Full Book PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Formation of the Communist Party of Germany and the Collapse of the German Democratic Republi C

Enclosure #2 THE NATIONAL COUNCI L FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEA N RESEARC H 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D.C . 20036 THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : Politics Unhinged : The Formation of the Communist Party of Germany and the Collapse of the German Democratic Republi c AUTHOR : Eric D . Weitz Associate Professo r Department of History St . Olaf Colleg e 1520 St . Olaf Avenu e Northfield, Minnesota 5505 7 CONTRACTOR : St . Olaf College PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Eric D . Weit z COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 806-3 1 DATE : April 12, 199 3 The work leading to this report was supported by funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East Europea n Research. The analysis and interpretations contained in the report are those of the author. i Abbreviations and Glossary AIZ Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (KPD illustrated weekly newspaper ) Alter Verband Mineworkers Union Antifas Antifascist Committee s BL Bezirksleitung (district leadership of KPD ) BLW Betriebsarchiv der Leuna-Werke BzG Beiträge zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung Comintern Communist International CPSU Communist Party of the Soviet Unio n DMV Deutscher Metallarbeiter Verband (German Metalworkers Union ) ECCI Executive Committee of the Communist Internationa l GDR German Democratic Republic GW Rosa Luxemburg, Gesammelte Werke HIA, NSDAP Hoover Institution Archives, NSDAP Hauptarchi v HStAD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf IGA, ZPA Institut für Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, Zentrales Parteiarchi v (KPD/SED Central Party Archive -

Ottobre 2012 Anno 20 L’Isola Di San Giorgio Sede Della Fondazione Giorgio Cini

Anno 2012-20132012-2013 - numeronumero 3 / ottobre 20122012 Mensile RotaryRotarryy InternationInternationalal Distretto 20602060 AnnoAnnoXIA XI Aut.Auut. Trib. didi Treviso Treeviso n.n. 11771177 deldel 18/02/200318/02/2003 ottobre 20122012 Abb.Abb. AnnuoAnAnnuo € 4,004,00 PostePoste ItalianeItaliane SpedizioneSSppeddiizziione inin abbonamentoaabbbonamenntto postalepostaalle - 70% - NNE/TNE/TN TassaTassa PPagataagaatta / TaTaxeaxxe PPerçueerçue / PrioritariPrioritarioo NOTIZIARIO DELGOVERNATOREALESSANDROPEROLO NOT Friuli VeneziaGiulia –Trentino - AltoAdige /Südtirol –Veneto Friuli VeneziFriuli Venezi I Z IARI O D O D L’isola diSanGiorgiosede della FondazioneGiorgioCini a Trentino -AltoA o tirol –Venet G E iuli L GO a D DISTRETTO 2060 – I VER Trentino -Alto A ST RE NNA AAT TTO TTO TO RE 206 ALESSANDRO PEROLO d 0 i g e / Sü d tirol –Venet Conosci l’Olio vinacciolo di Semi d’Uva? “Seme d’Uva” E’ un olio sano, di altissimo valore dietetico. Anzi, sotto questo profilo, è l’olio più indicato perchè è il più ricco di ACIDI GRASSI POLINSATURI ed in particolare di a.g. LINOLEICO. Questo è un vero dono della natura per contribuire a ridurre nei limiti della norma l’eccesso di colesterolo e di trigliceridi, tradizionali nemici della nostra salute. Bastano poche cifre per far apparire evidente la differenza con gli altri oli olio di oliva a.g. linoleico 8% ca. olio di arachidi a.g. linoleico 29% ca. olio di soia a.g. linoleico 51% ca. olio di mais a.g. linoleico 56% ca. OLIO DI SEMI D’UVA a.g. linoleico 72% ca. In “Mangiare meglio per vivere meglio”, opera redatta con la super visione dell’ISTITUTO NAZIONALE DELLA NUTRIZIONE, si legge: “...Tutti gli animali hanno bisogno di acidi grassi polinsaturi come è appunto l’acido linoleico - e l’uomo ne ha una necessità primaria”. -

As Meditações De Dédalo.Pdf

Prova Final para término do curso de Arquitectura, orientada pelo Arquitecto Jorge Figueira. Departamento de Arquitectura da Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra. Fevereiro 2005 / © João David Esteves Baptista ([email protected]) ao Tó, à Gabriela e ao Chico ÍNDICE Introdução 7 I.Parte: A ideia do Labirinto 1. (in)definições 11 2. Evolução histórica 18 II.Parte: Casos de Estudo 3. Electric Labyrinth 47 4. Musée Mondial 56 5. New Babylon 73 6. Brick Country House 93 III.Parte: As meditações de Dédalo 7. O Espaço Labiríntico 123 8. Vers une labyrintecture 135 Notas 147 Referências bibliográficas e fílmicas 197 Fontes das ilustrações 207 Agradecimentos 211 INTRODUÇÃO Este trabalho tem como objectivo o estudo da relação entre o labirinto (enquanto símbolo e conceito) e a arquitectura. Procurar-se-á não só analisar a evolução histó- rica deste arquétipo, mas também apresentar uma série de casos específicos, culmi- nando numa reflexão crítica sobre a metáfora espacial labiríntica enquadrada no pa- norama da arquitectura e sociedade contemporâneas. A prova estará dividida em 3 partes distintas: Uma primeira, de carácter mais histórico, é apresentada de forma sumária, procu- rando-se antes de mais entender quais as origens desta figura e o seu desenvolvi- mento através dos tempos. Tendo surgido há mais de 4000 anos, este potente sím- bolo sofreu constantes mutações: desde o lendário labirinto de Creta até ao recente parque temático, serão estas as duas “pontas do fio” aqui desenrolado na forma de um percurso optimizado através das diferentes manifestações labirínticas. A segunda parte do trabalho será apresentada sob a forma de case studies, onde o que se pretende é claramente estabelecer uma maior aproximação entre o conceito de labirinto e a prática da arquitectura. -

Separation After Unification? the Crisis of National Identity in Eastern Germany

Separation After Unification? The Crisis of National Identity in Eastern Germany Andreas Staab Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy London School of Economics and Political Science University of London December 1996 i UMI Number: U615798 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615798 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I S F 7379 OF POLITICAL AND S&uutZ Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks to George Schopflin for having taken the time and patience to supervise my work. His professional advice have been of immense assistance. I have also greatly benefited from the support and knowledge of Brendan O’Leary, Jens Bastian, Nelson Gonzalez, Abigail Innes, Adam Steinhouse and Richard Heffeman. I am also grateful to Dieter Roth for granting me access to the data of the ‘Forschungsgruppe Wahlen ’. Heidi Dorn at the ‘Zentralarchiv fur Empirische Sozialforschung ’in Cologne deserves special thanks for her ready co-operation and cracking sense of humour. I have also been very fortunate to have received advice from Colm O’Muircheartaigh from the LSE’s Methodology Institute. -

The Symbolic Representation of Socialist Landscapes in the Visual Arts of the German Democratic Republic

Rethinking Marxism A Journal of Economics, Culture & Society ISSN: 0893-5696 (Print) 1475-8059 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrmx20 Subversive Landscapes: The Symbolic Representation of Socialist Landscapes in the Visual Arts of the German Democratic Republic Oliver Sukrow To cite this article: Oliver Sukrow (2017) Subversive Landscapes: The Symbolic Representation of Socialist Landscapes in the Visual Arts of the German Democratic Republic, Rethinking Marxism, 29:1, 96-141, DOI: 10.1080/08935696.2017.1316108 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08935696.2017.1316108 Published online: 26 Jun 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 148 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rrmx20 Download by: [46.5.19.17] Date: 05 August 2017, At: 03:07 RETHINKING MARXISM, 2017 Vol. 29, No. 1, 96–141, https://doi.org/10.1080/08935696.2017.1316108 Subversive Landscapes: The Symbolic Representation of Socialist Landscapes in the Visual Arts of the German Democratic Republic Oliver Sukrow This essay on the visual representation of landscapes in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) suggests the historical and aesthetic significance of romantic traditions of the nineteenth century for the Socialist cultural practice of the GDR as well as for theoretical reflections on the importance of landscape and nature for the development of a Socialist society. With such a comparative approach, we can not only interpret philosophical work by Lothar Kühne as a Marxist reflection on romantic notions of the importance of landscape but we can also trace the stylistic influence of romantic artists like Caspar David Friedrich on the GDR’s Socialist landscape painting. -

In Appreciation of Ludwig Erhard

Volume 9. Two Germanies, 1961-1989 No New Wallpaper (April 10, 1987) In this widely read interview, Kurt Hager, the member of the Politburo in charge of ideological issues, defends the party‟s policies and sets them apart from reform efforts in the Soviet Union. The interview was first published in Stern, a West German magazine, and reprinted one day later in full length in Neues Deutschland, the news organ of the SED. Kurt Hager answers questions for Stern magazine Question: The SED leadership supports the reforms introduced by Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union. At the same time, the GDR emphasizes its own independence. Are the times in which the land of Lenin set an example for German communists long gone? Answer: The GDR and the Soviet Union are allies. They have concluded a treaty on friendship, cooperation, and mutual support. There is a firm, indestructible friendship between the people of these two countries, and this finds expression in the direct relations between companies, universities, and other institutions, as well as countless personal meetings. The SED and the CPSU [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] are sister parties, and they regularly share their experiences with each another, in order to learn from each other. That is how it has been, how it is, and how it will continue to be in the future. Question: So the slogan “Learning from the Soviet Union means learning to win” no longer applies? Answer: I remember that Mikhail Gorbachev, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU, said on the occasion of the 11th party congress of the SED in April 1986: “You know that our party and our people have always stood by you in all these years since the war, always prepared to help the young state of workers. -

Challenging Censorship Through Creativity: Responses to the Ban on Sputnik in the GDR', Modern Language Review, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer Challenging censorship through creativity Citation for published version: Bradley, L 2013, 'Challenging censorship through creativity: responses to the ban on Sputnik in the GDR', Modern Language Review, vol. 108, no. 2, pp. 519-538. https://doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.108.2.0519 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.5699/modelangrevi.108.2.0519 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Modern Language Review Publisher Rights Statement: © Bradley, L. (2013). Challenging Censorship through Creativity: Responses to the Ban on Sputnik in the GDR. Modern Language Review, 108(2), 519-538doi: 10.5699/modelangrevi.108.2.0519 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Challenging Censorship through Creativity: Responses to the Ban on Sputnik in the GDR Author(s): Laura Bradley Source: The Modern Language Review, Vol. 108, No. 2 (April 2013), pp. 519-538 Published by: Modern Humanities Research Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5699/modelangrevi.108.2.0519 . -

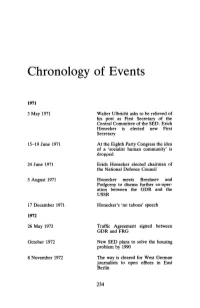

Chronology of Events

Chronology of Events 1971 3 May 1971 Walter Ulbrlcht asks to be relieved of bis post as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the SED. Erlch Honecker is elected new First Secretary 15-19 June 1971 At the Eighth Party Congress the idea of a 'socialist human community' is dropped 24 June 1971 Erlch Honecker elected chairman of the National Defence Council 5 August 1971 Honecker meets Brezhnev and Podgomy to discuss further co-oper ation between the GDR and the USSR 17 December 1971 Honecker's 'no taboos' speech 1972 26 May 1972 Trafik Agreement signed between GDRandFRG October 1972 New SED plans to solve the housing problem by 1990 8 November 1972 The way is cleared for West German journalists to open offices in East Berlin 234 Chronology 0/ Events 235 21 December 1972 Basic Treaty signed as a first step towards 'normalising' relations between GDR and FRG 1973 21 February 1973 A new regulation against foreign journalists slandering the GDR, its institutions and leading figures 1 August 1973 Walter Ulbricht dies at the age of 80 18 September 1973 East and West Germany are accepted as members of the United Nations 2 October 1973 The Central Committee approves a plan to step up the housing programme 1974 1 February 1974 East German citizens are permitted to possess Western currency 20 June 1974 Günter Gaus becomes the first 'Permanent Representative' of the FRG in the GDR 7 October 1974 Law on the revision of the constitution comes into effect. Concept of one German nation is dropped and doser ties with the Soviet Union stressed 1975 1 August 1975 Helsinki Final Act signed 7 October 1975 Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Aid between GDR and Soviet Union 16 December 1975 Spiegel reporter Jörg Mettke expelled after another Spiegel reporter publishes a story on compulsory adop tion in the GDR 1976 29-30 June 1976 Conference of 29 Communist and 236 Chronology 0/ Events Workers' Parties in East Berlin. -

Anti-Nazi Exiles German Socialists in Britain and Their Shifting Alliances 1933-1945

Anti-Nazi Exiles German Socialists in Britain and their Shifting Alliances 1933-1945 by Merilyn Moos Anti-Nazi Exiles German Socialists in Britain and their Shifting Alliances 1933-1945 by Merilyn Moos Community Languages Published by Community Languages, 2021 Anti-Nazi Exiles, by Merilyn Moos, published by the Community Languages is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Front and rear cover images copyright HA Rothholz Archive, University of Brighton Design Archives All other images are in the public domain Front and rear cover illustrations: Details from "Allies inside Germany" by H A Rothholz Born in Dresden, Germany, Rothholz emigrated to London with his family in 1933, to escape the Nazi regime. He retained a connection with his country of birth through his involvement with émigré organisations such as the Free German League of Culture (FGLC) in London, for whom he designed a series of fundraising stamps for their exhibition "Allies Inside Germany" in 1942. Community Languages 53 Fladgate Road London E11 1LX Acknowledgements We would like to thank Ian Birchall, Charmian Brinson, Dieter Nelles, Graeme Atkinson, Irena Fick, Leonie Jordan, Mike Jones, University of Brighton Design Archives. This work would not have been publicly available if it had not been for the hard work and friendship of Steve Cushion to whom I shall be forever grateful. To those of us who came after and carry on the struggle Table of Contents Left-wing German refugees who came to the UK before and during the Second -

'The Prague Exit': Representations of East German Migration in the Official Press of the Czechoslovak Communist Party"

Michalovska, Beatrice (2018) 'The Prague Exit': representations of East German migration in the official press of the Czechoslovak Communist Party". MPhil(R) thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/30736/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] School of Modern Languages and Cultures, College of Arts 'The Prague Exit': representations of East German migration in the official press of the Czechoslovak Communist Party © Author: Beatrice Michalovska Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the MPhil degree in Czech Supervised by Dr Mirna Šolić and Dr Jan Čulík October 2017 Table of contents Abstract .......................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................ 4 Abbreviations ................................................................................................... 5 Table of figures -

Download Download

The International Newsletter of Communist Studies XXIV/XXV (2018/19), nos. 31-32 111 Dietrich Orlow University of Boston United States The Last Hurrah: Hanna Wolf’s and Wolfgang Schneider’s May, 1989 Defense of Stalinism Abstract In May, 1989 the political power monopoly of the Communist parties in Eastern Europe was eroding. Political reforms in Poland and Hungary had essentially ended the rule of the Communist parties there. In the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost had fundamentally changed the face of Communist rule, in Czechoslovakia, Romania, and East Germany did the hardliners hold on. True, in the German Democratic Republic there were also calls for reforms from both inside and outside the ruling Communist party, the Socialist Unity Party (SED), but the party’s Politburo, led by Erich Honecker and Günter Mittag, resisted all calls for reforms and innovation. They were supported in this stance by an article entitled “On the History of the Comintern (Zur Geschichte der Komintern)” which appeared in the May 6/7 of Neus Deutschland, the SED’s official newspaper, The authors of this contribution, Hanna Wolf and Wolfgang Schneider, were well-known figures among the SED’s intellectual establishment. Wolf had been rector of the Parteihochschule “Karl Marx” from 1950 to 1983, and in 1989 she was a personal advisor to Erich Honecker. Schneider was a long-time faculty member at the Parteihochschule. The authors’ article was a response to a number of Soviet publications, which, using the new freedoms under glasnost were critically analyzing Stalin’s dictatorship. In their rebuttal Wolf and Schneider insisted, on the contrary, Stalin had never been a dictator; he was always subject to the democratic control of the CPSU’s Central Committee. -

ALIENATING LABOR: a DISSERTATION Anikó Eszter Bartha HISTORY 2007 in CEU Etd Collection Permission of the Author

ALIENATING LABOR: WORKERS ON THE ROAD FROM SOCIALISM TO CAPITALISM IN EAST GERMANY AND HUNGARY (1968-1989) Anikó Eszter Bartha A DISSERTATION IN HISTORY Presented to the Faculties of the Central European University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2007 CEU eTD Collection Supervisor of Dissertation and Ph. D. Director _______________________ Professor Jacek Kochanowicz Copyright Notice Copyright in the text of this dissertation rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Library of the Central European University. Details may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection 2 Abstract The rapid collapse of the Eastern European socialist regimes rendered the year of 1989 a watershed event. Because of the focus on political upheaval, 1989 was often seen as a “year zero” – an unquestionable turning point. This boundary was first challenged by economic history, which showed that the economic decline of the system started well before its political collapse. This dissertation seeks to explore the social roots of the decline of the socialist regimes through two factory case studies in East Germany and Hungary (Carl Zeiss Jena and Rába MVG in GyĘr) from the late 1960s until 1989. By undertaking a comparative study of the party’s policy towards the working class in these two, partly similar, partly different socialist environments, the dissertation locates common factors in order to answer the question of why there was no independent working-class action against the regimes during the examined period – in complete contrast to the Polish case – but neither did the workers defend the socialist system in 1989.