THE DATIVE ALTERNATION in ENGLISH with Four Different

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Dative Alternation and Evidence for a Thematic Strategy in Adult SLA

UCLA Issues in Applied Linguistics Title English Dative Alternation and Evidence for a Thematic Strategy in Adult SLA Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/64d102q5 Journal Issues in Applied Linguistics, 5(1) ISSN 1050-4273 Author Davies, William D Publication Date 1994-06-30 DOI 10.5070/L451005171 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California English Dative Alternation and Evidence for a Thematic Strategy in Adult SLA William D. Davies University of Iowa INTRODUCTION A body of recent work in second language acquisition is concerned with applying constructs from Chomsky's conception of Universal Grammar in both constructing an overall theory of SLA and explaining various phenomena in L2 learners (e.g., Flynn, 1984, 1987; Hilles, 1986; Phinney, 1987; White, 1985a, 1985b; papers in Flynn and O'Neil, 1988). A key linguistic construct that has received relatively little attention in SLA research is thematic roles—notions such as AGENT, THEME, GOAL, LOCATION, SOURCE, and others that are believed to contribute to semantic encoding and decoding. Although thematic roles (alternatively, thematic relations, semantic roles, case roles, 9-roles) have long been part of modem linguistic theory (cf. Gruber, 1965; Fillmore, 1968; Jackendoff, 1972), they have enjoyed increased popularity in the recent linguistic literature owing in part to their central role in Chomsky's (1981) government and binding (GB) theory, as embodied in the G-Criterion.^ Various formulations of the 9-Criterion have been proposed, but the simple formulation in (1) will suffice here. (1) e-Criterion (Chomsky 1981, p. 36): Each argument bears one and only one H-role, and each H-role is assigned to one and only one argument. -

PUMICE: a Multi-Modal Agent That Learns Concepts and Conditionals

PUMICE: A Multi-Modal Agent that Learns Concepts and Conditionals from Natural Language and Demonstrations Toby Jia-Jun Li1, Marissa Radensky2, Justin Jia1, Kirielle Singarajah1, Tom M. Mitchell1, Brad A. Myers1 1Carnegie Mellon University, 2Amherst College {tobyli, tom.mitchell, bam}@cs.cmu.edu, {justinj1, ksingara}@andrew.cmu.edu, [email protected] Figure 1. Example structure of how PUMICE learns the concepts and procedures in the command “If it’s hot, order a cup of Iced Cappuccino.” The numbers indicate the order of utterances. The screenshot on the right shows the conversational interface of PUMICE. In this interactive parsing process, the agent learns how to query the current temperature, how to order any kind of drink from Starbucks, and the generalized concept of “hot” as “a temperature (of something) is greater than another temperature”. ABSTRACT CCS Concepts Natural language programming is a promising approach to •Human-centered computing ! Natural language inter enable end users to instruct new tasks for intelligent agents. faces; However, our formative study found that end users would of ten use unclear, ambiguous or vague concepts when naturally Author Keywords instructing tasks in natural language, especially when spec Programming by Demonstration; Natural Language Pro ifying conditionals. Existing systems have limited support gramming; End User Development; Multi-modal Interaction. for letting the user teach agents new concepts or explaining unclear concepts. In this paper, we describe a new multi- INTRODUCTION modal domain-independent approach that combines natural The goal of end user development (EUD) is to empower language programming and programming-by-demonstration users with little or no programming expertise to program [43]. -

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

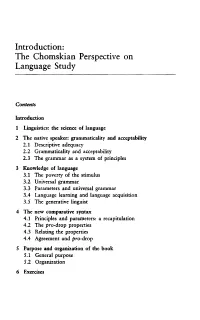

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

Definiteness and Determinacy

Linguistics and Philosophy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Definiteness and Determinacy Elizabeth Coppock · David Beaver the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract This paper distinguishes between definiteness and determinacy. Defi- niteness is seen as a morphological category which, in English, marks a (weak) uniqueness presupposition, while determinacy consists in denoting an individual. Definite descriptions are argued to be fundamentally predicative, presupposing uniqueness but not existence, and to acquire existential import through general type-shifting operations that apply not only to definites, but also indefinites and possessives. Through these shifts, argumental definite descriptions may become either determinate (and thus denote an individual) or indeterminate (functioning as an existential quantifier). The latter option is observed in examples like `Anna didn't give the only invited talk at the conference', which, on its indeterminate reading, implies that there is nothing in the extension of `only invited talk at the conference'. The paper also offers a resolution of the issue of whether posses- sives are inherently indefinite or definite, suggesting that, like indefinites, they do not mark definiteness lexically, but like definites, they typically yield determinate readings due to a general preference for the shifting operation that produces them. Keywords definiteness · descriptions · possessives · predicates · type-shifting We thank Dag Haug, Reinhard Muskens, Luca Crniˇc,Cleo Condoravdi, Lucas -

Dative Shift) • Interactions Among Lexical Rules 2

Grammar Development with LFG and XLE Miriam Butt University of Konstanz Last Time • LFG and XLE basics • C-structure and f-structure • Functional annotation • Unification/Consistency, Completenes and Coherence • Templates • XLE Walkthrough This Time: Lesson 3 1. Lexical Rules • Passive • English Dative Alternation (Dative Shift) • Interactions among Lexical Rules 2. Different types of functional equations/constraints Lexical rules (vs. Transformations) ! A feature that LFG is very well known for is the Lexical Rule. ! At the time LFG was invented, generalizations between certain types of sentences were thought of in terms of syntactic transformations. ! A famous example involved the passive. ! Linguistic Observation: active clauses are related to passive clauses via a generalizable rule. » Active: The tiger chased the cat. » Passive: The cat was chased by the tiger. Transformations ! For example, within Transformational Grammar the rule for the English passive looked something like this: NP1 V NP2 → NP2 AUX V by NP1 ! In our example: NP1 = the tiger NP2 = the cat V = chased Aux = was ! Over time, however, it was realized that this was not the best way to express what happens with passives across languages. Lexical rules ! Work by David Perlmutter and Paul Postal showed that the relationship between active and passive was best understood in terms of grammatical relations. ! In LFG terms, this was formulated in terms of a Lexical Rule: – OBJ → SUBJ – SUBJ → Adjunct or OBL-AG (OBL agent) ! Verbs which allow for the passive encode this rule as part of their lexical entry. Lexical rules ! Not all verbs allow for passivization. ! Passives are generally formed with agentive (di)transitive verbs. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject-Sharing and Index-Sharing

Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject-Sharing and Index-Sharing Juwon Lee The University of Texas at Austin Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar University at Buffalo Stefan Muller¨ (Editor) 2014 CSLI Publications pages 135–155 http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/HPSG/2014 Lee, Juwon. 2014. Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject- Sharing and Index-Sharing. In Muller,¨ Stefan (Ed.), Proceedings of the 21st In- ternational Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, University at Buffalo, 135–155. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Abstract In this paper I present an account for the lexical passive Serial Verb Constructions (SVCs) in Korean. Regarding the issue of how the arguments of an SVC are realized, I propose two hypotheses: i) Korean SVCs are broadly classified into two types, subject-sharing SVCs where the subject is structure-shared by the verbs and index- sharing SVCs where only indices of semantic arguments are structure-shared by the verbs, and ii) a semantic argument sharing is a general requirement of SVCs in Korean. I also argue that an argument composition analysis can accommodate such the new data as the lexical passive SVCs in a simple manner compared to other alternative derivational analyses. 1. Introduction* Serial verb construction (SVC) is a structure consisting of more than two component verbs but denotes what is conceptualized as a single event, and it is an important part of the study of complex predicates. A central issue of SVC is how the arguments of the component verbs of an SVC are realized in a sentence. -

Syntax-Semantics Interface

: Syntax-Semantics Interface http://cognet.mit.edu/library/erefs/mitecs/chierchia.html Subscriber : California Digital Library » LOG IN Home Library What's New Departments For Librarians space GO REGISTER Advanced Search The CogNet Library : References Collection : Table of Contents : Syntax-Semantics Interface «« Previous Next »» A commonplace observation about language is that it consists of the systematic association of sound patterns with meaning. SYNTAX studies the structure of well-formed phrases (spelled out as sound sequences); SEMANTICS deals with the way syntactic structures are interpreted. However, how to exactly slice the pie between these two disciplines and how to map one into the other is the subject of controversy. In fact, understanding how syntax and semantics interact (i.e., their interface) constitutes one of the most interesting and central questions in linguistics. Traditionally, phenomena like word order, case marking, agreement, and the like are viewed as part of syntax, whereas things like the meaningfulness of a well-formed string are seen as part of semantics. Thus, for example, "I loves Lee" is ungrammatical because of lack of agreement between the subject and the verb, a phenomenon that pertains to syntax, whereas Chomky's famous "colorless green ideas sleep furiously" is held to be syntactically well-formed but semantically deviant. In fact, there are two aspects of the picture just sketched that one ought to keep apart. The first pertains to data, the second to theoretical explanation. We may be able on pretheoretical grounds to classify some linguistic data (i.e., some native speakers' intuitions) as "syntactic" and others as "semantic." But we cannot determine a priori whether a certain phenomenon is best explained in syntactic or semantics terms. -

Proceedings of the IWCS 2013 Workshop on Annotation of Modal

Challenges in modality annotation in a Brazilian Portuguese Spontaneous Speech Corpus Luciana Beatriz Avila SecondHeliana Author Mello Second Author PosLin-UFMG/UFV/Capes AffiliationUFMG/FGV/CNPq / Address line 1 Affiliation / Address line 1 Av Antonio Carlos 6627 AffiliationAv Antonio / Address Carlos 6627line 2 Affiliation / Address line 2 Belo Horizonte, MG 31270-901 Brazil Belo Horizonte,Affiliation MG/ Address 31270 line-901 3 Brazil Affiliation / Address line 3 [email protected] heliana.melloemail@[email protected] email@domain category stands for, as well as identifying linguistic Abstract elements that carry it, is of utmost relevance. Our goal in annotating modality in a This short paper introduces the first notes about a modality annotation system that is under spontaneous speech Brazilian Portuguese Corpus is development for a spontaneous speech to provide a reliable starting point for researchers Brazilian Portuguese corpus (C-ORAL- that might be interested in developing BRASIL). We indicate our methodological methodologies associated to NLP that ensue the decisions, the points which seem to be well extraction of oral discourse reliability, certainty resolved and two issues for further discussion and factuality markers, or carrying sentiment and investigation. analysis, modeling modality and similar objectives. 3 Defining modality 1 Credits In this paper we study modality in a spontaneous The authors are thankful to CNPq, FAPEMIG and speech corpus, the C-ORAL-BRASIL, which will CAPES (Proc. nº BEX 9537/12-0) for research be presented in 4 below. As for spontaneous funding support. speech, we follow Cresti and Scarano (1998:5) in characterizing it as “the fulfillment of linguistic 2 Introduction acts, not programmed and not programmable, Modality annotation is inexistent for both written because they emerge during the unfolding of an and spoken Brazilian Portuguese corpora, thus the interaction, always new and unpredictable, novelty of this project.