Title Anthophilous Insect Community and Plant-Pollinator Interactions On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safe Movement of Small Fruit Germplasm

FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION INTERNATIONAL PLANT OF THE UNITED NATIONS GENETIC RESOURCES INSTITUTE FAO/IPGRI TECHNICAL GUIDELINES FOR THE SAFE MOVEMENT OF SMALL FRUIT GERMPLASM Edited by M. Diekmann, E.A. Frison and T. Putter In collaboration with the Small Fruit Virus Working Group of the International Society for Horticultural Science 2 CONTENTS Introduction 4 2.Strawberrygreenpetal 31 3. Witches-broom and multiplier Contributors 6 disease 33 Prokaryoticdiseases-bacteria 35 General Recommendations 8 1.Strawberryangular leaf spot 35 2.Strawberrybacterialwilt 36 Technical Recommendations 8 3. Marginal chlorosis of strawberry 37 A. Pollen 8 Fungal diseases 38 B. Seed 9 1. Alternaria leaf spot 38 C. In vitro material 9 2 Anthracnose 39 D. Vegetative propagules 9 3. Fusarium wilt 40 E. Disease indexing 10 4.Phytophthoracrownrot 41 F. Therapy 11 5.Strawberry black root rot 42 6. Strawberry red stele (red core) 43 Descriptions of Pests 13 7. Verticillium wilt 44 Fragaria spp. (strawberry) 13 Ribesspp.(currant,gooseberry) 45 Viruses 13 Viruses 45 1. Ilarviruses 13 1.Alfalfamosaicvirus(AMV) 45 2. Nepoviruses 14 2. Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) 46 3. Pallidosis 15 3. Gooseberry vein banding virus 4. Strawberry crinkle virus (SCrV) 17 (GVBV) 48 5. Strawberry latent C virus (SLCV) 18 4. Nepoviruses 50 6.Strawberry mildyellow-edge 19 5.Tobacco rattlevirus(TRV) 51 7. Strawberry mottle virus (SMoV) 21 Diseasesofunknownetiology 53 8. Strawberry pseudo mild 1. Black currant yellows 53 yellow-edgevirus(SPMYEV) 22 2. Reversion of red and black currant 54 9. Strawberry vein banding 3.Wildfireof blackcurrant 56 virus (SVBV) 23 4.Yellow leaf spotofcurrant 57 Diseasesofunknownetiology 25 Prokaryotic disease 58 1. -

Final Report Template

Native Legumes as a Grain Crop for Diversification in Australia RIRDC Publication No. 10/223 RIRDCInnovation for rural Australia Native Legumes as a Grain Crop for Diversification in Australia by Megan Ryan, Lindsay Bell, Richard Bennett, Margaret Collins and Heather Clarke October 2011 RIRDC Publication No. 10/223 RIRDC Project No. PRJ-000356 © 2011 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-188-4 ISSN 1440-6845 Native Legumes as a Grain Crop for Diversification in Australia Publication No. 10/223 Project No. PRJ-000356 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. -

Phylogeny and Classification of the Melastomataceae and Memecylaceae

Nord. J. Bot. - Section of tropical taxonomy Phylogeny and classification of the Melastomataceae and Memecy laceae Susanne S. Renner Renner, S. S. 1993. Phylogeny and classification of the Melastomataceae and Memecy- laceae. - Nord. J. Bot. 13: 519-540. Copenhagen. ISSN 0107-055X. A systematic analysis of the Melastomataceae, a pantropical family of about 4200- 4500 species in c. 166 genera, and their traditional allies, the Memecylaceae, with c. 430 species in six genera, suggests a phylogeny in which there are two major lineages in the Melastomataceae and a clearly distinct Memecylaceae. Melastomataceae have close affinities with Crypteroniaceae and Lythraceae, while Memecylaceae seem closer to Myrtaceae, all of which were considered as possible outgroups, but sister group relationships in this plexus could not be resolved. Based on an analysis of all morph- ological and anatomical characters useful for higher level grouping in the Melastoma- taceae and Memecylaceae a cladistic analysis of the evolutionary relationships of the tribes of the Melastomataceae was performed, employing part of the ingroup as outgroup. Using 7 of the 21 characters scored for all genera, the maximum parsimony program PAUP in an exhaustive search found four 8-step trees with a consistency index of 0.86. Because of the limited number of characters used and the uncertain monophyly of some of the tribes, however, all presented phylogenetic hypotheses are weak. A synapomorphy of the Memecylaceae is the presence of a dorsal terpenoid-producing connective gland, a synapomorphy of the Melastomataceae is the perfectly acrodro- mous leaf venation. Within the Melastomataceae, a basal monophyletic group consists of the Kibessioideae (Prernandra) characterized by fiber tracheids, radially and axially included phloem, and median-parietal placentation (placentas along the mid-veins of the locule walls). -

Pyrethrum, Coltsfoot and Dandelion: Important Medicinal Plants from Asteraceae Family

Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 5(12): 1787-1791, 2011 ISSN 1991-8178 Pyrethrum, Coltsfoot and Dandelion: Important Medicinal Plants from Asteraceae Family Shahram Sharafzadeh Department of Agriculture, Firoozabad Branch, Islamic Azad University, Firoozabad, Iran Abstract: Medicinal plants synthesize substances that are useful to the maintenance of health in humans and animals. Asteraceae (Compositae) is one of the largest families contains very useful pharmaceutical genera such as chrysanthemum, Tussilago and Taraxacum. Pyrethrum is under cultivation around the world and is known for its insecticidal activity. Coltsfoot is a perennial plant. The extracts of coltsfoot exhibit antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. Dandelion is almost stemless and a perennial herb. This plant is a good indicator of environmental pollution. Dandelion has shown anti-inflammatory activity and the aqueous extract seems to have anti-tumour activity. The objective of this study was review of researches regarding to these plants and their secondary metabolites. Key words: Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium, Tussilago farfara, Taraxacum officinale, secondary metabolites, compositae. INTRODUCTION Medicinal and aromatic plants use by 80% of global population for their medicinal therapeutic effects as reported by WHO (2008). Many of these plants synthesize substances that are useful to the maintenance of health in humans and other animals. These include aromatic substances, most of which are phenols or their oxygen-substituted derivatives such as tannins. Others contain alkaloids, glycosides, saponins, and many secondary metabolites (Naguib, 2011). Asteraceae (Compositae) is one of the largest families of vascular plants represented by 22750 species and over 1528 genera all over the world (Bremer, 1994). This family contains very useful pharmaceutical genera such as chrysanthemum, Tussilago and Taraxacum (Hadaruga, et al., 2009). -

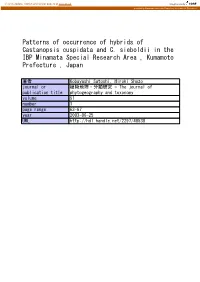

Patterns of Occurrence of Hybrids of Castanopsis Cuspidata and C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kanazawa University Repository for Academic Resources Patterns of occurrence of hybrids of Castanopsis cuspidata and C. sieboldii in the IBP Minamata Special Research Area , Kumamoto Prefecture , Japan 著者 Kobayashi Satoshi, Hiroki Shozo journal or 植物地理・分類研究 = The journal of publication title phytogeography and toxonomy volume 51 number 1 page range 63-67 year 2003-06-25 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2297/48538 Journal of Phytogeography and Taxonomy 51 : 63-67, 2003 !The Society for the Study of Phytogeography and Taxonomy 2003 Satoshi Kobayashi and Shozo Hiroki : Patterns of occurrence of hybrids of Castanopsis cuspidata and C. sieboldii in the IBP Minamata Special Research Area , Kumamoto Prefecture , Japan Graduate School of Human Informatics, Nagoya University, Chikusa-Ku, Nagoya 464―8601, Japan Castanopsis cuspidata(Thunb.)Schottky and However, it is difficult to identify the hybrids by C. sieboldii(Makino)Hatus. ex T. Yamaz. et nut morphology alone, because the nut shapes of Mashiba are dominant components of the ever- the 2 species are variable and can overlap with green broad-leaved forests of southwestern Ja- each other. Kobayashi et al.(1998)showed that pan, including parts of Honshu, Kyushu and hybrids have a chimeric structure of both 1 and Shikoku but excluding the Ryukyu Islands(Hat- 2 epidermal layers within a leaf. These morpho- tori and Nakanishi 1983).Although these 2 Cas- logical differences among C. cuspidata, C. sie- tanopsis species are both climax species, it is boldii and their hybrid can be confirmed by ge- very difficult to distinguish them because of the netic differences in nuclear species-specific existence of an intermediate type(hybrid). -

Phylogeny of the Genus Lotus (Leguminosae, Loteae): Evidence from Nrits Sequences and Morphology

813 Phylogeny of the genus Lotus (Leguminosae, Loteae): evidence from nrITS sequences and morphology G.V. Degtjareva, T.E. Kramina, D.D. Sokoloff, T.H. Samigullin, C.M. Valiejo-Roman, and A.S. Antonov Abstract: Lotus (120–130 species) is the largest genus of the tribe Loteae. The taxonomy of Lotus is complicated, and a comprehensive taxonomic revision of the genus is needed. We have conducted phylogenetic analyses of Lotus based on nrITS data alone and combined with data on 46 morphological characters. Eighty-one ingroup nrITS accessions represent- ing 71 Lotus species are studied; among them 47 accessions representing 40 species are new. Representatives of all other genera of the tribe Loteae are included in the outgroup (for three genera, nrITS sequences are published for the first time). Forty-two of 71 ingroup species were not included in previous morphological phylogenetic studies. The most important conclusions of the present study are (1) addition of morphological data to the nrITS matrix produces a better resolved phy- logeny of Lotus; (2) previous findings that Dorycnium and Tetragonolobus cannot be separated from Lotus at the generic level are well supported; (3) Lotus creticus should be placed in section Pedrosia rather than in section Lotea; (4) a broad treatment of section Ononidium is unnatural and the section should possibly not be recognized at all; (5) section Heineke- nia is paraphyletic; (6) section Lotus should include Lotus conimbricensis; then the section is monophyletic; (7) a basic chromosome number of x = 6 is an important synapomorphy for the expanded section Lotus; (8) the segregation of Lotus schimperi and allies into section Chamaelotus is well supported; (9) there is an apparent functional correlation be- tween stylodium and keel evolution in Lotus. -

Full Article

Phytotaxa 233 (1): 027–048 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.233.1.2 Taxonomy and phylogeny of Cercospora spp. from Northern Thailand JEERAPA NGUANHOM1, RATCHADAWAN CHEEWANGKOON1, JOHANNES Z. GROENEWALD2, UWE BRAUN3, CHAIWAT TO-ANUN1* & PEDRO W. CROUS2,4 1Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture, Chiang Mai University, 50200, Thailand *email: [email protected] 2CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Uppsalalaan 8, 3584 CT Utrecht, The Netherlands 3Martin-Luther-Universität, Institut für Biologie, Bereich Geobotanik und Botanischer Garten, Herbarium, Neuwerk 21, 06099 Halle (Saale), Germany 4Department of Microbiology and Plant Pathology, Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa Abstract The genus Cercospora represents a group of important plant pathogenic fungi with a wide geographic distribution, being commonly associated with leaf spots on a broad range of plant hosts. The goal of the present study was to conduct a mor- phological and molecular phylogenetic analysis of the Cercospora spp. occurring on various plants growing in Northern Thailand, an area with a tropical savannah climate, and a rich diversity of vascular plants. Sixty Cercospora isolates were collected from 29 host species (representing 16 plant families). Partial nucleotide sequence data for two gene loci (ITS and cmdA), were generated for all isolates. Results from this study indicate that members of the genus Cercospora vary regarding host specificity, with some taxa having wide host ranges, and others being host-specific. Based on cultural, morphological and phylogenetic data, four new species of Cercospora could be identified: C. -

Patterns of Flammability Across the Vascular Plant Phylogeny, with Special Emphasis on the Genus Dracophyllum

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Patterns of flammability across the vascular plant phylogeny, with special emphasis on the genus Dracophyllum A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy at Lincoln University by Xinglei Cui Lincoln University 2020 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy. Abstract Patterns of flammability across the vascular plant phylogeny, with special emphasis on the genus Dracophyllum by Xinglei Cui Fire has been part of the environment for the entire history of terrestrial plants and is a common disturbance agent in many ecosystems across the world. Fire has a significant role in influencing the structure, pattern and function of many ecosystems. Plant flammability, which is the ability of a plant to burn and sustain a flame, is an important driver of fire in terrestrial ecosystems and thus has a fundamental role in ecosystem dynamics and species evolution. However, the factors that have influenced the evolution of flammability remain unclear. -

Post-Fire Recovery of Woody Plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion

Post-fire recovery of woody plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion Peter J. ClarkeA, Kirsten J. E. Knox, Monica L. Campbell and Lachlan M. Copeland Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Sciences, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, AUSTRALIA. ACorresponding author; email: [email protected] Abstract: The resprouting response of plant species to fire is a key life history trait that has profound effects on post-fire population dynamics and community composition. This study documents the post-fire response (resprouting and maturation times) of woody species in six contrasting formations in the New England Tableland Bioregion of eastern Australia. Rainforest had the highest proportion of resprouting woody taxa and rocky outcrops had the lowest. Surprisingly, no significant difference in the median maturation length was found among habitats, but the communities varied in the range of maturation times. Within these communities, seedlings of species killed by fire, mature faster than seedlings of species that resprout. The slowest maturing species were those that have canopy held seed banks and were killed by fire, and these were used as indicator species to examine fire immaturity risk. Finally, we examine whether current fire management immaturity thresholds appear to be appropriate for these communities and find they need to be amended. Cunninghamia (2009) 11(2): 221–239 Introduction Maturation times of new recruits for those plants killed by fire is also a critical biological variable in the context of fire Fire is a pervasive ecological factor that influences the regimes because this time sets the lower limit for fire intervals evolution, distribution and abundance of woody plants that can cause local population decline or extirpation (Keith (Whelan 1995; Bond & van Wilgen 1996; Bradstock et al. -

Camellia Sinensis (L.) Kuntze (7)

“As Primeiras Camélias Asiáticas a Chegarem a Portugal e à Europa”. Armando Oliveira António Sanches (1623), Planisfério. 1 O género Camellia L. está praticamente confinado ao sul da China (80% de todas as espécies) e à região do sul da Ásia que inclui as Filipinas e as zonas do noroeste do arquipélago da Indonésia, com a inclusão do Japão e partes da Coreia. Estima-se que praticamente 20% das espécies de Camellia se encontram no Vietname. A região fitogeográfica do sul da Ásia é composta pela China, Laos, Mianmar (ex-Birmânia), Tailândia, Camboja e Vietname. 1 (Huang et al., 2016) 106 • A proposta taxonómica de Linnaeus (1835), “Sistema Natura”, permitiu-nos obter uma mais fácil e rápida identificação das espécies. • Baseia-se numa classificação dita binomial que atribui nomes compostos por duas palavras, quase sempre recorrendo ao latim. Adaptado de Fairy Lake Botanical Garden Flora (2018) 2 Reino Filo Classe Ordem Família Género Espécies/Variedades Cultivares Camellia caudata Wall. (11) Camellia drupifera Lour. (4) Dicotiledóneas Antófitas Camellia euryoides Lindl. (7) Vegetal (a semente Ericales (25) Theaceaes (12) Camellia (102+40) (que dão flor) contém 2 ou mais Camellia japonica L. cotilédones) Camellia kissi Wall. (11) Camellia oleifera Abel (6) Camellia rosaeflora Hook. (1) Camellia sasanqua Thunb. Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze (7) • A 1ª parte do nome é referente ao género da espécie em causa e a 2ª parte identifica a espécie dentro de um determinado género. Adaptado de Fairy Lake Botanical Garden Flora (2018) 2 Ordem Família -

International Camellia Journal 2017

International Camellia Journal 2017 An official publication of the International Camellia Society Journal Number 49 ISSN 0159-656X International Camellia Journal 2017 No. 49 International Camellia Society Congress 2018 Nantes, France, March 25 to 29 Pre-Congress Tour March 21-25 Gardens in Brittany Aims of the International Camellia Society Congress Registration March 25 in Nantes To foster the love of camellias throughout the world and maintain and increase their popularity Post-Congress Tours To undertake historical, scientific and horticultural research in connection with camellias Tour A March 29 to 31 Normandy, including World War II To co-operate with all national and regional camellia societies and with other horticultural societies sites To disseminate information concerning camellias by means of bulletins and other publications To encourage a friendly exchange between camellia enthusiasts of all nationalities Tour B March 29 to 31 Gardens and nurseries in southwest France Major dates in the International Camellia Society calendar Reassemble in Paris April 1 to 2, including visit to Versailles International Camellia Society Congresses 2018 - Nantes, Brittany, France. 2020 - Goto City, Japan. 2022 - Italy ISSN 0159-656X Published in 2017 by the International Camellia Society. © The International Camellia Society unless otherwise stated 3 Contents Camellia research A transcriptomic database of petal blight-resistant Camellia lutchuensis 47 Nikolai Kondratev1, Matthew Denton-Giles1,2, Cade D Fulton1, President’s message 6 Paul P Dijkwel1 -

Litterfall Dynamics After a Typhoon Disturbance in a Castanopsis Cuspidata Coppice, Southwestern Japan Tamotsu Sato

Litterfall dynamics after a typhoon disturbance in a Castanopsis cuspidata coppice, southwestern Japan Tamotsu Sato To cite this version: Tamotsu Sato. Litterfall dynamics after a typhoon disturbance in a Castanopsis cuspidata coppice, southwestern Japan. Annals of Forest Science, Springer Nature (since 2011)/EDP Science (until 2010), 2004, 61 (5), pp.431-438. 10.1051/forest:2004036. hal-00883773 HAL Id: hal-00883773 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00883773 Submitted on 1 Jan 2004 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ann. For. Sci. 61 (2004) 431–438 431 © INRA, EDP Sciences, 2004 DOI: 10.1051/forest:2004036 Original article Litterfall dynamics after a typhoon disturbance in a Castanopsis cuspidata coppice, southwestern Japan Tamotsu SATOa,b* a Kyushu Research Center, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute (FFPRI), 4-11-16 Kurokami, Kumamoto, Kumamoto 860-0862, Japan b Present address: Department of Forest Vegetation, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute (FFPRI), PO Box 16, Tsukuba Norin, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8687, Japan (Received 11 April 2003; accepted 3 September 2003) Abstract – Litterfall was measured for eight years (1991–1998) in a Castanopsis cuspidata coppice forest in southwestern Japan.