Canadian Literary Breakfasts1 Alexia Moyer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master List - Lectures Available from Culinary Historians

Master List - Lectures available from Culinary Historians The Culinary Historians of Southern California offer lectures on food and cultures from ancient to contemporary. Lectures that are well suited for young audiences are prefaced by a “Y” in parentheses, illustrated lectures with an “I”. Most lectures can be combined with a tasting of foods relevant to the topic. * * * Feride Buyuran is a chef and historian, as well as the author of the award-winning "Pomegranates & Saffron: A Culinary Journey to Azerbaijan." A Culinary Journey to Azerbaijan - The cooking of the largest country in the Caucasus region is influenced by Middle Eastern and Eastern European cuisines. This lecture explores the food of Azerbaijan within its historical, social, and cultural context. Feride Buyuran will highlight the importance of the Silk Road in the formation of the traditional cuisine and the dramatic impact of the Soviet era on the food scene in the country. (I) * * * Jim Chevallier began his food history career with a paper on the shift in breakfast in eighteenth century France. As a bread historian, he has contributed to the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, and his work on the baguette and the croissant has been cited in both books and periodicals. His most recent book is "A History of the Food of Paris: From Roast Mammoth to Steak Frites." Aside from continuing research into Parisian food history, he is also studying French bread history and early medieval food. Dining Out Before Restaurants Existed - Starting as early as the thirteenth century, inns, taverns and cabarets sold food that was varied and sometimes even sophisticated. -

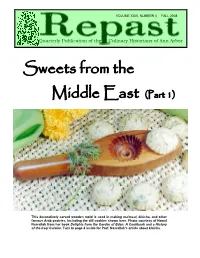

Sweets from the Middle East (Part 1)

VOLUMEVOLUME XVI, XXIV, NUMBER NUMBER 4 4 FALL FALL 2000 2008 Quarterly Publication of the Culinary Historians of Ann Arbor Sweets from the Middle East (Part 1) This decoratively carved wooden mold is used in making ma'moul, kleicha, and other famous Arab pastries, including the dill cookies shown here. Photo courtesy of Nawal Nasrallah from her book Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine. Turn to page 4 inside for Prof. Nasrallah’s article about kleicha. REPAST VOLUME XXIV, NUMBER 4 FALL 2008 Editor’s Note on Baklava Second Helpings Allowed! Charles Perry, who wrote the article “Damascus Cuisine” in our last issue, was the editor of a book Medieval Arab Cookery (Prospect Books, 2001) that sheds further light on the origins of baklava, the Turkish sweet discussed by Sheilah Kaufman in this issue. A dish described in a 13th-Century Baghdad cookery Sweets from the manuscript appears to be an early version of baklava, consisting of thin sheets of bread rolled around a marzipan-like filling of almond, sugar, and rosewater (pp. 84-5). The name given to this Middle East, Part 2 sweet was lauzinaj, from an Aramaic root for “almond”. Perry argues (p. 210) that this word gave birth to our term lozenge, the diamond shape in which later versions of baklava were often Scheduled for our Winter 2009 issue— sliced, even up to today. Interestingly, in modern Turkish the word baklava itself is used to refer to this geometrical shape. • Joan Peterson, “Halvah in Ottoman Turkey” Further information about the Baklava Procession mentioned • Tim Mackintosh-Smith, “A Note on the by Sheilah can be found in an article by Syed Tanvir Wasti, Evolution of Hindustani Sweetmeats” “The Ottoman Ceremony of the Royal Purse”, Middle Eastern Studies 41:2 (March 2005), pp. -

Changes in the Breakfast Traditions of an Old World Country

Dublin Gastronomy Symposium 2020 – Food and Disruption Changes in the Breakfast Traditions of an Old-World Country: How the Breakfast Traditions in Turkey have Changed, Causing the Loss of an Important Food Culture Banu Özden The world is changing at a very fast pace, and when it The line ‘Breakfast is the most important meal of the comes to eating habits ‘What will we eat in the future?’ day’ was invented in the 19th century by Seventh proposes a serious dilemma as well as ‘How will our eating Day Adventists James Caleb Jackson and John habits change?’ This progression into a fast-moving world, Harvey Kellogg to sell their newly invented with everchanging diets, not only threatens the way we breakfast cereal. After that, the bacon food industry grow our food but how we consume it as well. Gradually we jumped on the bandwagon and convinced people are losing our time-honored values, eating habits, traditional about the importance of eating protein in the food, and even meals such as breakfast, which has been morning (Egan, 2017). declared as the most important meal of the day for centuries. By now eating breakfast as the first meal of the day became a habit practiced all over America and Europe. History of breakfast In the same years, this new culture, based on the consumption of snacks, and the dishes that were leftover The English word, breakfast composed of two words, ‘break’ from the previous evening started to turn into a breakfast and ‘fast’ is quite self-explanatory. Not eating anything meal for the Ottomans as well. -

New York Science Journal 2017;10(6) 30 Production and Evaluation of Breakfast Cereal Flake

New York Science Journal 2017;10(6) http://www.sciencepub.net/newyork Production and Evaluation of Breakfast Cereal Flakes Using Pre-Treated Millet Sorghum Flavoured With Coconut Milk *Okafor D. C.1; Ofoedu C. E.1; Njoku N.E.1; Ibeabuchi J. C.1; Alagbaoso S. O. 1; Eluchie, C.N.1; Onyeka E. U.1; Obi, P.N.2 and Chukudobe K. C1 1Dept. of Food Science and Technology, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, P. M. B. 1526 Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria 2Department of curriculum and instruction, Alvan Ikoku Fedral Colledge of Education Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: Breakfast cereals were produced from pre-treated grains of millets (Pennisetum americanum) and Sorghum (Sorghum bicolour L Moench), flavoured with coconut milk. The chemical composition and selected functional properties as affected by the treatment given were examined. The pre -treatment of the cereals was intended to improve the nutritional constituents of the grains as well as reduce anti-nutritional factors present in the grains. The ash contents, total dietary fiber, and moisture content showed a slight increase in the sprouted product as compared to the fermented ones. On the other hand, fermented products had h igher contents of protein and fat compared to sprouted ones. Mixing of sorghum and millet gave products with higher water absorption capacity for both sprouted and fermented products. The coconut milk helped to mask the bland flavor of cereal grains as evidenced by the high sensory scores of the products in terms of aroma. In terms of overall acceptability, product from a mixture of sprouted sorghum and millet (SMS) had the highest (p=0.05) score of 7.4. -

PRODUCTION and EVALUATION of BREAKFAST CEREALS from BLENDS of AFRICAN YAM BEAN (Sphenostylis Stenocarpa), MAIZE (Zea Mays) and DEFATTED COCONUT (Cocos Nucifera)

i PRODUCTION AND EVALUATION OF BREAKFAST CEREALS FROM BLENDS OF AFRICAN YAM BEAN (Sphenostylis stenocarpa), MAIZE (Zea mays) AND DEFATTED COCONUT (Cocos nucifera). BY USMAN, GRACE OJALI PG/M.Sc./09/50997 DEPARTMENT OF FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. NOVEMBER, 2012 i TITLE PAGE PRODUCTION AND EVALUATION OF BREAKFAST CEREALS FROM BLENDS OF AFRICAN YAM BEAN (Sphenostylis stenocarpa), MAIZE (Zea mays) AND DEFATTED COCONUT (Cocos nucifera). A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF M.Sc. IN FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY. BY USMAN, GRACE OJALI PG/M.Sc./09/50997 DEPARTMENT OF FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. NOVEMBER, 2012 ii CERTIFICATION USMAN, GRACE OJALI, a Post-graduate student in the Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, with Registration Number: PG/M.Sc./09/50997 has satisfactorily completed the requirements for award of the degree of Master of Science in Food Science and Technology. The work embodied in this dissertation is original and has not been submitted in part or full for any other diploma or degree of this or other university. ------------------------------------ ------------------------------------- DR G.I OKAFOR MR C.S. BHANDARY (SUPERVISOR) (HEAD OF DEPARTMENT) ----------------------- ---------------------- Date Date iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the Holy Spirit, my source of inspiration and my family, for helping me in ways I can never quantify. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The successful completion of this research was made possible through the efforts and commitment of so many to whom I owe my appreciation. -

Winter 2009 Morsels & Tidbits

VOLUMEVOLUME XVI, XXV, NUMBER NUMBER 4 1 FALL WINTER 2000 2009 Quarterly Publication of the Culinary Historians of Ann Arbor Sweets from the Middle East (Part 2) Painting of a confectioner, or helvahâneli, in his official attire from the Topkapı imperial kitchens of Istanbul, Turkey. Joan Peterson’s article about Turkish halvah begins on page 3 inside. Image from Ottoman Costume Book: a Facsimile Edition of Osmanh Kiyafetleri by Fenerci Melmed, 1986. REPAST VOLUME XXV, NUMBER 1 WINTER 2009 MORSELS & TIDBITS Ann Fowler, a cherished veteran member of the Culinary and Wine in America: A Remarkable Story”. Curated by CHAA Historians, passed away on February 14 after a long illness. founding members Prof. Dan Longone and Jan Longone, it Ann’s devotion and unflagging service over many years will opened on February 16 and runs until May 29, 2009. The remain forever in our hearts and memories. She volunteered for a Longones will present a lecture about the exhibition, co-sponsored variety of tasks within CHAA, and was a docent at the by CHAA, on May 10 (see calendar on p. 20 for details). University of Michigan’s William L. Clements Library, where she labored to help establish and organize the culinary archives. CHAA member Ann Larimore, a professor emerita of Our deepest condolences go to Ann’s husband and fellow geography and women’s studies at the University of Michigan, CHAA member, Don Fowler. gave a talk there on March 19, “The Trouble with Tractors: Speaking up for the Ox”. Her presentation, part of the Turkish Nor is it easy to imagine the UM Clements Library without Studies Colloquium, examined what happened to traditional wheat- Jan Longone, who has made known her intention to retire there based farming villages in Turkey in the 1950’s, when tractors and later this year as Curator of American Culinary History. -

THE BREAKFAST CLUB a Cost/Benefit Analysis on the Breakfast Program at Douglas Road Elementary School

THE BREAKFAST CLUB A Cost/Benefit Analysis on the breakfast program at Douglas Road Elementary School Dr. Andrew Gemino, Ben Tan 3/01/2016 In partnership with: This report provides a cost/benefit analysis of a free, open access breakfast program called the Breakfast Club offered at Douglas Road Elementary School. Executive Summary This report provides a cost/benefit analysis of a breakfast program called the “Breakfast Club” offered at Douglas Road Elementary School. Douglas Road Elementary is a 250-student school serving kindergarten through grade 7 in Burnaby, British Columbia. The Breakfast Club offers daily breakfast free of charge to all students from kindergarten to grade 7. As of December 2015, 83 students, or 33% of the students, are registered in the program and approximately 25% of the registrants attended the Breakfast Club on any given day. The Breakfast Club was founded in October, 2014, with support from the Principal, Mrs. Mary-Ann Brown, the Burnaby School District and a private donation organized by employees of Beedie Development Group through the Vancouver Sun’s Adopt-A-School program. Canada is the only G8 country without a national school meal program and therefore partnerships such as this are key to successful meal programs. The purpose of this research study is to understand what benefits and impacts a program such as the Breakfast Club can have on students, teachers, and the school. This research also aims to provide insight into how other schools can leverage their resources into starting similar breakfast programs in the future. This study reviewed the direct cash costs and the indirect non-cash costs of the Breakfast Club. -

A Short History of Breakfast

A short history of Breakfast Introduction questions What did you eat for breakfast this morning? What might you get in a “Full English Breakfast”? Have you ever tried it? What is a traditional breakfast where you live? Breakfast Breakfast as we know it didn't exist for large parts of history. The Romans didn't really eat it, usually consuming only one meal a day around noon, says food historian Caroline Yeldham. In fact, breakfast was actively frowned upon. "The Romans believed it was healthier to eat only one meal a day," she says. "They were obsessed with digestion and eating more than one meal was considered a form of gluttony. This thinking impacted on the way people ate for a very long time." In the Middle Ages monastic life largely shaped when people ate, says food historian Ivan Day. Nothing could be eaten before morning Mass and meat could only be eaten for half the days of the year. It's thought the word breakfast entered the English language during this time and literally meant "break the night's fast". Religious ritual also gave us the full English breakfast. On Collop Monday, the day before Shrove Tuesday, people had to use up meat before the start of Lent. Much of that meat was pork and bacon as pigs were kept by many people. The meat was often eaten with eggs, which also had to be used up, and the precursor of the full English breakfast was born. But at the time it probably wasn't eaten in the morning. -

Breakfast Cereal Cultural History Dustin Goldberger May 18, 2010

Breakfast Cereal Cultural History Dustin Goldberger May 18, 2010 A Spoonful of History: Health, Wealth, and The Rise of The American Breakfast Cereal Objectives 1. Provide a comprehensive history of the dominant players in the breakfast cereal industry, from its 19 th century origins as a health food alternative to its current status as a part of the mainstream American diet. 2. Identify and discuss how a discourse that paints breakfast cereal as a health food competes with corporate needs to drive profits. 3. Assess the breakfast cereal industry’s engagement with consumers. This includes notable citizen protest against Big Cereal and the industry’s response. Summary of Findings I. Family First: The 19 th Century Origins of America’s Breakfast Staple The discourse surrounding the nutritious value of breakfast cereal has a rich historical trajectory. While today’s consumers question the motives of cereal executives who claim to provide healthy products, those who first produced cereal products seem to have sincerely felt they were essential to household health. In the mid 1800’s, the American diet was in a state of disorder. As the frontier expanded, Americans needed cheap ways to preserve food over long journeys, and could not afford to keep around perishable fruits and vegetables. For many, mornings in the West began with whiskey and men commonly came “to expect more than three sorts of meat” during supper, which was a social affair that could last as long as seven hours. 1 Not surprisingly, such a rich diet put a chokehold on American health. Nineteenth century Americans came to recognize the “difficulty of digestion or fermentation in the stomach or guts” that came from such eating as “Dyspepsia”, an affliction that had spread across the nation. -

Breakfast the Most Important Meal of the Day?

Prod:Type:FTP ED: 5þ model IJGFS : 60 pp:028ðcol:fig::NILÞ PAGN: SCAN: Available online at www.sciencedirect.com International Journal of 1 Gastronomy and Food Science 3 International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]] www.elsevier.com/locate/ijgfs 5 Review article 7 Q2 Breakfast: The most important meal of the day? 9 n Q1 Charles Spence 11 Crossmodal Research Laboratory, Oxford University, UK 13 Received 8 January 2017; accepted 25 January 2017 15 17 Abstract 19 Stating the obvious, we typically eat different foods at different times of day. But why should that be so? While much of this variation is likely down to cultural factors, the dietitians also have plenty to say on the matter of what we should be eating and drinking when, in order, for instance, to lose weight, or 21 else to help enhance our cognitive performance during the course of the day. In recent years, many of the larger food companies have become increasingly interested in trying either to break into the profitable, not to mention growing, market for breakfast foods, or else to figure out how to convince more consumers to eat ‘breakfast foods’ at other times of day. In this review, I want to take a closer look at the psychological science behind the first meal of the 23 day, highlighting why it may be even more important than most people think – both to the consumer but also the food industry more generally. Finally, I summarize a number of the current trends in the kinds of breakfast items that are becoming more/less popular, and consider what may be driving them. -

The Budget Includes Revenues from Five (5) Different Funds That Are

Table of Contents Letter of Introduction …………………..……………………………………………… 2 Definitions ……………………………………………………………………………… 3 Finance Terms ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Chapter One: District Overview ……………………………………………… 7 Demographics Enrollment Chapter Two: Budget Overview………………………………………………. 12 Chapter Three: Elementary School Report ……………………………………. 23 McKinley Lincoln Washington Wilson Chapter Four: Intermediate School Report …………………………………… 36 Willow Creek Owatonna Junior High School Chapter Five: Secondary School Report …………………………………….. 43 Owatonna Senior High School Owatonna Alternative Learning Center Chapter Six: Activities Program Report ………………………………….… 52 Chapter Seven: Special Services and Special Education Report …………… 59 Chapter Eight: Food & Nutrition and Community Education Report ………. 66 Chapter Nine: Capital Budget Overview ……………………………………… 78 Chapter Ten: Strategic Plan and Student Achievement ………………… 82 Chapter Eleven: District Benchmarks …………………………………………… 108 Chapter Twelve: Troubling Times…………………………………………….. 116 1 Tom Tapper, Ed.D. Superintendent of Schools To: Members of the School Board From: Tom Tapper, Superintendent Re: Preliminary Budget for the 2010-2011 School Year Date: June 2010 Contained within this report entitled, “Preliminary Budget for the 2010-11 School Year” is a comprehensive analysis of our budget and related activities of our school District for the past school year. This „report-out‟ of our finances and the many activities that have taken place at our various school sites is intended to give you -

History of Breakfast

History of breakfast Eating breakfast began in the Neolithic (late Stone Age) era, when large stones were used to grind grains to make a sort of porridge. Porridge was also a staple of Roman Soldiers’ diets – they called it pulmentus. During the middle ages, barley and hops were used to make beer which was served up in the morning to hungry peasants alongside oatcakes or porridge. Breakfast as we know it began in the early 19th century, when some middle-class men started to work regular hours in offices – prior to that people would often work for a few hours, then eat a meal at about 10am. Wives or kitchen staff would often serve these 19th century commuters a two-course meal that would often begin with a bowl of porridge. This would be followed by a full English breakfast: toast and eggs with bacon or fish. This style of meal wasn’t referred to as the ‘full English’ until the First World War when lighter breakfasts grew in popularity. Eating breakfast had become a more elaborate act by the 19th century, at least in well-off households. In the 1861 Book of Household Management, Isabella Beeton suggested a daily breakfast buffet that included a cold joint of meat, game pies, broiled mackerel, sausages, bacon and eggs, muffins, toast, marmalade, butter, jam, coffee and tea. Towards the end of the 1800s, there was a backlash against these kinds of lavish diets. Groups like the 7th Day Adventists protested that meat-based breakfasts were leading to ill health! Over the next few decades, pioneers like John Kellogg, W.K.