Farewell to Descartes 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Existentialism of Martin Buber and Implications for Education

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 69-4919 KINER, Edward David, 1939- THE EXISTENTIALISM OF MARTIN BUBER AND IMPLICATIONS FOR EDUCATION. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1968 Education, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE EXISTENTIALISM OF MARTIN BUBER AND IMPLICATIONS FOR EDUCATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Edward David Kiner, B.A., M.A. ####*### The Ohio State University 1968 Approved by Adviser College of Education This thesis is dedicated to significant others, to warm, vital, concerned people Who have meant much to me and have helped me achieve my self, To people whose lives and beings have manifested "glimpses" of the Eternal Thou, To my wife, Sharyn, and my children, Seth and Debra. VITA February 14* 1939 Born - Cleveland, Ohio 1961......... B.A. Western Reserve University April, 1965..... M.A. Hebrew Union College Jewish Institute of Religion June, 1965...... Ordained a Rabbi 1965-1968........ Assistant Rabbi, Temple Israel, Columbus, Ohio 1967-1968...... Director of Religious Education, Columbus, Ohio FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: Philosophy of Education Studies in Philosophy of Education, Dr. Everett J. Kircher Studies in Curriculum, Dr. Alexander Frazier Studies in Philosophy, Dr. Marvin Fox ill TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION............................................. ii VITA ................................................... iii INTRODUCTION............................ 1 Chapter I. AN INTRODUCTION TO MARTIN BUBER'S THOUGHT....... 6 Philosophical Anthropology I And Thou Martin Buber and Hasidism Buber and Existentialism Conclusion II. EPISTEMOLOGY . 30 Truth Past and Present I-It Knowledge Thinking Philosophy I-Thou Knowledge Complemented by I-It Living Truth Buber as an Ebdstentialist-Intuitionist Implications for Education A Major Problem Education, Inclusion, and the Problem of Criterion Conclusion III. -

Karl Polanyi. Life and Works of an Epochal Thinker. (Ebook / PDF)

BRIGITTE AULENBACHER, MARKUS MARTERBAUER, ANDREAS NOVY, KARI POLANYI LEVITT, ARMIN THURNHER (EDS.) KARL POLANYI The Life and Works of an Epochal Thinker Karl Polanyi BRIGITTE AULENBACHER, MARKUS MARTERBAUER, ANDREAS NOVY, KARI POLANYI LEVITT, ARMIN THURNHER (EDS.) KARL POLANYI The Life and Works of an Epochal Thinker Translated by Jan-Peter Herrmann and Carla Welch FALTERVERLAG The translation has been funded by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. ISBN 978-3-85439-689-5 © 2020 Falter Verlagsgesellschaft m.b.H. 1011 Wien, Marc-Aurel-Straße 9 T: +43/1/536 60-0, F: +43/1/536 60-935 E: [email protected], [email protected] W: faltershop.at All rights reserved. Editors: Brigitte Aulenbacher, Markus Marterbauer, Andreas Novy, Kari Polanyi Levitt, Armin Thurnher Translator: Jan-Peter Herrmann, Carla Welch Illustrations: P.M. Hoffmann Layout: Marion Großschädl Production: Susanne Schwameis Printed by myMorawa With this book, we care about the packaging dispensed with plastic wrap. Table of ConTenT Brigitte Aulenbacher, Andreas Novy: Acknowledgements 7 Marguerite Mendell: Foreword 9 Armin Thurnher: Foreword of the German edition 12 I. The Renaissance Brigitte Aulenbacher, Veronika Heimerl, Andreas Novy: The Limits of a Market Society 17 Armin Thurnher: ‘Many graze on Polanyi’s pasture’ 24 Michael Burawoy: Fictitious Commodities and the Three Waves of Marketization 33 II. The Personal and the Historical Michael Burawoy: ‘Wherever my father lived he was engaged in whatever was going on’. Shaping The Great Transformation: a conversation with Kari Polanyi Levitt 41 Michael Brie, Claus Thomasberger: Freedom in a Threatened Society 53 Veronika Helfert: Born a Rebel, Always a Rebel 61 Andreas Novy: From Development Economist to Trailblazer of the Polanyi Renaissance 66 Franz Tödtling: From Physical Chemistry to the Philosophy of Knowledge 74 Michael Mesch: Milieus in Karl Polanyi’s Life 82 Gareth Dale: Karl Polanyi in Budapest 94 Robert Kuttner: Karl Polanyi and the Legacy of Red Vienna 98 Sabine Lichtenberger: ‘The Earliest Beginnings of His Later Teaching Life’ 101 III. -

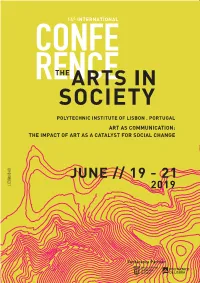

Art As Communication: Y the Impact of Art As a Catalyst for Social Change Cm

capa e contra capa.pdf 1 03/06/2019 10:57:34 POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE OF LISBON . PORTUGAL C M ART AS COMMUNICATION: Y THE IMPACT OF ART AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CM MY CY CMY K Fifteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society Against the Grain: Arts and the Crisis of Democracy NUI Galway Galway, Ireland 24–26 June 2020 Call for Papers We invite proposals for paper presentations, workshops/interactive sessions, posters/exhibits, colloquia, creative practice showcases, virtual posters, or virtual lightning talks. Returning Member Registration We are pleased to oer a Returning Member Registration Discount to delegates who have attended The Arts in Society Conference in the past. Returning research network members receive a discount o the full conference registration rate. ArtsInSociety.com/2020-Conference Conference Partner Fourteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society “Art as Communication: The Impact of Art as a Catalyst for Social Change” 19–21 June 2019 | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal www.artsinsociety.com www.facebook.com/ArtsInSociety @artsinsociety | #ICAIS19 Fourteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society www.artsinsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). -

Master Plan BICYCLE-PEDESTRIAN FACILITIES and the GREEN LOOP

Cultural District Historic Turf Area at PSU Children’s Foundation Planting Deciduous Trees and Canopy Native Plants at Farewell Turf Areas and Trees Along 1 3 5 7 9 11 Rose Beds 13 Planting Character- Playground at Shattuck Hall in Brick Tree Wells to Orpheus Fountain North-South Walkways Shemanski Fountain (c.1929) 2 University District Historic University District Historic Cultural District Historic Turf Area and Young Tree Planted Cultural District Deciduous Trees Planting Character- Shattuck Hall 4 6 Planting Character- 8 10 12 14 Planting Character- Deciduous Tree Canopy In Shade of Mature Elms Planting Character and Canopy Foundation Planting (1914) Farewell to Orpheus Fountain (1990) Lincoln Statue (1975) 2 1 12 7 10 13 5 8 9 11 4 14 6 3 Tree Assessment ° 0 50 100 200 FEET TREE ASSESSMENT AND LANDSCAPE CHARACTER SOUTH PARK BLOCKS // master plan Green Metal Fence at Bronze Clock on Concrete Theodore Roosevelt, Joseph Shemanski 1 3 Holon and Plaque 5 7 Junior League of Portland Plaque 9 11 Abraham Lincoln Statue 13 PSU Children’s Playground Pedestal at Mill Street Rough Rider Fountain (c.1929) Farewell to Vanport College Plaque Utility Box and South Park Block 2 Pole on Concrete Pedestal 4 6 8 Peace Chant 10 Great Plank Road Plaque 12 14 Benson Bubblers at Salmon Orpheus Fountain at Lincoln Hall Light Poles and Luminaires 10TH 10TH AVE Montgomery HALL Residence Hall Millar Library HARRISON Peter W Stott Center Temple Temple Temple Masonic & Viking Pavilion Masonic Masonic Portland PortlandPortland Art Museum ArtArt Museum Museum Park Plaza Apartments MONTGOMERY Vue Apartments MILL MARKET Manor Manor Manor Jeanne Jeanne Jeanne Building Building Building Hotel Hotel ChurchChurch Hotel Church Christ, Scientist Christ, Scientist Christ, Scientist Sixth Church of Sixth Church of Sixth Church of LutheranLutheran Lutheran Apartment Apartment Apartment Apartments COLLEGE Apartments Apartments St. -

Pattern and Process Second Edition Monica G. Turner Robert H. Gardner

Monica G. Turner Robert H. Gardner Landscape Ecology in Theory and Practice Pattern and Process Second Edition L ANDSCAPE E COLOGY IN T HEORY AND P RACTICE M ONICA G . T URNER R OBERT H . G ARDNER LANDSCAPE ECOLOGY IN THEORY AND PRACTICE Pattern and Process Second Edition Monica G. Turner University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Zoology Madison , WI , USA Robert H. Gardner University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Frostburg, MD , USA ISBN 978-1-4939-2793-7 ISBN 978-1-4939-2794-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4939-2794-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015945952 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London © Springer-Verlag New York 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

The Balance of Personality

The Balance of Personality The Balance of Personality CHRIS ALLEN PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY The Balance of Personality by Chris Allen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. The Balance of Personality Copyright © by Chris Allen is licensed under an Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, except where otherwise noted. Contents Preface ix Acknowledgements x Front Cover Photo: x Special Thanks to: x Open Educational Resources xi Introduction 1 1. Personality Traits 3 Introduction 3 Facets of Traits (Subtraits) 7 Other Traits Beyond the Five-Factor Model 8 The Person-Situation Debate and Alternatives to the Trait Perspective 10 2. Personality Stability 17 Introduction 18 Defining Different Kinds of Personality Stability 19 The How and Why of Personality Stability and Change: Different Kinds of Interplay Between Individuals 22 and Their Environments Conclusion 25 3. Personality Assessment 30 Introduction 30 Objective Tests 31 Basic Types of Objective Tests 32 Other Ways of Classifying Objective Tests 35 Projective and Implicit Tests 36 Behavioral and Performance Measures 38 Conclusion 39 Vocabulary 39 4. Sigmund Freud, Karen Horney, Nancy Chodorow: Viewpoints on Psychodynamic Theory 43 Introduction 43 Core Assumptions of the Psychodynamic Perspective 45 The Evolution of Psychodynamic Theory 46 Nancy Chodorow’s Psychoanalytic Feminism and the Role of Mothering 55 Quiz 60 5. Carl Jung 63 Carl Jung: Analytic Psychology 63 6. Humanistic and Existential Theory: Frankl, Rogers, and Maslow 78 HUMANISTIC AND EXISTENTIAL THEORY: VIKTOR FRANKL, CARL ROGERS, AND ABRAHAM 78 MASLOW Carl Rogers, Humanistic Psychotherapy 85 Vocabulary and Concepts 94 7. -

Growing Semi-Living Art

Growing Semi-Living Art Ionat Zurr Bachelor of Arts (Hi Honours) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts 2008 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 4 Abstract 5-6 Introduction 7-30 Chapter 1 31-49 The Extended Body Chapter 2 50-93 The Ecology of Parts: The History of Partial Life Chapter 3 94-129 The Ethics of the Semi-Livings* Chapter 4 130-154 The Ethics and Politics of Experiential Engagement with the Manipulation of Life* Chapter 5 155-176 Big Pigs, Small Wings: on Genohype and Artistic Autonomy* Chapter 6 177-224 Tissue Art – A Taxonomical Crisis: A survey of artists working with tissue Chapter 7 225-239 Towards a New Class of Being – The Extended Body* Conclusion 240-262 The Ecology of Parts 2 Appendix 1 A partial list of articles written and/or citing about the Tissue Culture & Art Project 263 - 267 Appendix 2 A chronological listing and a short description of the TC&A Projects 268-282 Appendix 3 List of TC&A Project Installations and Exhibitions 283-286 List of Figures 287-289 Bibliography 290-299 Endnotes & Refrences 300-333 * An earlier version of chapter three has been published as Ionat Zurr and Oron Catts, The Ethical Claims of Bioart: Killing the Other or Self Cannibalism, AAANZ Journal of Art: Art and Ethics, 4:2 (2003) and 5:1 (2004) 167–188. It won the 2003 Power Institute/AAANZ Prize for Best Journal Article. * An earlier version of chapter four is due to be published as Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr The Ethics and Politics of Experiential Engagement with the Manipulation of Life, in Tactical Biopolitics: Art, Activism, and Technoscience, edited by Beatriz da Costa and Kavita Philip (MIT Press, forthcoming June 2008). -

The JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR #69

1 82658 00098 1 The JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FALL 2016 FALL $10.95 #69 All characters TM & © Simon & Kirby Estates. THE Contents PARTNERS! OPENING SHOT . .2 (watch the company you keep) FOUNDATIONS . .3 (Mr. Scarlet, frankly) ISSUE #69, FALL 2016 C o l l e c t o r START-UPS . .10 (who was Jack’s first partner?) 2016 EISNER AWARDS NOMINEE: BEST COMICS-RELATED PERIODICAL PROSPEAK . .12 (Steve Sherman, Mike Royer, Joe Sinnott, & Lisa Kirby discuss Jack) KIRBY KINETICS . .18 (Kirby + Wood = Evolution) FANSPEAK . .22 (a select group of Kirby fans parse the Marvel settlement) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .29 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) KIRBY OBSCURA . .30 (Kirby sees all!) CLASSICS . .32 (a Timely pair of editors are interviewed) RE-PAIRINGS . .36 (Marvel-ous cover recreations) GALLERY . .39 (some Kirby odd couplings) INPRINT . .49 (packaging Jack) INNERVIEW . .52 (Jack & Roz—partners for life) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .60 (Sandman & Sandy revamped) OPTIKS . .62 (Jack in 3-D Land) SCULPTED . .72 (the Glenn Kolleda incident) JACK F.A.Q.s . .74 (Mark Evanier moderates the 2016 Comic-Con Tribute Panel, with Kevin Eastman, Ray Wyman Jr., Scott Dunbier, and Paul Levine) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .92 (as a former jazz bass player, the editor of this mag was blown away by the Sonny Rollins letter...) PARTING SHOT . .94 (never trust a dwarf with a cannon) Cover inks: JOE SINNOTT from Kirby Unleashed Cover color: TOM ZIUKO If you’re viewing a Digital Edition of this publication, PLEASE READ THIS: This is copyrighted material, NOT intended Direct from Roz Kirby’s sketchbook, here’s a team of partners that holds a for downloading anywhere except our website or Apps. -

Past Tense, 2011

Portland State University PDXScholar Remembering Portland State: Historical Past Tense columns of the RAPS Sheet Reflections and ersonalP Perspectives on Our University 2011 Past Tense, 2011 Retired Association of Portland State Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/rememberpsu_past Part of the Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Retired Association of Portland State, "Past Tense, 2011" (2011). Past Tense columns of the RAPS Sheet. 3. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/rememberpsu_past/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Past Tense columns of the RAPS Sheet by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. RAPS club reports Book Club: ‘Let the Great World Spin’ PAST TENSE The RAPS Book Club meets Tuesday, Jan. 18, at 2:00 pm at the home of Betsey Brown at Holiday Park Plaza, 1300 Pres. Ramaley champions redesign of seal NE 16 th Avenue in Portland. Contact her at 503-280-2334 or [email protected] to RSVP and for directions. NOTE THE TIME CHANGE. We will discuss Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann. The book is described as follows on the inside cover: In the dawning light of a late-summer morning, the people of lower Manhattan stand hushed, staring up in disbelief at the Twin Towers. It is 1969-1990 1991-present August 1974, and a mysterious tightrope walker udith Ramaley was hired in 1990 to be the seventh is running, dancing, leaping between the towers, President of Portland State University – and the first suspended a quarter mile above the ground. -

10Th ANNIVERSARY (DC) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

10th ANNIVERSARY (DC) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Batgirl, 9 Superman™, 24 Batman™, 4 Superman™ Batman™ (Black Lantern), 26 (Black Lantern), 27 Blue Beetle (Jaime Reyes), 12 Wonder Woman, 5 Blue Beetle (Ted Kord), 19 Wonder Woman (Black Lantern), 25 Brainiac (Milton Fine), 8 Brainiac (“True” Brainiac), 15 Catwoman (80s), 11 Catwoman (90s), 18 The Flash (Wally West), 13 The Flash (Jay Garrick), 21 Green Lantern (Hal Jordan), 7 Green Lantern (Alan Scott), 14 John Jones, 6 Lex Luthor (Classic), 16 Lex Luthor (Armor), 23 Martian Manhunter, 22 Nightwing, 10 Oracle, 20 Robin, 17 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 BATMAN™ Batman Family, Detective, Gotham City, Justice League GOOD SOLDIER (Leadership) Battlefield Promotion:Rise When Batman hits one or more opposing characters, after actions resolve, place a Promotion Token on his character card. -

Heroclix Campaign

HeroClix Campaign DC Teams and Members Core Members Unlock Level A Unlock Level B Unlock Level C Unless otherwise noted, team abilities are be purchased according to the Core Rules. For unlock levels listing a Team Build (TB) requisite, this can be new members or figure upgrades. VPS points are not used for team unlocks, only TB points. Arkham Inmates Villain TA Batman Enemy Team Ability (from the PAC). SR Criminals are Mooks. A 450 TB points of Arkham Inmates on the team. B 600 TB points of Arkham Inmates on the team. Anarky, Bane, Black Mask, Blockbuster, Clayface, Clayface III, Deadshot, Dr Destiny, Firefly, Cheetah, Criminals, Ambush Bug. Jean Floronic Man, Harlequin, Hush, Joker, Killer Croc, Mad Hatter, Mr Freeze, Penguin, Poison Ivy, Dr Arkham, The Key, Loring, Kobra, Professor Ivo, Ra’s Al Ghul, Riddler, Scarecrow, Solomon Grundy, Two‐Face, Ventriloquist. Man‐Bat. Psycho‐Pirate. Batman Enemy See Arkham Inmates, Gotham Underground Villain Batman Family Hero TA The Batman Ally Team Ability (from the PAC). SR Bat Sentry may purchased in Multiples, but it is not a Mook. SR For Batgirl to upgrade to Oracle, she must be KOd by an opposing figure. Environment or pushing do not count. If any version of Joker for KOs Level 1 Batgirl, the player controlling Joker receives 5 extra points. A 500 TB points of Batman members on the team. B 650 TB points of Batman members on the team. Azrael, Batgirl (Gordon), Batgirl (Cain), Batman, Batwoman, Black Catwoman, Commissioner Gordon, Alfred, Anarky, Batman Canary, Catgirl, Green Arrow (Queen), Huntress, Nightwing, Question, Katana, Man‐Bat, Red Hood, Lady Beyond, Lucius Fox, Robin (Tim), Spoiler, Talia. -

Systems Archetypes I

TOOLBO X REPR INTS ERIE S SYSTEMS ARCHETYPES I Diagnosing Systemic Issues and Designing High-Leverage Interventions 2 BY DANIEL H. KIM THE TOOLBOX REPRINT SERIES Systems Archetypes I: Diagnosing Systemic Issues and Designing High-Leverage Interventions Systems Archetypes II: Using Systems Archetypes to Take Effective Action Systems Archetypes III: Understanding Patterns of Behavior and Delay Systems Thinking Tools: A User’s Reference Guide The “Thinking” in Systems Thinking: Seven Essential Skills Systems Archetypes I: Diagnosing Systemic Issues and Designing High-Leverage Interventions by Daniel H. Kim © 1992, 2000 by Pegasus Communications, Inc. First printing August 1992. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Acquiring editor: Kellie Wardman O’Reilly Consulting editor: Ginny Wiley Project editor: Lauren Keller Johnson Production: Nancy Daugherty ISBN 1-883823-00-5 PEGASUS COMMUNICATIONS, INC. One Moody Street Waltham, MA 02453-5339 USA Phone 800-272-0945 / 781-398-9700 Fax 781-894-7175 [email protected] [email protected] www.pegasuscom.com 2008 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 2 A Palette of Systems Thinking Tools 4 Systems Archetypes at a Glance 6 Organizational Addictions: Breaking the Habit 8 Balancing Loops with Delays: Teeter-Tottering on Seesaws 10 “Drifting Goals”: The “Boiled Frog”