Grizzly Embracing the Berry Picker: Haida Artistic Expression in Argillite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

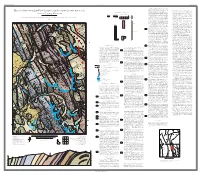

Source and Bedrock Distribution of Gold and Platinum-Group Metals in the Slate Creek Area, Northern.Chistochina Mining District, East-Central Alaska

Source and Bedrock Distribution of Gold and Platinum-Group Metals in the Slate Creek Area, Northern.Chistochina Mining District, East-Central Alaska By: Jeffrey Y. Foley and Cathy A. Summers Open-file report 14-90******************************************1990 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Manuel Lujan, Jr., Secretary BUREAU OF MINES T S Arv. Director TN 23 .U44 90-14 c.3 UNITED STATES BUREAU OF MINES -~ ~ . 4,~~~~1 JAMES BOYD MEMORIAL LIBRARY CONTENTS Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Acknowledgments 2 Location, access, and land status 2 History and production 4 Previous work 8 Geology 8 Regional and structural geologic setting 8 Rock units 8 Dacite stocks, dikes, and sills 8 Limestone 9 Argillite and sandstone 9 Differentiated igneous rocks north of the Slate Creek Fault Zone 10 Granitic rocks 16 Tertiary conglomerate 16 Geochemistry and metallurgy 18 Mineralogy 36 Discussion 44 Recommendations 45 References 47 ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Map of Slate Creek and surrounding area, in the northern Chistochina Mining District 3 2. Geologic map of the Slate Creek area, showing sample localities and cross section (in pocket) 3. North-dipping slaty argillite with lighter-colored sandstone intervals in lower Miller Gulch 10 4. North-dipping differentiated mafic and ultramafic sill capping ridge and overlying slaty argillite at upper Slate Creek 11 5. Dike swarm cutting Jurassic-Cretaceous turbidites in Miller Gulch 12 6 60-ft-wide diorite porphyry and syenodiorite porphyry dike at Miller Gulch 13 7. Map showing the locations of PGM-bearing mafic and ultramafic rocks and major faults in the east-central Alaska Range 14 8. Major oxides versus Thornton-Tuttle differentiation index 17 9. -

Geology of the Nimrod Area Granite County Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1958 Geology of the Nimrod area Granite County Montana Joel Kenneth Montgomery The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Montgomery, Joel Kenneth, "Geology of the Nimrod area Granite County Montana" (1958). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 7095. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/7095 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. aUv DATE DUE .**'“ '■’ K ^-r>o<> . t_A \J ^ D e c 0 1 ]ggg ^ A H 1 5 GEOLOGY OP THE NIMROD AREA GRANITE COUNTY, MONTANA by JOEL K. MONTGOMERY B. S. Brigham Young University, 1956 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1958 Approved by: Chairman, Board of ^aminers Dean, Graduate School 2 0 1953 bate UMl Number: EP37896 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT OisMftartion Publishing UMl EP37896 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Mineralogy and Geochemistry of Some Belt Rocks, Montana and Idaho

Mineralogy and Geochemistry of Some Belt Rocks, Montana and Idaho By J. E. HARRISON and D. J. GRIMES CONTRIBUTIONS TO ECONOMIC GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1312-O A comparison of rocks from two widely separated areas in Belt terrane UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1970 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 75-607766 4- V For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Price 35 cents CONTENTS Page Abstract .................................................................................................................. Ol Introduction ............................:.................................... .......................................... 2 General geology ...............................................................;.'................................... 3 Methods of investigation ........................y .............................................................. 7 Sampling procedure ..............................:....................................................... 7 Analytical technique for mineralogy ...............:............................................ 11 Analytical technique and calculations for geochemistry................................ 13 Mineralogy of rock types........................................................................................ 29 Geochemistry ......................................................................................................... -

Limestone Resources of Western Washington

State of Washington DANIEL J. EVANS, Governor Department of Conservation H. MA URI CE AHLQUIST, Director DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 52 LIMESTONE RESOURCES OF WESTERN WASHINGTON By WILBERT R. DANNER With a section on the UME MOUNTAIN DEPOSIT By GERALD W. THORSEN STATII PRINTING PLANT, OLYMPI A, WASH, 1966 For sale by Department of Conservation, Olympia, Washington. Price, $4,50 FOREWORD Since the early days of Washington's statehood, limestone has been recognized as one of the important mineral resources _of the State. The second annual report of the Washington Geological Survey, published in 1903, gave details on the State's limestone deposits, and in later years five other reports published by the Survey and its successor agencies hove given additional information on this resource. Still other reports by Federal and private agencies hove been published in response to demands for data on limestone here. Although some of the earlier reports included analyses to show the purity of the rocks, very few of the samples for analysis were taken systemati cally in a way that would fairly represent the deposits sampled. Prior to 1900 limestone was produced for use as building stone here, and another important use was for the production of burned Ii me . Portland cement plants soon became leading consumers of Ii mestone, and they con tinue as such to the present time . Limestone is used in large quantities in the pulp industry in the Northwest, and in 1966 there was one commercial lime-burning plant in the State. Recognizing the potential for industrial development in Washington based on more intensive use of our mineral resources, and recognizing the need to up-dote the State's knowledge of raw material resources in order to channel those resources into the State's growing economy, the Industrial Row Materials Advisory Committee of the Deportment of Commerce and Economic Development in 1958 recommended that a comprehensive survey be made of the limestone resources of Washington. -

Dec 15, 1999 LAB MANUAL 1209

October 2012 LAB MANUAL 1209.0 1209.0 LITHOLOGICAL SUMMARY 1209.1 GENERAL This test procedure is performed on aggregates to determine the per- centage of various rock types (especially the deleterious varieties) regulated in the Standard Specifications for Construction. 1209.2 APPARATUS A. Dilute Hydrochloric Acid (10% ±) - One part concentrated HCL with 9 parts water and eyedropper applicator B. "Brass Pencil" - (See Section 1218.2 for description) C. Balances - Shall conform to AASHTO M 231 (Classes G2 & G5). Readability & sensitivity 0.1 grams, accuracy 0.1 grams or 0.1%. Balances shall be appropriate for the specific use. D. Small Hammer, Steel Plate and Safety Glasses E. Paper Containers - Approximately 75mm (3") in diameter F. Magnifying Hand Lens (10 to 15 power) G. Unglazed Porcelain Tile (streak plate) 1209.3 TEST SAMPLE The test sample, prepared in accordance with Section 1201.4G, shall be washed (Observe washing restrictions in Section 1201.4G1c) and then dried to a constant weight at a temperature of 110 ± 5 °C (230 ± 9 °F). (See Section 1201, Table 1, for sample weights.) 1209.4 PROCEDURE Examine and classify each rock piece individually. Some rock types may need to be cracked open to identify or determine the identifying properties of the rock. (Always wear safety glasses). The following general guidelines are for informational purposes: • Always break open pieces of soft rock or any others of which you are unsure as the outside is often weathered. • Pick the easy particles first October 2012 LAB MANUAL 1209.4 • Don't be overly concerned about questionable particles unless they will fail the sample. -

University of Nevada Reno (Jreeology of Paleozoic Basinal Rocks in The

i \ University of Nevada Reno (jreeology of Paleozoic Basinal Rocks in the Northern Fox Range; Washoe County, Nevada A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geology. by Mark F. Thiesse V i August 1988 11 MINES LIBRARY The thesis of Mark F. Thiesse is approved: 2H03 Thesis Advisor Department Chairman Dean, Graduate School University of Nevada Reno August 1988 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. R .A. Schweickert for his help, encouragement and patience throughout this project. Dr. Bruce Wardlaw provided the conodont identification which suggested the Carboniferous (?) age of the metamorphic rocks. Other thanks go to Andy Markos and Bob Strobel for help with the thin sections and interesting discussions. And finally, thanks to Carol for typing and for funding this project. iv ABSTRACT The Fox Range in Northwestern Nevada is a typical Basin and Range fault block mountain range which has been tilted about 30° to the east, accelerating the erosion of Tertiary volcanic rocks along the steep western flanks, and exposing Paleozoic metamorphic rocks. The Paleozoic rocks consist of a very fine grained, siliceous mudstone which was regionally metamorphosed from mid-greenschist to mid-amphibolite facies producing argillite, schist, limestone, quartzite, and gneiss. These Paleozoic rocks exhibit three generations of structures. Di created the schistose and gneissic layering common throughout the range, along with abundant tight to isoclinal folds. D2 structures are dominated by two large, map-scale antiforms and occasional smaller, open to tight, east to northeast trending folds and assorted lineations. D3 structures are limited to a few north-south trending, open to gentle folds which affect all pre-Tertiary lithologies. -

Description of the Gold Belt. Geographic Relations

DESCRIPTION OF THE GOLD BELT. GEOGRAPHIC RELATIONS. shore was apparently somewhat west of the Oro and the Mariposa slates, are found only on post-Juratrias upheaval, and that their age, present crest, and the sea extending westward the western flank of the Sierra Nevada. During therefore, is early Cretaceous. The principal gold belt of California includes received Paleozoic sediments which now consti the earlier part of the Juratrias period portions SUPERJACENT SERIES. a portion of the Sierra Nevada lying between the tute a large part of the central portion of the of the Great Basin were under water, as is shown parallels of 37° 30' and 40° north latitude. It is range. by the fossiliferous beds of that age in Eldorado CRETACEOUS PERIOD. bounded on the west by the Sacramento and San At the close of the Carboniferous the Paleozoic Canyon south of Virginia City and in the Hum- Since no beds of early Cretaceous age are Joaquin valleys, and on the east by a diagonal land area of western Nevada subsided, and dur boldt Mountains, but nowhere from the foothills known in the Sierra Nevada, it is presumed that line extending from about longitude 120° 40' in ing the larger part of the Juratrias period it was of the Sierra Nevada to the east base of the during the early Cretaceous all of the present the neighborhood of the fortieth parallel to lon at least partly covered by the sea. At the close Wasatch, if we except certain beds near Genesee range was above water. gitude 119° 40' in the neighborhood of parallel of the Juratrias the Sierra Nevada was upheaved Valley, are any deposits known which are of late During the late Cretaceous the range subsided 37° 30'. -

Geology of the Canadian Rockies and Columbia Mountains Summary by Ben Gadd

Geology of the Canadian Rockies and Columbia Mountains Summary by Ben Gadd 1. Basic geological history of western Canada The evidence reposes in four great layers, each thousands of metres thick. These four great layers (I call them the ancient sediments, the old clastics, the middle carbonates and the young clastics) show two main phases in the geological history of western Canada. First came a long period of sediment deposition, followed by a shorter period of mountain-building. Throughout this time—1.7 billion years altogether—the movement of the world’s crustal plates played a key role. • See last page for the currently accepted geological time scale, with period names and dates. First phase: deposition of most of the rock. About 1.7 billion years ago, part of what is now North America was imbedded in a supercontinent (amalgamation of continents) called Columbia (no relation to the Columbia Mountains). The oldest sedimentary rock in the Rockies was deposited about this time in an inland sea on Columbia. This rock is mostly argillite—very hard mud—and it is now found at the northern end of the Rockies. It is not found in ranges west of the Rockies. The supercontinent of Columbia broke up about 200 million years later. While North America was drifting free some 1.5 billion years ago, a second batch of ancient argillite, with additional limestone and dolostone—more on dolostone in a minute—was deposited in another inland sea, this time at the southern end of the Canadian Rockies in the Waterton area, and to the west in what are now the Purcell Mountains, one of the ranges in the Columbia Mountains (Purcells, Selkirks, Monashees and Cariboos). -

Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology GEOLOGIC MAP of THE

Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MONTANA PART OF THE WALLACE 30' x 60' QUADRANGLE by Jeffrey D. Lonn and Mark D. McFaddan* Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open File Report MBMG 388 1999 This report has had preliminary reviews for conformity with Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology’s technical and editorial standards Partial support has been provided by the STATEMAP component of the National Cooperative Geologic Mapping Program of the U.S. Geological Survey under Contract Number 98-HQ-AG- 2080. *Geology Department, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844 Figure 1. Age correlation of map units. 1 Introduction The Wallace 30' x 60' quadrangle contains structures critical to understanding the tectonic history of western Montana, but the area has been largely neglected by mapping geologists. In 1998, the joint U.S. Geological Survey/Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology STATEMAP project funded new mapping of the Montana portion of the Wallace quadrangle. Although Harrison et al. (1986) had compiled existing mapping (Calkins and Jones, 1912; Wallace and Hosterman, 1956; Campbell, 1960) and added some original mapping at the 1:250,000 scale, we remapped most of the area in an effort to unravel the structural complexities. Lewis et al. (1999) mapped the adjoining Idaho portion of the Wallace quadrangle. Unpublished mapping of some Revett Formation exposures by Appelgate and Lafco (1981) was invaluable in pointing the way towards some key areas. Additionally, structural geology has been well studied in the Coeur d’Alene mining district immediately to the west, and this knowledge has been instrumental in deciphering the geologic history of the Wallace quadrangle. -

USGS Open-File Report OF98-466, Part 4

GEOLOGY OF SEDIMENTARY mineralization into three models, which form a ROCK-HOSTED GOLD DEPOSITS spectrum between undeformed stratabound replacement bodies with little structure, more The deposit-scale geologic structurally controlled orebodies with either characteristics—such as host-structure, host- high-grade vein-like ores, and massive breccia- rock, alteration, and ore minerals for both or stockwork-type (fig. 22). Peters (1996, 1997c) Nevada and Chinese sedimentary rock-hosted has suggested that shear folding of pre-existing gold deposits—are well documented in the regional folds was a major ore-control in the geologic literature (see Christensen, 1993; Liu, large Betze deposit in the Carlin trend and that D.S. and others, 1994; Wang, Y.G. and others, some of the deformation was synchronous with 1994; Bagby and Berger, 1985; Kuehn and Rose, ore deposition. Syn-deformational genesis has 1995; Arehart, 1996). The following discussion also been documented in the Lannigou deposit, outlines these characteristics, and compares the Guizhou Province, by Luo, X.H. (1993, 1996). difference between deposits in P.R. China and Nevada. This discussion also helps us Liu, D.S. and others (1994) identify four understand the difference in geologic main types of host-structure in Chinese characteristics between Carlin-type and other sedimentary rock-hosted gold deposits. These type of gold deposits that are directly related to are: (1) short-axial anticlines; (2) stratabound igneous and metamorphic activity. breccia bodies; (3) unconformity surfaces; and (4) joints associated with faults and anticlines. Shear zones with ductile-brittle deformation Host Structures and Feeder Systems textures of ore and rocks also are observed in some Chinese sedimentary rock-hosted gold World-wide distribution of Carlin-type deposits (figs. -

USGS MF-2336, Explanation

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS MISCELLANEOUS FIELD STUDIES MF-2336 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SHEET 5 OF 6, Version 1.0 QUATERNARY AND TERTIARY Pamphlet accompanies map COAST RANGES PROVINCE OVERLAP DEPOSITS DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS The Yager terrane locally includes: ecsp Serpentinite melange-Scarce blocks up to 500 m long, of basalt, Ycgl Conglomerate-Polymict, well rounded, consisting largely of recycled diabase, gabbro, and ophiolitic breccia in a sheared matrix of serpentinized Holocene 125¡ Qt Qls 41¡ QUATERNARY AND TERTIARY OVERLAP DEPOSITS clasts. Clasts commonly include abundant hypabyssal volcanic and plutonic dunite and minor harzburgite; locally may include small intrusive bodies of FRANCISCAN COMPLEX Qal 124¡ rocks of granitic to dioritic composition; and less common metaclastic rocks diorite and quartz diorite. At Red Lassic, northeast of Zenia (Sheet 3), Qm MAD RIVER Figure 3. Generalized map showing principal faults and folds discussed in the map area, (including black or green radiolarian chert, quartzite, metasandstone and includes a large block of pillow basalt flows and flow breccia with area of active Mendocino uplift (stippled pattern), and major plates. Map units delineated Qal Alluvial deposits (Holocene and late Pleistocene?)-Clay, silt, sand, gravel, Pleistocene QUATERNARY metaconglomerate) interleaved chert having Upper Jurassic (Tithonian) radiolarian assemblage locally for purposes of location include: Neogene overlap deposits (QTw), Coast Ranges and boulders, deposited in stream beds, alluvial fans, terraces, flood plains Coastal Belt QTog (cr), King Range (kr), Yager terrane (y), False Cape terrane (fc), Central belt (cb), Yolla Central belt (table 1 and fig. 3, Loc. 79; Kaplan, 1983; 1984). -

GEOLOGIC MAP of the LINE POINT QUADRANGLE, BOUNDARY COUNTY, IDAHO, and Tion by Cominco (Hamilton and Others, 2000)

IDAHO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY IDAHOGEOLOGY.ORG IGS DIGITAL WEB MAP 150 MONTANA BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MBMG.MTECH.EDU MBMG OPEN FILE 623 white graded or nongraded argillite tops. Conspicuous bar code-like REFERENCES patterns in the middle, formed by alternating dark and light siltite, persist regionally (Huebschman, 1973) and have been used as markers for correla- GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE LINE POINT QUADRANGLE, BOUNDARY COUNTY, IDAHO, AND tion by Cominco (Hamilton and others, 2000). Siltite and argillite couplets, Anderson, H.E., and D.W. Davis, 1995, U-Pb geochronology of the Moyie sills, with dark, less commonly light tops, have even and parallel, uneven, wavy Purcell Supergroup, southeastern British Columbia: Implications for the or undulating lamination. Rusty nature of outcrop is due to weathering of Mesoproterozoic geological history of the Purcell (Belt) basin: Canadian CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS abundant sulfides, commonly pyrrhotite. Dominant lamination style and Journal of Earth Sciences, v. 32, no. 8, p. 1180-1193. LINCOLN COUNTY, MONTANA concentration of sulfides vary between members. Quartzite in 2-20 dm beds Anderson, H.E., and W.D. Goodfellow, 2000, Geochemistry and isotope chem- Alluvial and Colluvium and Glacial and Related Deposits is light weathering, averages about 60 percent quartz, 20 percent plagio- istry of the Moyie sills: Implications for the early tectonic setting of the Lacustrine Deposits Mass Wasting Deposits clase, with the rest mostly white micas and 5 percent biotite (Cressman, Mesoproterozoic Purcell basin, in J.W. Lydon, Trygve Höy, J.F. Slack, and 1989). Previous mapping in this area and to the east by Cressman and Harri- M.E.