China's Rising Demand for Minerals and Emerging Global Norms and Practices in the Mining Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agreements That Have Undermined Venezuelan Democracy Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxthe Chinaxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Deals Agreements That Have Undermined Venezuelan Democracy

THE CHINA DEALS Agreements that have undermined Venezuelan democracy xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxThe Chinaxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Deals Agreements that have undermined Venezuelan democracy August 2020 1 I Transparencia Venezuela THE CHINA DEALS Agreements that have undermined Venezuelan democracy Credits Transparencia Venezuela Mercedes De Freitas Executive management Editorial management Christi Rangel Research Coordinator Drafting of the document María Fernanda Sojo Editorial Coordinator María Alejandra Domínguez Design and layout With the collaboration of: Antonella Del Vecchio Javier Molina Jarmi Indriago Sonielys Rojas 2 I Transparencia Venezuela Introduction 4 1 Political and institutional context 7 1.1 Rules of exchange in the bilateral relations between 12 Venezuela and China 2 Cash flows from China to Venezuela 16 2.1 Cash flows through loans 17 2.1.1 China-Venezuela Joint Fund and Large 17 Volume Long Term Fund 2.1.2 Miscellaneous loans from China 21 2.2 Foreign Direct Investment 23 3 Experience of joint ventures and failed projects 26 3.1 Sinovensa, S.A. 26 3.2 Yutong Venezuela bus assembly plant 30 3.3 Failed projects 32 4 Governance gaps 37 5 Lessons from experience 40 5.1 Assessment of results, profits and losses 43 of parties involved 6 Policy recommendations 47 Annex 1 52 List of Venezuelan institutions and officials in charge of negotiations with China Table of Contents Table Annex 2 60 List of unavailable public information Annex 3 61 List of companies and agencies from China in Venezuela linked to the agreements since 1999 THE CHINA DEALS Agreements that have undermined Venezuelan democracy The People’s Republic of China was regarded by the Chávez and Maduro administrations as Venezuela’s great partner with common interests, co-signatory of more than 500 agreements in the past 20 years, and provider of multimillion-dollar loans that have brought about huge debts to the South American country. -

Lithium Enrichment in the No. 21 Coal of the Hebi No. 6 Mine, Anhe Coalfield, Henan Province, China

minerals Article Lithium Enrichment in the No. 21 Coal of the Hebi No. 6 Mine, Anhe Coalfield, Henan Province, China Yingchun Wei 1,* , Wenbo He 1, Guohong Qin 2, Maohong Fan 3,4 and Daiyong Cao 1 1 State Key Laboratory of Coal Resources and Safe Mining, College of Geoscience and Surveying Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology, Beijing 100083, China; [email protected] (W.H.); [email protected] (D.C.) 2 College of Resources and Environmental Science, Hebei Normal University, Shijiazhuang 050024, China; [email protected] 3 Departments of Chemical and Petroleum Engineering, and School of Energy Resources, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071, USA; [email protected] 4 School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Mason Building, 790 Atlantic Drive, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 May 2020; Accepted: 3 June 2020; Published: 5 June 2020 Abstract: Lithium (Li) is an important strategic resource, and with the increasing demand for Li, there are some limitations in the exploitation and utilization of conventional deposits such as the pegmatite-type and brine-type Li deposits. Therefore, it has become imperative to search for Li from other sources. Li in coal is thought to be one of the candidates. In this study, the petrology, mineralogy, and geochemistry of No. 21 coal from the Hebi No. 6 mine, Anhe Coalfield, China, was reported, with an emphasis on the distribution, modes of occurrence, and origin of Li. The results show that Li is enriched in the No. 21 coal, and its concentration coefficient (CC) value is 6.6 on average in comparison with common world coals. -

Annual Reportreport

(Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock Code: 691 20092009 AnnualAnnual ReportReport Annual Report 2009Annual Report 2009 Headquarter: Sunnsy Industrial Park, Gushan Town, Changqing District, Jinan, Shandong, China Hong Kong Office: Room 2609, 26/F, Tower 2, Lippo Centre, 89 Queensway, Admiralty, Hong Kong Contents DEFINITIONS 2 I COMPANY PROFILE 3 II CORPORATE INFORMATION 6 III FINANCIAL DATA SUMMARY 14 IV CHANGES IN SHARE CAPITAL AND SHAREHOLDINGS OF SUBSTANTIAL SHAREHOLDERS AND THE DIRECTORS 15 V BASIC INFORMATION ON DIRECTORS, SENIOR MANAGEMENT AND EMPLOYEES 22 VI REPORT ON CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 30 VII MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS 38 VIII REPORT OF THE DIRECTORS 51 IX SIGNIFICANT EVENTS 59 X INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT 61 XI FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 63 China Shanshui Cement Group Limited • Annual Report 2009 1 Definitions In this annual report, unless the context otherwise requires, the following words and expressions have the following meanings: “Company” or “Shanshui Cement” China Shanshui Cement Group Limited “Group” or “Shanshui Group” the Company and its subsidiaries “Reporting Period” 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2009 “Directors” Directors of the Company “Board” Board of Directors of the Company “Stock Exchange” The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited “Listing Rules of the Stock Exchange” the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on the Stock Exchange “SFO” Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571) (as amended, supplemented or otherwise modified from time to time) “Hong Kong” Hong Kong Special -

China's Supply-Side Structural Reforms: Progress and Outlook

China’s supply-side structural reforms: Progress and outlook A report by The Economist Intelligence Unit www.eiu.com The world leader in global business intelligence The Economist Intelligence Unit (The EIU) is the research and analysis division of The Economist Group, the sister company to The Economist newspaper. Created in 1946, we have 70 years’ experience in helping businesses, financial firms and governments to understand how the world is changing and how that creates opportunities to be seized and risks to be managed. Given that many of the issues facing the world have an international (if not global) dimension, The EIU is ideally positioned to be commentator, interpreter and forecaster on the phenomenon of globalisation as it gathers pace and impact. EIU subscription services The world’s leading organisations rely on our subscription services for data, analysis and forecasts to keep them informed about what is happening around the world. We specialise in: • Country Analysis: Access to regular, detailed country-specific economic and political forecasts, as well as assessments of the business and regulatory environments in different markets. • Risk Analysis: Our risk services identify actual and potential threats around the world and help our clients understand the implications for their organisations. • Industry Analysis: Five year forecasts, analysis of key themes and news analysis for six key industries in 60 major economies. These forecasts are based on the latest data and in-depth analysis of industry trends. EIU Consulting EIU Consulting is a bespoke service designed to provide solutions specific to our customers’ needs. We specialise in these key sectors: • Consumer Markets: Providing data-driven solutions for consumer-facing industries, we and our management consulting firm, EIU Canback, help clients to enter new markets and be successful in current markets. -

The Program of CHINA MINING 2017

The Program of CHINA MINING 2017 Friday, Sept.22nd, 2017 PM Inaugural Meeting of China Mining International Productivity Cooperation Enterprises Alliance (Banquet Hall, 4th Fl, Crown Plaza Hotel, Tianjin Meijiang Center) Hosted by: China Mining Association Chair: Yu Qinghe, Vice President & Secretary-General , China Mining Association 15:30-16:00 Preliminary Meeting: • Discuss Proposal of “China Mining International Productivity Cooperation Enterprises Alliance” (Draft) • Discuss Regulations of “China Mining International Productivity Cooperation Enterprises Alliance” (Draft) • Discuss Candidate for President, Vice Presidents and Secretary-General of the first Council • Participants: Representatives of Founders and Members of the Alliance Inaugural Meeting: • Announce Approval Document of National Development and Reform Commission • Speech by Leader from MLR 16:00-17:00 • Speech by Leader from International Cooperation Center of National Development and Reform Commission • Speech by Founder Representative--China Minmetals • Address by New Elected President of the Council • Inauguration Ceremony(Leaders from MLR, NDRC, Departments of MLR, China Mining Association) 17:30-20:00 "Night of BOC" (No.6 Building, Tianjin Guest House) (Invitation ONLY) Mining Cooperation Communication Cocktail Party of CHINA MINING 2017(Hosted by China Mining Association)(Banquet Hall, 4th Fl, Crown Plaza Hotel, 17:30-21:00 Tianjin Meijiang Center) 1/9 Saturday, Sept.23rd, 2017 AM 08:30-09:00 Doors open to the delegates Opening Ceremony of CHINA MINING Congress and Expo 2017 (Rm. Conference Hall N7, 1st Fl.) Chair: The Hon. Cao Weixing, Deputy Minister, Ministry of Land and Resources, PRC 09:00-9:50 • The Hon. Jiang Daming, Minister of Land and Resources, PRC • The Hon. Wang Dongfeng, Mayor of Tianjin, PRC • H.E. -

Environmental Impacts of China Outward Foreign Direct Investment

GEORGE BUSH SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT AND PUBLIC SERVICE Environmental Impacts of China Outward Foreign Direct Investment Case Studies in Latin America, Mongolia, Myanmar, and Zambia Nour Al-Aameri, Lingxiao Fu, Nicole Garcia, Ryan Mak, Caitlin McGill, Amanda Reynolds, Lucas Vinze Advisor: Dr. Ren Mu Capstone Project for The Nature Conservancy 2012 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 2 Country Report .................................................................................................................................. 6 Part I: China Overview………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 Part 2: South America ........................................................................................................................... 29 Part 3: Mongolia……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….41 Part 4: Myanmar…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…50 Part 5: Zambia……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………68 Policy Recommendations ................................................................................................................ 85 Part I: Environmental Regulation and FDI Debate…………………………………………………..………………………….86 Part II: Case Study Comparisons of OFDI Environmental Legislation and Challenges…………………………87 Part III: NGO Literature Review…………………………………………………………………………………………………………90 Part IV: Recommendations……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….92 2 Executive Summary China’s -

Sino-Venezuelan Relations: Beyond Oil

Issues & Studies© 44, no. 3 (September 2008): 99-147. Sino-Venezuelan Relations: Beyond Oil JOSEPH Y. S. CHENG AND HUANGAO SHI Sino-Venezuelan relations have witnessed an unprecedented inti- macy since the beginning of Hugo Chávez's presidency in 1999. While scholars hold divergent views on the possible implications of the suddenly improved bilateral relationship, they have reached a basic consensus that oil has been the driving force. This article explores the underlying dy- namics of this relationship from the Chinese perspective. It argues that oil interest actually plays a rather limited role and will continue to remain an insignificant variable in Sino-Venezuelan ties in the foreseeable future. Despite the apparent closeness of the ties in recent years, the foundation forcontinued improvement in the future seems farfromsolid. Sino-Venezue- lan relations have caused serious concerns in the United States, which, for centuries, have seen Latin America as its sphere of influence. Although the neo-conservatives are worried about the deviant Chávez administration and a rising China, the chance of any direct U.S. intervention remains slim. Nevertheless, the China-U.S.-Venezuelan triangular relationship poses a JOSEPH Y. S. CHENG (鄭宇碩) is chair professor of political science and coordinator of the Contemporary China Research Project, City University of Hong Kong. He is the founding editor of the Hong Kong Journal of Social Sciences and The Journal of Comparative Asian Development. He has published widely on political development in China and Hong Kong, Chinese foreign policy, and local government in southern China. His e-mail address is <[email protected]>. -

The China Analyst 中国分析家 a Knowledge Tool by the Beijing Axis for Executives with a China Agenda March 2011

The China Analyst 中国分析家 A knowledge tool by The Beijing Axis for executives with a China agenda March 2011 Doing Business in a Fast Changing China Features China in 2030: Outlines of a Chinese Future 6 China’s Construction Industry: Strategic Options for Foreign Players 9 Gearing Up: Engaging China’s Globalising Machinery Industry 12 Clean Coal: China’s Coming Revolution 15 Regulars China Sourcing Strategy 26 China Capital: Inbound/Outbound FDI & Financial Markets 30 Strategy: China Shenhua 34 Regional Focus: China-Africa 39 Regional Focus: China-Australia 44 Regional Focus: China-Latin America 48 Regional Focus: China-Russia 52 The Westward Shift of Growth in China* Five Largest Provincial GDP, USD, Q3 2010 Five Fastest Growing Provincial GDP, % y-o-y, Q3 2010 Guangdong - USD 473.6 bn Tianjin - 17.9% Jiangsu - USD 440.7 bn Hainan - 17.6% Shandong - USD 424.3 bn Chongqing - 17.1% Zhejiang - USD 281.7 bn Shanxi - 15.7% Henan - USD 254.3 bn Ningxia - 15.5% Five Highest Provincial Five Fastest Growing Provincial Average Urban Wages, USD, Q3 20101 Average Urban Wages, % y-o-y, Q3 20102 Beijing - USD 6,845 Shanghai - USD 6,777 Tibet - USD 5,287 Tianjin - USD 5,021 Guangdong - USD 4,281 Hainan - 20.6% Ningxia - 19.6% Xinjiang - 19.4% Gansu - 16.7% Sichuan - 16.0% Five Highest Provincial Total Profits of Five Fastest Growing Provincial Total Profits Industrial Enterprises, USD, Jan-Nov 2010 of Industrial Enterprises, % y-o-y, Jan-Nov 2010 Shandong - USD 81.1 bn Shanxi - 124.6% Jiangsu - USD 71.1 bn -

Human Impact Overwhelms Long-Term Climate Control of Weathering and Erosion in Southwest China

1 Geology Achimer June 2015, Volume 43 Issue 5 Pages 439-442 http://dx.doi.org/10.1130/G36570.1 http://archimer.ifremer.fr http://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00266/37754/ © 2015 Geological Society of America. For permission to copy, contact [email protected]. Human impact overwhelms long-term climate control of weathering and erosion in southwest China Wan S. 1, *, Toucanne Samuel 2, Clift P. D. 3, Zhao D. 1, Bayon Germain 2, 4, Yu Z. 5, Cai G. 6, Yin Xiaoming 1, Revillon Sidonie 7, Wang D. 1, Li A. 1, Li T. 1 1 Key Laboratory of Marine Geology and Environment, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China 2 IFREMER, Unité de Recherche Géosciences Marines, BP70, 29280 Plouzané, France 3 Department of Geology and Geophysics, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803, USA 4 Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Museum for Central Africa, B-3080 Tervuren, Belgium 5 Laboratoire IDES, UMR 8148 CNRS, Université de Paris XI, Orsay 91405, France 6 Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey, Guangzhou 510760, China 7 SEDISOR/UMR 6538 “Domaines Oceaniques”, IUEM, Place Nicolas Copernic, 29280 Plouzané, France Abstract : During the Holocene there has been a gradual increase in the influence of humans on Earth systems. High-resolution sedimentary records can help us to assess how erosion and weathering have evolved in response to recent climatic and anthropogenic disturbances. Here we present data from a high- resolution (∼75 cm/k.y.) sedimentary archive from the South China Sea. Provenance data indicate that the sediment was derived from the Red River, and can be used to reconstruct the erosion and/or weathering history in this river basin. -

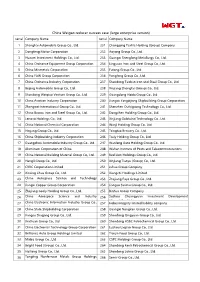

China Weigao Reducer Success Case (Large Enterprise Version) Serial Company Name Serial Company Name

China Weigao reducer success case (large enterprise version) serial Company Name serial Company Name 1 Shanghai Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 231 Chongqing Textile Holding (Group) Company 2 Dongfeng Motor Corporation 232 Aoyang Group Co., Ltd. 3 Huawei Investment Holdings Co., Ltd. 233 Guangxi Shenglong Metallurgy Co., Ltd. 4 China Ordnance Equipment Group Corporation 234 Lingyuan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 5 China Minmetals Corporation 235 Futong Group Co., Ltd. 6 China FAW Group Corporation 236 Yongfeng Group Co., Ltd. 7 China Ordnance Industry Corporation 237 Shandong Taishan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 8 Beijing Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 238 Xinjiang Zhongtai (Group) Co., Ltd. 9 Shandong Weiqiao Venture Group Co., Ltd. 239 Guangdong Haida Group Co., Ltd. 10 China Aviation Industry Corporation 240 Jiangsu Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Group Corporation 11 Zhengwei International Group Co., Ltd. 241 Shenzhen Oufeiguang Technology Co., Ltd. 12 China Baowu Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 242 Dongchen Holding Group Co., Ltd. 13 Lenovo Holdings Co., Ltd. 243 Xinjiang Goldwind Technology Co., Ltd. 14 China National Chemical Corporation 244 Wanji Holding Group Co., Ltd. 15 Hegang Group Co., Ltd. 245 Tsingtao Brewery Co., Ltd. 16 China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation 246 Tasly Holding Group Co., Ltd. 17 Guangzhou Automobile Industry Group Co., Ltd. 247 Wanfeng Auto Holding Group Co., Ltd. 18 Aluminum Corporation of China 248 Wuhan Institute of Posts and Telecommunications 19 China National Building Material Group Co., Ltd. 249 Red Lion Holdings Group Co., Ltd. 20 Hengli Group Co., Ltd. 250 Xinjiang Tianye (Group) Co., Ltd. 21 CRRC Corporation Limited 251 Juhua Group Company 22 Xinxing Jihua Group Co., Ltd. -

EXHIBITOR PROSPECTUS Minexpo INTERNATIONAL® Is the World’S Largest and Most Comprehensive Global Mining Event

ALL THE RESOURCES YOU NEED SPONSORED BY EXHIBITOR PROSPECTUS MINExpo INTERNATIONAL® is the world’s largest and most comprehensive global mining event. In just three days—and in one place—you’ll meet thousands of people in mining with the buying power and influence to purchase the equipment, products and services you bring to the show. Nothing beats the in-person experiences, meetings and networking that will take place in September 2021. OUR COMMITMENT TO YOUR SAFETY Your health and safety is our top priority. We are committed to following the guidance of the CDC, state and local authorities as well as the Las Vegas Convention Center, a Global Biorisk Advisory Council Star facility. Below are a few of the safety protocols you can expect at MINExpo®: REMOVE THIS PAGE • Easily-accessible hand-washing and/or sanitizing systems • Strict enforcement of mask and social distancing mandates • Rigorous employee training to uphold preventative measures and reporting functions FROM EXPORTED PDF • Effective use of approved disinfectants and delivery systems • Rapid response protocols for skilled health and safety professionals For more information or to reserve your booth, visit www.minexpo.com. BUYERS ARE READY Ready To Buy The numbers don’t lie: With $7.3 million spent at MINExpo on average, attendees are ready to purchase. You can drill into the figures any way you want—every segment of the mining industry is at the show. This is a rare opportunity for manufacturers and suppliers to reach thousands of domestic and international buyers with the purchasing power and motivation to make buying decisions on-site. -

The History and Economics of Gold Mining in China

Ore Geology Reviews 65 (2015) 718–727 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ore Geology Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/oregeorev The history and economics of gold mining in China Rui Zhang, Huayan Pian ⁎, M. Santosh, Shouting Zhang School of Earth Sciences and Resources, China University of Geosciences Beijing, 29 Xueyuan Road, Beijing 100083, China article info abstract Article history: As the largest producer of gold in the world, China's gold reserves are spread across a number of orogenic belts Received 23 January 2014 that were constructed around ancient craton margins during various subduction–collision cycles, as well as with- Received in revised form 4 March 2014 in the cratonic interior along reactivated paleo-sutures. Among the major gold deposits in China is the unique Accepted 5 March 2014 class of world's richest gold mines in the Jiaodong Peninsula in the eastern part of the North China Craton with Available online 20 March 2014 an overall endowment of N3000 tons. Following the dawn of metal in the third millennium BC in western Keywords: China, placer gold mining was soon in practice, particularly during the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties. During Gold deposits 1096 AD, mining techniques were developed to dig underground tunnels and the earliest mineral processing Geology technology was in place to pan gold from crushed rock ores. However, ancient China did not witness any History major breakthrough in gold exploitation and production, and the growth in the gold ownership was partly due Economics to the ‘Silk Road’ that enabled the sale of silk products and exquisite artifacts to the west in exchange of gold prod- China ucts.