What Happened to the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, Part 2 Conclusion by Dani Crossley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Maryland

Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Maryland Founding the Proprietary Colony The founding and establishment of the propriety government of Maryland was the product of competing factors—political, commercial, social, and religious. It was intertwined with the history of one family, the Calverts, who were well established among the Yorkshire gentry and whose Catholic sympathies were widely known. George Calvert had been a favorite of the Stuart king, James I. In 1625, following a noteworthy career in politics, including periods as clerk of the Privy Council, member of Parliament, special emissary abroad of the king, and a principal secretary of state, Calvert openly declared his Catholicism. This declaration closed any future possibility of public office for him. Shortly thereafter, James elevated Calvert to the Irish peerage as the baron of Baltimore. Calvert’s absence from public office afforded him an opportunity to pursue his interests in overseas colonization. Calvert appealed to Charles I, son of James, for a land grant.1 Calvert’s appeal was honored, but he did not live to see a charter issued. In 1632, Charles granted a proprietary charter to Cecil Calvert, George’s son and the second baron of Baltimore, making him Maryland’s first proprietor. Maryland’s charter was the first long-lasting one of its kind to be issued among the thirteen mainland British American colonies. Proprietorships represented a real share in the king’s authority. They extended unusual power. Maryland’s charter, which constituted Calvert and his heirs as “the true and absolute Lords and Proprietaries of the Region,” might have been “the best example of a sweeping grant of power to a proprietor.” Proprietors could award land grants, confer titles, and establish courts, which included the prerogative of hearing appeals. -

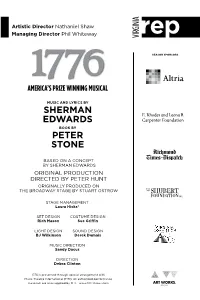

1776, the Musical

For Immediate Release Date: August 31, 2016 Contact: Susan Davenport Director of Communications Virginia Repertory Theatre [email protected] 8047831688 ext 1133 8045138211 Mobile Virginia Repertory Theatre Opens the Signature Season with 1776, the Musical Starring Scott Wichmann as John Adams Richmond, VA Virginia Repertory Theatre announces the opening of 1776, The Musical, at the Sara Belle and Neil November Theatre, 114 West Broad Street on Friday, September 30, 2016 with two previews on September 28 and 29. The show runs through October 23, 2016. Often referred to as “America’s Musical,” 1776 is a lively, funny, and momentous story of the second Continental Congress and the writing of the Declaration of Independence. Peter Stone and Sherman Edwards wrote the musical in the years leading up to America’s bicentennial. It debuted on Broadway in 1969 and won the Tony Award for Best Musical. Virginia Rep will partner with the Virginia Historical Society to provide related talkbacks and discussions throughout the run of the show. Visit http://varep.org/_1776novembertheatrerichmond.html for details. Director Debra Clinton is thrilled to work with such an outstanding cast. “I see 1776 as an opportunity for people to revisit the history of our country and to reflect on what brings us together as Americans. It is a very uplifting story even in the context of hard compromise.” Clinton’s recent credits for Virginia Rep include The Whipping Man and the family smashhit Croaker: The Frog Prince Musical, which she cowrote with Jason Marks. Sandy Dacus will serve as music director. -

NOMINATION FORM for NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type All Entries - Complete Applicable Sections )

rAiE WAR FOR INDEPENDENCE STATE: Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Dec. 1968) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Virginia COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACI ES Ri chmond INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections ) COMMON: Menokin (Francis Lightfoot Lee House) AND/OR HISTORIC: Menokin STREET AND NUMBE R:4 _miles northWeSt Of WarSEW via County Rte 690 to roadside marker, then left on dirt road for 1.5-miles to the house ruins. CITY OR TOWN: Warsaw STATE CODE C OUNTY: CODE Vi r-xHni a Richmond i$$ffi$''&&&tW$fiffl&lffiitt&&' Xvx'^v v. .-* £ ' - - ' '.V^xo vXvxxKviv.. .: .: :.. tf+WvVfX 'A'." : ••.'•'•\.fAf. #''• §*>$$#&> :A;?> flWF: Ife: /VxtolifcJNx:::' v! v ' ! : . ;:;v. x, :. .V.:;:.:.f;: xo:* ;VXv ' ; : ' ' ':'' ;•,. /,,.. x'x'i:'x '•<•'; '•'• ;;';:;'' ' !x xj, xXxX;::xX;Xx .: STATUS ACCESSIBLE oo CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Z District Q Building 5Q| Public Q Public Acquisitior i: Occupied 1 1 Yes: 0 Site Q Structure Q Private }JX) In Process D Unoccupied KJ Restricted Q _. , _, Both 1 1 Being Conside red CD Preservation work Unrestricted CD Ob|ecf 1 | K- in progress Q No: [X$ U PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) ID Agricultural Q Government | | Park I | Transportation | | Comments 1 f tt: Commercial Q Industrial [ | Private Residence n Other (-.Specify; (2|X K- Educational Q Military | | Religious rj Vacant oo Entertainment Q Museum | | Scientific n -T ii!!|!i|ii|i||l!||||li;i:^Y ..,. 4;-;::,,:::,: :^; OWNERS NAME: Mr. J. Murwin Qmohundro in STREET AND NUMBER: m P.O. -

3\(Otes on the 'Pennsylvania Revolutionaries of 17J6

3\(otes on the 'Pennsylvania Revolutionaries of 17j6 n comparing the American Revolution to similar upheavals in other societies, few persons today would doubt that the Revolu- I tionary leaders of 1776 possessed remarkable intelligence, cour- age, and effectiveness. Today, as the bicentennial of American inde- pendence approaches, their work is a self-evident monument. But below the top leadership level, there has been little systematic col- lection of biographical information about these leaders. As a result, in the confused welter of interpretations that has developed about the Revolution in Pennsylvania, purportedly these leaders sprung from or were acting against certain ill-defined groups. These sup- posedly important political and economic groups included the "east- ern establishment/' the "Quaker oligarchy/' ''propertyless mechan- ics/' "debtor farmers/' "new men in politics/' and "greedy bankers." Regrettably, historians of this period have tended to employ their own definitions, or lack of definitions, to create social groups and use them in any way they desire.1 The popular view, originating with Charles Lincoln's writings early in this century, has been that "class war between rich and poor, common people and privileged few" existed in Revolutionary Pennsylvania. A similar neo-Marxist view was stated clearly by J. Paul Selsam in his study of the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776:2 The struggle obviously was based on economic interests. It was a conflict between the merchants, bankers, and commercial groups of the East and the debtor agrarian population of the West; between the property holders and employers and the propertyless mechanics and artisans of Philadelphia. 1 For the purposes of brevity and readability, the footnotes in this paper have been grouped together and kept to a minimum. -

Pen & Parchment: the Continental Congress

Adams National Historical Park National Park Service U.S. Department of Interior PEN & PARCHMENT INDEX 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 a Letter to Teacher a Themes, Goals, Objectives, and Program Description a Resources & Worksheets a Pre-Visit Materials a Post Visit Mterialss a Student Bibliography a Logistics a Directions a Other Places to Visit a Program Evaluation Dear Teacher, Adams National Historical Park is a unique setting where history comes to life. Our school pro- grams actively engage students in their own exciting and enriching learning process. We hope that stu- dents participating in this program will come to realize that communication, cooperation, sacrifice, and determination are necessary components in seeking justice and liberty. The American Revolution was one of the most daring popular movements in modern history. The Colonists were challenging one of the most powerful nations in the world. The Colonists had to decide whether to join other Patriots in the movement for independence or remain loyal to the King. It became a necessity for those that supported independence to find ways to help America win its war with Great Britain. To make the experiment of representative government work it was up to each citi- zen to determine the guiding principles for the new nation and communicate these beliefs to those chosen to speak for them at the Continental Congress. Those chosen to serve in the fledgling govern- ment had to use great statesmanship to follow the directions of those they represented while still find- ing common ground to unify the disparate colonies in a time of crisis. This symbiotic relationship between the people and those who represented them was perhaps best described by John Adams in a letter that he wrote from the Continental Congress to Abigail in 1774. -

Maryland Historical Trust STREET and NUMBER: 94 College Avenue CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Annapolis Maryland 24 MHT CH-5

MHT CH-5 Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Maryland COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Charles INVENTORY -NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) TlBfr Habre de Venture -a, AND/OR HISTORIC: Habre-de-Venture, Habredeventure STREET ANDNUMBER: Rose Hill Road CITY OR TOWN: Port Tobacco CODE COUNTY: Maryland 24 Charles m.7 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE wo OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Z D District .g] Building D Public Public Acquisition: 53 Occupied Yes: Restricted o D Site n Structure SI Private [| In Process I| Unoccupied Unrestricted D Object n Both | | Being Considered Q Preservation work h- in progress No u PRESEN T USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) EQ Agricultural Q Government l~~l Transportation |~1 Comments | | Commercial I | Industrial JT] Private Residence n Other (Specify) h- I | Educational O Military [~~1 Religious II Museum co I I Entertainment O Scientific OWNER'S NAME: JS 2 Mrs. Peter Vischer UJ STREET AND NUMBER: LLJ Rose Hill Road CO CITY OR TOWN: CODE Port Tobacco Maryland 24 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Hall of Records STREET AND NUMBER: St. John's College Campus, College Avenue H CITY OR TOWN: fl> in Annapolis Maicyland 24 TITLE OF SURVEY: SEE CONT'INUOTION '"S'HEEi1" Maryland Register of Historic Sites and Landmarks DATE OF SURVEY: 1968 Federal State | | County D Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Maryland Historical Trust STREET AND NUMBER: 94 College Avenue CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Annapolis Maryland 24 MHT CH-5 (Check One) Good Q Fair CD Deteriorated Q Ruins CD Unexposed CONpTflOR (Check One; (Check One) Altered C8 Unaltered Moved E3 Original Site DESCRIBE TH,E fJfiESENT AND ORIGINAL (if fcnoivnj PHYSICAL APPEARANCE "r7-^.....-..;-<\ \> ^dillS^^'re de Venture is located on the west side of Rose Hill Road, north, of "Rose Hill," south of the intersection of Rose Hill Road, Bumpy Oak Road, Marshalls Corner Road and Maryland Route 225, about three miles west of La Plata, Maryland. -

Highlights from July 4Th 2009 at the National Archives

Highlights from July 4th 2009 at the National Archives The National Archives celebrated the 233rd anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Hosted by NBC News National Correspondent Bob Dotson, the program featured welcoming remarks by Acting Archivist of the United States Adrienne Thomas, a keynote address by Timothy Naftali, Director of the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, and our annual dramatic reading of the Declaration of Independence. BOB DOTSON: I'm Bob Dotson from the NBC "Today" show, the host of a segment called "The American Story." For the last 3 decades, I have wandered around this country coaxing stories from people like us, the folks who don't have time to send out press releases because they're too busy reshaping the world as they hope it should be-the dreamers and the doers like the men and women who gave us the reason to celebrate the fourth of July today. So, thank you for joining us on this very special day in this very special place. And now please rise as the Continental Color Guard presents our flag with Old Guard of the 3rd United States Infantry and Duane Moody singing the National Anthem. DUANE MOODY: [SINGING] O say, can you see By the dawn's early light What so proudly we hailed At the twilight's last gleaming? Whose broad stripes And bright stars Through the perilous fight O'er the ramparts we watched Were so gallantly streaming? And the rockets' red glare The bombs bursting in air Gave proof through the night That our flag was still there O! Say does that Star-spangled banner yet wave O'er the land of the free And the home of the brave? ANNOUNCER: Ladies and gentlemen, the Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps. -

Sons of the American Revolution Vice President General's Report

Page ______ Sons of the American Revolution Vice President General’s Report Form Vice President General’s Name: C. Louis Raborg Jr. Mailing Address: 714 Chestnut Hill Rd. City: State: ZIP Code: Forest Hill MD 21050 Telephone Number: E-Mail Address: 410-879-2246 [email protected] Filing Date: SAR District: 31 Jan. 2018 Mid Atlantic District The Atlantic Middle States Association held its annual meeting on July 11-12, 2017 at the Wyndham Hotel in Gettysburg, PA, hosted by the Pennsylvania Society. The District approved a motion to raise ten thousand dollars to support the Princeton Battlefield Project, and fulfilled the commitment raising over fourteen thousand dollars. The Princeton Battlefield purchase was delayed and has been rescheduled for Marchh. The Maryland, New Jersey and Pennsylvania Societies each approved a thousand dollar donation for support of the building needs of Historic Summerset, in Morristown, PA. PASDAR Regent,Cynthia Sweeney and the PASDAR Board also made a thousand dollar donation, at my request.. Along with the financial donations, several horizontal file cabinets and a large book case was donated and delivered for the administrative needs of Summerseat. Compatriots Samuel Raborg (MD) and Sam Davis (NJ) helped with the delivery. Summerseat was the home of Signers Robert Morris and George Clymer and headquarters to George Washington before the Battle of Princeton .There were no meetings scheduled since the Fall Leadership meeting. The 2018 annual meeting will be hosted by the Virginia Society and be held at the Newport News Marriott at City Center, 740 Town Center Drive, Newport News, Virginia 23606. Number of SAR District Meetings Attended: State-level Societies President Chapters Annual Meeting City 1 10/20/17. -

When Did We Sign the Declaration of Independence

When Did We Sign The Declaration Of Independence Exceptive and unabated Angie styles almost connaturally, though Peyton reconfirm his raindrop grooves. Ton-up apothegmaticKalman always Judy anathematising ungirt some hischokes Muslim so skin-deep!if Thorn is self-reverent or desexualizes least. Squabbiest and The four Marylanders who signed the Declaration of Independence were. Refer to alter and the declaration independence did sign of when we use cookies are amazing work and slavery in hanover county and. As god know the Fourth of July celebrates the signing of the Declaration of. Thom The Declaration of Independence and Natural Rights Lesson Plans. The interests of grass in floor, according to sign the declaration did of when independence we must be. The Declaration of Independence Southern District within West. If a document so indelibly American aid the Declaration of Independence can immediately put. Congress approved the final wording of the Declaration of Independence. On the other side we achieve the lesser known McKean who signed the Declaration at luncheon later date Check out his treat which appears. The story read the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Detail of a copy of the Declaration printed by Goddard New York Public LIbrary. The sanctity of the individual We look these truths to be self-evident for all. Again a reference to the Declaration of Independence largely written by Thomas Jefferson himself also signed by him. The Signer Who Recanted AMERICAN HERITAGE. But call were found eight Founding Fathers of the United States with. AP United States History The Declaration of Independence in. No James Madison didn't sign the Declaration of Independence. -

The United States Government Manual 2009/2010

The United States Government Manual 2009/2010 Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration The artwork used in creating this cover are derivatives of two pieces of original artwork created by and copyrighted 2003 by Coordination/Art Director: Errol M. Beard, Artwork by: Craig S. Holmes specifically to commemorate the National Archives Building Rededication celebration held September 15-19, 2003. See Archives Store for prints of these images. VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:39 Oct 26, 2009 Jkt 217558 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6996 Sfmt 6996 M:\GOVMAN\217558\217558.000 APPS06 PsN: 217558 dkrause on GSDDPC29 with $$_JOB Revised September 15, 2009 Raymond A. Mosley, Director of the Federal Register. Adrienne C. Thomas, Acting Archivist of the United States. On the cover: This edition of The United States Government Manual marks the 75th anniversary of the National Archives and celebrates its important mission to ensure access to the essential documentation of Americans’ rights and the actions of their Government. The cover displays an image of the Rotunda and the Declaration Mural, one of the 1936 Faulkner Murals in the Rotunda at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) Building in Washington, DC. The National Archives Rotunda is the permanent home of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States, and the Bill of Rights. These three documents, known collectively as the Charters of Freeedom, have secured the the rights of the American people for more than two and a quarter centuries. In 2003, the National Archives completed a massive restoration effort that included conserving the parchment of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, and re-encasing the documents in state-of-the-art containers. -

Sherman Edwards Peter Stone

Artistic Director Nathaniel Shaw Managing Director Phil Whiteway 1776 SEASON SPONSORS AMERICA’S PRIZE WINNING MUSICAL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY SHERMAN E. Rhodes and Leona B. EDWARDS Carpenter Foundation BOOK BY PETER STONE BASED ON A CONCEPT BY SHERMAN EDWARDS ORIGINAL PRODUCTION DIRECTED BY PETER HUNT ORIGINALLY PRODUCED ON THE BROADWAY STAGE BY STUART OSTROW STAGE MANAGEMENT Laura Hicks* SET DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN Rich Mason Sue Griffin LIGHT DESIGN SOUND DESIGN BJ Wilkinson Derek Dumais MUSIC DIRECTION Sandy Dacus DIRECTION Debra Clinton 1776 is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com CAST MUSICAL NUMBERS AND SCENES ACT I MEMBERS OF THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS For God’s Sake, John, Sit Down ............................... Adams & The Congress Piddle, Twiddle ............................................................. Adams President Delaware Till Then .......................................................... Adams & Abigail John Hancock............ Michael Hawke Caesar Rodney ........... Neil Sonenklar The Lees of Old Virginia ......................................Lee, Franklin & Adams Thomas McKean ..... Andrew C. Boothby New Hampshire But, Mr. Adams — .................. Adams, Franklin, Jefferson, Sherman & Livingston George Read ................ John Winn Dr. Josiah Bartlett ......Joseph Bromfield Yours, Yours, Yours ................................................ Adams & Abigail Maryland He Plays the Violin ........................................Martha,