Freshwater Snail Biodiversity and Conservation Paul D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Fws–R4–Es–2014–N167; Fxes11130400000c2–145–Ff04e00000]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4450/fws-r4-es-2014-n167-fxes11130400000c2-145-ff04e00000-614450.webp)

Fws–R4–Es–2014–N167; Fxes11130400000c2–145–Ff04e00000]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 11/06/2014 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2014-26362, and on FDsys.gov Billing Code 4310–55 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service [FWS–R4–ES–2014–N167; FXES11130400000C2–145–FF04E00000] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Final Recovery Plan for Georgia Pigtoe Mussel, Interrupted Rocksnail, and Rough Hornsnail AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice of availability. SUMMARY: We, the Fish and Wildlife Service, announce the availability of the final recovery plan for the endangered Georgia pigtoe mussel, interrupted rocksnail, and rough hornsnail. The final recovery plan includes specific recovery objectives and criteria the interrupted rocksnail and rough hornsnail would have to meet in order for us to downlist them to threatened status under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act). Recovery criteria for the Georgia pigtoe will be developed after we complete critical recovery actions and gain a greater understanding of the species. ADDRESSES: You may obtain a copy of the recovery plan by contacting Jeff Powell at the Alabama Field Office, by U.S. mail at U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alabama Field Office, 1208–B Main Street, Daphne, AL 36526, or by telephone at (251) 441–5858; or by visiting our recovery plan website at http://www.fws.gov/endangered/species/recovery-plans.html. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Jeff Powell (see ADDRESSES above). SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Introduction We listed the Georgia pigtoe mussel (Pleurobema hanleyianum), interrupted rocksnail (Leptoxis foremani), and rough hornsnail (Pleurocera foremani) as endangered species under the Act (16 U.S.C. -

2010 Federal Register, 75 FR 6613; Centralized Library: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 27 / Wednesday, February 10, 2010 / Proposed Rules 6613 This document does not contain the Commission’s Secretary, Office of availability of the draft economic proposed information collection the Secretary, Federal Communications analysis for the proposed designation of requirements subject to the Paperwork Commission. critical habitat for 3 mollusks, Georgia Reduction Act of 1995, Public Law 104– • The Commission’s contractor will pigtoe mussel (Pleurobema 13. In addition, therefore, it does not receive hand–delivered or messenger– hanleyianum), interrupted rocksnail contain any proposed information delivered paper filings for the (Leptoxis foremani), and rough collection burden ’’for small business Commission’s Secretary at 236 hornsnail (Pleurocera foremani), under concerns with fewer than 25 Massachusetts Avenue, NE, Suite 110, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as employees,’’ pursuant to the Small Washington, DC 20002. The filing hours amended (Act). We also announce the Business Paperwork Relief Act of 2002, at this location are 8:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. availability of a draft economic analysis Public Law 107–198, see 44 U.S.C. All hand deliveries must be held (DEA) and an amended required 3506(c)(4). together with rubber bands or fasteners. determinations section of the proposal. Provisions of the Regulatory Any envelope must be disposed of We are reopening the comment period Flexibility Act of 1980 does not apply before entering the building. for an additional 30 days to allow all to this proceeding. • Commercial overnight mail (other interested parties an opportunity to Pursuant to sections 1.415 and 1.419 than U.S. -

Permitting Update in Potential Rough Hornsnail Habitat

Permitting Update in Potential Rough Hornsnail Habitat on Lake Mitchell & Lay Lake The rough hornsnail (Pleurocera foremani) What does this mean? The sensitive area (RHS) is a species of snail that is federally of Lay Lake has not changed. However, listed under the Endangered Species Act additional shoreline on Lake Mitchell has been (ESA). It was identified by federal authorities designated as sensitive and subject to the during the relicensing of the Coosa River measures that are protective of the RHS. If it Hydroelectric Project and is located along is determined that the proposed activity could certain stretches of the Coosa River and impact the RHS or its habitat, the applicant its tributaries. Specifically, the species is will be required to conduct a survey & found in the upper reaches of Lay Lake and relocation of the RHS by a qualified contractor significant portions of Lake Mitchell. In 2016, prior to beginning any project work. Alabama Power Company (APC) and the U. Applicants can expect a lengthier process for S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) came permit approval and additional expense for to an agreement on measures that must be the survey and relocation. No permits will taken to protect the snail. These measures be issued by APC’s Shoreline Management apply to certain lakeshore activities such in sensitive areas on Lake Mitchell or Lay as dredging; construction of sea walls; Lake for activities potentially impacting the installation of rip rap; and construction RHS without the appropriate review and and maintenance of piers, boathouses, and USACE authorization. If the applicant decides boat ramps where they pose a risk to the to proceed without a permit, the shoreline snail and/or its habitat. -

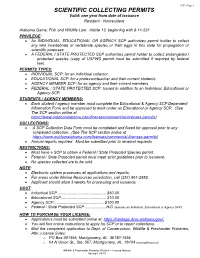

SCIENTIFIC COLLECTING PERMITS Valid: One Year from Date of Issuance Resident - Nonresident

SCP – Page 1 SCIENTIFIC COLLECTING PERMITS Valid: one year from date of issuance Resident - Nonresident Alabama Game, Fish and Wildlife Law; Article 12; beginning with 9-11-231 PRIVILEGE: • An INDIVIDUAL, EDUCATIONAL OR AGENCY SCP authorizes permit holder to collect any wild invertebrate or vertebrate species or their eggs in this state for propagation or scientific purposes. • A FEDERAL / STATE PROTECTED SCP authorizes permit holder to collect endangered / protected species (copy of USFWS permit must be submitted if required by federal law). PERMITS TYPES: • INDIVIDUAL SCP: for an individual collector. • EDUCATIONAL SCP: for a professor/teacher and their current students. • AGENCY MEMBER SCP: for an agency and their current members. • FEDERAL / STATE PROTECTED SCP: Issued in addition to an Individual, Educational or Agency SCP. STUDENTS / AGENCY MEMBERS: • Each student / agency member must complete the Educational & Agency SCP Dependent Information Form and be approved to work under an Educational or Agency SCP. (See The SCP section online at https://www.outdooralabama.com/licenses/commercial-licenses-permits) COLLECTIONS: • A SCP Collection Data Form must be completed and faxed for approval prior to any scheduled collection. (See The SCP section online at https://www.outdooralabama.com/licenses/commercial-licenses-permits) • Annual reports required. Must be submitted prior to renewal requests. RESTRICTIONS: • Must have a SCP to obtain a Federal / State Protected Species permit. • Federal / State Protected permit must meet strict guidelines prior to issuance. • No species collected are to be sold. NOTE: • Electronic system processes all applications and reports. • For areas under Marine Resources jurisdiction, call (251) 861-2882. • Applicant should allow 3 weeks for processing and issuance. -

Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service

Monday, November 9, 2009 Part III Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Native Species That Are Candidates for Listing as Endangered or Threatened; Annual Notice of Findings on Resubmitted Petitions; Annual Description of Progress on Listing Actions; Proposed Rule VerDate Nov<24>2008 17:08 Nov 06, 2009 Jkt 220001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\09NOP3.SGM 09NOP3 jlentini on DSKJ8SOYB1PROD with PROPOSALS3 57804 Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 215 / Monday, November 9, 2009 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR October 1, 2008, through September 30, for public inspection by appointment, 2009. during normal business hours, at the Fish and Wildlife Service We request additional status appropriate Regional Office listed below information that may be available for in under Request for Information in 50 CFR Part 17 the 249 candidate species identified in SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. General [Docket No. FWS-R9-ES-2009-0075; MO- this CNOR. information we receive will be available 9221050083–B2] DATES: We will accept information on at the Branch of Candidate this Candidate Notice of Review at any Conservation, Arlington, VA (see Endangered and Threatened Wildlife time. address above). and Plants; Review of Native Species ADDRESSES: This notice is available on Candidate Notice of Review That Are Candidates for Listing as the Internet at http:// Endangered or Threatened; Annual www.regulations.gov, and http:// Background Notice of Findings on Resubmitted endangered.fws.gov/candidates/ The Endangered Species Act of 1973, Petitions; Annual Description of index.html. -

Conservation Status of Freshwater Gastropods of Canada and the United States Paul D

This article was downloaded by: [69.144.7.122] On: 24 July 2013, At: 12:35 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Fisheries Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ufsh20 Conservation Status of Freshwater Gastropods of Canada and the United States Paul D. Johnson a , Arthur E. Bogan b , Kenneth M. Brown c , Noel M. Burkhead d , James R. Cordeiro e o , Jeffrey T. Garner f , Paul D. Hartfield g , Dwayne A. W. Lepitzki h , Gerry L. Mackie i , Eva Pip j , Thomas A. Tarpley k , Jeremy S. Tiemann l , Nathan V. Whelan m & Ellen E. Strong n a Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (ADCNR) , 2200 Highway 175, Marion , AL , 36756-5769 E-mail: b North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences , Raleigh , NC c Louisiana State University , Baton Rouge , LA d United States Geological Survey, Southeast Ecological Science Center , Gainesville , FL e University of Massachusetts at Boston , Boston , Massachusetts f Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources , Florence , AL g U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service , Jackson , MS h Wildlife Systems Research , Banff , Alberta , Canada i University of Guelph, Water Systems Analysts , Guelph , Ontario , Canada j University of Winnipeg , Winnipeg , Manitoba , Canada k Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources , Marion , AL l Illinois Natural History Survey , Champaign , IL m University of Alabama , Tuscaloosa , AL n Smithsonian Institution, Department of Invertebrate Zoology , Washington , DC o Nature-Serve , Boston , MA Published online: 14 Jun 2013. -

American Fisheries Society • JUNE 2013

VOL 38 NO 6 FisheriesAmerican Fisheries Society • www.fisheries.org JUNE 2013 All Things Aquaculture Habitat Connections Hobnobbing Boondoggles? Freshwater Gastropod Status Assessment Effects of Anthropogenic Chemicals 03632415(2013)38(6) Biology and Management of Inland Striped Bass and Hybrid Striped Bass James S. Bulak, Charles C. Coutant, and James A. Rice, editors The book provides a first-ever, comprehensive overview of the biology and management of striped bass and hybrid striped bass in the inland waters of the United States. The book’s 34 chapters are divided into nine major sections: History, Habitat, Growth and Condition, Population and Harvest Evaluation, Stocking Evaluations, Natural Reproduction, Harvest Regulations, Conflicts, and Economics. A concluding chapter discusses challenges and opportunities currently facing these fisheries. This compendium will serve as a single source reference for those who manage or are interested in inland striped bass or hybrid striped bass fisheries. Fishery managers and students will benefit from this up-to-date overview of priority topics and techniques. Serious anglers will benefit from the extensive information on the biology and behavior of these popular sport fishes. 588 pages, index, hardcover List price: $79.00 AFS Member price: $55.00 Item Number: 540.80C Published May 2013 TO ORDER: Online: fisheries.org/ bookstore American Fisheries Society c/o Books International P.O. Box 605 Herndon, VA 20172 Phone: 703-661-1570 Fax: 703-996-1010 Fisheries VOL 38 NO 6 JUNE 2013 Contents COLUMNS President’s Hook 245 Scientific Meetings are Essential If our society considers student participation in our major meetings as a high priority, why are federal and state agen- cies inhibiting attendance by their fisheries professionals at these very same meetings, deeming them non-essential? A colony of the federally threatened Tulotoma attached to the John Boreman—AFS President underside of a small boulder from lower Choccolocco Creek, 262 Talladega County, Alabama. -

Alabama Inventory List

Alabama Inventory List The Rare, Threatened, & Endangered Plants & Animals of Alabama Alabama Natural August 2015 Heritage Program® TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 1 CHANGES FROM ALNHP TRACKING LIST OF OCTOBER 2012 ............................................... 3 DEFINITION OF HERITAGE RANKS ................................................................................................ 6 DEFINITIONS OF FEDERAL & STATE LISTED SPECIES STATUS ........................................... 8 VERTEBRATES ...................................................................................................................................... 10 Birds....................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Mammals ............................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Reptiles .................................................................................................................................................................................. 18 Lizards, Snakes, and Amphisbaenas .................................................................................................................................. 18 Turtles and Tortoises ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Conservation, Life History and Systematics of Leptoxis Rafinesque

CONSERVATION, LIFE HISTORY AND SYSTEMATICS OF LEPTOXIS RAFINESQUE 1819 (GASTROPODA: CERITHIOIDEA: PLEUROCERIDAE) by NATHAN VINCENT WHELAN PHILLIP M. HARRIS, COMMITTEE CHAIR DANIEL L. GRAF JUAN M. LOPEZ-BAUTISTA ALEX D. HURYN PAUL D. JOHNSON A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Biological Sciences in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2013 Copyright Nathan Vincent Whelan 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Freshwater gastropods of the family Pleuroceridae are incredibly important to the health of freshwater ecosystems in the southeastern United States. Surprisingly, however, they are one of the most understudied groups of mollusks in North America. Recent data suggest that pleurocerids have an imperilment rate of 79% and many species are under immediate threat of extinction. As such, the time is now to better understand their biology, taxonomy, and phylogeny. Any study that wishes to understand a species group like pleurocerids must start with extensive field work and taxon sampling. As a part of that endeavor I rediscovered Leptoxis compacta, a snail that had not been collected live in 76 years. In chapter two, I report on this discovery and I propose a captive propagation plan and potential reintroduction sites for L. compacta in an attempt to prevent its extinction. In chapter three, I explore the often reported species level polyphyly on mitochondrial gene trees for gastropods in the family Pleuroceridae and its sister family Semisulcospiridae. Explanations for this paraphyly have ranged from unsatisfying (e.g. that species-level polyphyly is caused by historical introgression) to absurd (e.g. -

Endangered Species Is These 12–Month Findings in the Federal Species Information Warranted, but Precluded by Other Register

Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 66 / Wednesday, April 7, 2010 / Proposed Rules 17667 biphenyls (PCBs), Reporting and SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: in the November 26, 1996, Recovery recordkeeping requirements. Plan for the Sacramento–San Joaquin Background Dated: March 31, 2010. Delta Native Fishes (Service 1996, pp. 1- Section 4(b)(3)(A) of the Endangered Lisa P. Jackson, 195). We completed a 5–year status Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act) review of the delta smelt on March 31, Administrator. (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.) requires that, for 2004 (Service 2004, pp. 1-50). [FR Doc. 2010–7751 Filed 4–6–10; 8:45 am] any petition to add a species to, remove On March 9, 2006, we received a BILLING CODE 6560–50–S a species from, or reclassify a species on petition to reclassify the listing status of one of the Lists of Endangered and the delta smelt, a threatened species, to Threatened Wildlife and Plants, we first endangered on an emergency basis. We DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR make a determination whether the sent a letter to the petitioners dated June petition presents substantial scientific 20, 2006, stating that we would not be Fish and Wildlife Service or commercial information indicating able to address their petition at that time that the petitioned action may be because further action on the petition 50 CFR Part 17 warranted. To the maximum extent was precluded by court orders and practicable, we make this determination [Docket No. FWS-R8-ES-2008-0067] settlement agreements for other listing within 90 days of receipt of the petition, [MO 92210-0-0008-B2] actions that required us to use nearly all and publish the finding promptly in the of our listing funds for fiscal year 2006. -

1 Current and Selected Bibliographies on Benthic

1 ================================================================================== CURRENT AND SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHIES ON BENTHIC BIOLOGY – 2014 [published in May 2016] -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- FOREWORD. “Current and Selected Bibliographies on Benthic Biology” is published annually for the members of the Society for Freshwater Science (SFS) (formerly, the Midwest Benthological Society [MBS, 1953-1975] then the North American Benthological Society [NABS, 1975-2011]). This compilation summarizes titles of articles published during the year (2014). Additionally, pertinent titles of articles published prior to 2014 also have been included if they had not been cited in previous reviews, or to correct errors in previous annual bibliographies, and authors of several sections have also included citations for recent (2015–) publications. I extend my appreciation to past and present members of the MBS, NABS and SFS Literature Review and Publications Committees and the Society presidents and treasurer Mike Swift for their support (including some funds to compensate hourly assistance to Wetzel during the editing of literature contributions from section compilers), to librarians Elizabeth Wohlgemuth (Illinois Natural History Survey) and Susan Braxton (Prairie Research Institute) for their assistance in accessing journals, other publications, bibliographic search engines and abstracting resources, and rare publications critical to the -

Rediscovery of Leptoxis Compacta (Anthony, 1854) (Gastropoda: Cerithioidea: Pleuroceridae)

Rediscovery of Leptoxis compacta (Anthony, 1854) (Gastropoda: Cerithioidea: Pleuroceridae) Nathan V. Whelan1*, Paul D. Johnson2, Phil M. Harris1 1 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, United States of America, 2 Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Marion, Alabama, United States of America Abstract The Mobile River Basin is a hotspot of molluscan endemism, but anthropogenic activities have caused at least 47 molluscan extinctions, 37 of which were gastropods, in the last century. Nine of these suspected extinctions were in the freshwater gastropod genus Leptoxis (Cerithioidea: Pleuroceridae). Leptoxis compacta, a Cahaba River endemic, has not been collected for .70 years and was formally declared extinct in 2000. Such gastropod extinctions underscore the imperilment of freshwater resources and the current biodiversity crisis in the Mobile River Basin. During a May 2011 gastropod survey of the Cahaba River in central Alabama, USA, L. compacta was rediscovered. The identification of snails collected was confirmed through conchological comparisons to the L. compacta lectotype, museum records, and radulae morphology of historically collected L. compacta. Through observations of L. compacta in captivity, we document for the first time that the species lays eggs in short, single lines. Leptoxis compacta is restricted to a single location in the Cahaba River, and is highly susceptible to a single catastrophic extinction event. As such, the species deserves immediate conservation attention. Artificial propagation and reintroduction of L. compacta into its native range may be a viable recovery strategy to prevent extinction from a single perturbation event. Citation: Whelan NV, Johnson PD, Harris PM (2012) Rediscovery of Leptoxis compacta (Anthony, 1854) (Gastropoda: Cerithioidea: Pleuroceridae).