Sri Lanka: Background and U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remarks by Hon. Rohitha Bogollagama Minister for Foreign Affairs “Financing Strategies for Healthcare”, 16Th March 2009

Welcome remarks by Hon. Rohitha Bogollagama Minister for Foreign Affairs “Financing Strategies for Healthcare”, 16th March 2009 Hon. Prime Minister, Ratnasiri Wickremanayake, Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Healthcare and Nutrition, Distinguished Ministers, Representatives from UNDESA and WHO Excellencies, Representatives of UN Agencies, Distinguished Delegates, It is my great pleasure to welcome you to Colombo to the “Regional Ministerial Meeting on Financing Strategies for Healthcare”. I am particularly pleased to see participation from such a wide spectrum of stake-holders relevant to this meeting, including distinguished Ministers, Senior Officials, Representatives of UN Secretariat and agencies, Multilateral Organizations, NGOs and the Private Sector. This broad-based participation will enable us to address, from several perspectives, the challenges related to the subject of this Regional Meeting, the objective of which is to realize the health-related MDGS for the benefit of our people. I welcome in particular the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Myanmar, Minister of Health of Maldives, Minister of Finance of Bhutan and the Deputy Ministers of Mongolia and Kyrgyzstan and who have taken time off their busy schedules to gather here in Colombo. This meeting is organized under the framework of Annual Ministerial Review process of the Economic Social Council of the UN. The primary responsibility for overseeing progress in the achievement of the MDG’s by 1 the year 2015 devolves on the ECOSOC, and the Annual Ministerial Review process was established to monitor our progress in this regard. The theme for Review at Ministerial level at the ECOSOC in July this year is how we can work together to achieve the internationally agreed goals and commitments regarding global public health. -

Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism

DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM SRI LANKAN DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM By MYRA SIVALOGANATHAN, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Myra Sivaloganathan, June 2017 M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Sri Lankan Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism AUTHOR: Myra Sivaloganathan, B.A. (McGill University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Mark Rowe NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 91 ii M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. Abstract In this thesis, I argue that discourses of victimhood, victory, and xenophobia underpin both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalist and religious fundamentalist movements. Ethnic discourse has allowed citizens to affirm collective ideals in the face of disparate experiences, reclaim power and autonomy in contexts of fundamental instability, but has also deepened ethnic divides in the post-war era. In the first chapter, I argue that mutually exclusive narratives of victimhood lie at the root of ethnic solitudes, and provide barriers to mechanisms of transitional justice and memorialization. The second chapter includes an analysis of the politicization of mythic figures and events from the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahāvaṃsa in nationalist discourses of victory, supremacy, and legacy. Finally, in the third chapter, I explore the Liberation Tiger of Tamil Eelam’s (LTTE) rhetoric and symbolism, and contend that a xenophobic discourse of terrorism has been imposed and transferred from Tamil to Muslim minorities. Ultimately, these discourses prevent Sri Lankans from embracing a multi-ethnic and multi- religious nationality, and hinder efforts at transitional justice. -

US Job Loss Far Worse Than Indicated

OPPOSITION TO MOVE COURT POLITICAL MATURITY OF OVER PARLIAMENT RECALL SRI LANKA'S LEADERS PUT TO THE TEST MAY THE POWER 01 - 03, 2020 OF PAPER VOL: 4- ISSUE 193 . 30 ‘UTTER DISASTER' PASSIONS AND GLOCAL PAGE 03 HOT TOPICS PAGE 04 COMMENTARY PAGE 06 PERSONALITIES PAGE 08 Registered in the Department of Posts of Sri Lanka under No: QD/144/News/2020 COVID-19 and curfew in Sri Lanka • 14 people were confirmed as COVID-19 positive yester- day (April 30), taking Sri Lanka’s tally of the novel coro- navirus infection to 663. 502 individuals are receiving treatment, 154 have been deemed completely recovered and seven have succumbed to the virus. • An all island curfew was imposed from 8:00 p.m. yes- terday till 5:00 a.m. Monday (4). • Of the 997 navy personnel tested for COVID-19, 159 were confirmed as positive with 80% being asympto- matic. • Of the 21,000 PCR tests carried out in Sri Lanka so far, 3% have been confirmed as positive. • The Civil Aviation Authority has invited drone opera- tors to join the fight against COVID-19. • Police say no decision has been taken so far to extend the curfew in areas deemed as high risk, till May 31 though it was announced that curfew passes issued for essential services that ended yesterday could be used till the end of May. • Postmaster General RanjithAriyaratne has announced that all post offices will be opened from Monday for reg- ular services. He has requested public to follow health advices when visiting post offices and obtaining services. -

Sri Lanka's General Election 2015 Aliff, S

www.ssoar.info Sri Lanka's general election 2015 Aliff, S. M. Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Aliff, S. M. (2016). Sri Lanka's general election 2015. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, 68, 7-17. https://doi.org/10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILSHS.68.7 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences Submitted: 2016-01-12 ISSN: 2300-2697, Vol. 68, pp 7-17 Accepted: 2016-02-10 doi:10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILSHS.68.7 Online: 2016-04-07 © 2016 SciPress Ltd., Switzerland Sri Lanka’s General Election 2015 SM.ALIFF Head, Dept. of Political Science, Faculty of Arts & Culture South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, Oluvil Sri Lanka [email protected] Keywords: Parliamentary election of Sri Lanka 2015, Politics of Sri Lanka, Political party, Proportional Representation, Abstract Sri Lanka emerges from this latest election with a hung Parliament in 2015. A coalition called the United National Front for Good Governance (UNFGG) won 106 seats and secured ten out of 22 electoral districts, including Colombo to obtain the largest block of seats at the parliamentary polls, though it couldn’t secure a simple majority in 225-member parliament. It also has the backing of smaller parties that support its agenda of electoral. -

269 Abdul Aziz Angkat 17 Abdul Qadir Baloch, Lieutenant General 102–3

Index Abdul Aziz Angkat 17 Turkmenistan and 88 Abdul Qadir Baloch, Lieutenant US and 83, 99, 143–4, 195, General 102–3 252, 253, 256 Abeywardana, Lakshman Yapa 172 Uyghurs and 194, 196 Abu Ghraib 119 Zaranj–Delarum link highway 95 Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) 251, 260 Africa 5, 244 Abuza, Z. 43, 44 Ahmad Humam 24 Aceh 15–16, 17, 31–2 Aimols 123 armed resistance and 27 Akbar Khan Bugti, Nawab 103, 104 independence sentiment and 28 Akhtar Mengal, Sardar 103, 104 as Military Operation Zone Akkaripattu- Oluvil area 165 (DOM) 20, 21 Aksu disturbances 193 peace process and Thailand 54 Albania 194 secessionism 18–25 Algeria Aceh Legislative Council 24 colonial brutality and 245 Aceh Monitoring Mission (AMM) 24 radicalization in 264 Aceh Referendum Information Centre Ali Jan Orakzai, Lieutenant General 103 (SIRA) 22, 24 Al Jazeera 44 Acheh- Sumatra National Liberation All Manipur Social Reformation, women Front (ASNLF) 19 protesters of 126–7 Aceh Transition Committee (Komite All Party Committee on Development Peralihan Aceh) (KPA) 24 and Reconciliation ‘act of free choice’, 1969 Papuan (Sri Lanka) 174, 176 ‘plebiscite’ 27 All Party Representative Committee Adivasi Cobra Force 131 (APRC), Sri Lanka 170–1 adivasis (original inhabitants) 131, All- Assam Students’ Union (AASU) 132 132–3 All- Bodo Students’ Union–Bodo Afghanistan 1–2, 74, 199 Peoples’ Action Committee Balochistan and 83, 100 (ABSU–BPAC) 128–9, 130 Central Asian republics and 85 Bansbari conference 129 China and 183–4, 189, 198 Langhin Tinali conference 130 India and 143 al- Qaeda 99, 143, -

Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : a Finding Aid

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids and Research Guides for Finding Aids: All Items Manuscript and Special Collections 5-1-1994 Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives. James Anthony Schnur Hugh W. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all Part of the Archival Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives.; Schnur, James Anthony; and Cunningham, Hugh W., "Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid" (1994). Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items. 19. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all/19 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids and Research Guides for Manuscript and Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection A Finding Aid by Jim Schnur May 1994 Special Collections Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg 1. Introduction and Provenance In December 1993, Dr. Hugh W. Cunningham, a former professor of journalism at the University of Florida, donated two distinct newspaper collections to the Special Collections room of the USF St. Petersburg library. The bulk of the newspapers document events following the November 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. A second component of the newspapers examine the reaction to Richard M. Nixon's resignation in August 1974. -

Country of Origin Information Report Sri Lanka May 2007

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT SRI LANKA 11 MAY 2007 Border & Immigration Agency COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE 11 MAY 2007 SRI LANKA Contents PREFACE Latest News EVENTS IN SRI LANKA, FROM 1 APRIL 2007 TO 30 APRIL 2007 REPORTS ON SRI LANKA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 1 AND 30 APRIL 2007 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY........................................................................................ 1.01 Map ................................................................................................ 1.06 2. ECONOMY............................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY.............................................................................................. 3.01 The Internal conflict and the peace process.............................. 3.13 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS...................................................................... 4.01 Useful sources.............................................................................. 4.21 5. CONSTITUTION..................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM .............................................................................. 6.01 Human Rights 7. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................... 7.01 8. SECURITY FORCES............................................................................... 8.01 Police............................................................................................ -

African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries Compiled by Mette Shayne Revised Summer 1999

African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries Compiled by Mette Shayne Revised Summer 1999 INTRODUCTION This union list updates African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries compiled by Daniel A. Britz, Working Paper no. 8 African Studies Center, Boston, 1979. The holdings of 19 collections and the Foreign Newspapers Microfilm Project were surveyed during the summer of 1999. Material collected currently by Library of Congress, Nairobi (marked DLC#) is separated from the material which Nairobi sends to Library of Congress in Washington. The decision was made to exclude North African papers. These are included in Middle Eastern lists and in many of the reporting libraries entirely separate division handles them. Criteria for inclusion of titles on this list were basically in accord with the UNESCO definition of general interest newspapers. However, a number of titles were included that do not clearly fit into this definition such as religious newspapers from Southern Africa, and labor union and political party papers. Daily and less frequently published newspapers have been included. Frequency is noted when known. Sunday editions are listed separately only if the name of the Sunday edition is completely different from the weekday edition or if libraries take only the Sunday or only the weekday edition. Microfilm titles are included when known. Some titles may be included by one library, which in other libraries are listed as serials and, therefore, not recorded. In addition to enabling researchers to locate African newspapers, this list can be used to rationalize African newspaper subscriptions of American libraries. It is hoped that this list will both help in the identification of gaps and allow for some economy where there is substantial duplication. -

Family Planning in Ceylon1

1 [This book chapter authored by Shelton Upatissa Kodikara, was transcribed by Dr. Sachi Sri Kantha, Tokyo, from the original text for digital preservation, on July 20, 2021.] FAMILY PLANNING IN CEYLON1 by S.U. Kodikara Chapter in: The Politics of Family Planning in the Third World, edited by T.E.Smith, George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London, 1973, pp 291-334. Note by Sachi: I provide foot note 1, at the beginning, as it appears in the published form. The remaining foot notes 2 – 235 are transcribed at the end of the article. The dots and words in italics, that appear in the text are as in the original. No deletions are made during transcription. Three tables which accompany the article are scanned separately and provided. Table 1: Ceylon: population growth, 1871-1971. Table 2: National Family Planning Programme: number of clinics and clinic-population ratio by Superintendent of Health Service (SHS) Area, 1968-9. Table 3: Ceylon: births, deaths and natural increase per 1000 persons living, by ethnic group. The Table numbers in the scans, appear as they are published in the book; Table XII, Table XIII and Table XIV. These are NOT altered in the transcribed text. Foot Note 1: In this chapter the following abbreviations are used: FPA, Family 2 Planning Association, LSSP, Lanka Samasamaja Party, MOH, Medical Officer of Health, SLFP, Sri Lanka Freedom Party; SHS, Superintendent of Health Services; UNP, United National Party. Article Proper The population of Ceylon has grown rapidly over the last 100 years, increasing more than four-fold between 1871 and 1971. -

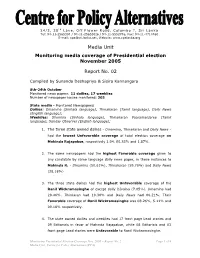

Monitoring Media Coverage of Presidential Election November 2005

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Report No. 02 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara 8th-24th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 205 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); 1. The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.04. 00.33% and 1.87%. 2. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda R. - Dinamina (50.61%), Thinakaran (59.70%) and Daily News (38.18%) 3. The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe of except daily DIvaina (7.05%). Dinamina had 29.46%. Thinkaran had 10.30% and Daily News had 06.21%. Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe was 08.26%, 5.11% and 09.18% respectively. 4. The state owned dailies and weeklies had 17 front page Lead stories and 09 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 08 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. Monitoring Presidential Election Coverage Nov. -

Daily Express 20042020

EUROPE VIRUS TOLL TOPS 100,000 GOVT. BANS A WIDE AN INSIDER CALLS MONDAY AS ONLINE MEGA-CONCERT RANGE OF IMPORTS AMID FOR HELP APRIL 20, 2020 RAISES SPIRITS CORONAVIRUS CRISIS VOL: 4 - ISSUE 346 HOT TOPICS PAGE 04 COMMENTARY 30. PAGE 02 PAGE 03 GLOCAL Registered in the Department of Posts of Sri Lanka under No: QD/146/News/2020 COVID-19 and curfew in Sri Lanka • 15 more patients were confirmed as COVID-19 positive yesterday (19), taking Sri Lanka’s tally of the novel coro- navirus infection to 269. One hundred and fifty six indi- viduals are receiving treatment, 122 are under observation, 91 have been deemed completely recovered and seven have succumbed to the virus. • The 24-hour indefinite curfew in 19 out of the 25 districts will be removed at dawn today (20), replaced by a nine- hour night curfew (8:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m.). -Six districts, including Colombo, Gampaha, Kalutara, Put- talam, Ampara and Kandy will see lockdown measures re- laxed from Wednesday (22), but night curfews will be im- posed until further notice. • A ban on public meetings, religious gatherings and pro- cessions will remain, with schools and universities closed until further notice. • Those with suspected COVID-19 symptoms are urged to call 1390 - emergency hotline- set up for free medical ad- vice and assistance, and to facilitate hospital admissions. • Sri Lanka College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has set up a 24-hours hotline – 0710301225- for pregnant women to address issues faced by them including COV- ID-19 infection and pregnancy related complications. -

Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka

Policy Studies 40 Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka Neil DeVotta East-West Center Washington East-West Center The East-West Center is an internationally recognized education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen understanding and relations between the United States and the countries of the Asia Pacific. Through its programs of cooperative study, training, seminars, and research, the Center works to promote a stable, peaceful, and prosperous Asia Pacific community in which the United States is a leading and valued partner. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, private foundations, individuals, cor- porations, and a number of Asia Pacific governments. East-West Center Washington Established on September 1, 2001, the primary function of the East- West Center Washington is to further the East-West Center mission and the institutional objective of building a peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community through substantive programming activities focused on the themes of conflict reduction, political change in the direction of open, accountable, and participatory politics, and American under- standing of and engagement in Asia Pacific affairs. Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka Policy Studies 40 ___________ Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka ___________________________ Neil DeVotta Copyright © 2007 by the East-West Center Washington Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka By Neil DeVotta ISBN: 978-1-932728-65-1 (online version) ISSN: 1547-1330 (online version) Online at: www.eastwestcenterwashington.org/publications East-West Center Washington 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, D.C.