Times & Sounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classic Albums: the Berlin/Germany Edition

Course Title Classic Albums: The Berlin/Germany Edition Course Number REMU-UT 9817 D01 Spring 2019 Syllabus last updated on: 23-Dec-2018 Lecturer Contact Information Course Details Wednesdays, 6:15pm to 7:30pm (14 weeks) Location NYU Berlin Academic Center, Room BLAC 101 Prerequisites No pre-requisites Units earned 2 credits Course Description A classic album is one that has been deemed by many —or even just a select influential few — as a standard bearer within or without its genre. In this class—a companion to the Classic Albums class offered in New York—we will look and listen at a selection of classic albums recorded in Berlin, or recorded in Germany more broadly, and how the city/country shaped them – from David Bowie's famous Berlin trilogy from 1977 – 79 to Ricardo Villalobos' minimal house masterpiece Alcachofa. We will deconstruct the music and production of these albums, putting them in full social and political context and exploring the range of reasons why they have garnered classic status. Artists, producers and engineers involved in the making of these albums will be invited to discuss their seminal works with the students. Along the way we will also consider the history of German electronic music. We will particularly look at how electronic music developed in Germany before the advent of house and techno in the late 1980s as well as the arrival of Techno, a new musical movement, and new technology in Berlin and Germany in the turbulent years after the Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, up to the present. -

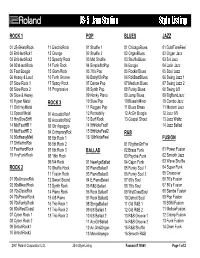

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

"World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 17:23 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump Canadian Perspectives in Ethnomusicology Résumé de l'article Perspectives canadiennes en ethnomusicologie This article traces the origins and uses of the musical classifications "world Volume 19, numéro 2, 1999 music" and "world beat." The term "world beat" was first used by the musician and DJ Dan Del Santo in 1983 for his syncretic hybrids of American R&B, URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014442ar Afrobeat, and Latin popular styles. In contrast, the term "world music" was DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar coined independently by at least three different groups: European jazz critics (ca. 1963), American ethnomusicologists (1965), and British record companies (1987). Applications range from the musical fusions between jazz and Aller au sommaire du numéro non-Western musics to a marketing category used to sell almost any music outside the Western mainstream. Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Klump, B. (1999). Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 19(2), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1999 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Effets & Gestes En Métropole Toulousaine > Mensuel D

INTRAMUROSEffets & gestes en métropole toulousaine > Mensuel d’information culturelle / n°383 / gratuit / septembre 2013 / www.intratoulouse.com 2 THIERRY SUC & RAPAS /BIENVENUE CHEZ MOI présentent CALOGERO STANISLAS KAREN BRUNON ELSA FOURLON PHILLIPE UMINSKI Éditorial > One more time V D’après une histoire originale de Marie Bastide V © D. R. l est des mystères insondables. Des com- pouvons estimer que quelques marques de portements incompréhensibles. Des gratitude peuvent être justifiées… Au lieu Ichoses pour lesquelles, arrivé à un certain de cela, c’est souvent l’ostracisme qui pré- cap de la vie, l’on aimerait trouver — à dé- domine chez certains des acteurs culturels faut de réponses — des raisons. Des atti- du cru qui se reconnaîtront. tudes à vous faire passer comme étranger en votre pays! Il faut le dire tout de même, Cependant ne généralisons pas, ce en deux décennies d’édition et de prosély- serait tomber dans la victimisation et je laisse tisme culturel, il y a de côté-ci de la Ga- cet art aux politiques de tous poils, plus ha- ronne des décideurs/acteurs qui nous biles que moi dans cet exercice. D’autant toisent quand ils ne nous méprisent pas tout plus que d’autres dans le métier, des atta- simplement : des organisateurs, des musi- ché(e)s de presse des responsables de ciens, des responsables culturels, des théâ- com’… ont bien compris l’utilité et la néces- treux, des associatifs… tout un beau monde sité d’un média tel que le nôtre, justement ni qui n’accorde aucune reconnaissance à inféodé ni soumis, ce qui lui permet une li- photo © Lisa Roze notre entreprise (au demeurant indépen- berté d’écriture et de publicité (dans le réel dante et non subventionnée). -

SCORPIONS Lovedrive (Hard Rock)

SCORPIONS Lovedrive (Hard Rock) Année de sortie : 1979 Nombre de pistes : 8 Durée : 37' Support : CD Provenance : Acheté Nous avons décidé de vous faire découvrir (ou re découvrir) les albums qui ont marqué une époque et qui nous paraissent importants pour comprendre l'évolution de notre style préféré. Nous traiterons de l'album en le réintégrant dans son contexte originel (anecdotes, etc.)... Une chronique qui se veut 100% "passionnée" et "nostalgique" et qui nous l'espérons, vous fera réagir par le biais des commentaires ! Bon voyage ! Avec Lovedrive, SCORPIONS entame la plus extraordinaire trilogie discographique jamais enregistrée par un groupe de Rock allemand. Sans doute est-ce dû au succès rencontré par la tournée mondiale d’où fut tiré le splendide live Tokyo Tapes et qui a enfin apporté une crédibilité internationale aux arthropodes.Sans doute également l’intégration du jeune guitariste Matthias JABS (remplaçant l’excentrique Uli John ROTH, parti fonder ELECTRIC SUN, bien que l’on ressente encore parfois son apport musical) a-t-elle eu une influence sur le résultat final. Sans doute, encore, est-ce le fait de changer de label, passant de RCA à EMI. Sans doute, enfin, que la nationalité même du groupe fut un rempart contre le Punk qui a dévasté les plus grands noms de l’époque. Les conseils du producteur Dieter DIERKS expliquent également certainement le succès fulgurant remporté par ce cinquième album studio des SCORPIONS. Tout autant que la pochette (signée par l’avant-gardiste Hipgnosis) qui, une nouvelle fois (après celle fort décriée et aujourd’hui introuvable de Virgin Killer) fait jaser. -

Music on PBS: a History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station

Music on PBS: A History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station Rochelle Lade (BArts Monash, MArts RMIT) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2021 Abstract This historical case study explores the programs broadcast by Melbourne community radio station PBS from 1979 to 2019 and the way programming decisions were made. PBS has always been an unplaylisted, specialist music station. Decisions about what music is played are made by individual program announcers according to their own tastes, not through algorithms or by applying audience research, music sales rankings or other formal quantitative methods. These decisions are also shaped by the station’s status as a licenced community radio broadcaster. This licence category requires community access and participation in the station’s operations. Data was gathered from archives, in‐depth interviews and a quantitative analysis of programs broadcast over the four decades since PBS was founded in 1976. Based on a Bourdieusian approach to the field, a range of cultural intermediaries are identified. These are people who made and influenced programming decisions, including announcers, program managers, station managers, Board members and the programming committee. Being progressive requires change. This research has found an inherent tension between the station’s values of cooperative decision‐making and the broadcasting of progressive music. Knowledge in the fields of community radio and music is advanced by exploring how cultural intermediaries at PBS made decisions to realise eth station’s goals of community access and participation. ii Acknowledgements To my supervisors, Jock Given and Ellie Rennie, and in the early phase of this research Aneta Podkalicka, I am extremely grateful to have been given your knowledge, wisdom and support. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Roedelius Bio Engl

ROEDELIUS: JARDIN AU FOU CD and Vinyl Release date: March 27th 2009 Cat No BB23 CD 927892/LP 927891 The essentials: ► Hans-Joachim Roedelius: born 1934; first record release in 1969 with Kluster (with Dieter Moebius and Konrad Schnitzler), and active ever since as a solo artist and in various collaborations (amongst others with Moebius/Cluster, Moebius and Michael Rother/Harmonia, as well as with Brian Eno). One of the most prolific musicians of the German avant-garde and a key figure in the birth of Krautrock, synthesizer pop and ambient music. ► Jardin au Fou was first released on the French EGG label in 1979 ► produced by Peter Baumann (Tangerine Dream) ► liner notes by Asmus Tietchens ► CD features six bonus tracks: three remixes, three new tracks One of the most remarkable albums of the so-called Krautrock scene has to be Jardin au Fou by Hans-Joachim Roedelius (Cluster, Harmonia), issued in 1979. All the more noteworthy as it bore no resemblance whatsoever to what was expected of avant-garde electronica and displayed none of the typical Krautrock characteristics. Rhythm machine, sequencer and abstract sounds are conspicuous by their absence. Indeed, listeners were stunned by one of the most beautiful, charming, ethereal and peaceful albums in the history of German rock music. It was produced by Peter Baumann at his own Paragon Studios in 1978, a year after he left Tangerine Dream to concentrate on a solo career and production work. At the time, he was charged by the French label EGG with delivering three productions from the German electro/avant- garde/Krautrock cosmos. -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

Music 3500: American Music This Final Exam Is Comprehensive —It Covers the Entire Course (Monday December Starting at 5PM In

FINAL EXAM STUDY GUIDE Music 3500: American Music This final exam is comprehensive —it covers the entire course (Monday December starting at 5PM in Knauss Hall 2452) Exam Format: 70 questions (each question is worth 4 points), plus a 40-point "fill-in-the-chart" (described below) (these two things total a maximum of 320 possible points toward your final course grade total). The format of the 70-question computer-graded section of the final exam will be: ...Matching ...Multiple Choice ...True/False (from text readings, class lectures, YouTube video links) General study recommendations: - Do the online quiz assignments for Chapters 1-9 (these must be completed by Monday April 24) ---------- For the Computer-Graded part of the final exam: 1. Know the definitions of Important Terms at the ends of Chapters 2-8 - Chapter 1 (textbook, page 5) -- know "popular music," "roots music," "Classical art- music" - Chapter 2 (textbook, page 19) -- know "old-time music," "hot jazz," "race music" - Chapter 3 (textbook, page 31) -- know "bebop," "big-band," "boogie-woogie" - Chapter 4 (textbook, page 42) -- know "backbeat," "chance music," "cool jazz," "multi- serialism," "rhythm & blues," "soul" - Chapter 5 (textbook, page 52) -- know "soundtrack," "free jazz" - Chapter 6 (textbook, pages 58-59) -- know "fusion," minimalism," - Chapter 7 (textbook, pages 69-70) -- know "techno," "smooth jazz," "hip-hop" - Chapter 8 (textbook, page 81) -- know "sound art" 2. Know which decade the following music technologies came from: (Review the chronological order of -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC).