Temperature N A&Ww N ‐‐ ‐‐ 6 SR 69 33.87 1938 81 Northwest 17,037,470 Granite Creek Y (Not attaining) Y E. Coli N A&Wc, FBC, FC, AgI, AgL Y E. Coli Y 9.5 Watson Lake Y (Not attaining) Y TN Y ‐‐ Y TN Y DO N A&Ww Y DO Y pH N A&Ww, FBC, AgI, AgL Y pH Y TP Y ‐‐ Y TP Y SR 71 24.16 1936 83 Northwest 296,015 Sols Wash/Hassayampa River Y (Impaired, Not attaining) Y E. -

Index 1 INDEX

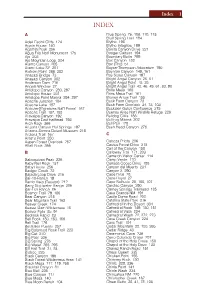

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

Tse' Nikani Draft Corridor Management

Tse'nikani Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan DRAFT August 2013 Introduction Purpose Tse’nikani Scenic Byway was established The purpose of a byway corridor as an Arizona Byway in 2005 and given the management plan is not to create more name Tse’nikani ‘Flat Mesa Rock’ Scenic regulations or taxes. Rather, a corridor Byway. management plan documents the goals, strategies, and responsibilities for preserving and enhancing the byway’s most Byway Description valuable qualities. Promoting tourism can Tse’nikani Scenic Byway, U.S. Highway be one target, but so are issues of safety or (US) 191 is located in northeast Arizona preserving historic or cultural structures. in Apache County and entirely within the 160 The Corridor Management Plan can: Navajo Nation. The portion of US 191 that 1 160 Tse’nikani is a designated Arizona Scenic Byway is Scenic Road ◊ document community interest from Milepost (MP) 467.0, south of Many ◊ document existing conditions and Farms, to MP 510.4, at the junction with history US 160, near Mexican Water. The highway ◊ guide enhancement and safety is the primary route to access Canyon de improvement projects ARIZONA Chelly National Monument, about 13 miles mexico new south of the south end of the byway. ◊ promote partnerships for conservation Chinle and enhancement activities US 191 is a two-lane asphalt paved road for ◊ suggest resources for project development almost its entire length with no median and programs and few left-turn lanes. The roadway is ◊ promote coordination between residents, managed by the Arizona Department communities, and agencies of Transportation (ADOT) through the 264 Ganado ◊ support application for National Scenic Navajo Nation. -

Eimeria Sciurorum (Apicomplexa, Coccidia) from the Calabrian Black Squirrel (Sciurus Meridionalis): an Example of Lower Host Specificity of Eimerians

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT published: 28 July 2020 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00369 Eimeria sciurorum (Apicomplexa, Coccidia) From the Calabrian Black Squirrel (Sciurus meridionalis): An Example of Lower Host Specificity of Eimerians Jana Kvicerova 1*, Lada Hofmannova 2, Francesca Scognamiglio 3 and Mario Santoro 4 1 Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Ceskéˇ Budejovice,ˇ Czechia, 2 Department of Pathology and Parasitology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences Brno, Brno, Czechia, 3 Department of Animal Health, Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale del Mezzogiorno, Portici, Italy, 4 Department of Integrative Marine Ecology, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Naples, Italy Edited by: Arvo Viltrop, Host specificity plays one of the key roles in parasitism. It affects the evolution and Estonian University of Life Sciences, Estonia diversification of both host and parasite, as well as it influences their geographical Reviewed by: distribution, and epidemiological significance. For most of parasites, however, host Phoebe Chapman, specificity is unknown or misrepresented because it is difficult to be determined The University of accurately. Here we provide the information about the lower host specificity of Eimeria Queensland, Australia Colin James McInnes, sciurorum infecting squirrels, and its new host record for the Calabrian black squirrel Moredun Research Institute, Sciurus meridionalis, a southern Italian endemic species. United Kingdom *Correspondence: Keywords: squirrels, coccidia, host specificity, endemic species, parasite dispersal, southern Italy Jana Kvicerova [email protected] INTRODUCTION Specialty section: This article was submitted to The host specificity of a parasite—the degree to which the parasite is adapted to its host/s, and the Zoological Medicine, number of host species that can successfully be used by the parasite—is the result of a long-term a section of the journal adaptation process undergone by both the host and the parasite (1, 2). -

ABSTRACTS BOOK Proof 03

1st – 15th December ! 1st International Meeting of Early-stage Researchers in Paleontology / XIV Encuentro de Jóvenes Investigadores en Paleontología st (1December IMERP 1-stXIV-15th EJIP), 2018 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Palaeontology in the virtual era 4 1st – 15th December ! Ist Palaeontological Virtual Congress. Book of abstracts. Palaeontology in a virtual era. From an original idea of Vicente D. Crespo. Published by Vicente D. Crespo, Esther Manzanares, Rafael Marquina-Blasco, Maite Suñer, José Luis Herráiz, Arturo Gamonal, Fernando Antonio M. Arnal, Humberto G. Ferrón, Francesc Gascó and Carlos Martínez-Pérez. Layout: Maite Suñer. Conference logo: Hugo Salais. ISBN: 978-84-09-07386-3 5 1st – 15th December ! Palaeontology in the virtual era BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 6 4 PRESENTATION The 1st Palaeontological Virtual Congress (1st PVC) is just the natural consequence of the evolution of our surrounding world, with the emergence of new technologies that allow a wide range of communication possibilities. Within this context, the 1st PVC represents the frst attempt in palaeontology to take advantage of these new possibilites being the frst international palaeontology congress developed in a virtual environment. This online congress is pioneer in palaeontology, offering an exclusively virtual-developed environment to researchers all around the globe. The simplicity of this new format, giving international projection to the palaeontological research carried out by groups with limited economic resources (expensive registration fees, travel, accomodation and maintenance expenses), is one of our main achievements. This new format combines the benefts of traditional meetings (i.e., providing a forum for discussion, including guest lectures, feld trips or the production of an abstract book) with the advantages of the online platforms, which allow to reach a high number of researchers along the world, promoting the participation of palaeontologists from developing countries. -

(NTUA) – Navajo Townsite NPDES Permit No

December 2011 FACT SHEET Authorization to Discharge under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System for the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority (NTUA) – Navajo Townsite NPDES Permit No. NN0030335 Applicant address: Navajo Tribal Utility Authority (“NTUA”) P.O. Box 587 Fort Defiance, Arizona 86504 Applicant Contact: Harry L. Begaye, Technical Assistant (928) 729-6208 Facility Address: 0.5 miles west of Navajo Pine High School West of Black Creek Wash in Navajo, NM Facility Contact: Philemon Allison, District Manager (928) 729-6140 I. Summary The NTUA was issued a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (“NPDES”) Permit (No. NN0030335) on December 23, 2006, for its Navajo Townsite wastewater treatment lagoon facility (“WWTF”), pursuant to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (“U.S. EPA”) regulations set forth in Title 40, Code of Federal Regulations (“CFR”) Part 122.21. The permit was effective December 23, 2006, through midnight, December 22, 2011. NTUA applied to U.S. EPA Region 9 for reissuance on August 16, 2011. This fact sheet is based on information provided by the applicant through its application and discharge data submittal, along with the appropriate laws and regulations. Pursuant to Section 402 of the Clean Water Act (“CWA”), the U.S. EPA is proposing issuance of the NPDES permit renewal to NTUA Navajo Townsite (“permittee”) for the discharge of treated domestic wastewater to receiving waters named Black Creek, a tributary to Puerco River, an eventual tributary to the Little Colorado River, a water of the United States. II. Description of Facility The NTUA Navajo Townsite wastewater treatment lagoons are located 0.5 miles west of Navajo Pine High School, west of Black Creek Wash in Navajo New Mexico.