NPS Archeology Program: Research in the Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Western Railway Ships - Wikipedi… Great Western Railway Ships from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

5/20/2011 Great Western Railway ships - Wikipedi… Great Western Railway ships From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Great Western Railway’s ships operated in Great Western Railway connection with the company's trains to provide services to (shipping services) Ireland, the Channel Islands and France.[1] Powers were granted by Act of Parliament for the Great Western Railway (GWR) to operate ships in 1871. The following year the company took over the ships operated by Ford and Jackson on the route between Wales and Ireland. Services were operated between Weymouth, the Channel Islands and France on the former Weymouth and Channel Islands Steam Packet Company routes. Smaller GWR vessels were also used as tenders at Plymouth and on ferry routes on the River Severn and River Dart. The railway also operated tugs and other craft at their docks in Wales and South West England. The Great Western Railway’s principal routes and docks Contents Predecessor Ford and Jackson Successor British Railways 1 History 2 Sea-going ships Founded 1871 2.1 A to G Defunct 1948 2.2 H to O Headquarters Milford/Fishguard, Wales 2.3 P to R 2.4 S Parent Great Western Railway 2.5 T to Z 3 River ferries 4 Tugs and work boats 4.1 A to M 4.2 N to Z 5 Colours 6 References History Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the GWR’s chief engineer, envisaged the railway linking London with the United States of America. He was responsible for designing three large ships, the SS Great Western (1837), SS Great Britain (1843; now preserved at Bristol), and SS Great Eastern (1858). -

Pioneer Steamships in Queensland Waters

PIONEER STEAMSHIPS IN QUEENSLAND WATERS. (By A. G. Davies). (Read at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, March 31, 1936). My purpose in this paper is to give you a concise history of the building up of Queensland's maritime trade—or at all events the part which the steamship played in it. I, however, want first to refer in pass ing to two vessels using steam power which had noth ing to do with mercantile activities. These were the "Sophia Jane" and the "James Watt," both of which were mentioned in my paper on "The Genesis of the Port of Brisbane." After having been engaged in the coastal trade, mostly in New South Wales, for a few years the "Sophia Jane" was broken up in 1845. In the following year a wooden paddle steamer named the "Phoenix" was built in Sydney and the engines which had been taken out of the "Sophia Jane" were put into her. This vessel was engaged in the service between Sydney and the Clarence River for five years, and was then wrecked at the entrance to that river. All that is left, therefore, of the engines of the first steamship to come to Aus- ralia lies in the shifting sands in that locality. When the s.s. "James Watt" was broken up in 1847, her engines were put into another vessel, the "Eagle," which had been built at Pyrmont, Sydney. The "Eagle's" first visit to Moreton Bay was made on August 8, 1849. She was then in charge of Cap tain Allen, who previously had been coming to More- ton Bay in the steamship "Tamar. -

The Mythologizing of the Great Lakes Whaleback

VERNACULAR IN CURVES: THE MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE GREAT LAKES WHALEBACK by Joseph Thaddeus Lengieza April, 2016 Director of Thesis: Dr. Bradley Rodgers Major Department: Maritime Studies, History The “whaleback” type of bulk commodity freighter, indigenous to the Great Lakes of North America at the end of the nineteenth century, has engendered much notice for its novel appearance; however, this appearance masks the essential vernacularity of the vessel. Comparative disposition analysis reveals that whalebacks experienced longevity comparable to contemporary Great Lakes freighter of similar construction material and size, implying that popular narrative overstates whaleback abnormality. Market and social forces which contributed to the rise and fall of the whaleback type are explored. VERNACULAR IN CURVES: THE MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE GREAT LAKES WHALEBACK A Thesis Presented To the Faculty of the Department of Maritime Studies East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Maritime Studies by Joseph Thaddeus Lengieza April, 2016 © Joseph Thaddeus Lengieza, 2016 VERNACULAR IN CURVES: THE MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE GREAT LAKES WHALEBACK By Joseph Thaddeus Lengieza APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS:_________________________________________________________ Bradley Rodgers, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: _______________________________________________________ Nathan Richards, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: _______________________________________________________ David Stewart, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: _______________________________________________________ -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service WAV 141990' National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Cobscook Area Coastal Prehistoric Sites_________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts ' • The Ceramic Period; . -: .'.'. •'• •'- ;'.-/>.?'y^-^:^::^ .='________________________ Suscruehanna Tradition _________________________ C. Geographical Data See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in j£6 CFR Part 8Q^rjd th$-§ecretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. ^"-*^^^ ~^~ I Signature"W"e5rtifying official Maine Historic Preservation O ssion State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County -

MS-042 John T. Reeder Photograph Collection

John T. Reeder Photograph Collection MS-042 Finding aid prepared by Elizabeth Russell, revised by Rachael Bussert. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit June 26, 2014 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections 1400 Townsend Drive Houghton, Michigan, 49931 906-487-2505 [email protected] John T. Reeder Photograph Collection MS-042 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 4 Biography.......................................................................................................................................................5 Collection Scope and Content Summary...................................................................................................... 5 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 Series I, Inventories and General Records..............................................................................................8 -

Where Steam Engines Meet Sandstone

TIMETABLE 2 01 9 Where steam engines meet sandstone. 1 Experience boat travel Established 1836! Dear Guests, Steamboat 90 years Leipzig With its nine historical paddle steamers, the Sächsische Dampfschif- Put into service: 11.05.1929 fahrt is the oldest and largest steamboat fleet in the world. In excep- tional manner and depth, this service combines riverside experience, Steamboat Dresden technical fascination and culinary delight. While you are amazed by Put into service: 02.07.1926 the incomparable Elbe landscape with the imposing rock formations in Saxon Switzerland, the impressive buildings of Dresden and Meissen, Steamboat Pillnitz and the delightful wine region between Radebeul and Diesbar-Seusslitz Put into service: 16.05.1886 you can also enjoy regional and seasonal food and beverages. Whether travelling with the lovingly restored paddle steamers or with the air- Steamboat Meissen conditioned salon ships, lean back and enjoy the breathtaking views. Put into service: 17.05.1885 We would like to impress you with our comprehensive offer of expe- riences and hope to continually surprise you. With this I would like to Steamboat 140 wish you an all-encompassing, relaxing trip on board. years Stadt Wehlen Put into service: 18.05.1879 Yours, Karin Hildebrand Steamboat Pirna Put into service: 22.05.1898 Steamboat Kurort Rathen contents Put into service: 02.05.1896 En route in Dresden city area 4 Steamboat Our special event trips 8 Krippen Put into service: 05.06.1892 Winter and Christmas Cruises 22 En route in and around Meissen 26 Steamboat En route in Saxon Switzerland 28 Diesbar Put into service: 15.05.1884 Our KombiTickets 32 Dresden’s “Terrassenufer” under steam 40 Motor ship 25 Anniversary ships 42 years August der Starke put into service: 19.05.1994 Historic Calendar 44 Souvenirs & Co. -

Hands Lost Kamloops • Isle Royale • Lake Superior

All Hands Lost Kamloops • Isle Royale • Lake Superior Text by Curt Bowen Photography by Mel Clark and Curt Bowen Captain William Brian, wet and frozen from the brutal storm, gripped the wooden wheel, his knuckles sharp and white against the battered red of his hands. Near gale force winds smashed wave after wave across the decks of his ship, the Kamloops. The 250-foot, 2,226-ton, iron cargo ship was in a battle for her life, and all aboard knew that only his skill, and the grace of God, stood between them and the ravenous waters of Lake Superior. Rounding the northern tip of Isle Royale, the vessel had a straight shot towards the protective port of Thunder Bay, only a few hours ahead. First Mate Henry Genest’s eyes strained towards the bow of the ship, always on the watch for rocks or other vessels to appear through the driving sleet and snow. With the wind and waves approaching from the starboard stern, Captain Brian reached over and shifted the ship’s telegraph into the full ahead position. Chief Engineer Jac Hawman, bracing himself against the engine’s boiler, acknowledged the change in engine power. Loud and urgent, he shouted for more coal to be shoveled into the burners. Covered in black coal dust and sweat, the two ship’s firemen, Andy Brown and Harry Wilson, worked with a will to stoke the engines, fighting to keep upright as the ship lurched from port to starboard. Above the engine room, the remaining 17 crewmembers could do nothing but pray, braced against their bunks and trying not to be thrown onto the deck. -

04 Dive Trail History.Cdr

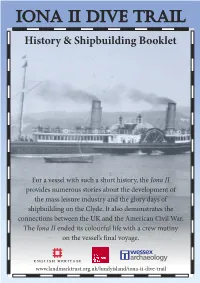

Iona II Dive trail History & Shipbuilding Booklet For a vessel with such a short history, the Iona II provides numerous stories about the development of the mass leisure industry and the glory days of shipbuilding on the Clyde. It also demonstrates the connections between the UK and the American Civil War. The Iona II ended its colourful life with a crew mutiny on the vessel’s final voyage. www.landmarktrust.org.uk/lundyisland/iona-ii-dive-trail navigating the wreck Parts of this Information Booklet correspond with the Shipbuilding Underwater Guide. The letters on the plan below are also on the Shipbuilding Underwater Guide and correspond to areas of interest around the wreck which are explored further in this booklet. The Iona II wreck site is on the east coast of Lundy Island. The seabed around the Iona II wreck is generally flat, with a slight slope east of the amidships area. The seabed is coarse, firm, level mud and fine silt with some areas of fine sand within the wreck and some gravel patches around the boilers. The wreck lies at 22 to 28 metres depending upon the state of the tide. Visibility can vary from 1 to 15 metres. The best time to dive is at slack water, which is two hours either side of low water. N F G A B E Ro D ber t C 0 10m Access to the Iona II Dive Trail is via the Robert wreck buoy. From the Robert’s rudder, head 35m on a bearing of 245 degrees or WSW to reach the Iona II. -

Shipwreck Surveys of the 2018 Field Season

Storms and Strandings, Collisions and Cold: Shipwreck Surveys of the 2018 Field Season Included: Thomas Friant, Selah Chamberlain, Montgomery, Grace Patterson, Advance, I.A. Johnson State Archaeology and Maritime Preservation Technical Report Series #19-001 Tamara L. Thomsen, Caitlin N. Zant and Victoria L. Kiefer Assisted by grant funding from the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute and Wisconsin Coastal Management Program, and a charitable donation from Elizabeth Uihlein of the Uline Corporation, this report was prepared by the Wisconsin Historical Society’s Maritime Preservation and Archaeology Program. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute, the National Sea Grant College Program, the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program, or the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association. Note: At the time of publication, Thomas Friant and Montgomery sites are pending listing on the State and National Registers of Historic Places. Nomination packets for these shipwreck sites have been prepared and submitted to the Wisconsin State Historic Preservation Office. I.A. Johnson and Advance sites are listed on the State Register of Historic Places pending listing on the National Register of Historic Places, and Selah Chamberlain site is listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places. Grace Patterson site has been determined not eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Cover photo: A diver surveying the scow schooner I.A. Johnson, Sheboygan County, Wisconsin. Copyright © 2019 by Wisconsin Historical Society All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS AND IMAGES ............................................................................................. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................ -

Oscillating Steam Engine by John Penn & Sons in the Steamboat Diesbar

OSCILLATING STEAM ENGINE BY JOHN PENN & SONS IN THE STEAMBOAT DIESBAR Photo: Olivier Bachmann Designated a Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark July 2nd, 2008 Dresden, Germany A history of the Fleet Paddle steamers have been plying the waters of the River Elbe in Saxony since 1836. In March of that year local merchants in Dresden first pursued the idea of using the river for the transportation of both material goods and passenger traffic. In July of 1836 a royal Saxon decree permitted the merchants the privilege of steam navigation on the river, and the “Elbdampfschiffahrts‐Gesellschaft” was founded shortly afterward. The maiden voyage of the passenger steamer Königin Maria took place the following year. In 1867 the company changed its name to “Sächsisch‐Böhmische Dampfschiffahrts‐Gesellschaft”, to reflect its expanded regional reach, which included neighboring Bohemia as well as Saxony. In the prime of its development and at the zenith of its growth around 1900, the company featured a fleet of 37 steamers and carried up to 3.6 million passengers annually. These numbers have never been matched! The official poster from 1936 to commemorate 100 years of steamboating on the Elbe. Image: Sächsische Dampfschiffahrt Two World Wars and significant geographical and political changes in Europe took their toll on the nature and structure of steam navigation on the Elbe. After World War II, the majority of the fleet of steamers was either destroyed or confiscated to contribute to wartime reparations. Following the establishment of the Soviet‐controlled German Democratic Republic (GDR), the company was nationalized and in 1948 took the name of “Elbschiffahrt Sachsen”. -

The Sail & the Paddle Part Ii

THE SAIL & THE PADDLE PART II The tug-of-war between the screw-driven Rattler (left) and Alecto (right) was more of an exhibition to convince public opinion than a scientific test, as the Royal Navy had already ordered seven screw driven ships by March 1845. o far as the merchant ship was concerned, the propeller was almost universally recognised as the most efficient mans of ship propulsion, but the warship in general remained wedded Sto sail. This was to some extent understandable, particularly in Britain, which had emerged from the last great war as undisputed master of all the oceans. She still maintained the largest fighting fleet in the world, and the officers and men who had manned that navy in war were still serving in it. A radical change from wood and sail to iron and steam meant starting the navy again from scratch, with the present superiority of numbers wiped out at a stroke. But with the invention of the propeller the overriding objection to steam propulsion in warships, the vulnerable paddlewheel, had been removed , and the steam engine at last had to be admitted into naval ships. But it was not admitted without a struggle by traditionalists, and there was still much argument in naval circles in all countries as to weather the propeller was really superior to the paddlewheel. The argument was finally settled in 1845, when two virtually identical frigates of 880 tons, H.M.S. Rattler and H.M.S. Alecto, were both fitted with engines of 220 horsepower, that in H.M.S.