Difluoromethane (R-32) from China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1,1,1,2-Tetrafluoroethane

This report contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, or the World Health Organization. Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 11 1,1,1,2-Tetrafluoroethane First draft prepared by Mrs P. Barker and Mr R. Cary, Health and Safety Executive, Liverpool, United Kingdom, and Dr S. Dobson, Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, Huntingdon, United Kingdom Please not that the layout and pagination of this pdf file are not identical to the printed CICAD Published under the joint sponsorship of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, and the World Health Organization, and produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals. World Health Organization Geneva, 1998 The International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS), established in 1980, is a joint venture of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and the World Health Organization (WHO). The overall objectives of the IPCS are to establish the scientific basis for assessment of the risk to human health and the environment from exposure to chemicals, through international peer review processes, as a prerequisite for the promotion of chemical safety, and to provide technical assistance in strengthening national capacities for the sound management of chemicals. The Inter-Organization -

SAFETY DATA SHEET Difluoromethane (R32) SECTION 1

SAFETY DATA SHEET Difluoromethane (R32) Issue Date: 16.01.2013 Version: 1.1 SDS No.: 000010021734 Last revised date: 26.11.2018 1/14 SECTION 1: Identification of the substance/mixture and of the company/undertaking 1.1 Product identifier Product name: Difluoromethane (R32) Other Name: HFC-32 Additional identification Chemical name: Difluoromethane Chemical formula: CH2F2 INDEX No. - CAS-No. 75-10-5 EC No. 200-839-4 REACH Registration No. 01-2119471312-47 1.2 Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Identified uses: Industrial and professional. Perform risk assessment prior to use. Refrigerant. Use as an Intermediate (transported, on-site isolated). Use for electronic component manufacture. Using gas alone or in mixtures for the calibration of analysis equipment. Formulation of mixtures with gas in pressure receptacles. Uses advised against Consumer use. 1.3 Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Supplier Linde Gas GmbH Telephone: +43 50 4273 Carl-von-Linde-Platz 1 A-4651 Stadl-Paura E-mail: [email protected] 1.4 Emergency telephone number: Emergency number Linde: + 43 50 4273 (during business hours), Poisoning Information Center: +43 1 406 43 43 SECTION 2: Hazards identification 2.1 Classification of the substance or mixture Classification according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 as amended. Physical Hazards Flammable gas Category 1 H220: Extremely flammable gas. Gases under pressure Liquefied gas H280: Contains gas under pressure; may explode if heated. SDS_AT - 000010021734 SAFETY DATA SHEET Difluoromethane (R32) Issue Date: 16.01.2013 Version: 1.1 SDS No.: 000010021734 Last revised date: 26.11.2018 2/14 2.2 Label Elements Signal Words: Danger Hazard Statement(s): H220: Extremely flammable gas. -

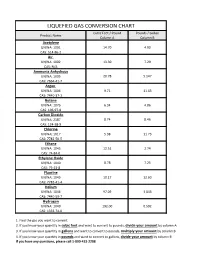

Liquefied Gas Conversion Chart

LIQUEFIED GAS CONVERSION CHART Cubic Feet / Pound Pounds / Gallon Product Name Column A Column B Acetylene UN/NA: 1001 14.70 4.90 CAS: 514-86-2 Air UN/NA: 1002 13.30 7.29 CAS: N/A Ammonia Anhydrous UN/NA: 1005 20.78 5.147 CAS: 7664-41-7 Argon UN/NA: 1006 9.71 11.63 CAS: 7440-37-1 Butane UN/NA: 1075 6.34 4.86 CAS: 106-97-8 Carbon Dioxide UN/NA: 2187 8.74 8.46 CAS: 124-38-9 Chlorine UN/NA: 1017 5.38 11.73 CAS: 7782-50-5 Ethane UN/NA: 1045 12.51 2.74 CAS: 74-84-0 Ethylene Oxide UN/NA: 1040 8.78 7.25 CAS: 75-21-8 Fluorine UN/NA: 1045 10.17 12.60 CAS: 7782-41-4 Helium UN/NA: 1046 97.09 1.043 CAS: 7440-59-7 Hydrogen UN/NA: 1049 192.00 0.592 CAS: 1333-74-0 1. Find the gas you want to convert. 2. If you know your quantity in cubic feet and want to convert to pounds, divide your amount by column A 3. If you know your quantity in gallons and want to convert to pounds, multiply your amount by column B 4. If you know your quantity in pounds and want to convert to gallons, divide your amount by column B If you have any questions, please call 1-800-433-2288 LIQUEFIED GAS CONVERSION CHART Cubic Feet / Pound Pounds / Gallon Product Name Column A Column B Hydrogen Chloride UN/NA: 1050 10.60 8.35 CAS: 7647-01-0 Krypton UN/NA: 1056 4.60 20.15 CAS: 7439-90-9 Methane UN/NA: 1971 23.61 3.55 CAS: 74-82-8 Methyl Bromide UN/NA: 1062 4.03 5.37 CAS: 74-83-9 Neon UN/NA: 1065 19.18 10.07 CAS: 7440-01-9 Mapp Gas UN/NA: 1060 9.20 4.80 CAS: N/A Nitrogen UN/NA: 1066 13.89 6.75 CAS: 7727-37-9 Nitrous Oxide UN/NA: 1070 8.73 6.45 CAS: 10024-97-2 Oxygen UN/NA: 1072 12.05 9.52 CAS: 7782-44-7 Propane UN/NA: 1075 8.45 4.22 CAS: 74-98-6 Sulfur Dioxide UN/NA: 1079 5.94 12.0 CAS: 7446-09-5 Xenon UN/NA: 2036 2.93 25.51 CAS: 7440-63-3 1. -

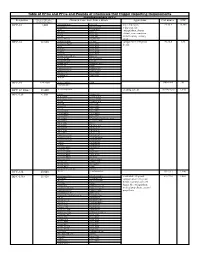

Gas Conversion Factor for 300 Series

300GasTable Rec # Gas Symbol GCF Density (g/L) Density (g/L) 25° C / 1 atm 0° C / 1 atm 1 Acetic Acid C2H4F2 0.4155 2.7 2.947 2 Acetic Anhydride C4H6O3 0.258 4.173 4.555 3 Acetone C3H6O 0.3556 2.374 2.591 4 Acetonitryl C2H3N 0.5178 1.678 1.832 5 Acetylene C2H2 0.6255 1.064 1.162 6 Air Air 1.0015 1.185 1.293 7 Allene C3H4 0.4514 1.638 1.787 8 Ammonia NH3 0.7807 0.696 0.76 9 Argon Ar 1.4047 1.633 1.782 10 Arsine AsH3 0.7592 3.186 3.478 11 Benzene C6H6 0.3057 3.193 3.485 12 Boron Trichloride BCl3 0.4421 4.789 5.228 13 Boron Triflouride BF3 0.5431 2.772 3.025 14 Bromine Br2 0.8007 6.532 7.13 15 Bromochlorodifluoromethane CBrClF2 0.3684 6.759 7.378 16 Bromodifluoromethane CHBrF2 0.4644 5.351 5.841 17 Bromotrifluormethane CBrF3 0.3943 6.087 6.644 18 Butane C4H10 0.2622 2.376 2.593 19 Butanol C4H10O 0.2406 3.03 3.307 20 Butene C4H8 0.3056 2.293 2.503 21 Carbon Dioxide CO2 0.7526 1.799 1.964 22 Carbon Disulfide CS2 0.616 3.112 3.397 23 Carbon Monoxide CO 1.0012 1.145 1.25 24 Carbon Tetrachloride CCl4 0.3333 6.287 6.863 25 Carbonyl Sulfide COS 0.668 2.456 2.68 26 Chlorine Cl2 0.8451 2.898 3.163 27 Chlorine Trifluoride ClF3 0.4496 3.779 4.125 28 Chlorobenzene C6H5Cl 0.2614 4.601 5.022 29 Chlorodifluoroethane C2H3ClF2 0.3216 4.108 4.484 30 Chloroform CHCl3 0.4192 4.879 5.326 31 Chloropentafluoroethane C2ClF5 0.2437 6.314 6.892 32 Chloropropane C3H7Cl 0.308 3.21 3.504 33 Cisbutene C4H8 0.3004 2.293 2.503 34 Cyanogen C2N2 0.4924 2.127 2.322 35 Cyanogen Chloride ClCN 0.6486 2.513 2.743 36 Cyclobutane C4H8 0.3562 2.293 2.503 37 Cyclopropane C3H6 0.4562 -

Table of Hfcs and Pfcs and Pounds of Chemicals That Trigger

Table of HFCs and PFCs and Pounds of Chemicals that Trigger Reporting Requirements Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) Designation Pounds of Substance = Chemical Name, Trade Names, Blends Applications CAS number GWP 10,000 metric tons Ce HFC-23 1,480 trifluoromethane Suva 95 low temperature 75-46-7 14,800 fluoroform Genetron 503 refrigerant, fire R-23 Genetron 23 extinguishant, plasma Freon 23 Klea 23 FE-13 Klea 508 etchant, semi-conductor FE-36 Klea 5R3 manufacturing cleaning Forane FX 220 NARM 503 agent HFC-32 32,660 difluoromethane R-407C component in refrigerant 75-10-5 675 methylene fluoride Klea 407A blends R-32 Klea 407B R-410A Klea 407C R-407C Klea 407D Freon 32 Klea 410A Forane 410A (AZ-20) Klea 32 Forane FX 40 Genetron 407C Forane FX 220 AZ-20 Forane 407C EcoloAce 407c Forane 32 HX4 Asahiklin SA-39 Solkane 407C Asahiklin SA-45 Solkane 410 Meforex 98 Suva 9000 Meforex 32 Suva 9100 R-410A HFC-41 227,280 methyl fluoride R-41 593-53-3 97 fluoromethane HFC-43-10mee 13,440 decafluoropentane cleaning solvent 138495-42-8 1,640 HFC-125 6,300 ethane Forane 507 pentafluoro Forane FX10 pentafluoroethane Forane FX40 R-125 Forane FX70 FC-125 Suva 125 Freon 125 Suva 9000 FE-25 Suva 9100 Arcton 402A Suva HP62 Arcton 402B Suva HP80 Arcton 408A Suva HP81 Klea 404A Cooltop R-134a Replacement Klea 407A EcoloAce 404a Klea 407B Di 44 Klea 407C Meforex 125 Klea 407D Meforex 55 Klea 410A Meforex 57 Klea 507A Meforex 98 Asahiklin SA-28 ISCEON 29 Asahiklin SA-39 ISCEON 404A Asahiklin SA-45 ISCEON 507 AZ-20 ISCEON 59 AZ-50 ISCEON 79 Genetron 404A ISCEON 89 Genetron -

R32 Common Questions

Frequently Asked Questions 1. How will the new F-gas regulation affect the choice of refrigerant for heat pump air conditioners? Heat pump air conditioning systems are impacted by the new F-gas regulation, the gradual phase down of HFC’s quantities on the market will push the industry to use lower GWP refrigerants. Since 2017 the price of HFC’s has started to rise significantly, especially for those gases with high Global Warming Potential (GWP). Note: In the new F-gas regulation, the use of HFC’s with GWP greater than 750 will be prohibited from 2025 for mono split-system room air conditioners containing less than 3 kg of refrigerant. 2. What is Toshiba’s refrigerant of choice as a replacement for R-410A heat pump air conditioners? R-410A alternatives must provide an acceptable compromise in terms of GWP, human safety, energy efficiency, and system cost. After several years of research and evaluation, Toshiba along with other air conditioner manufacturers are switching from R-410A to R-32 (Difluoromethane HFC32) refrigerant which has a lower Global Warming Potential (GWP), is better for the environment and delivers greater energy efficiency. However this gas is mildly flammable (A2L safety class) and does require some redesign change. These changes will be seen in our new range of R32 residential and light commercial heat pump air conditioning systems. The benefits of HFC R-32 are:- - Zero Ozone Depletion - 1/3 GWP of HFC 410A (GWP675 v GWP2088) - Superior energy efficiency - High refrigeration capacity and thermal conductivity - Low -

Freon™ 407C and 407A Properties, Uses, Storage, and Handling

Freon™ 407C and 407A Refrigerants (R-407C and R-407A) Properties, Uses, Storage, and Handling Freon™ Refrigerants Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................4 Air Monitors and Leak Detection ...................................... 16 Freon™ 407C and Freon™ 407A Refrigerant Types of Detectors .................................................................................16 Descriptions ................................................................................................... 4 Nonselective Detectors .................................................................16 Uses ......................................................................................4 Halogen-Selective Detectors ....................................................16 Physical Properties ...............................................................4 Compound-Specific Detectors .................................................16 Fluorescent Additives .....................................................................16 Chemical/Thermal Stability .............................................. 10 Stability with Metals .............................................................................10 Storage and Handling ........................................................ 17 Thermal Decomposition......................................................................11 Shipping Containers in the United States ..............................17 Compatibility Concerns If HCFC-22 and Freon™ Bulk Storage -

Freon™ 410A (R-410A) Refrigerant

SAFETY DATA SHEET Freon™ 410A (R-410A) Refrigerant Version Revision Date: SDS Number: Date of last issue: 04/20/2021 10.7 08/23/2021 1336443-00047 Date of first issue: 02/27/2017 SECTION 1. IDENTIFICATION Product name : Freon™ 410A (R-410A) Refrigerant SDS-Identcode : 130000050990 Manufacturer or supplier's details Company name of supplier : The Chemours Company FC, LLC Address : 1007 Market Street Wilmington, DE 19801 United States of America (USA) Telephone : 1-844-773-CHEM (outside the U.S. 1-302-773-1000) Emergency telephone : Medical emergency: 1-866-595-1473 (outside the U.S. 1-302- 773-2000) ; Transport emergency: +1-800-424-9300 (outside the U.S. +1-703-527-3887) Recommended use of the chemical and restrictions on use Recommended use : Refrigerant Restrictions on use : For professional users only. SECTION 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION GHS classification in accordance with the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200) Gases under pressure : Liquefied gas Simple Asphyxiant GHS label elements Hazard pictograms : Signal Word : Warning Hazard Statements : H280 Contains gas under pressure; may explode if heated. May displace oxygen and cause rapid suffocation. Precautionary Statements : Storage: P410 + P403 Protect from sunlight. Store in a well-ventilated place. 1 / 16 SAFETY DATA SHEET Freon™ 410A (R-410A) Refrigerant Version Revision Date: SDS Number: Date of last issue: 04/20/2021 10.7 08/23/2021 1336443-00047 Date of first issue: 02/27/2017 Other hazards Vapors are heavier than air and can cause suffocation by reducing oxygen available for breathing. Misuse or intentional inhalation abuse may cause death without warning symptoms, due to cardi- ac effects. -

Next Generation Refrigerants: Standards and Climate Policy Implications of Engineering Constraints

Next Generation Refrigerants: Standards and Climate Policy Implications of Engineering Constraints Hung Pham, Emerson Climate Technologies Harvey Sachs, American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy ABSTRACT There is no single perfect refrigerant for diverse air conditioning, refrigeration, and industrial applications. The predominant halocarbons (CFCs, HCFCs, and HFCs) combine excellent efficiency and safety with acceptable costs. However, they contribute to ozone depletion potential (ODP) and/or global warming potential (GWP). The Montreal Protocol has eliminated ODP by requiring replacement of CFCs and HCFCs with HFCs such as R-410A, R- 407C, and R134a. The next focus is a worldwide technical and policy search for next-generation refrigerants with low global warming potential (LGWP). Potential options include “natural” refrigerants such as carbon dioxide (CO2), hydrocarbons (HC), and ammonia (NH3) as well as HFOs and HFO/HFC blends. All involve significant trade-offs among GWP, energy efficiency, safety, and cost. Environmental policy must consider the indirect effects of increased CO2 emissions for less efficient refrigerants, not just the direct global warming (GWP) of the refrigerant. We must insist on using metrics such as Total Equivalent Warming Impact (TEWI) that balance refrigerant direct GWP, charge level, leakage emissions, and efficiency of the refrigerant in actual systems. This allows the best possible comparison of refrigerants for each application. In the right policy environment, we can achieve reduced environmental impact and increase efficiency. This will probably require increased differentiation of application-specific refrigerant choices that are associated with somewhat higher first costs but very attractive life cycle costs with acceptable safety and environmental impacts. Background One of the major transformations of the 20th Century is the widespread use of modern, effective, and safe space air conditioning, particularly for the hot climate in the South and Southwest of the U.S. -

Classification of Refrigerants

INSTITUT INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE DU FROID OF REFRIGERATION Organisation intergouvernement ale Intergovernmental organization pour le développement du froid for the development of refrigeration 177, boulevard Malesherbes, 75017 PARIS, France - Tél. 33-(0)1 42 27 32 35 - Fax 33-(0)1 47 63 17 98 - E-mail : [email protected] - Web : www.iifiir.org Classification of refrigerants This text is based on the American standard ANSI/ASHRAE 34 published in 2001 and entitled “Designation and Safety Classification of Refrigerants”. This classification makes it possible to designate all refrigerants used in a clear and internationally recognized manner by classifying them according to their chemical composition. 1 Numbering of Refrigerants An identifying number shall be assigned to each refrigerant. It consists of a prefix made up of letters and a suffix made up of digits. 1.1 Prefixes The prefix is composed of the letter R (for refrigerant). Examples: R22, R134a, R600a, R717 Sometimes, the letter C is used in the prefix to denote carbon, preceded by B, C or F (or a combination of these letters in the same order) to indicate the presence of bromine, chlorine or fluorine. Compounds containing hydrogen must be preceded by the letter H. Examples: HCFC22, HFC134a These prefixes must only be used in non-technical publications. Note: the name of the brand or of the manufacturer is also used sometimes; these names must not be used in official documents (identification labels, etc.). 1.2 Suffixes • Hydrocarbons and derivatives The first digit on the right (units) is the number of fluorine (F) atoms. The second digit on the right (tens) is one more than the number of hydrogen (H) atoms. -

Global Warming Potentials

Appendix A: Global Warming Potentials When reporting emissions of non-CO2 gases, the mass estimates of these gases must also be reflected in the public report on a CO2e basis. Converting emissions of non-CO2 gases to units of CO2e allows GHGs to be compared on a common basis, i.e., the ability of each GHG to trap heat in the atmosphere. GWP factors represent the ratio of the heat-trapping ability of each GHG relative to that of CO2. TCR relies on GWP defaults published by the IPCC. As part of its activities, the IPCC revisits and updates these defaults in periodic Assessment Reports. When reporting emissions to TCR, members may use GRPs from the Assessment Report that is most relevant to their operations providing the following conditions are met: 1. All GRPs must be 100 year values; 2. Where possible within an inventory, all GWPs must come from a single Assessment Report. If GWPs for a particular gas are not provided in the chosen Assessment Report, members must select the more recent GRP for that has; and, 3. The source of all GRP values must be disclosed publicly. Although not required, it is considered best practice to use GWP values from the most recent Assessment Report. However, when a base year has been set, it is best practice to use the same GWP values for the current inventory and the base year inventory. Organizations that select a GWP different that is not from the most recent Assessment Report must justify their selection if they seek to conform with ISO 14064-1: 2018. -

List of Refrigerants

Refrigerant Table: Explanation and Glossary of Terms A reference list of refrigerants which is intended to provide an indication of the basic characteristics, properties and applications for a variety of refrigerants along with some replacement options was prepared upon the recommendation of HRAI’s Task Team on the Future of Refrigerants. This list is intended to assist contractors as a convenient reference when selecting suitable replacement/substitute refrigerants for those refrigerants (CFC and any HCFC) which are being phased out. While refrigerant manufacturers may indicate some products are suitable for retrofit applications, the contractor will need to consider the application in order to determine the extent of system modifications that may be required to accommodate the replacement refrigerant. Currently, one must verify with the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) to determine compatibility of alternative refrigerants with the equipment, or have a Professional Engineer sign off. Unless otherwise specified, few if any replacement refrigerants in the table are certified as a direct drop‐in replacement, in fact most are certified for new equipment only and are not suitable for retrofit applications. Contractors would still have to determine which products are suitable for their particular application, if equipment replacement or retrofit options exist, which system modifications may be required and choose accordingly. Depending on the age of the existing equipment and the extent of system modifications required to accommodate an alternate refrigerant, it may prove to be more cost effective in the long run to replace equipment outright. As the phase down of certain refrigerants causes them to become scarcer, decreasing availability and increasing cost can be expected to result in the change‐out of entire systems to more energy efficient equipment and environmentally friendly refrigerants.