RC Supplement-1948 Vol-1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revue Internationale De La Croix-Rouge Et Bulletin Des Societes De La Croix-Rouge

REVUE INTERNATIONALE DE LA CROIX-ROUGE ET BULLETIN DES SOCIETES DE LA CROIX-ROUGE SUPPLEMENT First Year, I948 GENEVE 1948 SUPPLEMENT VOL. I REVUE INTERNATIONALE DE LA CROIX-ROUGE ET BULLETIN DES SOCIETES DE LA CROIX-ROUGE SUPPLEMENT March,1948 NO·3 CONTENTS Page Mission of the International Committee in Palestine . .. 42 Mission of the International Committee to the United States and to Canada . 43 The Far Eastern Conflict (Part I) 45 Published by Comite international de la Croix-Rouge, Geueve Editor: Louis Demolis MISSION OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE IN PALESTINE In pursuance of a request made by the Government of the mandatory Power in Palestine, the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva, who had previously been authorized to visit the camps of persons detained in consequence of recent events, have despatched a special mission to Palestine. This . mission has been instructed to study, in co-operation with all parties, the problems arising from the humanitarian work which appears to be indispensable in view of the present situation. The Committee's delegates have met on all hands with a most frie~dly reception. During the last few weeks, they have had talks with the Government Authorities and the Arab and Jewish representatives; they have offered to all concerned the customary services of the Committee as a neutral intermediary, having in mind especially the protection and care of wounded, sick and prisoners. During their tour of the country the Committee's delegates visited a large number of hospitals and refugee camps, and collected information on the present needs in hospital staff, doctors and nurses, as well as in ambulances and medical supplies. -

Reproachless Heroes of World War 11: a Cinematic Approach Through Two American Movies

~ S T 0 + • .; ~ .,.. Volume m Number 1-2 1993 o.l .. .......... 9' REPROACHLESS HEROES OF WORLD WAR 11: A CINEMATIC APPROACH THROUGH TWO AMERICAN MOVIES CHRISTINE S. DILIGENTI-GA VRILINE Lycee Ozar Hatorah, Toulouse As a manly universe, war is above all a soldierly one, the one of fighting armies. Cinema does not derogate to the tradition of representing troops, resting or acting, clean and fresh on the eve of the battle, mud bespattered and devastated afterwards. Looks do not interest us much, even though the circular travellings in Tora! Tora! 'J'ora! for instance, let us admire or appreciate the fine presence of the uniforms: the masterful first images of the film when the entire Japanese Navy, in #1 Ceremonial, greets her new chief-commander, Admiral Yamamoto. The army at wartime still is a particular sphere in the bosom of the State, if she doesn't purely serve as a substitute for it The army is submitted to law and statutes (discipline), obeys to a hierarchy (ranks) that we can, why not. compare to the common social ladder, even if it is not inevitably the social origin that makes the gold braid. The major interest of the classical war cinema is to show soldiers and the army at their best They are the symbol of the unity of the nation against the dangerous enemy that they must fight It is their mission to defeat him. There are numerous movies reflecting this point of view. The American film industry has long been lavish on this subject with movies where John Wayne assumes the part of the hero. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 436 445 SO 030 794 TITLE China: Tradition and Transformation, Curriculum Projects. Fulbright Hays Summer Seminars Abroad 1998 (China). INSTITUTION National Committee on United States-China Relations, New York, NY. SPONS AGENCY Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 393p.; Some pages will not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Asian History; *Chinese Culture; Communism; *Cultural Context; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Learning Activities; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Student Educational Objectives; *Study Abroad IDENTIFIERS *China; Chinese Art; Chinese Civilization; Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; Japan ABSTRACT The curriculum projects in this collection focus on diverse aspects of China, the most populous nation on the planet. The 16 projects in the collection are:(1) "Proposed Secondary Education Asian Social Studies Course with an Emphasis on China" (Jose Manuel Alvarino); (2) "Education in China: Tradition and Transition" (Sue Babcock); (3)"Chinese Art & Architecture" (Sharon Beachum); (4) "In Pursuit of the Color Green: Chinese Women Artists in Transition" (Jeanne Brubaker); (5)"A Host of Ghosts: Dealing with the Dead in Chinese Culture" (Clifton D. Bryant); (6) "Comparative Economic Systems: China and Japan" (Arifeen M. Daneshyar); (7) "Chinese, Japanese, and American Perspectives as Reflected in Standard High School Texts" (Paul Dickler); (8) "Gender Issues in Transitional China" (Jana Eaton); (9) "A Walking Tour of Stone Village: Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics" (Ted Erskin); (10) "The Changing Role of Women in Chinese Society" (John Hackenburg); (11) "Healing Practices: Writing Chinese Culture(s) on the Body: Confirming Identity, Creating Identity" (Sondra Leftoff); (12) "Unit on Modern China" (Thomas J. -

Perfidious Albion Game Index

Perfidious Albion Game Index Currently incorporates issues 21-24, 61-104 Rev Review Srev short review (1 paragraph-1page, may not have separate title) Sr short remarks (1 sentence-1paragraph) Pla Play analysis, replay Disc Discussion Hr House rules, fixes (not in 62,70) Var Variant Scen Scenario Udd upcoming design discussion Err errata Fyno For your nostrils only Mbr Magazine & Book Review section Mbp My Back Pages section Wtps What the players say, from #83 Clio Clio nomination, #86, #87. +..nominated for best, -…nominated for worst historical game (left out for now) Obsb Open the box, stake the bunny! Only games with comments on gameplay are indexed, no announcements of publication or arrival or component listings. However, design discussion and remarks indicative of some sort of evaluation will be included. No guarantees for accuracy or completeness. Note that in particular Sr and Srev entries may not have a separate title and you may have to look for them in the magazine. 1st Cavalry 1964 (Vae Victis) 102 (srev/obsb) 5th Fleet 74 (rev), 75 (sr/fyno) 7 Ages 63 (udd/fyno) 7th Fleet 66 (rev) 8th Army (Attactix) 103 (rev) 13: The Colonies in Revolt 61 (rev), 63 (disc/fyno) The ’45 92 (rev) 1630something 91 (srev/wtps) 1812 (Columbia) 93 (sr) 1807: The Eagle Goes East 90 (fyno), 93 (srev,pla) 1815 79 (rev) 1862 76 (rev) 79 (sr/fyno) 1904/05 102 (rev) 1914: Glory’s End 88 (srev), 90 (srev) 1914: Opening Moves 104 (srev/obsb) 1918: Storm in the West 81/82 (rev), 83 (srev), 84 (sr) Across Five Aprils 84 (wtps,srev), 85 (rev/hr), 86 (sr, -

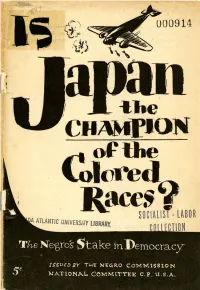

Chamrjon I"' Oftle

= 1 I '5 ~ 000914 .heI CHAMrJON I"' _oftLe ~1(Jred Races? AATLANTJC UNiV ERSJTY lIBRARI: SOC IA1I ST- lAB 0R nON THIS PAMPHLET, issued by the Negro Commission of the National Committee of the Communist Party, U.S.A., was prepared in collaboration by the following outstanding Negro Communists: . THEODORE BASSETT A. W. BERRY CYRIL BRIGGS JAMES W. FORD HARRY HAYWOOD PUBLISHED BY WORKERS LIBRARY PUBLISHERS, INC. P. O. BOX 148, STATION D, NEW YORK, N. Y. AUGUST, 1938 ~209 PRINTED IN THE U.S .A. Contents Introduction 5 I. J ap an's R eal Aims in Asia 7 II. Behind the Scenes in Japan 1 1 III. R ome-Berlin-T okyo Ax is an d the R ace Myth 17 IV. Japan and the Soviet Union-Two Policies Toward China. 21 V. The R eal Liberators of China 24 VI. The Enemy Is Fascism 26 VII. Dem ocra cy and the Colonial Peoples 32 VIII. The Negro's Stake in Democracy 4 1 Introduction aDAy the "Good Earth" .of China is drenched with the T blood and tears of millions of its women and children. Age-old monuments and institutions, representing five thou sand years' contribution to world culture, face destruction. Once flourishing towns and villages lie in ruins. This is the scene behind the lines of the advancing armies of Japanese conquest. Peace-loving humanity the world over stands aghast at this, the latest crime of the Japanese war lords against a peaceful nation. But the deepest disillusionment is felt by the millions of colored peoples in America, Africa and Asia who once re garded seriously japan's claim to leadership of the colored world. -

Final Kietlinski

REVIEW ESSAY The Olympic Games: Showcases of Internationalism and Modernity in Asia Robin Kietlinski, City University of New York – LaGuardia Community College Stefan Huebner. Pan-Asian Sports and the Emergence of Modern Asia, 1913–1974. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2016. 416 pp. $42 (paper). Jessamyn R. Abel. The International Minimum: Creativity and Contradiction in Japan’s Global Engagement, 1933–1964. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2015. 344 pp. $54 (cloth). Over the past two decades, the English-language scholarship on sports in Asia has blossomed. Spurred in part by the announcement in 2001 that Beijing would host the 2008 Summer Olympics, the number of academic symposia, edited volumes, and monographs looking at sports in East Asia from multiple disciplinary perspectives has increased substantially in the twenty- first century. With three Olympic Games forthcoming in East Asia (Pyeongchang 2018, Tokyo 2020, and Beijing 2022), the volume of scholarship on sports, the Olympics, and body culture in this region has continued to grow and to become ever more nuanced. Prior to 2001, very little English-language scholarly work on sports in Asia considered the broader significance of sporting events in East Asian history, societies, and politics (both regional and global). Several recent publications have complicated and contextualized this area of inquiry.1 While some of this recent scholarship makes reference to countries across East Asia, single-author monographs tend to focus on one nation, and particularly on how nationalism and sports fueled each other in the tumultuous twentieth century.2 Scholarship on internationalism in the context of sporting events in East Asia is much harder to come by. -

Contents Perspectives in History Vol

Contents Perspectives in History Vol. XXVIII, 2012-2013 ARTICLES 2 Foreward 3 Crime and Industrialization: A Historical Analysis of Britain’s Penal System Jonathan Hess 11 Chinese Foreign Relations: Economic Imperialism in Imperial and Modern China Anthony Baker 20 Christianity and Education in Kentucky Teri Horsley 26 Rich and Generous: The Story of Two Irish-American Distillers in Northern Kentucky Jake Powers 41 The De Facto Embargo of Japan: An Analysis Zack Bolog 46 An Assessment of Union Victory in the American Civil War Andrew Shepherd REVIEWS 57 Hunting and Foraging in the Eysai Basin A Review by Shane Wagner 60 1492: The Year Our World Began A Review by Aaron Sprinkles 62 The History of Africa: The Quest for Eternal Harmony A Review by Bradford Hogue 63 Nazi Germany and the Jews: 1933-1945 A Review by Clayton Carlisle 1 Foreward Reflecting on my decision to run for Editor-in-Chief of Perspectives, I can’t say I didn’t know what I was getting myself into. As a long-time member of the Alpha Beta Phi Chapter, I have witnessed editors struggle over the years with the monumental task of producing quality examples of academic publishing. For my part, the decision to run for the position of editor was motivated by a simple love of history – and of the expression our authors give to it. For history to be valuable, for it to be more than an antiquarian exercise, it must be kept at the forefront of the collective mind. My hope is that this journal will contribute, in a small but significant way, to the great task of keeping history alive in each successive generation. -

University Microfilms, Inc.. Ann Arbor, Michigan © -Mfisaya, Ymmmmnfn 1&67

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67—16,349 YAMAMOTO, Masaya, 1929- IMAGE-MAKERS OF JAPAN; A CASE STUDY IN THE IMPACT OF THE AMERICAN PROTESTANT FOREIGN MISSIONARY MOVEMENT, 1859 - 1905. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc.. Ann Arbor, Michigan © -Mfisaya, Ymmmmnfn 1&67 All Rights Reserved IMAGE-MAKERS OF JAPAN: A CASE STUDY IN THE IMPACT OF THE AMERICAN PROTESTANT FOREIGN MISSIONARY MOVEMENT, 1859 - 1905 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masaya Yamamoto, Bungakushi (B.A.), M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by Adviser Department of History FOREWORD We present here a study of the image of Japan in the United States created by the American Protestant foreign missionary movement up to the close of the Russo- Japanese War in 1905. Aside from diplomatic and economic relations, the American Republic's main contact with the Mikado's Empire in the nineteenth century was through the missionary movement. Since this developed on a person-to- person basis, it covered a much wider range than did any other relationships. The Christian missionary enterprise in Japan was, and still is, dominated by American churches. Almost all Christian denominations in the United States have carried on evangelistic work in Nippon. Representatives of all Christian bodies operating in the Empire periodically wrote to their home boards, and their letters and reports were printed in their respective journals. These communications created a definite image of Japan in the minds of church members in the United States. -

Abstract Son Ngoc Thanh, the United States, and The

ABSTRACT SON NGOC THANH, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF CAMBODIA Matthew Jagel, PhD Department of History Northern Illinois University, 2015 Kenton Clymer, Director The Khmer Rouge period of Cambodia’s history is one of the most scrutinized in studies of modern Southeast Asia. What has yet to be examined in sufficient detail is the period leading up to Democratic Kampuchea and the key players of that era, aside from Cambodia’s King (later Prince) Norodom Sihanouk. The story of Son Ngoc Thanh, one of Cambodia’s modern heroes, has yet to be told in detail, and will be a goal of this project. This is not a traditional biography, but instead a study of how Cambodian nationalism grew during the twilight of French colonialism and faced new geopolitical challenges during the Cold War. Throughout Son Ngoc Thanh is the centerpiece. Following a brief stint as Prime Minister under the Japanese, Son Ngoc Thanh’s influence pushed Sihanouk toward a hard-line stance with respect to independence from France, resulting in a free Cambodia by 1953. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Thanh and his group the Khmer Serei (Free Cambodia) exacerbated tensions between Cambodia and its Thai and South Vietnamese neighbors as he attempted to overthrow the Sihanouk government. Thanh also had connections to both American Special Forces and the CIA in South Vietnam. He was involved with the coup to unseat Sihanouk in 1970, and returned to the new Khmer Republic government later that year, only to be pushed out by 1972. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DEKALB, ILLINOIS MAY 2015 SON NGOC THANH, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF CAMBODIA BY MATTHEW JAGEL ©2015 Matthew Jagel A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctoral Director: Kenton Clymer ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. -

Redalyc.Japan in the Works of Pierre Loti and Wenceslau De Moraes

Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies ISSN: 0874-8438 [email protected] Universidade Nova de Lisboa Portugal Vital, Natália Japan in the works of Pierre Loti and Wenceslau de Moraes Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies, núm. 9, december, 2004, pp. 43-73 Universidade Nova de Lisboa Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36100903 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BPJS, 2004,Japan 9, in 43-73 the Works of Pierre Loti and Wenceslau de Moraes 43 JAPAN IN THE WORKS OF PIERRE LOTI AND WENCESLAU DE MORAES Natália Vital 1. Japan: place of passage or chosen homeland (biobibliographical elements) Pierre Loti, whose real name was Julien Viaud, born in 1850 in Roche- fort-sur-Mer, and Wenceslau de Moraes, born in Lisbon in 1854, were two aficionados of exoticism and two authors whose works are so intimately intertwined with their respective lives that it is almost impossible to separate fiction from autobiography. The French writer, a navy officer, embodied, both in his eyes as well as in the eyes of his readers, the ideal of an adventurer who travelled the world (Tahiti, Senegal, Turkey, Britain, Japan, Morocco, the Basque Country, India, Egypt) without ever settling in any single place. His most well known works are exotic novels in which the author/narrator/protagonist, Loti, is an improved version of Julien Viaud, who experiences numerous amorous adventures, all of which are doomed to fail on account of the ever present idea of an inevitable departure. -

1939 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 779 the PRESIDING OFFICER

1939 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 779 The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without objection, the nom Seventy-fifth Congress, to fill the vacancy caused thereon by inations of postmasters are confirmed en bloc. the expiration of the term of Han. Fred H. Brown, formerly That concludes the calendar. a Senator from the State of New Hampshire. RECESS The message also announced that the Vice President Mr. BARKLEY. As in legislative session, I move that the had appointed Mr. BARKLEY and Mr. GIBSON members of the Senate take a recess until 12 o'clock noon tomorrow. joint select committee on the part of the Senate, as pro The motion was agreed to; and <at 5 o'clock and 35 min vided for in the act of February 16, 1889, as amended by the utes p, m.) the Senate took a recess until tomorrow, Thurs act of March 2, 1895, entitled "An act to authorize and pro day, January 26, 1939, at 12 o'clock meridian. vide for the disposition of useless papers in the Executive departments," for the disposition of executive papers in the following departments and agencies: NOMINATIONS 1. Department of Commerce. Executive nominations received by the Senate January 25 2. Department of Labor. <legislative day of January 17), 1939 3. Department of the Navy. UNITED STATES HOUSING AUTHORITY 4. Post Office Department. Jacob Crane, of Illinois, as Assistant Administrator and 5. Farm Credit Administration. Director of Project Planning of the United States Housing 6. Federal Trade Commission. Authority. 7. Works Progress Administration. UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE EXTENSION OF REMARKS Gaston Louis Porterie, of Louisiana, to be United States Mr. -

SCENARIOS SINGAPORE (12/1941 to 3/1942) United States Sets-Up First

PEARL HARBOR (12/1941) the Japanese player loses two or more “Elite Pilots” chits to anti-aircraft rolls, any Japanese win is downgraded to a draw result. The Japanese player loses if he sinks 3 or fewer battleships, or if he only sinks 4 battleships but loses two or more “Elite Pilots” chits to anti-aircraft rolls. If, however, the Japanese player destroys the port, any Japanese loss is upgraded to a draw result. The status of any sunken battleship (i.e., This solitaire scenario only occurs during whether it is salvageable or not) has no the Japanese “Air Movement Step” of the bearing on the victory conditions. “Naval and Air Phase”. SCENARIOS SINGAPORE (12/1941 to 3/1942) United States sets-up first. These scenarios allow players to conduct individual battles or operations of the Pacific Hex E 2501 (Pearl Harbor): Theater instead of the entire campaign from 1937-1945. Each scenario is primarily focused 1 x 1-4/1 fighter-bomber on a specific aspect of combat (air, land and 1 x 1-5 bomber sea), and entails various complexities, as well 1 x 1-12 bomber as varying playing times (the first scenario is 1 x 0(1)-4-46 destroyer (depleted) [IN PORT] the shortest.) These scenarios and rules will 1 x 0(1)-6-47 destroyer (depleted) [IN PORT] 1 x 0(1)-3-45 destroyer [IN PORT] be intuitive to experienced players. 1 x 0(1)-3-45 destroyer (depleted) [IN PORT] 1 x 0(1)-3-45 destroyer (depleted) [AT SEA] Some scenarios incorporate optional rules, 1 x 0(1)-3-40 destroyer (depleted) [IN PORT] such as “Elite Pilots” and “Naval Mines”, and 1 x 1-10-42 light cruiser [IN PORT] This two-player scenario starts during the are recommended, but not mandatory.