"In Motion" Mckenzie Dial Eastern Illinois University This Research Is a Product of the Graduate Program in English at Eastern Illinois University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIKE JOY Race Announcer, FOX NASCAR

MIKE JOY Race Announcer, FOX NASCAR Broadcasting veteran Mike Joy brings 50 years of motor sports experience to the booth as lead race announcer for FOX NASCAR in 2020, his 20th consecutive season with the network, alongside NASCAR Hall of Famer Jeff Gordon. Joy has led the network’s broadcast team since 2001, FOX’s first year as a NASCAR broadcast partner. Joy has broadcast most major forms of American motorsports for television and radio. Prior to joining FOX in 2001, Joy anchored CBS Sports’ coverage of the DAYTONA 500 from 1998-2000 after earning his stripes as a pit reporter for 15 years. In addition, Joy called the “Great American Race” for Motor Racing Network (MRN) Radio from 1977-’83 (as a turn announcer and anchor). The season-opening DAYTONA 500 marks the 41st DAYTONA 500 for which he has been part of live TV or radio coverage. In 2020, Joy covers his 45th Daytona Speedweeks. He is a charter member of the prestigious NASCAR Hall of Fame Voting Panel, and in December 2013, was named sole media representative on the Hall's exclusive Nominating Committee. Joy previously served on the voting panel for the International Motorsports Hall of Fame. Joy was the 2011 recipient of the esteemed Henry T. McLemore Motorsports Journalism Award, recognizing career excellence in the field, as well as the 2018 North Carolina Motorsports Association (NCMA) Jim Hunter Memorial Media Award. A former vice president of the National Motorsport Press Association, Joy joined Chris Economaki as the first racing journalists to receive major recognition for their work in all three major disciplines: radio, television and print. -

Daytona 500 Coverage Live on Siriusxm

NEWS RELEASE Daytona 500 Coverage Live on SiriusXM 2/12/2018 Fans nationwide get live broadcast of 60th Daytona 500 on Feb. 18 Extensive coverage from the track on race day and throughout Speedweeks on SiriusXM NASCAR Radio Kevin Harvick hosts his show, "Happy Hours," live from Daytona on Feb. 14 NEW YORK, Feb. 12, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- SiriusXM will offer the most comprehensive audio coverage of the 60th running of the Daytona 500 on February 18, as well as all the news and events of NASCAR's anticipated Speedweeks leading up to race day. Subscribers nationwide will have access to the live race broadcast, in-car audio from some of the sport's top drivers, and daily coverage from Daytona International Speedway. On Daytona 500 race day, SiriusXM will offer 15 hours of live programming from the speedway starting at 7:00 am ET. Subscribers will hear every turn of the "The Great American Race" (green flag approximately 2:30 pm ET) plus full pre- and post-race coverage with expert analysis, reports from pit road and the garages, driver introductions and interviews with the race winner and other drivers. The programming airs on the exclusive 24/7 SiriusXM NASCAR Radio channel (ch. 90). Go to www.SiriusXM.com/NASCAR for more info. SiriusXM NASCAR Radio will also provide live coverage of the Can-Am Duel, the 150-mile Monster Energy NASCAR Cup Series qualifying races, on Thursday, Feb. 15 (6:00 pm ET), the NextEra Energy Resources 250 NASCAR Camping World Truck Series race on Friday, Feb. 16 (7:00 pm ET), and the Power Shares QQQ 300 NASCAR Xfinity Series race on Saturday, Feb. -

FOX NASCAR at MONSTER ENERGY ALL-STAR RACE at Charlotte Motor Speedway Quotes & Programming Schedule

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Megan Englehart Tuesday, May 16, 2017 [email protected] FOX NASCAR AT MONSTER ENERGY ALL-STAR RACE AT CHARLOTTE MOTOR SPEEDWAY QUOTES & PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE MONSTER ENERGY ALL-STAR RACE, MONSTER ENERGY OPEN & NASCAR CAMPING WORLD TRUCK SERIES Live on FS1 under the Lights Key Players Larry McReynolds & Mike Joy Recall 1992 “One Hot Night” 25 Years Later CHARLOTTE, N.C. – It’s all about the trophy and the $1 million winner’s bonus in this weekend’s MONSTER ENERGY ALL-STAR RACE at Charlotte Motor Speedway, which celebrates the 25th anniversary of the iconic 1992 race dubbed “One Hot Night” this year. FOX Sports is set to offer 16 hours of live action from the 1.5-mile circuit, which, in 1992, became the first superspeedway to light the entire track. Included are FS1’s live race coverage of the MONSTER ENERGY ALL-STAR RACE (Saturday, May 20 at 8:00 PM ET), the MONSTER ENERGY OPEN last-chance qualifier (Saturday, May 20 at 6:00 PM ET) and the NASCAR CAMPING WORLD TRUCK SERIES (Friday, May 19 at 8:30 PM ET). ARCA RACING SERIES: Stock car action continues on Sunday from Ohio, when FS1 offers a delayed broadcast of the ARCA RACING SERIES race from Toledo Speedway at 5:00 PM ET. NASCAR RACE HUB: During the week, FS1’s NASCAR RACE HUB, NASCAR’s most-watched daily news and information program, continues Mondays through Thursdays at 6:00 PM ET. On Wednesday, May 17, Clint Bowyer is in-studio as a driver analyst. -

Brown's Memorial Funeral Home

Wonder of Water Festival - Page 6 the Irving Rambler www.irvingrambler.com “The Newspaper Irving Reads” May 18, 2006 Comics Page 11 Art Association THIS Classifieds Page 11 Pirouettes host Obituaries Page 8 celebrates 50 years championships Police & Fire Page 2 WEEK Puzzles Page 10 Page 3 Page 7 Gov. Perry signs landmark business tax reform Gov. Rick Perry traveled to KB employers, reliable funding for our Troy Fraser, R-Marble Falls, also at- Home Studio in Irving to sign into school classrooms and revenue tended the bill signing. law House Bill 3, legislation that that will help deliver a record $15.7 Perry noted that the old tax provides comprehensive business billion property tax cut for the system has gaping loopholes that tax reform but also helps deliver the people of Texas,” Perry said. allows businesses with good ac- largest property tax cut in the state’s Perry thanked state Rep. Jim countants to avoid paying their history. Keffer, R-Eastland, who authored share while other employers got “Today I am proud to sign into the legislation and participated in stuck carrying an unfair tax load and law landmark business tax reforms the bill signing, for shepherding the schools struggled as revenue from that will provide greater fairness for bill through the Texas House. Sen. the business tax steadily dwindled... and millions of homeowners who have been forced ElectionElection fafavorsvors incumbentsincumbents to make up the difference with sky- rocketing local property taxes. “When I put my signature on House Bill 3, that will all change,” he said. “Employers will benefit with a tax system that is fairer, a tax base that is broader and a tax rate that is substantially lower than the one we Providing for Texas’ public schools, Governor Perry addresses the have today. -

Fox Sports Highlights – 3 Things You Need to Know

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, Sept. 17, 2014 FOX SPORTS HIGHLIGHTS – 3 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW NFL: Philadelphia Hosts Washington and Dallas Meets St. Louis in Regionalized Matchups COLLEGE FOOTBALL: No. 4 Oklahoma Faces West Virginia in Big 12 Showdown on FOX MLB: AL Central Battle Between Tigers and Royals, Plus Dodgers vs. Cubs in FOX Saturday Baseball ******************************************************************************************************* NFL DIVISIONAL MATCHUPS HIGHLIGHT WEEK 3 OF THE NFL ON FOX The NFL on FOX continues this week with five regionalized matchups across the country, highlighted by three divisional matchups, as the Philadelphia Eagles host the Washington Redskins, the Detroit Lions welcome the Green Bay Packers, and the San Francisco 49ers play at the Arizona Cardinals. Other action this week includes the Dallas Cowboys at St. Louis Rams and Minnesota Vikings at New Orleans Saints. FOX Sports’ NFL coverage begins each Sunday on FOX Sports 1 with FOX NFL KICKOFF at 11:00 AM ET with host Joel Klatt and analysts Donovan McNabb and Randy Moss. On the FOX broadcast network, FOX NFL SUNDAY immediately follows FOX NFL KICKOFF at 12:00 PM ET with co-hosts Terry Bradshaw and Curt Menefee alongside analysts Howie Long, Michael Strahan, Jimmy Johnson, insider Jay Glazer and rules analyst Mike Pereira. SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 21 GAME PLAY-BY-PLAY/ANALYST/SIDELINE COV. TIME (ET) Washington Redskins at Philadelphia Eagles Joe Buck, Troy Aikman 24% 1:00PM & Erin Andrews Lincoln Financial Field – Philadelphia, Pa. MARKETS INCLUDE: Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Washington, Miami, Raleigh, Charlotte, Hartford, Greenville, West Palm Beach, Norfolk, Greensboro, Richmond, Knoxville Green Bay Packers at Detroit Lions Kevin Burkhardt, John Lynch 22% 1:00PM & Pam Oliver Ford Field – Detroit, Mich. -

Behind the Scenes: COVID-19 Consequences on Broadcast Sports Production

International Journal of Sport Communication, 2020, 13, 484–493 https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2020-0231 © 2020 Human Kinetics, Inc. SCHOLARLY COMMENTARY Behind the Scenes: COVID-19 Consequences on Broadcast Sports Production Roxane Coche and Benjamin J. Lynn University of Florida Live events are central to television production. Live sporting events, in particular, reliably draw big audiences, even though more consumers unsubscribe from cable to stream content on-demand. Traditionally, the mediated production of these sporting events have used technical and production crews working together on- site at the event. But technological advances have created a new production model, allowing the production crew to cover the event from a broadcast production hub, miles away, while the technical crew still works from the event itself. These remote integration model productions have been implemented around the world and across all forms of sports broadcasting, following a push for economic efficiency—fundamental in a capitalist system. This manu- script is a commentary on the effects of the COVID-19 global crisis on sports productions, with a focus on remote integration model productions. More specifically, the authors argue that the number of remote sports productions will grow exponentially faster, due to the pandemic, than they would have under normal economic circumstances. The consequences on sport media education and research are further discussed, and a call for much needed practice-based sports production research is made. Keywords: education, live sports, REMI NASCAR (the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing) returned to racing in Darlington, South Carolina, on May 17, 2020, more than 2 months after the last pre-COVID-19 event, on March 8. -

Super Bowl XLVIII on FOX Broadcast Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 PHOTOGRAPHY 2 FOX SUPER BOWL SUNDAY BROADCAST SCHEDULE 3-6 SUPER BOWL WEEK ON FOX SPORTS 1 TELECAST SCHEDULE 7-10 PRODUCTION FACTS 11-13 CAMERA DIAGRAM 14 FOX SPORTS AT SUPER BOWL XLVIII FOXSports.com 15 FOX Sports GO 16 FOX Sports Social Media 17 FOX Sports Radio 18 FOX Deportes 19-21 SUPER BOWL AUDIENCE FACTS 22-23 10 TOP-RATED PROGRAMS ON FOX 24 SUPER BOWL RATINGS & BROADCASTER HISTORY 25-26 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 27 SUPERBOWL CONFERENCE CALL HIGHLIGHTS 28-29 BROADCASTER, EXECUTIVE & PRODUCTION BIOS 30-62 MEDIA INFORMATION The Super Bowl XLVIII on FOX broadcast guide has been prepared to assist you with your coverage of the first-ever Super Bowl played outdoors in a northern locale, coming Sunday, Feb. 2, live from MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, NJ, and it is accurate as of Jan. 22, 2014. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to assist you with the latest information, photographs and interview requests as needs arise between now and game day. SUPER BOWL XLVIII ON FOX CONFERENCE CALL SCHEDULE CALL-IN NUMBERS LISTED BELOW : Thursday, Jan. 23 (1:00 PM ET) – FOX SUPER BOWL SUNDAY co-host Terry Bradshaw, analyst Michael Strahan and FOX Sports President Eric Shanks are available to answer questions about the Super Bowl XLVIII pregame show and examine the matchups. Call-in number: 719-457-2083. Replay number: 719-457-0820 Passcode: 7331580 Thursday, Jan. 23 (2:30 PM ET) – SUPER BOWL XLVIII ON FOX broadcasters Joe Buck and Troy Aikman, Super Bowl XLVIII game producer Richie Zyontz and game director Rich Russo look ahead to Super Bowl XLVIII and the network’s coverage of its seventh Super Bowl. -

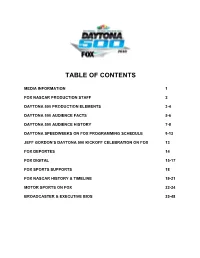

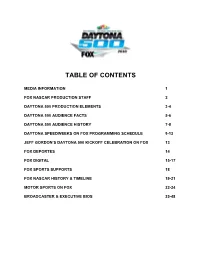

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

Racing, Region, and the Environment: a History of American Motorsports

RACING, REGION, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: A HISTORY OF AMERICAN MOTORSPORTS By DANIEL J. SIMONE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Daniel J. Simone 2 To Michael and Tessa 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A driver fails without the support of a solid team, and I thank my friends, who supported me lap-after-lap. I learned a great deal from my advisor Jack Davis, who when he was not providing helpful feedback on my work, was always willing to toss the baseball around in the park. I must also thank committee members Sean Adams, Betty Smocovitis, Stephen Perz, Paul Ortiz, and Richard Crepeau as well as University of Florida faculty members Michael Bowen, Juliana Barr, Stephen Noll, Joseph Spillane, and Bill Link. I respect them very much and enjoyed working with them during my time in Gainesville. I also owe many thanks to Dr. Julian Pleasants, Director Emeritus of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, and I could not have finished my project without the encouragement provided by Roberta Peacock. I also thank the staff of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program. Finally, I will always be grateful for the support of David Danbom, Claire Strom, Jim Norris, Mark Harvey, and Larry Peterson, my former mentors at North Dakota State University. A call must go out to Tom Schmeh at the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame, Suzanne Wise at the Appalachian State University Stock Car Collection, Mark Steigerwald and Bill Green at the International Motor Racing Resource Center in Watkins Glen, New York, and Joanna Schroeder at the (former) Ethanol Promotion and Information Council (EPIC). -

Nascar Race Hub Danielle Trotta

Nascar race hub danielle trotta Continue Real nameDaniel TrottaImtsday3-13-1981Westchester County, New York'diac SignPiscesNationalityAmericanEthnicityCaucasianProfessionSports ReporterMarried/HusbandRobby BentonSalary/IncomeUnder ReviewNet Worth$2 MillionParentsDan Trotta, Phyllis TrottaSiblingsAndrea Trotta celebrates his birthday on March 13, born in 1981. She grew up in Westchester County, New York. She is American by nationality and ethnicity is Caucasian. She attended Carmel High School and then went on to pursue her college degree at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte. She graduated from the Faculty of Mass Communications. Danielle Trotta with her colleague After completing her education, she worked as a weekend news editor for WBTV. In 2007, she made her screen debut and later hosted Sports on Saturday Night. She is also one of the organizers of Point after with D.D. Her hard work has helped her achieve a good position in the journalism industry. At her career duration, she covered high school athletes who pressed opportunities on playing ground. She also worked on various television stations as a reporter, including FOX Sports, NASCAR and ESPN 730. However, she later joined NBC Sports Boston. She worked at various stations that eventually helped her embellished fame and prestige from her career. Her profession has helped her enjoy a luxurious lifestyle. Trotta's net worth is expected to be $2 million. After being in a committed relationship, Trotta married her longtime friend, Robbie Benton. Her husband proposed to her at the Cathedral of Monaco. The couple exchanged wedding vows on October 27, 2018. Together the couple is happy with their family life and shares intimate moments on their social networks. -

Daytona 500 Audience History ______17

Table of Contents Media Information ____________________________________________________2 Photography _________________________________________________________3 Production Staff ______________________________________________________4 Production Details __________________________________________________5 - 6 Valentine’s Day Daytona 500 Tale of the Tape _____________________________ 7 FOXSports.com at Daytona_____________________________________________ 8 NASCAR ON FOX Social Media _________________________________________ 9 Fox Sports Radio at Daytona _______________________________________10 – 11 FOX Sports Supports: Ronald McDonald House ___________________________12 NASCAR on FOX: 10th Season & Schedule ____________________________ 13-14 Daytona 500 & Sprint Cup Audience Facts____________________________ 15 - 16 Daytona 500 Audience History _________________________________________17 Broadcaster Biographies ___________________________________________18-27 MEDIA INFORMATION This guide has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of the Daytona 500 on FOX and is accurate as of Feb. 8, 2010. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information, photographs and facilitate interview requests. NASCAR on FOX photography, featuring Darrell Waltrip, Larry McReynolds, Mike Joy, Jeff Hammond, Chris Myers, Dick Berggren, Steve Byrnes, Krista Voda and Matt Yocum, is available on FOXFlash.com. Releases on FOX Sports’ NASCAR programming are available on www.msn.foxsports.com