FOOTBALL AS a FACTOR (AND a REFLECTION) of INTERNATIONAL POLITICS Pascal Boniface 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interstate Peacekeeping: Causal Mechanisms and Empirical Effects

INTERSTATE PEACEKEEPING: CAUSAL MECHANISMS AND EMPIRICAL EFFECTS Virginia Page Fortna* Department of Political Science & Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies Columbia University permanent address 420 W. 118th Street New York NY 10027 w. 212 854-0021 h. 212 662-5395 f. 212 864-1686 AY 2004-2005 address Hoover Institution Stanford University Stanford CA 94305 w. 650 723-0746 c. 503 548-7429 f. 650 723-1687 email: [email protected] Version: September 14, 2004 * The author owes debts of gratitude to more people than can be listed here for help and feedback with the project of which this paper is a part. She thanks in particular, Nisha Fazal, Hein Goemans, Lise Howard, Bob Jervis, Bob Keohane, Lisa Martin, Jack Snyder, Alan Stam, Barb Walter, and Suzanne Werner. This research was made possible by grants from the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. INTERSTATE PEACEKEEPING: CAUSAL MECHANISMS AND EMPIRICAL EFFECTS ABSTRACT Peacekeeping is perhaps the international community’s most important tool for maintaining peace in the aftermath of war. Its practice has evolved significantly in the past ten or fifteen years as it has been used increasingly in civil wars. However, traditional peacekeeping between states is not well understood. Its operation is under-theorized and its effects under-tested. This article explores the causal mechanisms through which peacekeepers keep peace, and examines its empirical effects after interstate wars. To take the endogeneity of peacekeeping into account, it also examines where peacekeepers tend to be deployed. -

Messi, Ronaldo, and the Politics of Celebrity Elections

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Research Online Messi, Ronaldo, and the politics of celebrity elections: voting for the best soccer player in the world LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/101875/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Anderson, Christopher J., Arrondel, Luc, Blais, André, Daoust, Jean François, Laslier, Jean François and Van Der Straeten, Karine (2019) Messi, Ronaldo, and the politics of celebrity elections: voting for the best soccer player in the world. Perspectives on Politics. ISSN 1537-5927 https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719002391 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ Messi, Ronaldo, and the Politics of Celebrity Elections: Voting For the Best Soccer Player in the World Christopher J. Anderson London School of Economics and Political Science Luc Arrondel Paris School of Economics André Blais University of Montréal Jean-François Daoust McGill University Jean-François Laslier Paris School of Economics Karine Van der Straeten Toulouse School of Economics Abstract It is widely assumed that celebrities are imbued with political capital and the power to move opinion. To understand the sources of that capital in the specific domain of sports celebrity, we investigate the popularity of global soccer superstars. -

The Economy of Greece and the FIFA Ranking of Its National Football Team

Athens Journal of Sports - Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021 – Pages 161-172 The Economy of Greece and the FIFA Ranking of its National Football Team By Gregory T. Papanikos* The purpose of this study is to compare the performance of the Greek economy with the FIFA ranking of the Greek National Football Team in order to find out whether there exists some sort of statistical association. The period under consideration starts with the establishment of the European and Monetary Union in 1992 and ends with the current year of 2021. In 1992, FIFA started to rank national football teams which restricts the extent of time to be used in this study. The descriptive evidence presented in this paper shows that there exists strong positive association between the level of real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Greece and the ranking of its national football team. Keywords: FIFA, Greece, Football, GDP, European Union, National Teams. Introduction Most Greeks would agree that 2004 was a year to be remembered by Greece’s current and future generations. It was an exceptional year. The Greek economy was booming, and benefited from its full membership in the Eurozone; a process which started much earlier in 1992 and was completed by the adoption of the Euro in 2002. In the beginning of the year of 2004, the city of Athens, as well as other Greek cities, were preparing to welcome the youth of the world to celebrate, once again, the modern Olympic Games in its birthplace. Athens in the beginning of 2004 had a brand-new airport, a brand-new ring road, a brand-new metro system and many other smaller and bigger infrastructures which were built either because they were required by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), or by Greece’s own initiative. -

Revue Internationale De La Croix-Rouge Et Bulletin Des Societes De La Croix-Rouge

REVUE INTERNATIONALE DE LA CROIX-ROUGE ET BULLETIN DES SOCIETES DE LA CROIX-ROUGE SUPPLEMENT First Year, I948 GENEVE 1948 SUPPLEMENT VOL. I REVUE INTERNATIONALE DE LA CROIX-ROUGE ET BULLETIN DES SOCIETES DE LA CROIX-ROUGE SUPPLEMENT March,1948 NO·3 CONTENTS Page Mission of the International Committee in Palestine . .. 42 Mission of the International Committee to the United States and to Canada . 43 The Far Eastern Conflict (Part I) 45 Published by Comite international de la Croix-Rouge, Geueve Editor: Louis Demolis MISSION OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE IN PALESTINE In pursuance of a request made by the Government of the mandatory Power in Palestine, the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva, who had previously been authorized to visit the camps of persons detained in consequence of recent events, have despatched a special mission to Palestine. This . mission has been instructed to study, in co-operation with all parties, the problems arising from the humanitarian work which appears to be indispensable in view of the present situation. The Committee's delegates have met on all hands with a most frie~dly reception. During the last few weeks, they have had talks with the Government Authorities and the Arab and Jewish representatives; they have offered to all concerned the customary services of the Committee as a neutral intermediary, having in mind especially the protection and care of wounded, sick and prisoners. During their tour of the country the Committee's delegates visited a large number of hospitals and refugee camps, and collected information on the present needs in hospital staff, doctors and nurses, as well as in ambulances and medical supplies. -

War As a Constitutive Moment

Dodging a Bullet: Democracy’s Gains in Modern War* Paul Starr That war drives state-building is virtually a truism of historical sociology, summed up in the late Charles Tilly’s well-known aphorism that states make war, and war makes states. (Tilly, 1990) But if war and state-building merely reinforce each other, why have liberal democracies flourished and proliferated during the past two centuries when war reached unprecedented dimensions? Why not militaristic autocracies? What role, if any, has war played in the formation and spread of liberal democratic regimes? To raise these questions is not to suggest that war is one of democracy’s primary causes, but rather to ask how democracy and, more particularly, liberal democracy dodged a bullet--a bullet that, according to many ancient and plausible theories, might well been fatal. The belief that democracy is a liability in war has been a staple of political thought, beginning with Thucydides. If liberalism and democracy had been sources of severe military disadvantage during the past two centuries, liberal democratic regimes should have perished in wars as they were conquered and eliminated by other states, or when their own populations rose up to overthrow them in the wake of defeat, or because they were forced to abandon their institutions in order to survive. That this was not their fate suggests a range of possibilities. At a minimum, their institutions have not been a disabling handicap in war, and no consistent relationship may exist between war and democracy. Alternatively, war may have contributed to the spread of democratic regimes if democracy itself or features correlated with democracy have increased the chances of a regime’s survival in war, or if war has promoted changes favorable to democratic institutions. -

Thebestway FIFA 14 | GOOGLE GLASS | PS4 | DEAD MOUSE + MORE

THE LAUNCH ISSUE T.O.W.I.E TO MK ONLY THE BEST WE LET MARK WRIGHT WE TRAVEL TO CHELSEA AND JAMESIII.V. ARGENT MMXIIIAND TALK BUSINESS LOOSE IN MILTON KEYNES WITH REFORMED PLAYBOY CALUM BEST BAG THAT JOB THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO HOT HATCH WALKING AWAY WITH WE GET HOT AND EXCITED THE JOB OFFER OVER THE LATEST HATCHES RELEASED THIS SUMMER LOOKING HOT GET THE STUNNING LOOKS ONE TOO MANY OF CARA DEVEVINGNE DO YOU KNOW WHEN IN FIVE SIMPLE STEPS ENOUGH IS ENOUGH? THEBESTway FIFA 14 | GOOGLE GLASS | PS4 | DEAD MOUSE + MORE CONTENTS DOING IT THE WRIGHT WAY - THE TRENDLIFE LAUNCH PARTY The Only Way To launch TrendLife Magazine saw Essex boys Mark Wright and James ‘Arg’ Argent join us at Wonderworld in Milton Keynes alongside others including Corrie’s Michelle Keegen. Take a butchers at page 59 me old china. 14 MAIN FEATURES CALUM BEST ON CALUM BEST We sit down with Calum Best at 7 - 9 Chelsea’s Broadway House to discuss his new look on life, business and of course, the ladies. 12 MUST HAVES FOR SUMMER Get your credit card at the ready as 12 we give you ‘His and Hers’ essentials for this summer. You can thank us later. NEVER MIND THE SMALLCOCK Ladies, you have all been there and if 18 you have not, you will. What do you do when you are confronted with the ultimate let down? Fight or flight? #TRENDLIFEAWARDS REGISTER TODAY FOR THE EVENT OF 2013 WHATS NEW FIFA 14 PREVIEW | 35 No official release date. -

Nielsen Sports Women’S Football 2019 with Supporting Social Media Insights from Introduction

NIELSEN SPORTS WOMEN’S FOOTBALL 2019 WITH SUPPORTING SOCIAL MEDIA INSIGHTS FROM INTRODUCTION By almost any measure, the 2019 FIFA Women’s World Cup is poised to be the biggest yet. France will host the eighth edition of the tournament across nine cities – Lyon, Grenoble, Le Havre, Montpellier, Nice, Paris, Reims, Rennes and Valenciennes. With prime-time coverage expected across Europe, viewership is set to be up on the last tournament. At the same time, genuine commercial momentum is building with FIFA partners and team sponsors, notably Adidas and Nike, launching the most ambitious activation programmes yet seen for a women’s football event. Women’s club football is also growing around the world, an important development which looks set to ensure there is less of a spike in interest in women’s football around major international events like the World Cup as the club game sustains interest in the periods between them. There have been record attendances over the last year in Mexico, Spain, Italy and England, with rising interest levels and unprecedented investment from sponsors, while at a regional level, in Europe, UEFA is this season hosting the Women’s Champions League final in a different city from the men’s event for the first time. This report, put together by Nielsen Sports and Leaders, offers a snapshot of the health of women’s football as the World Cup gets underway, examining current interest levels, the makeup of fans and what the future may bring as it increasingly professionalises. On the eve of the FIFA Women’s World Cup, we have also worked with Facebook to look at interest in the women’s game across its platforms. -

What Is Wrong with Playing High? Cesar R

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The College at Brockport, State University of New York: Digital Commons @Brockport The College at Brockport: State University of New York Digital Commons @Brockport Kinesiology, Sport Studies and Physical Education Kinesiology, Sport Studies and Physical Education Faculty Publications 2009 What is Wrong with Playing High? Cesar R. Torres The College at Brockport, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/pes_facpub Part of the Kinesiology Commons Repository Citation Torres, Cesar R., "What is Wrong with Playing High?" (2009). Kinesiology, Sport Studies and Physical Education Faculty Publications. 14. https://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/pes_facpub/14 Citation/Publisher Attribution: Torres, C.R. (2009). What is Wrong with Playing High? Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 36(1), 1-21. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Kinesiology, Sport Studies and Physical Education at Digital Commons @Brockport. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kinesiology, Sport Studies and Physical Education Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @Brockport. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 2009, 36, 1-21 © 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc. What Is Wrong With Playing High? Cesar R. Torres The debate over playing football, or “soccer” as the game is known to North Americans, at high altitudes reached new heights in 2007 and 2008. Late in May 2007, concerned about mounting criticism, the Fédération Internationale de Foot- ball Association (FIFA) decided to ban games under its jurisdiction at altitudes above 2,500 meters. -

Wars Since 1945: an Introduction

Wars since 1945: An Introduction Beatrice Heuser1 While most Europeans lived through an exceptionally peaceful period of histo- ry, termed ‘The Long Peace’ by John Lewis Gaddis,2 the populations of other continents were decidedly less fortunate. What was a ‘Cold War’ for the Euro- peans was anything but ‘cold’ for the Koreans, Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians, for most Arab peoples, the Afghans, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, and Indians, the populations of the Congo, Kenya, Nigeria, Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Ethiopia, Somalia and Eritrea, and of most of Latin America. How, then, can one be so sanguine as to characterise this period as that of a ‘Cold War’ or a ‘long peace’? The reason is that the long-expected Third World War has not (yet?) taken place. It was the prospect of such a Third World War, a ‘total’ and in all probability nuclear war, that attracted the attention of con- cerned minds in Europe and North America, the cultures that over centuries produced most publications on the subjects of war, strategy, military affairs and international relations. 1. An overview Admittedly, Americans, Britons, Frenchmen, Belgians, Portuguese and the Dutch were soon reminded of the existence of a world outside the Europe- centric East-West conflict. Almost immediately after the end of the Second World War, Britain and France became involved in decolonisation wars in Asia and Africa, and America woke up to the enduring reality of lesser wars with Korea. American strategists like Robert Osgood turned to Clausewitzian con- cepts to define these: they called them ‘limited wars’, since no nuclear weapons were used, and because they did not escalate to global war.3 While many of them recognised the continuing occurrence of such non-nuclear, non-global wars, Americans (and indeed Britons and Frenchmen) tended to see them as part of the larger framework of the Cold War. -

Julien's Auctions Presents Property from the Estate

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ALFREDO DI STÉFANO PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS PRESENTS PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ALFREDO DI STÉFANO REAL MADRID’S LEGENDARY “PLAYER OF THE CENTURY” FOOTBALLER’S FIVE CONSECUTIVE UEFA EUROPEAN CHAMPIONS CUP WINNERS MEDALS FROM 1956-1960 TO STAND ATOP THE AUCTION PODIUM Di Stéfano’s Ballon d’Or Awards Including his 1989 Super Ballon d’Or, Iconic 1950s Real Madrid White Number 9 Jersey, Spanish National Team Red and Blue 1960s Number 9 Jerseys, Spanish League (La Liga) Champions Trophies, Plaques, Coins, Personal Items and More to Dazzle the Two-Day Auction Event in London THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 23RD AND FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 24TH, 2021 Los Angeles, California – (July 28th, 2021) – Julien’s Auctions announced today PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ALFREDO DI STÉFANO, the world record-breaking auction house to the stars’ tribute to the legendary Real Madrid football champion, taking place Thursday, September 23rd and Friday, September 24th, 2021, live at Mall Galleries in London and online at www.juliensauctions.com. PAGE 1 Julien’s Auctions | 8630 Hayden Place, Culver City, California 90232 | Phone: 310-836-1818 | Fax: 310-836-1818 © 2003-2021 Julien’s Auctions JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ALFREDO DI STÉFANO PRESS RELEASE There are 796 historic sports artifacts from the life and career of Alfredo Di Stéfano, one of the greatest footballers of all time and the number four ranking “Player of the Century” on France Football’s storied list that includes immortals of the game, Pelé and Diego Maradona, will be presented in the two-day auction event. -

Women's Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011

Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 A Project Funded by the UEFA Research Grant Programme Jean Williams Senior Research Fellow International Centre for Sports History and Culture De Montfort University Contents: Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971- 2011 Contents Page i Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Introduction: Women’s Football and Europe 1 1.1 Post-war Europes 1 1.2 UEFA & European competitions 11 1.3 Conclusion 25 References 27 Chapter Two: Sources and Methods 36 2.1 Perceptions of a Global Game 36 2.2 Methods and Sources 43 References 47 Chapter Three: Micro, Meso, Macro Professionalism 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Micro Professionalism: Pioneering individuals 53 3.3 Meso Professionalism: Growing Internationalism 64 3.4 Macro Professionalism: Women's Champions League 70 3.5 Conclusion: From Germany 2011 to Canada 2015 81 References 86 i Conclusion 90 4.1 Conclusion 90 References 105 Recommendations 109 Appendix 1 Key Dates of European Union 112 Appendix 2 Key Dates for European football 116 Appendix 3 Summary A-Y by national association 122 Bibliography 158 ii Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 Abbreviations and Acronyms AFC Asian Football Confederation AIAW Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women ALFA Asian Ladies Football Association CAF Confédération Africaine de Football CFA People’s Republic of China Football Association China ’91 FIFA Women’s World Championship 1991 CONCACAF Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football CONMEBOL -

CPY Document Title

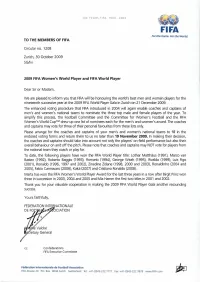

100 YEARS FIFA 1904 2004 For the Game. For the WorLd. TO THE MEMBERS OF FIFA Circular no. 1208 Zurich, 30 October 2009 SG/lvi 2009 FIFA Women's World Player and FIFA World Player Dear Sir or Madam, We are pleased to inform you that FIFA will be honouring the world's best men and women players for the nineteenth successive year at the 2009 FIFA World Player Gala in Zurich on 21 December 2009. The enhanced voting procedure that FIFA introduced in 2004 will again enable coaches and captains of men's and women's national teams to nominate the three top male and female players of the year. To simplify this process, the Football Committee and the Committee for Women's Football and the FIFA Women's World CUpTM drew up one list of nominees each for the men's and women's award. The coaches and captains may vote for th ree of their personal favourites from these lists only. Please arrange for the coaches and captains of your men's and women's national teams to fill in the enclosed voting forms and return them to us no later than 19 November 2009. In making their decision, the coaches and captains should take into account not only the players' on-field performance but also the ir overall behaviour on and off the pitch. Please note that coaches and captains may NOT vote for players from the national team they coach or play for. To date, the following players have won the FIFA World Player title: Lothar Matthsus (1991), Marco van Basten (1992), Roberto Baggio (1993), Romario (1994), George Weah (1995), Rivaldo (1999), Luis Figo (2001), Ronaldo (1996, 1997 and 2002), Zinedine Zidane (1998, 2000 and 2003), Ronaldinho (2004 and 2005), Fabio Cannavaro (2006), Kaka (2007) and Cristiano Ronaldo (2008).