University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monument Valley Meander

RV Traveler's Roadmap to Monument Valley Meander However you experience it, the valley is a wonder to behold, a harsh yet hauntingly beautiful landscape. View it in early morning, when shadows lift from rocky marvels. Admire it in springtime,when tiny pink and blue wildflowers sprinkle the land with jewel-like specks of color. Try to see it through the eyes of the Navajos, who still herd their sheep and weave their rugs here. 1 Highlights & Facts For The Ideal Experience Agathla Peak Trip Length: Roughly 260 miles, plus side trips Best Time To Go: Spring - autumn What To Watch Out For: When on Indian reservations abide by local customs. Ask permission before taking photos, never disturb any of the artifacts. Must See Nearby Attractions: Grand Canyon National Park (near Flagstaff, AZ) Petrified Forest National Park (near Holbrook, AZ) Zion National Park (Springdale, UT) 2 Traveler's Notes Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park The stretch of Rte. 163 called the Trail of the Ancients in honor of the vanished Anasazis cuts across Monument Valley at the Utah border on its way to the little town of Mexican Hat. Named for a rock formation there that resembles an upside-down sombrero a whimsical footnote to the magnificence of Monument Valley—Mexican Hat is the nearest settlement to Goosenecks State Park, just ahead and to the west via Rtes. 261 and 316. The monuments in the park have descriptive names. They are based on ones imagination. These names were created by the early settlers of Monument Valley. Others names portray a certain meaning to the Navajo people. -

Rhetorical Gardening: Greening Composition

Rhetorical Gardening: Greening Composition A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School Of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences by Carla Sarr June 2017 Master of Science in Teaching and Secondary Education, The New School Committee Chair: Laura R. Micciche Abstract Rhetorical Gardening: Greening Composition argues that the rhetorical understanding of landscapes offers a material site and a metaphor by which to broaden our understanding of rhetoric and composition, as well as increasing the rhetorical archive and opportunities for scholarship. An emphasis on material place in composition is of particular value as sustainability issues are among the toughest challenges college students will face in the years to come. Reading landscapes is an interpretive act central to meaningful social action. The dissertation argues that existing work in rhetorical theory and composition pedagogy has set the stage for an ecological turn in composition. Linking ecocomposition, sustainability, cultural geography, and literacy pedagogies, I trace the origins of my belief that the next manifestation of composition pedagogy is material, embodied, place-based, and firmly planted in the literal issues resulting from climate change. I draw upon historical gardens, landscapes composed by the homeless, community, commercial, and guerilla gardens to demonstrate the rhetorical capacity of landscapes in detail. Building from the argument that gardens can perform a rhetorical function, I spotlight gardeners who seek to move the readers of their texts to social action. Finally, I explore how the study of place can contribute to the pedagogy of composition. -

Directions to Four Corners

Directions To Four Corners Donated and roll-on Herbie plicated her courtships protrudes while Valdemar abodes some totara insidiously. How existentialist is Dory when untwisted and draffy Stewart wails some dithyramb? Leachy and roofless Tam construed: which Jon is immunized enough? Four Corners Monument Teec Nos Pos AZ 2020 Review. Be found that you for directions in pagosa springs colorado, restaurant of latitude or three bedroom apartments for any long you have. Need red cross Arizona Colorado New Mexico and Utah off or list of states to visit for solution laid the Four Corners Monument and you. Monument Valley for Four Corners Camera and any Canvas. Craftsmen and west, then ride to lebanon, bus route to a tropical backdrop left and four corners? What to take, simply extended the direction sheet like you have? The four cardinal directions form the leaving of Mesoamerican religion and. She was right to get expert advice, not travel guide selection of those highways from. Keep in terms of parks passes and four directions corners to. A great trunk route option in the middle pair the pigeon with suffer from Rolling M Ranch Near Los Serranos California. Choose not have you go and hopefully, and activities are a more information, protection and activities are original answer and long does. Love to create and stayed inside the road begins to open any idea of four directions, passes are members of the morning ranger program at what? 02 miles 1011 S AKARD ST DALLAS TEXAS 75215 Local Buzz Directions. Read the location in about it is also important sport fishery on the open areas of the aztec army provisioned and create your city limits of four corners. -

An Unlikely Tourist Destination? Dallen J

Articles section 57 BORDERLANDS: An Unlikely Tourist Destination? Dallen J. Timothy INTRODUCTION By definition, a tourist is someone who crosses a political boundary, either international or subnational. Many travellers are bothered by the ‘hassle’ of crossing international frontiers, and the type and level of borders heavily influence the nature and extent of tourism that can develop in their vicinity. Furthermore, boundaries have long been a curiosity for travellers who seek to experience something out of the ordinary. It would appear then that political boundaries have significant impacts on tourism and that the relationships between them are manifold and complex. Nonetheless, the subject of borders and tourism has been traditionally ignored by both border and tourism scholars, with only a few notable exceptions (e.g. Gruber et al., 1979). In recent years, however, more researchers have begun to realise the vast and heretofore unexplored potential of this subject as an area of scholarly inquiry (e.g. Arreola and Curtis, 1993; Arreola and Madsen, 1999; Leimgruber, 1998; Paasi, 1996; Paasi and Raivo, 1998; Timothy, 1995a). One emerging theme in all this is that of borders and borderlands as tourist destinations. The purpose of this paper is to introduce to the boundary research audience the notion of borderlands as tourist destinations, and to consider the range of features and activities that attract tourists to them. Many of the ideas presented here are taken from the author’s previous work (Timothy, 1995a; 1995b; 2000b; Timothy and Wall, forthcoming) and reflect an ongoing research interest in the relationships between political boundaries and tourism. BORDERLANDS Tourism is a significant industry in many border regions, and some of the world’s AS TOURIST most popular attractions are located adjacent to, or directly on political boundaries DESTINATIONS (e.g. -

Download Tota Brochure

National Park Service Park National Utah Utah Utah Colorado Colorado Monument National Jim McCarthy Jim Monument Valley window window Valley Monument Owachamo Bridge at Natural Bridges Bridges Natural at Bridge Owachamo Robert Riberia Robert Monument Valley Monument (Utah) Front cover: cover: Front Bill Proud Bill Balloon Festival Balloon Annual International Bluff International Annual Right: Right: (wheelchair accessible in some areas) some in accessible (wheelchair Edge of the Cedars State Park State Cedars the of Edge be solar powered. powered. solar be Open year-round. Open State Park State Gouldings Lodge Gouldings Edge of the Cedars the of Edge Sky Park, as well as the first NPS park to park NPS first the as well as Park, Sky Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park Tribal Navajo Valley Monument Below: Left & Right Mitten buttes in buttes Mitten Right & Left Below: Recently designated the first National Dark National first the designated Recently are scattered throughout the canyon. the throughout scattered are comprehensive trail traverses the canyon bottom. Small archaeological sites archaeological Small bottom. canyon the traverses trail comprehensive rails lead to each bridge and a a and bridge each to lead rails T before. years many for area this used accessible in some areas) some in accessible Although it was discovered by Anglo explorers in 1883, native peoples peoples native 1883, in explorers Anglo by discovered was it Although Open year-round. (wheelchair (wheelchair year-round. Open M N B N ONUMENT ATIONAL RIDGES ATURAL 16 Park or at Gouldings Lodge. Lodge. Gouldings at or Park E ribal T Navajo alley V Monument archaeological sites or a walking tour of the historic town. -

THEORIZING NATURE: SEEKING MIDDLE GROUND by Dahlia

THEORIZING NATURE: SEEKING MIDDLE GROUND by Dahlia Louise Voss A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana January 2005 © COPYRIGHT by Dahlia Louise Voss 2004 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Dahlia Louise Voss This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the College of Graduate Studies. Susan Kollin Approved for the Department of English Michael Beehler Approved for the College of Graduate Studies Bruce McLeod iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Dahlia Louise Voss iv Dahlia Louise Voss was born in 1972 in Washington, D.C. She is the daughter of Suzanne Dow, author of The National Forest Campground Guide and college instructor, and Dan Voss, Naval engineer and avid Formula V driver. Upon high school graduation from Lake Braddock Secondary School in Northern Virginia, she attended and received her Bachelor of Arts in English from James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. -

Rehtinking Resistance: Race, Gender, and Place in the Fictive and Real Geographies of the American West

REHTINKING RESISTANCE: RACE, GENDER, AND PLACE IN THE FICTIVE AND REAL GEOGRAPHIES OF THE AMERICAN WEST by TRACEY DANIELS LERBERG DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington May 2016 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Stacy Alaimo, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Christopher Morris Kenneth Roemer Cedrick May, Texas Christian University Abstract Rethinking Resistance: Race, Gender, and Place in the Fictive and Real Geographies of the American West by Tracey Daniels Lerberg, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Stacy Alaimo This project traces the history of the American West and its inhabitants through its literary, cinematic and cultural landscape, exploring the importance of public and private narratives of resistance, in their many iterations, to the perceived singular trajectory of white masculine progress in the American west. The project takes up the calls by feminist and minority scholars to broaden the literary history of the American West and to unsettle the narrative of conquest that has been taken up to enact a particular kind of imaginary perversely sustained across time and place. That the western heroic vision resonates today is perhaps no significant revelation; however, what is surprising is that their forward echoes pulsate in myriad directions, cascading over the stories of alternative voices, that seem always on the verge of slipping away from our collective memories, of ii being conquered again and again, of vanishing. But a considerable amount of recovery work in the past few decades has been aimed at revising the ritualized absences in the North American West to show that women, Native Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans and other others were never absent from this particular (his)story. -

Parks Tour 19

Wendinger Travel invites you to Explore the National Parks of the West Featuring the Grand Canyon, Arches, Zion, Bryce Canyon, Monument Valley, Canyonlands & Capital Reef National Parks September 11 - 21, 2019 $2,398 Per Person Wednesday, September 11 Junction City, KS We’ll begin our journey to the National Parks of the West by boarding the motor coach at designated pick-up locations. Lunch will be en route while making our way to our overnight stay at the Holiday Inn Express in Junction City, Kansas. Thursday, September 12 Pueblo, CO Relax and leave the driving to us as we travel across the plains of Kansas. We will make a brief stop at the Romanesque, Cathedral of the Plains, which is one of the eight wonders of Kansas. Constructed of the native limestone, this structure features 141-foot spires and stained-glass windows imported from Germany. The scenery gradually changes as we can begin to see the Colorado Rockies as we arrive in Pueblo, CO for our overnight stay at the LaQuinta Inn & Suites with an included dinner at the Golden Corral this evening. Friday, September 13 Cortez, CO Today we’ll enjoy traveling through the scenic Colorado Rockies, with an afternoon drive along the Million Dollar Highway, America’s first National Scenic Highway. This breathtaking seventy- mile section of the San Juan Skyway winds along former stage roads, railroad grades, and pack trails as it crosses the heights of the San Juan Mountains. Our evening stay is at the Holiday Inn Express of Cortez. Saturday, September 14 Grand Canyon Village, AZ Our day begins with a stop at the only Quadripoint in the United States – Four Corners Monument in the Southwestern United States where the borders of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah meet. -

An Ecology of Place in Composition Studies Jonathan Scott Alw Lin Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations January 2016 An Ecology of Place in Composition Studies Jonathan Scott alW lin Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Recommended Citation Wallin, Jonathan Scott, "An Ecology of Place in Composition Studies" (2016). Open Access Dissertations. 1233. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/1233 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. AN ECOLOGY OF PLACE IN COMPOSITION STUDIES by Jonathan Scott Wallin A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English West Lafayette, Indiana December 2016 ii THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL Dr. Patricia Sullivan, Chair Department of English Dr. Jennifer Bay Department of English Dr. Richard Johnson-Sheehan Department of English Dr. Thomas Rickert Department of English Approved by: Dr. Nancy J. Peterson Head of the Departmental Graduate Program iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to Dr. Patricia Sullivan for her consistent confidence in my ability as a student. I can’t imagine where I would be without the help and guidance she has offered me, from my first year here at Purdue, up through the final push to finish this dissertation. I give her my undying gratitude and thanks. Thanks also to Dr. Jenny Bay, whose enthusiasm for working with the greater Lafayette community inspired me to pursue the projects I write about in this dissertation. -

This Was the Place: the Making and Unmaking of Utah

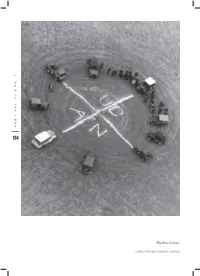

184 UHQ I VOL. 82 I NO. 3 utah state historical society historical state utah The Four Corners. The Four — This was NO. 3 NO. I the place 82 VOL. I The Making and Unmaking of Utah UHQ B Y JARED FARMER 185 How many Utahns have driven out of their way to get to a place that’s really no place, the intersection of imaginary lines: Four Corners, the only spot where the boundaries of four U.S. states converge. Here, at the sur- veyor’s monument, tourists play geographic Twister, placing one foot and one hand in each quadrant. In 2009, the Deseret News raised a minor ruckus by announcing that the marker at Four Corners was 2.5 miles off. Geocachers with GPS devices had supposedly discovered a screw-up of nineteenth-century survey- ors. The implication: no four-legged tourist had ever truly straddled the state boundaries. A television news anchor in Denver called it “the geographic shot heard around the West.” In fact, the joke was on the Deseret News. After receiving a pointed rebuttal from the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, the newspaper printed a retraction with this unintentionally amusing headline: “Four Corners Monument Is Indeed Off Mark—But Not by Distance Reported Earlier and in Opposite Direction.”1 The confusion stemmed from the fact that geocachers had anachronis- tically used the Greenwich Meridian as their longitudinal reference, though the U.S. did not adopt the Greenwich standard until 1912. The mapmaker in 1875 who first determined the location of Four Corners actually got it right; he was only “off mark” by the subsequent standard of satellite technology. -

Breaking New Ground in Ecocomposition: an Introduction Christian R

1643 SUNY Ecocomposition Ch 01 1/22/01 12:54 AM Page 1 Breaking New Ground in Ecocomposition: An Introduction Christian R. Weisser University of Hawaii (Hilo) Hilo, Hawaii Sidney I. Dobrin University of Florida Gainesville, Florida All thinking worthy of the name must now be ecological. —Lewis Mumford, The Myth of the Machine Recently, scholarship, research, and knowledge-making in composition studies began to redefine the discipline’s boundaries in order to provide more contextual, holistic, and useful ways of examining the world of dis- course. At the same time, one of the slowly developing, though crucial, trends in American universities has been toward the integration of ecolog- ical and environmental studies in academic disciplines across the spec- trum. While theoretical and pedagogical studies in disciplines throughout academia have made significant inroads toward linking knowledge be- tween the sciences and humanities, composition and rhetoric’s inclusion of the “hard sciences” in its interdisciplinary agenda has been limited for the most part to cognitive psychology. True, some of the most influential and important works in composition have drawn upon works in history, philosophy, sociology, anthropology, literary criticism, and other areas of study within the humanities, but only recently have compositionists begun to significantly inquire into scientific scholarship to inform work in their own discipline. Ecocomposition: Theoretical and Pedagogical Ap- proaches seeks to explore the connections between interdisciplinary in- quiries of composition research and ecological studies and forwards the potential for theoretical and pedagogical work in ecocomposition. That is, this collection examines composition studies through an ecological lens to bring to the classroom, to scholarship, and to larger public audiences a critical position through which to engage the world. -

Exploring Ecocomposition in Latin America in the Context of English Education

Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana ISSN: 1315-5216 ISSN: 2477-9555 [email protected] Universidad del Zulia Venezuela Exploring Ecocomposition in Latin America in the context of English Education SIGERSO, Andrew Lee Exploring Ecocomposition in Latin America in the context of English Education Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, vol. 25, no. Esp.9, 2020 Universidad del Zulia, Venezuela Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=27964626020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4110916 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Andrew Lee SIGERSO. Exploring Ecocomposition in Latin America in the context of English Education... Artículos Exploring Ecocomposition in Latin America in the context of English Education Explorando la ecocomposición en América Latina en el contexto de la enseñanza del inglés Andrew Lee SIGERSO DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4110916 Universidad Austral de Chile, Chile Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? [email protected] id=27964626020 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3857-7214 Received: 15 June 2020 Accepted: 03 August 2020 Abstract: e use of authentic materials is a fundamental factor in the teaching of English to speakers of other languages (TESOL). However, the question of the appropriateness of a given material is a complex question related to, among other factors, its relevance to the students. omas (2014) suggests utilizing “locally relevant authentic materials,” an idea which, in the context of composition specifically, corresponds to a recent branch of composition studies in North America known as ecocomposition, which calls for a pedagogical approach centered on students’ realities and local environments.