The Grand Game: Articles Mainly on Issues Affecting the Horn of Africa Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Puzzle of International Decision-Making an Integrated Comparative Study on Intervention

Södertörns Högskola Filip Holm Internationella Relationer C 2014 C-Uppsats, 15 poäng The puzzle of international decision-making An integrated comparative study on intervention By Filip Holm Map of the Sudan region (Enough Project [image] <http://www.enoughproject.org/conflicts/sudans> Accessed September 1, 2014) Map of Libya (GeographyIQ [image] http://www.geographyiq.com/countries/ly/Libya_map_flag_geography.htm Accessed December 1, 2014) Abstract “The puzzle of international decision-making” An integrated comparative study on intervention This is a study that aims to look at the violence occurring in Sudan and Libya in 2011. It asks the question why there was an intervention in the latter case but not the former. The analysis will use an integrated theoretical framework, looking at national interests, power balance and international norms to explain the behavior and decision-making of states in these particular cases. The fact that so little has been done or said about the conflict in Sudan is troubling, and deserves an explanation, especially considering the very different reaction to similar situations like Libya at the time. This study uses a comparative method to map the differences and similarities between the two cases using both statistical numbers and facts, as well as a content analysis to examine the discourse and media coverage on the two conflicts. The analysis may seem very broad and complex, but the same can be said about world politics in general. It is a very complex thing, and sometimes a complex explanation is required. Very rarely is there just one answer to a question like this, but many different perspectives that are often equally legitimate and important to consider. -

Sudan: Colonialism, Independence, and Conflict

Sudan: Colonialism, Independence, and Conflict Overview Students will analyze the impact of colonization on Sudan including regional divisions, independence movements, and conflict. Students will understand the various economic, political, and societal factors that have led to wars in the region. Students will also learn that these conflicts have led to migration out of Sudan, exploring cultural and artistic production of Sudanese people in the diaspora. Students will learn that the effects of decolonization and ethnic conflict have been a push factor for African migration in the new wave of diaspora. Essential/Compelling Question(s) How has the legacy of colonization and imperialism impacted Sudan? How has conflict in Sudan affected the country’s politics, economy, and society? How are human rights affected in times of conflict? Grade(s) 9-12 Subject(s) World History North Carolina Essential Standards WH.8: Analyze global interdependence and shifts in power in terms of political, economic, social and environmental changes and conflicts since the last half of the twentieth century. WH.H.8.3: Analyze the "new" balance of power and the search for peace and stability in terms of how each has influenced global interactions since the last half of the twentieth century (e.g., post WWII, Post Cold War, 1990s Globalization, New World Order, Global Achievements and Innovations). WH.8.6: Explain how liberal democracy, private enterprise and human rights movements have reshaped political, economic and social life in Africa, Asia, Latin America, Europe, the Soviet Union and the United States (e.g., U.N. Declaration of Human Rights, end of Cold War, apartheid, perestroika, glasnost, etc.). -

Legal Empowerment-Participants Handbook-2016.Indd

Legal Empowerment Leadership Course 10–14 October 2016 l Budapest, Hungary Participants Booklet Welcome .................................................................. 2 Course methodology .................................................. 4 Course schedule ........................................................ 8 Program ........................................................................ 10 Arrival .................................................................. 10 Dinner reception ................................................... 11 Course venue ........................................................ 12 Farewell reception ................................................. 13 Logistical information ................................................ 14 Course venue .................................................... 14 Meals .............................................................. 14 Eating out ............................................................ 14 Smoking ........................................................... 15 of Contents Table Internet and WiFi .............................................. 15 Social media..................................................... 15 Medical care ..................................................... 16 Weather and clothing ......................................... 16 Course coordinators ........................................... 17 A note on Hungary ............................................. 18 Useful Hungarian phrases ...................................... 21 Reading -

ICONEA Conference 2012: Programme

ICONEA Conference 2012: AEROPHONES IN THE ANCIENT WORLD: NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST, EGYPT AND THE MEDITERRANEAN NOVEMBER 22, 23 and 24, 2012 UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Programme Thursday 22 November 1400: Registration 1430: Speeches: Paul Archbold, Irving Finkel and Richard Dumbrill Chair: Irving Finkel 1445: Richard Dumbrill When is a pipe not a pipe? I shall investigate so-called pipes, flutes, etc., from Neanderthalians, Cro-Magnons, etc. and up to to the literate Ancient Mesopotamians and later Mediterraneans. 1545: Tea/coffee Break 1615: Barnaby Brown Problems playing a modern reproduction of the silver pipes of Ur 1715 – 1800: Round table Friday 23 November Chair: Myriam Marcetteau 1000: Max Stern Shofar: Sound, Shape and Symbol. The shofar has always been considered a magical instrument associated with the revelation of God’s voice at Mount Sinai. Later, Joshua brought down the walls of Jericho with shofar blasts – in the ancient world, sound was known to influence matter. The shofar is the oldest surviving instrument still used in Jewish ritual. Its sound, shape, and symbolism are integral to the High Holiday Season. This lecture-demonstration exhibits a variety of shofar types and discusses their origins from animal to instrument through visual aids. It demonstrates the traditional shofar blast and deals with historical and symbolical issues aroused by it strident sonority. It concludes with a DVD presentation of the shofar as an artistic instrument, integrated into a contemporary biblical work by the author. 1100: Tea Break 1130 : Malcolm Miller: The music of the Shofar: ancient symbols, modern meanings. -

Public Policy Fellows Fall 2019

PUBLIC POLICY FELLOWS FALL 2019 Asher Allman Legislative Aide, U.S. Senate Committee on Veteran’s Affairs Mr. Allman is currently a Legislative Aide for the U.S. Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs. He handles the issues of adaptive sporting programs, Second Amendment rights, service dogs, monuments and memorials, and VA cemeteries. Prior to working for the Committee, he was the Legislative Correspondent responsible for the defense, veterans, homeland security, and commerce, technology, and telecommunications issue portfolios in the office of Sen. Roy Blunt of Missouri. A Kansas City native, he is a 2013 graduate of Missouri State University where he studied cultural and regional geography. He has a master’s in global studies, and graduate certificate in homeland security and defense, also from Missouri State University. Olivia Babine Legislative Aide, Office of Rep. Scott Tipton Ms. Babine currently serves as a Legislative Aide for Rep. Scott Tipton handling issues related to science, space, technology, postal reform, arts and humanities, census, and social welfare. She is a 2015 graduate of Saint Anselm College where she received a B.A. in International Relations and Economics. In 2018, she received her Graduate Certificate in Military Resilience from Liberty University. Currently, she attends the Naval War College where she is taking classes to attain her M.A. in Defense and Strategic Studies. Over the past few years, she has participated in several fellowships including the Hoover Institute’s Economic Fellowship and the Wilson Center’s Cyber Lab, AI Lab, and Foreign Policy Fellowship. Before working on Capitol Hill, she studied abroad in Morocco and Cuba and then taught English as a foreign language for one year in Seoul, South Korea. -

Rehabilitating Assad: the Arab League Embraces a Pariah by David Schenker

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 3481 Rehabilitating Assad: The Arab League Embraces a Pariah by David Schenker May 4, 2021 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS David Schenker David Schenker is the Taube Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute and former Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs. Brief Analysis Parochial interests and war fatigue are driving many member states to support premature elections and normalization with Damascus, but this approach will only consolidate Assad’s control and help him evade accountability for war crimes. n recent weeks, momentum has been building toward reintegrating Syria into the Arab League. The country was I suspended from the organization in November 2011, eight months into a brutal regime suppression effort that had killed 5,000 civilians. Ten years on and with an estimated 500,000 dead, several Arab states—encouraged by Russia—are taking steps to end the decade-long isolation of Bashar al-Assad and restore Syria’s membership. Although the Arab League is an archaic, dysfunctional, and largely irrelevant organization, the move is nevertheless significant for what it signals: a greater regional willingness to engage with Assad politically and economically. Consistent with UN Security Council Resolution 2254 (2015), U.S. policy has premised any such reengagement on a valid political transition, but regional states may undermine the prospects for real change by welcoming Damascus back into the fold prematurely. Increased Arab Engagement U pon suspending Syria for refusing to implement the Arab League peace plan in 2011, the organization levied a series of sanctions that included travel bans on some senior regime officials and limitations on investments and dealings with the Central Bank of Syria. -

Extensions of Remarks E1725 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

November 21, 2013 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1725 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS RECOGNIZING THE CENTENNIAL RECOGNIZING THE ROLLING FAM- SECOND CHANCE ACT CELEBRATION OF SAINT EPHRA- ILY AS THE 2013 HOLMES COUN- IM’S SYRIAC ORTHODOX CHURCH TY, FLORIDA, FARM FAMILY OF HON. BARBARA LEE IN CENTRAL FALLS, RHODE IS- THE YEAR OF CALIFORNIA LAND IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES HON. JEFF MILLER Thursday, November 21, 2013 HON. DAVID N. CICILLINE Ms. LEE of California. Mr. Speaker, I rise OF FLORIDA today in strong support of reauthorizing the OF RHODE ISLAND IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Second Chance Act. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES I’d like to thank my dear friend and col- Thursday, November 21, 2013 league Rep. Danny Davis for being such a Thursday, November 21, 2013 vocal and tireless advocate on what is a crit- Mr. MILLER of Florida. Mr. Speaker, it is ical issue for communities in my district and Mr. CICILLINE. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to with great pleasure that I rise to recognize the throughout the country. recognize the centennial celebration of Saint Rolling family for being selected as the 2013 I’d also like to thank my colleague Jim Sen- Ephraim’s Syriac Orthodox Church in Central Holmes County, Florida, Farm Family of the senbrenner for his work on this issue and for Falls, Rhode Island. Year. introducing, along with Congressman Davis, In the late 19th century, a small, close-knit Jeremy Rolling first discovered his love for H.R. 3465 which would reauthorize this impor- group of Syriac families living in Turkey and farming at the young age of four, while riding tant law. -

War Crimes Prosecution Watch, Vol. 14, Issue 06 -- April 27, 2019

PILPG Logo Case School of Law Logo War Crimes Prosecution Watch Editor-in-Chief Alexandra Hassan FREDERICK K. COX Volume 14 - Issue 06 INTERNATIONAL LAW CENTER April 27, 2019 Technical Editor-in-Chief Kurt Harris Founder/Advisor Michael P. Scharf Managing Editors Gloria Neilson Faculty Advisor Mary Preston Jim Johnson War Crimes Prosecution Watch is a bi-weekly e-newsletter that compiles official documents and articles from major news sources detailing and analyzing salient issues pertaining to the investigation and prosecution of war crimes throughout the world. To subscribe, please email [email protected] and type "subscribe" in the subject line. Opinions expressed in the articles herein represent the views of their authors and are not necessarily those of the War Crimes Prosecution Watch staff, the Case Western Reserve University School of Law or Public International Law & Policy Group. Contents AFRICA NORTH AFRICA Libya Thugs and Extremists Join Battle for Tripoli, Complicating Libyan Fray (The New York Times) Libya: Heavy shelling and civilian deaths ‘blatant violation’ of international law – UN envoy (UN News) Libyan government deplores inhuman acts of Haftar’s armed groups (The Libyan Observer) Gunmen attack migrant detention center in Libya’s Tripoli (The Washington Post) CENTRAL AFRICA Central African Republic Central African Republic: Six armed groups sign peace agreement in Bria (Relief Web) Without Justice in the Central African Republic, ‘Everything Else is Wrecked (Human Rights Watch) Central African Republic: Don’t -

Talking Foreign Policy: Responding to Rogue States

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2019 Talking Foreign Policy: Responding to Rogue States Paul Williams Todd F. Buchwald James Johnson Michael P. Scharf Milena Sterio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, and the International Law Commons CASE WESTERN RESERVE JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAw 51 (2019) TALKING FOREIGN POLICY: RESPONDING TO ROGUE STATES "Talking Foreign Policy" is a one-hour radio program, hosted by the Dean of Case Western Reserve University School of Law, Michael Scharf, in which experts discuss the important foreign policy issues. The premier broadcast (airdate: March 1, 2012) covered the controversial use of predator drones, humanitarian intervention in Syria, and responding to Iran's acquisition of nuclear weapons. Subsequent broadcasts have covered topics such as the challenges of bringing indicted tyrants to justice, America's Afghanistan exit strategy, the issue of presidential power in a war without end, and President Obama's second term foreign policy team. This broadcast focused on the responding to rogue states. The purpose of the radio show is to cover some of the most salient foreign policy topics and discuss them in a way that can make it easier for listeners to grasp. "Talking Foreign Policy" is recorded in the WCPN 90.3 Ideastream studio, Cleveland's NPR affiliate. Michael Scharf is joined each session with a few expert colleagues known for their ability to discuss complex topics in an easy-to-digest manner: * The ambassador: Todd F. -

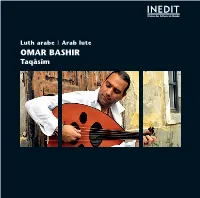

Omar Bashir. Taqasim

MCM W260144 Livret:livret 10/04/12 11:48 Page1 Luth arabe | Arab lute OMAR BASHIR Taqâsîm MCM W260144 Livret:livret 10/04/12 11:48 Page2 unir Bachir, le maître légendaire du ‘oud, a eu chercher sa propre identité musicale en expérimen- M plusieurs élèves mais un seul disciple, son fils tant différents instruments et techniques, et en Omar auquel il enseigna son art dès que l’enfant eut explorant des styles musicaux qui lui sont proches, atteint sa cinquième année. Il venait de rentrer en qu’ils soient ceux des tziganes hongrois ou des Irak avec sa femme hongroise et leurs deux enfants, gitans. Les Gypsy King l’autorisent même à utiliser Saad né en 1966 et Omar né en 1970, après avoir l’une de leurs chansons. Il collabore avec plusieurs obtenu en Hongrie son doctorat, passé quelques artistes internationaux, comme tout récemment années au Liban et amorcé une carrière internationale. Jordi Savall, reçoit distinctions et prix dans le monde Omar suit des cours quotidiens avec son père qui arabe, aux Etats-Unis et en Europe où il effectue plu- lui consacre parfois plus de cinq heures par jour. sieurs tournées de concerts et enregistre dix neuf CD. À sept ans il entre à l’école de musique et de danse Dans les enregistrements de ce CD il a voulu mettre de Bagdad dont il deviendra plus tard l’un des pro- en valeur, à partir d’improvisations sur quelques-uns fesseurs après avoir donné, à l’âge de neuf ans, un des maqams arabes les plus importants, leur relation premier concert de ‘oud en solo au Conservatoire avec d’autres cultures. -

Cahiers D'ethnomusicologie, 11

Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie Anciennement Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles 11 | 1998 Paroles de musiciens Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/673 ISSN : 2235-7688 Éditeur ADEM - Ateliers d’ethnomusicologie Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 janvier 1998 ISBN : 2-8257-0639-6 ISSN : 1662-372X Référence électronique Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie, 11 | 1998, « Paroles de musiciens » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 14 décembre 2011, consulté le 06 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/673 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 6 mai 2019. Tous droits réservés 1 Comment les musiciens témoignent-ils verbalement de leur pratique vocale ou instrumentale ? Que disent-ils de la musique qu'ils jouent ? Quelle valeur et quelle signification donnent-ils à leur pratique ? Dans quel cadre s'inscrit-elle pour eux ? Et encore, quels discours font ceux qui, dans une culture donnée, réfléchissent au pourquoi et au comment de la création artistique : théoriciens, philosophes, esthètes, poètes ?... Quelles sont les dimensions cognitives et extramusicales de la musique ? En un mot, comment les musiciens pensent-ils la musique ? Tel est le thème de ce dossier, qui nous offre un état de la question à travers une série d'études de cas représentatifs de régions aussi différentes que le désert de Namibie, le Tchad, le Maroc, le Pays basque, la Bretagne, la Sardaigne, la Silésie, l'Afghanistan, le Tibet, la Chine et l'Australie. Fondés à Genève en 1988 dans le cadre des Ateliers d'ethnomusicologie, les Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles proposent à leurs lecteurs une publication annuelle. Chaque ouvrage est centré sur un dossier thématique, complété par des rubriques d'intérêt général : entretiens, portraits et comptes rendus. -

Criminal Responsibility of Heads of State for Human

CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY OF HEADS OF STATE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS: WILL THE KING EVER SUBMIT HIMSELF TO THE LAW? By Walter Acii Ojok Submitted to Central European University Department of Legal Studies In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Law in Human Rights Supervisor: Professor Ana Filipa Vrdoljak CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Ana Vrdoljak for supervising and guiding me in this thesis. I also particularly thank her for encouraging me to explore, to a further depth, a realm of public international law that I would not have appreciated as much if I had not done this work. Many more thanks go to my family, especially to my siblings back in Uganda, who I hope will be inspired by my life journey. CEU eTD Collection i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................. iv CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 1 1.1 Summary Layout of Thesis .............................................................................................5 CHAPTER 2: A CRIMINAL REPRESSION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS: TOWARDS ENFORCEMENT................................................ 6 2.1 Redress of Human Rights Violations in the Post 1945 Era ...........................................6 2.2 The Emerging International Criminal Law: