Bickley & Corrall (2011) E-Print

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report to City Centre, South & East Planning and Highways Area Board

SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL Development, Environment and Leisure Directorate REPORT TO CITY CENTRE, SOUTH & DATE 19/06/2006 EAST PLANNING AND HIGHWAYS AREA BOARD REPORT OF DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT SERVICES ITEM SUBJECT APPLICATIONS UNDER VARIOUS ACTS/REGULATIONS SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS SEE RECOMMENDATIONS HEREIN THE BACKGROUND PAPERS ARE IN THE FILES IN RESPECT OF THE PLANNING APPLICATIONS NUMBERED. FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS N/A PARAGRAPHS CLEARED BY BACKGROUND PAPERS CONTACT POINT FOR ACCESS Howard Baxter TEL NO: 0114 2734556 Chris Heeley 0114 2736329 AREA(S) AFFECTED CATEGORY OF REPORT OPEN Application No. Location Page No. 04/04633/CAC Site Of Former Richardsons Cutlery Russell Street And Cotton Street And, Alma Street, 5 Sheffield, 04/04634/FUL Site Of Former Richardsons Cutlery Russell Street And Cotton Street And, Alma Street, 7 Sheffield, 04/04689/FUL Mylnhurst Convent School & Nursery, Button Hill, Sheffield, S11 9HJ 9 05/01274/FUL Crookesmoor House, 483 Crookesmoor Road, Sheffield, S10 1BG 22 05/01279/LBC Crookesmoor House, 483 Crookesmoor Road, Sheffield, S10 1BG 41 05/03455/FUL Site Of 32, Ryegate Road, Sheffield, 45 05/03489/OUT 89 London Road, Sheffield, S2 4LE 56 05/04913/FUL Land Adjacent To Vine Grove Farm, School Street, Mosborough, Sheffield, 66 06/00268/FUL Land At Blast Lane And, Broad Street, Sheffield, 74 06/00546/FUL 336 Ringinglow Road, Sheffield, S11 7PY 96 06/00642/OUT Site Of 2a, Cadman Street, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 5BU 108 06/00731/FUL 69 High Street, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 5AF 112 06/00821/FUL Former Grahams -

Self Guided Campus Tour.Pdf

To The University of Sheffield 5. Western Bank Library 12. The Diamond Discover And Sheffield gained its Royal Charter to open as a University Understand. Primarily used by final year and postgraduate students, Western This £81 million building – our largest ever investment in in 1905. When it first opened the University had only 363 Bank Library was the main University library until the opening teaching and learning - has created a fantastic place for modern students and 71 members of staff. We now have 26,000 of the Information Commons. The University’s libraries are on interdisciplinary teaching. As well as specialist Engineering students and 7,200 staff based in buildings on over a mile a number of sites and hold over 1.3 million printed volumes, as teaching facilities the building is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a long stretch of campus. well as an extensive range of high quality electronic resources. week and houses a range of lecture theatres, seminar rooms, open-plan learning spaces, library services and social spaces - The University of Sheffield is recognised as being one of available to all students. CAMPUS the original ‘redbrick’ institutions. It is a member of the 6. The Arts Tower prestigious Russell Group, which is comprised of 24 major 13. St George’s Church research-led UK Universities. The University is made up This Grade II listed building is now mainly an administration block, although the School of Architecture still occupies the Self of 50 academic departments which are grouped into top floors. At 78m high, the Arts Tower is the tallest University St George’s is an old Church of England church which was built five faculties: Arts & Humanities; Engineering; Medicine, building in the country and was Sheffield’s tallest building until in 1821. -

Self Guided Campus Tour

The University of Sheffield 4. Alfred Denny Building 11. Jessop Building Sheffield gained its Royal Charter to open The Alfred Denny Building is home to the Departments Previously the Victoria Wing of Sheffield’s as a University in 1905. When it first opened, of Animal & Plant Sciences and Biology. It’s also home to Jessop Maternity Hospital, the University has the University had only 363 students and the Alfred Denny Museum, which contains specimens of been careful to retain the look and feel of this 71 members of staff. We now have almost animals from across the globe and letters from Charles building which is intrinsically linked with the 28,000 students and over 8,000 staff based Darwin written to Henry Denny (Alfred Denny’s father). city. It now houses offices and practise/teaching in buildings on over a mile long stretch of The museum is open on the first Saturday of each rooms for the Department of Music. campus. month for guided tours. 12. The Diamond The University of Sheffield is recognised 5. Western Bank Library This £81 million building – our largest ever as being one of the original ‘redbrick’ Western Bank Library is a Grade II listed building. It investment in teaching and learning – has created institutions. It is a member of the prestigious contains 1.2 million texts and has 730 study spaces. a fantastic place for modern interdisciplinary Self Russell Group, which is comprised of 24 The library backs onto Weston Park providing great teaching. As well as containing specialist major research-led UK universities. -

University of Sheffield Events

Music Drama Lectures, Seminars & Conferences Open Days, Exhibitions & Fairs Open Campus 50 Years of October 2010 –– January 2011 Western Bank Library 19 October - 14 January Gay Icons Project 19 November - University 11 December y b y Of r e l l a G n o i t i b i h x E y r Sheffield a r b i L k n r a e n B o n o r p e t S s e n a I Events. W Download a PDF of this booklet at: www.sheffield.ac.uk/whatson/opencampus.html For more information on events at the University of Sheffield see: www.sheffield.ac.uk/whatson The Million CELEBRATING 50 YEARS established Modernism in Britain, OF WESTERN BANK LIBRARY Gollins Melvin Ward and Partners Book Library designed a library of pure cubic TUESDAY 19 OCTOBER – form, inspired by one of the 19 October 10 - FRIDAY 14 JANUARY 2011. pioneering masters of Modern 14 January 11 9.00am – 9.00pm Monday to Friday; architecture, Ludwig Mies van 10.00am to 6.00pm Saturdays & der Rohe. Join the University and Sundays. Exhibition closed from Library as they mark this special 5pm Friday 24 December - to occasion, by visiting the exhibition. 9.00am - Tuesday 4 January 2011 Take a journey through the historical development of the Western Bank Library, S10 2TN Western Bank site, see the architectural vision of Gollins The 1950s saw both an expansion Melvin Ward and discover the in student numbers and a changing face of the University’s growing collection of books at the Libraries in the 21st Century. -

Snakes and League Table Ladders Pdf, 1.52MB

Snakes and League Table Ladders The Value of Campus Facilities In The Student Experience September, 2018 The Value Of Campus Facilities In The Student Experience September, 2018 Contents Hassell Contact 61 Little Collins Street Michaela Sheahan Melbourne VIC Australia 3000 Senior Researcher T +61 3 8102 3000 [email protected] hassellstudio.com +61 03 8102 3132 @hassell_studio 1. Headline Findings 4 2. Who's Measuring What? 6 3. National Surveys Analysis 8 4. What Role Do Facilities Play? 15 5. Case Studies 18 6. Conclusion 32 7. References 33 Hassell believes that good Acknowledgements University of Leeds, United Kingdom We would like to thank the university – Stewart Ross, Director, Commercial and design can positively representatives for their time and insights: Campus Services; Michele Troughton, Head of Estate Planning; Michael Fake, Head of influence the student UCL (University College London), United Learning and Customer Services (Library; Kingdom Joanna Hynes, Deputy Director, Campus experience. – Ben Meunier, Director of Operations, Library Support Services Services,; Jay Woodhouse, Facilities and This research explores Project Manager, Library Services; June University of Newcastle, Australia Hedges, Head of Liaison and Support Mark Kirby, Manager, Planning and Quality how the student Services, Library Services; Katherine Fletcher, Senior Academic Planning – Greg Anderson, University Librarian; Meri experience is measured, Coordinator, UCL East Butler, Campus Strategy Manager; Professor Liz Burd, Pro Vice Chancellor (Learning and and the importance that University of New South Wales, Australia Teaching) universities and student – Professor Geoff Crisp, Pro Vice Chancellor University of Surrey, United Kingdom (Education) place, amongst all the – Michele Facer, Head of Strategic Space University of Sheffield, United Kingdom Management; Craig Lowe, Head of Student Support Services; Dr. -

Sheffield's Language Education Policies

Rev 28.11.08 Council of Europe CITY REPORT Sheffield’s Language Education Policies Cllr M. Reynolds January 2008 Final pre visit report 28.11.08 Council of Europe City Report: Sheffield’s Language Education Policies CONTENTS Section 1 Factual Description of Sheffield Page 1.1 Sheffield- general overview 6 1.2 Sheffield’s economy 8 1.3 Sheffield – ethnic composition and diversity 10 1.4 Sheffield – political and socio-economic structures 13 1.4.1 Political structures and composition 13 1.4.2 Social division 15 1.4.3 ‘Sheffield First’ 17 1.4.4 ‘Creative Sheffield’ 17 1.4.5 Sheffield Chamber of Commerce and Industry 18 1.5 Sheffield – home languages spoken by children 19 1.6 Policies and responsibilities for Language Teaching 21 1.6.1 Preface 21 1.6.2 Responsibilities for education 21 1.6.3 The education system in England 22 1.6.4 Types of school in England 23 1.6.4.1 Maintained 23 1.6.4.2 Other types of school 25 1.6.5 Current curriculum debates 26 1.6.6 Language education policy: the National Languages Strategy (2002) 27 1.6.7 Policy implementation 28 1.6.8 Higher education networks 29 1.6.9 Innovations in approaches to language education 30 1.7 Education in Sheffield 32 1.7.1 Children and Young People’s Directorate 32 1.7.2 Sheffield’s schools 34 1.7.3 ‘Transforming Learning Strategy’ 35 1.8 Teachers 36 1.8.1 Teacher training structures 36 1.8.2 Methodological approaches to language teaching 37 1.8.2.1 Primary 37 1.8.2.2 Secondary (Key Stage 3) 38 1.8.2.3 Secondary (Key Stage 4) 40 1.8.2.4 Beyond 16 40 2 Final pre visit report 28.11.08 -

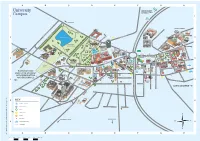

Download Our Campus Map with A-Z Index

0–9 F O 301: Student Skills and Development Centre E4 149 Faculty Offices Octagon Centre D4 118 > Arts and Humanities F3 195 Ophthalmology and Orthoptics C5 88 A > Engineering H3 210 ENGLISH LANGUAGE > Medicine, Dentistry and Health C5 92 TEACHING CENTRE P Academic Unit of Clinical Oncology B4 41 > Science E3 113 (see Central Sheffield Academic Unit of Medical Education C5 88 Pam Liversidge Building H2 174 map overleaf) > Social Sciences G3 197 University Accommodation and Commercial Services Perak Laboratories E3 110 St Vincent’s Accommodation Finance Department E2 104 (see Central Sheffield map) 10 Firth Court D3 105 Philippa Cottam Communication Clinic C3 37 3 Solly Street Addison Building D3 113 Firth Hall D3 105 Philosophy G4 161 Campus Adult Dental Care C4 47 University of Sheffield Florey Building D3 114 Physics and Astronomy E3 121 International College (USIC) Aerospace Engineering H3 170 French F3 184 Planning and Governance Services F4 156 Alfred Denny Building E3 111 Politics B3 31 NCP Solly Street car park Allen Court F2 198 (see City Centre map overleaf) G Polymer Centre E3 117 Amy Johnson Building H3 173 Gatehouse H2 201 Portobello Centre H3 177 Animal and Plant Sciences E3 111 Genomic Medicine C4 87 Print and Design Solutions E3 151 Antibody Resource Centre D3 108 Geography and Urban Planning D2 102 Psychology (see Central Sheffield map) 205 Archaeology G4 163 George Porter Building H2 190 Architecture E2 104 Germanic Studies F3 184 R Arthur Willis Environment Centre A3 28 Glossop Road Student Accommodation D5 200 Ranmoor Student -

18 Ashgate Road Broomhill, Sheffield S10 3BZ

18 Ashgate Road Broomhill, Sheffield S10 3BZ An outstanding Regency townhouse offering a vast range of deceptively spacious accommodation laid out over three floors. This freehold property has a Grade II listing. It is suggested that there is extra space for accommodation via the substantial loft and the extensive basement rooms which all have natural light. Obviously, the necessary consents would have to be acquired. Grade II listed Georgian townhouse with original features Accommodation over three floors Vast potential in substantial loft and basement for more accommodation subject to the necessary consents Six/seven large bedrooms Three bathrooms and two further WCs Massive reception hall with cantilevered staircase running throughout the home Lovely drawing room with high ceiling Knocked through breakfast kitchen offering excellent proportions and an open plan space Heart of Broomhill location close to excellent amenities and schooling No chain Gas central heating system EPC rating D Location Ashgate Road is a short no through road accessed from the B6547 Glossop Road close to its junction with Fulwood Road. No. 18 is the second to last house on the run of Georgian townhouses on the right hand side with access at the rear to Ashgate Lane. The property is situated in the very heart of this thriving and fashionable area located on the edge of Sheffield’s city centre and offering an excellent range of amenities including some award winning restaurants, public houses and regular transport links to and from the city. The schooling in Broomhill is superb with King Edward VII’s Upper School, Sheffield Girls High, Westbourne and Birkdale all being within walking distance and there is also Broomhill Infants School situated on Beech Hill Road. -

Download a PDF Copy of the Directory of Library Codes

November, 2018 DIRECTORY OF LIBRARY CODES www.bl.uk/librarycodes AB/C-1 University of Wales Policy: G Llyfrgell Thomas Parry Library Phone: 01970 621871 Llanbadarn Fawr ABERYSTWYTH Fax: 01970 622190 Ceredigion Email: [email protected] SY23 3AS United Kingdom AB/N-1 National Library of Wales Policy: SL2 Interlibrary Loans Phone: 01970 632933 ABERYSTWYTH Ceredigion Fax: 01970 615709 SY23 3BU Email: [email protected] United Kingdom AB/U-1 Aberystwyth University Policy: J2 The Hugh Owen Library Phone: 01970 622398 Penglais ABERYSTWYTH Fax: 01970 622404 Ceredigion Email: [email protected] SY23 3DZ United Kingdom AD/P-1 Apply to QZ/P22 AD/R-1 The James Hutton Institute Policy: G2 Gabrielle Rakotoarivony - Library Phone: 0844 9285428 Craigiebuckler ABERDEEN Fax: 0844 9285429 Aberdeenshire Email: [email protected] AB15 8QH United Kingdom AD/R-2 University of Aberdeen Rowett Institute of Nutrition and H Policy: G2 Reid Library Phone: 01224 712751 Greenburn Road Bucksburn Fax: 01224 715349 ABERDEEN Email: [email protected] Aberdeenshire AB21 9SB United Kingdom AD/U-1 Apply to AD/U-3 AD/U-2 Apply to AD/U-3 AD/U-3 University of Aberdeen Policy: J2 Sir Duncan Rice Library Phone: 01224 273330 Bedford Road ABERDEEN Fax: 01224 487048 Aberdeenshire Email: [email protected] AB24 3AA United Kingdom AD/U-5 Apply to AD/U-3 AD/U-6 Apply to AD/U-3 AD/U-7 University of Aberdeen Policy: G2 Interlibrary Loans Phone: 01224 552488 Medical School Library Foresterhill Fax: 01224 685157 ABERDEEN Email: [email protected] AB25 2ZD -

The University of Sheffield Index

Index The University of Sheffield Map Number Grid Reference Faculty offices Parking Services G1 190 > Arts and Humanities F3 184 Perak Laboratories D2 110 > Engineering H2 170 Philippa Cottam Communication Clinic B4 51 > Medicine, Dentistry and Health B5 88 Philosophy F3 161 > Science E2 117 Physics and Astronomy E3 121 > Social Science G3 197 Planning and Governance Services F4 174 Finance Department E4 139 Politics A2 31 95 Firth Court D3 105 Polymer Centre (Research) E2 117 Academic Secretary’s Office F4 174 Firth Hall D3 105 Portering Services D4 149 University parking Bus stop Academic Unit of Clinical Oncology A4 41 Florey Building D3 114 Portobello Centre H3 177 Academic Unit of Medical Education D5 141 French F3 184 Postgraduate Student Enquiries D3 120 (permit only) and service number Accommodation and Commercial Services 10 Print and Design Solutions D2 151 Addison Building D3 113 Probability and Statistics E3 121 Admissions Section C4 66 Genomic Medicine B5 87 propertywithUS D3 119 Adult Dental Care B4 47 Geography D2 102 Psychology B3 34 Aerospace Engineering H2 170 George Porter Building G1 190 Procurement and Supplies E4 139 Alfred Denny Building D3 111 Germanic Studies F3 184 Pure Mathematics E3 121 Alumni Relations E4 147 Goodwin Sports Centre A2 30 Supertram stop Banks with Amy Johnson Building H3 173 Graduate Research Centre Animal and Plant Sciences D3 111 > North Campus H1 193 Recruitment Support C4 72 and name cash dispensers Antibody Resource Centre D2 108 Graduate Research Office E4 147 Regent Court G3 166 Applied Mathematics -

University Campus

0–9 F O 301: Student Skills and Development Centre E4 149 Faculty Ofces Occupational Health Unit (HR) E2 104 > Arts and Humanities F3 195 Octagon Centre D4 118 ENGLISH LANGUAGE A > Engineering H3 170 Ophthalmology and Orthoptics C5 88 University TEACHING CENTRE Academic Unit of Clinical Oncology B4 41 > Medicine, Dentistry and Health C5 92 (see Central Sheffield > Science E3 113 P map overleaf) Academic Unit of Medical Education C5 88 Accommodation and Commercial Services > Social Sciences G3 197 Pam Liversidge Building H2 174 Campus Finance Department E2 104 (see Central Shefeld map) 10 Parking Services H2 190 Firth Court D3 105 Addison Building D3 113 Perak Laboratories E3 110 Firth Hall D3 105 Adult Dental Care C4 47 Philippa Cottam Communication Clinic C3 37 Florey Building D3 114 Aerospace Engineering H3 170 French F3 184 Philosophy G4 161 Alfred Denny Building E3 111 Physics and Astronomy E3 121 Allen Court F2 198 G Planning and Governance Services F4 156 Alumni Relations F4 160 Politics B3 31 Garden Street Laboratories H2 193 Amy Johnson Building H3 173 Gatehouse H2 201 Polymer Centre E3 117 Animal and Plant Sciences E3 111 Genomic Medicine C4 87 Portering Services E2 104 Antibody Resource Centre D3 108 Geography and Urban Planning D2 102 Portobello Centre H3 177 Archaeology H3 180 George Porter Building H2 190 Print and Design Solutions E3 151 Architecture E2 104 Germanic Studies F3 184 PropertywithUS E4 120 Arthur Willis Environment Centre A3 28 Glossop Road Student Accommodation D5 200 Psychology C3 34 Arts Tower E2 104 Goodwin -

The Graduate Guide Contents Welcome to Your Alumni* Community Your Future Graduation Is a Time for 4

Development Alumni Relations & Events. The Graduate Guide Contents Welcome to your alumni* community Your Future Graduation is a time for 4 .........Life After Graduation celebrating your success and 6 .........Your Careers Service looking to the future. You are part 7 .........Choosing a Career of a global family of over 160,000 8 .........Job Hunting Sheffield alumni from more than 9 .........Making Applications 180 countries. From Nobel Prize 10 ....... University of Sheffield winners to Olympic champions, Enterprise Sheffield’s graduates are helping to 12 ........Postgraduate Study shape the world we live in. But graduation is just the Your Sheffield beginning. In The Graduate Guide 14........ Students’ Union Life you will find advice on everything Membership Gold from getting a job, to setting up 15 ........Shop your own enterprise, to taking a 16........Reunions and Events gap year or doing further study. 18 .......Volunteering You can also find information 20 ......Supporting Your University on how to continue to engage 22 .......Outstanding Alumni with your University by attending 24 .......Exclusive Alumni Benefits events, supporting current 26 .......Reasons to be Proud students and making the most of 27 .......Your Alumni Community your alumni benefits. We look forward to seeing or hearing from you soon. With very best wishes Claire Rundström Head of Alumni Relations * Alumnus or (fem) alumna n, pl ni or nae – A graduate or former student of a school, college or university. From the Latin: nursling, pupil, foster son, from alere to nourish. Your Future 2 3 Life After Graduation We asked recent graduates for their top tips for life after University: 2.