Burial Practices in Southern Appalachia. Donna W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

Urban Poverty in Vietnam – a View from Complementary Assessments

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT HUMAN SETTLEMENTS WORKING PAPER SERIES POVERTY REDUCTION IN URBAN AREAS – 40 Urban pov erty in V iet nam – a vi ew from com plementary asses sments by HOANG XUAN THANH, with TRUONG TUAN ANH and DINH THI THU PHUONG OCTOBER 2013 HUMAN SETTLEMENTS GROUP Urban poverty in Vietnam – a view from complementary assessments Hoang Xuan Thanh, with Truong Tuan Anh and Dinh Thi Thu Phuong October 2013 i ABOUT THE AUTHORS Hoang Xuan Thanh, Senior Researcher, Ageless Consultants, Vietnam [email protected] Truong Tuan Anh, Researcher, Ageless Consultants, Vietnam [email protected] Dinh Thi Thu Phuong, Researcher, Ageless Consultants, Vietnam [email protected] Acknowledgements: This working paper has been funded entirely by UK aid from the UK Government. Its conclusions do not necessarily reflect the views of the UK Government. © IIED 2013 Human Settlements Group International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) 80-86 Gray’s Inn Road London WC1X 8NH, UK Tel: 44 20 3463 7399 Fax: 44 20 3514 9055 ISBN: 978-1-84369-959-0 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from http://pubs.iied.org/10633IIED.html Disclaimer: The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed here do not represent the views of any organisations that have provided institutional, organisational or financial support for the preparation of this paper. ii Contents Contents .............................................................................................................................................. -

Television Viewing Habits of Christians. Doctor of Philosophy

TELEVISION VIEWING HABITS OF CHRISTIANS Linda Jean Dutke, B.F.A, M.J. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2008 APPROVED: George Yancey, Major Professor Meta Carstarphen, Minor Professor Kevin Yoder, Committee Member Milan Zafirovski, Committee Member Mahmoud Sadri, Committee Member Dale Yeatts, Chair of the Department of Sociology Thomas Evenson, Dean of the College of Public Affairs and Community Service Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Dutke, Linda Jean, Television viewing habits of Christians. Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology), December 2008, 133 pp., 5 tables, references, 99 titles. This dissertation examines possible differences in media habits and tastes between Christians and non-Christians. The study utilizes data from singles Internet personal advertisements to determine whether or not Christians, especially those with high levels of religiosity or who may be part of the Christian Right, have different television viewing patterns. Three models were developed using multivariate data analysis and logistic regression to examine Christians’ television viewing habits regarding reality shows, soap operas, and news. The first model looks at the viewing habits of Christians, the second model examines the viewing habits of Christians attending religious services at least monthly, and the third model analyzes the viewing habits of Christians attending religious services at least monthly and having conservative political views. No significant differences were found in viewing habits between Christians and non-Christians for any of the three models. Although the results of this study cannot be generalized to Christians as a whole, they suggest that Christians in this sample might have adopted secular practices with regard to their television viewing habits. -

Popular, Elite and Mass Culture? the Spanish Zarzuela in Buenos Aires, 1890-1900

Popular, Elite and Mass Culture? The Spanish Zarzuela in Buenos Aires, 1890-1900 Kristen McCleary University of California, Los Angeles ecent works by historians of Latin American popular culture have focused on attempts by the elite classes to control, educate, or sophisticate the popular classes by defining their leisure time activities. Many of these studies take an "event-driven" approach to studying culture and tend to focus on public celebrations and rituals, such as festivals and parades, sporting events, and even funerals. A second trend has been for scholars to mine the rich cache of urban regulations during both the colonial and national eras in an attempt to mea- sure elite attitudes towards popular class activities. For example, Juan Pedro Viqueira Alban in Propriety and Permissiveness in Bourbon Mexico eloquently shows how the rules enacted from above tell more about the attitudes and beliefs of the elites than they do about those they would attempt to regulate. A third approach has been to examine the construction of national identity. Here scholarship explores the evolution of cultural practices, like the tango and samba, that developed in the popular sectors of society and eventually became co-opted and "sanitized" by the elites, who then claimed these activities as symbols of national identity.' The defining characteristic of recent popular culture studies is that they focus on popular culture as arising in opposition to elite culture and do not consider areas where elite and popular culture overlap. This approach is clearly relevant to his- torical studies that focus on those Latin American countries where a small group of elites rule over large predominantly rural and indigenous populations. -

The NFDA Cremation and Burial Report: Research, Statistics and Projections September 2014

The NFDA Cremation and Burial Report: Research, Statistics and Projections September 2014 A brand-new state-of-cremation publication featuring statistical information and in-depth analysis of the state of cremation today and what it means for you. The NFDA 2014 Cremation Report: Research, cost-effective for consumers. It is often followed by some Statistics and Projections type of memorialization event with family and friends – but frequently without the services of a funeral home. This results NFDA is the leading and largest funeral director in increased competition from the direct cremation (direct disposal)general sector. more cost-effective for consumers. It is often Theassociation NFDA in the 2014 world. Cremation We help our members Report: achieve followed by some type of memorialization event with Research,more by providing Statistics tools to manage, and a Projections successful family and friends – but frequently without the services of business. Thea funeralrising popularity home. This of cremation results in isincreased attributable competition to a number from NFDA is the leading and largest funeral director association of thfactors,e direct including cremation cost, (direct decreased disposal) household sector. discretionary in the world. We help our members achieve more by State of the Funeral Service Industry income, rising funeral expenses that continue to outpace providing tools to manage a successful business. inflationThe rising (Batesville, popularity 2013), of cremation environmental is attributable concerns, tofewer -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

Dolemite Is My Name

DOLEMITE IS MY NAME Written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski FINAL IN THE BLACK We hear Marvin Gaye's "What's Goin' On" playing softly. VOICE I ain't lying. People love me. INT. DOLPHIN'S - DAY CU of a beat-up record from the 1950s. On the paper cover is a VERY YOUNG Rudy, in a tuxedo. It says "Rudy Moore - BUGGY RIDE" RUDY You play this, folks gonna start hoppin' and squirmin', just like back in the day. A hand lifts the record up to the face of RUDY RAY MOORE, late '40s, black, sweet, determined. RUDY When I sang this on stage, I swear to God, people fainted! Ambulance man was picking them off the floor! When I had a gig, the promoter would warn the hospital: "Rudy's on tonight -- you're gonna be carrying bodies out of the motherfucking club!" We see that we are in a RADIO BOOTH. A sign blinks "On The Air." The DJ, ROJ, frowns at the record. ROJ "Buggy Ride"? RUDY Wasn't no small-time shit. ROJ GodDAMN, Rudy! That record's 1000 years old! I've got Marvin Gaye singin' "Let's Get It On"! I can't be playin' no "Buggy Ride." (beat) Look, I have 60 seconds. I have to cue the next tune. Hm! Rudy bites his lip and walks away. Roj tries to go back to his job. He reaches for a Sly Stone single -- when Rudy suddenly bounds back up. RUDY How about "Step It Up and Go"? That's a real catchy rhythm-and-blues number. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A life of worry : the cultural politics and phenomenology of anxiety in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4q05b9mq Authors Tran, Allen L. Tran, Allen L. Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO A life of worry: The cultural politics and phenomenology of anxiety in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Allen L. Tran Committee in charge: Professor Thomas J. Csordas, Chair Professor Suzanne A. Brenner Professor Yen Le Espiritu Professor Janis H. Jenkins Professor Edmund Malesky Professor Steven M. Parish 2012 ! The Dissertation of Allen L. Tran is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature page……...……………………………………………………………….……iii Table -

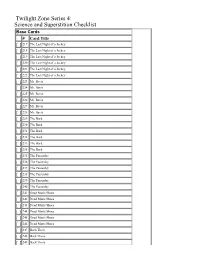

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

Uyghurs in China

Updated June 18, 2019 Uyghurs in China Uyghurs (also spelled “Uighurs”) are an ethnic group living intensive security measures aimed at combatting “terrorism, primarily in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region separatism and religious extremism.” According to PRC (XUAR) in the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC’s) official data, criminal arrests in Xinjiang increased by over northwest. Uyghurs speak a Turkic language and practice a 300% in the past five years compared to the previous five. moderate form of Sunni Islam. The XUAR, often referred to simply as Xinjiang (pronounced “SHIN-jyahng”), is a Two prominent Uyghurs serving life sentences for state provincial-level administrative region which comprises security crimes are Ilham Tohti (convicted in 2014), a about one-sixth of China’s total land area and borders eight Uyghur economics professor who had maintained a website countries. The region is rich in minerals, and has China’s related to Uyghur issues, and Gulmira Imin (convicted in largest coal and natural gas reserves and a fifth of the 2010), who had managed a Uyghur language website and country’s oil reserves. Beijing hopes to promote Xinjiang as participated in the 2009 demonstrations. a key link in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which includes Chinese-backed infrastructure projects and energy In tandem with a new national religious policy, also development in neighboring Central and South Asia. referred to as “Sinicization,” XUAR authorities have instituted measures to assimilate Uyghurs into Han Chinese society and reduce the influences of Uyghur, Islamic, and Arabic cultures and languages. The XUAR government enacted a law in 2017 that prohibits “expressions of extremification,” and placed restrictions, often imposed arbitrarily, upon face veils, beards and other grooming, some traditional Uyghur customs including wedding and funeral rituals, and halal food practices. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour.