The Renaissance of the J Class Yachts.D…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shipbreaking # 43 – April 2016

Shipbreaking Bulletin of information and analysis on ship demolition # 43, from January 1 to 31 March 31, 2016 April 29, 2016 Content Novorossiysk, the model harbour 1 Overview : 1st quarter 2016 11 Bulk carrier 46 Ports : the Top 5 2 Factory ship / fishing ship 13 Cement carrier 76 Ships aground and cargoes adrift 2 Reefer 14 Car carrier 77 In the spotlight 5 Offshore 15 Ro Ro 80 Yellow card and red card for grey ships 6 General cargo 19 Ferry 80 From Champagne to the blowtorch 8 Container ship 30 The END : Italy is breaking 82 Tsarev the squatter 9 Tanker 42 up migrant carriers The disgrace of German ship-owners 9 Chemical tanker 45 Sources 85 Dynamite in Indonesia 10 Gas tanker 45 Novorossiysk (Black Sea, Russia), the model harbour 1 Novorossiysk : detentionstorm in the Black Sea The port of Novorossiysk plays in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean a major role of watchdog. The Russian port has a long tradition in the control of merchant vessels. Within the framework of international agreements on maritime transport safety, inspectors note aboard deficiencies relating to maritime security, protection of the environment and living conditions of crews and do not hesitate to retain substandard ships as much as necessary. Of the 265 ships to be broken up between January 1st and March 31 2016, 14 were detained in Novorossiysk, sometimes repeatedly, and therefore reported as hazardous vessels to all states bordering the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. At least 4 freighters, the Amina H, the Majed and Randy, the Venedikt Andreev and the Med Glory had the migrant carriers profile. -

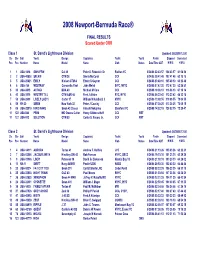

ORR Results Printout

2008 Newport-Bermuda Race® FINAL RESULTS Scored Under ORR Class 1 St. David's Lighthouse Division Updated: 06/28/08 12:00 Cls Div Sail Yacht Design Captain(s) Yacht Yacht Finish Elapsed Corrected Pos Pos Number Name Model Name Club Status Date/Time ADT H M S H M S 1 1 USA-1818 SINN FEIN Cal 40 Peter S. Rebovich Sr. Raritan YC 6/24/08 22:43:57 104 43 57 61 06 38 2 2 USA-40808 SELKIE CTM 38 Sheila McCurdy CCA 6/24/08 20:41:48 102 41 48 62 10 18 3 5 USA-20621 EMILY Nielsen CTM 44 Edwin S Gaynor CCA 6/24/08 23:48:10 105 48 10 63 23 48 4 6 USA-754 WESTRAY Concordia Yawl John Melvin IHYC, NYYC 6/25/08 07:47:20 113 47 20 63 25 51 5 30 USA-3815 ACTAEA BDA 40 Michael M Cone CCA 6/25/08 10:36:13 116 36 13 67 18 14 6 43 USA-3519 WESTER TILL CTM A&R 48 Fred J Atkins EYC, NYYC 6/25/08 06:22:42 112 22 42 68 32 18 7 58 USA-2600 LIVELY LADY II Carter 37 William N Hubbard, III NYYC 6/25/08 13:08:55 119 08 55 70 04 55 8 59 NY-20 SIREN New York 32 Peter J Cassidy CCA 6/25/08 07:38:25 113 38 25 70 05 15 9 86 USA-32510 HIRO MARU Swan 43 Classic Hiroshi Nakajima Stamford YC 6/25/08 14:02:15 120 02 15 73 25 47 11 122 USA-844 PRIM MO Owens Cutter Henry Gibbons-Neff CCA RET 11 122 USA-913 SOLUTION CTM 50 Carter S. -

Download Our 2021-22 Media Pack

formerly Scuttlebutt Europe 2021-22 1 Contents Pages 3 – 9 Seahorse Magazine 3 Why Seahorse 4 Display (Rates and Copy Dates) 5 Technical Briefing 6 Directory 7 Brokerage 8 Race Calendar 9 New Boats Enhanced Entry Page 10 “Planet Sail” On Course show Page 11 Sailing Anarchy Page 12 EuroSail News Page 13 Yacht Racing Life Page 14 Seahorse Website Graeme Beeson – Advertising Manager Tel: +44 (0)1590 671899 Email: [email protected] Skype: graemebeeson 2 Why Seahorse? Massive Authority and Influence 17,000 circulation 27% SUBS 4% APP Seahorse is written by the finest minds 14% ROW & RETAIL DIGITAL PRINT and biggest names of the performance 5,000 22% UK 28% IRC sailing world. 4,000 EUROPE 12% USA 3,000 International Exclusive Importance Political Our writers are industry pro's ahead of and Reach Recognition 2,000 journalists - ensuring Seahorse is the EUROPE A UK S UK 1,000 EUROPE U 14% RORC last word in authority and influence. ROW A A S ROW UK S ROW U 0 U ROW EUROPE IRC ORC RORC SUBS & APP 52% EUROPE (Ex UK) 27% ORC Seahorse is written assuming a high RETAIL SUBS level of sailing knowledge from it's The only sailing magazine, written Recognised by the RORC, IRC & from no national perspective, entirely ORC all of whom subscribe all readership - targetting owners and dedicated to sailboat racing. An their members and certificate afterguard on performance sailing boats. approach reflected by a completely holders to Seahorse as a benefit international reach adopt and adapt this important information into their design work. -

Emirates Team New Zealand and the America's

Emirates Team New Zealand and the America’s Cup A real life context for STEM and innovative technology Genesis is proud to be supporting Emirates Team New Zealand as they work towards defending the 36th America’s Cup, right here in Auckland, New Zealand. Both organisations are known for their creative innovation and design solutions, so together they’ve developed sailing themed resources for the School-gen programme to inspire the next generation of Kiwi scientists, sailors, innovators and engineers. Overview These PDF posters, student worksheets, Quizzz quiz and teacher notes provide an introduction to: • A history of the America’s Cup • The history of sailing • How Genesis is powering Emirates Team New Zealand The resources described in the teacher notes are designed to complement the America’s Cup Trophy experience brought to schools by Genesis. Curriculum links: LEARNING AREAS LEVELS YEARS Science: Above: Physical World Emirates Team Physical inquiry and physics 3-4 5-8 New Zealand visit concepts Arahoe School Nature of Science: Communicating in Science Technology: Nature of Technology Characteristics of Technology 3-4 5-8 Technological Knowledge: Technological products @ Genesis School-gen Teacher information Learning sequence Introducing Explore and Create and Reflect and Make a difference knowledge investigate share extend Learning intentions Students are learning to: • explain how sailing technology has evolved over time • investigate solar power technology and energy • explore the history of the America’s Cup races and the America’s -

The Canada's Cup Years

The Canada i!ii Cup Years ~m 31 THE ROCHESTER YACHT CLUB " 1877 - 2000 Th~ time the Chicago Yacht Club, Columbia Yacht Club of Chicago, 10( THE TURN OF THE ~wo Detroit Cltlbs, alld tile Rocheste, Yacht Club had ,11ade their bids. It was thought fair to give an American Lake Ontario yach! CENTURY c,<,b the preference and RYC won. The years between the founding of Rochester Yacht Club in 1902 1877 and about 1910 are described as Golden Years. Membership had grown froln the original 46 charter members to Each club built one boat under a new rule adopted in 1902 in 318. A personal insight on the scene in the harbor just after the the 40-foot class chosen by P, CYC. A long bowsprit brought turn of the century was obtained fi’om Past Commodore John the Canadian boat, to be named Stralh{’oIla, to 61 feet long. Van Voorhis. Van Voorhis’ father would take him to dinner at theRYC had mustered a syndicate consisting of Hiram W. Sibley, West Side Clubhouse and they would look out on the river fiom James S. Watson, Thomas N. Finucane, Arthur G. Yates. John the porch and his father told him: N. Beckley, Albert O. Fenn, Walter B. Duffy, and Charles M. Everest. The group settled on a design by William Gardner, to Twenty to 30 sailboats were moored, mostly on be built at the Wood Boatyard in City Island, N.Y. The the east side of lhe river belween lhe Naval Iromh, quoil measured 65 feet overall. 40 t~et on the waterline, and had a beam of 12.5 feet with a draft of 0 feet. -

201504 Nauticallibrary V 1 7.Xlsx

Categories Title Author Subject Location P BIOGRAPHY AND 2.0000 AUTOBIOGRAPHY All This and Sailing Too Stephens ll, Olin J. Autobiography Olin Stephens 2.0001 Beken file, The (aka Beken, Ma Vie) Beken, Keith Selection of anecdotes & photos from Beken’s seagoing memories 2.0002 Wanderer Hayden, Sterling Autobio of Hollywood actor Hayden’s long affair with sailing offshore 2.0003 Admiral of the Ocean Sea Morison, Samuel Eliot Life of Christopher Columbus 2.0004 Conqueror of the Seas Zweig, Stefan Story of Ferdinand Magellan 2.0005 Nelson. Oman, Carola Detailed story of Nelson with much on his Royal Navy sea battles for Great Britain 2.0006 Nelson, Horatio Nelson Viscount 1758-1805 Remember Nelson : The Life of Captain Sir Pocock, Tom Story of Nelson protege, Capt Sir William Hoste 2.0007 William Hoste Two Barneys, The Hacking, Norman Story of RVYC members Captains Bernard L Johnson & son Bernard L Johnson 2.0008 and Johnson Walton Steamships history. Johnson, Bernard Leitch, 1878-1968 Johnson, 0 Bernard Dodds Leitch, 1904-1977 Merchant marine Portrait of Lord Nelson, A Warner, Oliver Capt Horatio Nelson, Viscount, 1758-1805 2.0009 Capt. Joshua Slocum Slocum, Victor Biographical account of the life and adventures of Joshua Slocum, as told by his 2.0010 son Victor Pull Together! Bayly, Admiral Sir Lewis Memoirs of Admiral Sir Lewis Bayley 2.0011 My Ninety Four Years on Planet Earth Summerfield, Roy H. Autobiography of Roy H. Summerfield, past RVYC member 2.0012 Sailing Alone Around the World and Voyage Slocum, Joshua Slocum’s account of his solo circumnavigation and subsequent voyage from Brazil 2.0013 of the Liberdade with wife & children on Liberdade Sailing: A Course of My Life Heath, Edward Heath autobiography centered on his lifetime of racing - featuring yacht Morning 2.0014 Cloud Sailing Boats Fox, Uffa Autobiography of Uffa Fox: his sailing life, designer and competitor 2.0015 Don’t Leave Any Holidays McCurdy, H. -

Seacare Authority Exemption

EXEMPTION 1—SCHEDULE 1 Official IMO Year of Ship Name Length Type Number Number Completion 1 GIANT LEAP 861091 13.30 2013 Yacht 1209 856291 35.11 1996 Barge 2 DREAM 860926 11.97 2007 Catamaran 2 ITCHY FEET 862427 12.58 2019 Catamaran 2 LITTLE MISSES 862893 11.55 2000 857725 30.75 1988 Passenger vessel 2001 852712 8702783 30.45 1986 Ferry 2ABREAST 859329 10.00 1990 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2GETHER II 859399 13.10 2008 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2-KAN 853537 16.10 1989 Launch 2ND HOME 856480 10.90 1996 Launch 2XS 859949 14.25 2002 Catamaran 34 SOUTH 857212 24.33 2002 Fishing 35 TONNER 861075 9714135 32.50 2014 Barge 38 SOUTH 861432 11.55 1999 Catamaran 55 NORD 860974 14.24 1990 Pleasure craft 79 199188 9.54 1935 Yacht 82 YACHT 860131 26.00 2004 Motor Yacht 83 862656 52.50 1999 Work Boat 84 862655 52.50 2000 Work Boat A BIT OF ATTITUDE 859982 16.20 2010 Yacht A COCONUT 862582 13.10 1988 Yacht A L ROBB 859526 23.95 2010 Ferry A MORNING SONG 862292 13.09 2003 Pleasure craft A P RECOVERY 857439 51.50 1977 Crane/derrick barge A QUOLL 856542 11.00 1998 Yacht A ROOM WITH A VIEW 855032 16.02 1994 Pleasure A SOJOURN 861968 15.32 2008 Pleasure craft A VOS SANTE 858856 13.00 2003 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht A Y BALAMARA 343939 9.91 1969 Yacht A.L.S.T. JAMAEKA PEARL 854831 15.24 1972 Yacht A.M.S. 1808 862294 54.86 2018 Barge A.M.S. -

Introduction to Risk Assessments for Methods Used in Wildlife Damage Management

Human Health and Ecological Risk Assessment for the Use of Wildlife Damage Management Methods by USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services Chapter I Introduction to Risk Assessments for Methods Used in Wildlife Damage Management MAY 2017 Introduction to Risk Assessments for Methods Used in Wildlife Damage Management EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services (WS) Program completed Risk Assessments for methods used in wildlife damage management in 1992 (USDA 1997). While those Risk Assessments are still valid, for the most part, the WS Program has expanded programs into different areas of wildlife management and wildlife damage management (WDM) such as work on airports, with feral swine and management of other invasive species, disease surveillance and control. Inherently, these programs have expanded the methods being used. Additionally, research has improved the effectiveness and selectiveness of methods being used and made new tools available. Thus, new methods and strategies will be analyzed in these risk assessments to cover the latest methods being used. The risk assements are being completed in Chapters and will be made available on a website, which can be regularly updated. Similar methods are combined into single risk assessments for efficiency; for example Chapter IV contains all foothold traps being used including standard foothold traps, pole traps, and foot cuffs. The Introduction to Risk Assessments is Chapter I and was completed to give an overall summary of the national WS Program. The methods being used and risks to target and nontarget species, people, pets, and the environment, and the issue of humanenss are discussed in this Chapter. From FY11 to FY15, WS had work tasks associated with 53 different methods being used. -

![MECHANIC , CIIEMIST]T 1 A.ND MANUFACTURES](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7493/mechanic-ciiemist-t-1-a-nd-manufactures-497493.webp)

MECHANIC , CIIEMIST]T 1 A.ND MANUFACTURES

/tWEEKLY JOURNA� PRACTIC L INFORMATION, ART, SCIENCE, MECHANIC�, CIIEMIST]t 1 A.ND OF. A � � MANUFACTURES. Vol. LIII.--No. 11. ] [$3.20 per AnnuDl.. [NEW SERlE'.] NEW YORK, SEPTEMBER 12, 1885. [POSTAGE PREPAID.] THE INTERNATIONAL YACHT RACE. quickly concluded that there was no centerboard sloop The great differences in width and draught of the Probably no former event in the history of yacht in this country of sufficient length to match against the two yachts at once mark the broad .distinction be racing has attracted so much attention as the trial Genesta, whereupon the flag officers of the New York tween the two classes of vessels, the Genesta being for the champiollship between British and American Club ordered such a one built, and about the same of the cutter, or "knife-blade," style, while center yachts in the vicinity of .New York during the week time some members of the Eastern Yacht Club also board sloops like the Puritan are sometimes styled 7. for the con- ordered another, both being centerboard sloops. Of in yachting vernacular" skimming dishes." commencing Sept. The arrangements . test were not made without a great deal of corre- these two yachts, the Puritan, of the Eastern Yacht The particulars of the Genesta's spars are given as spondence, extending through lllany months. The Club, was selected to sail against the Genesta. follows: Mast from deck to hounds, 52 feet; topmast race was for the possebsion of the prize cup won by the I The Puritan is of wood, and was built at South from fid to sheave, 47 feet; extreme boom, 70 feet; gaff, yacht America, in a contest with a fleet of British Boston. -

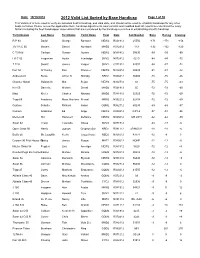

2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap Page 1 of 30 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Design Last Name First Name Yacht Name Fleet Date Sail Number Base Racing Cruising R P 90 David George Rambler NEW2 R021912 25556 -171 -171 -156 J/V I R C 66 Meyers Daniel Numbers MHD2 R012912 119 -132 -132 -120 C T M 66 Carlson Gustav Aurora NEW2 N081412 50095 -99 -99 -90 I R C 52 Fragomen Austin Interlodge SMV2 N072412 5210 -84 -84 -72 T P 52 Swartz James Vesper SMV2 C071912 52007 -84 -87 -72 Farr 50 O' Hanley Ron Privateer NEW2 N072412 50009 -81 -81 -72 Andrews 68 Burke Arthur D Shindig NBD2 R060412 55655 -75 -75 -66 Chantier Naval Goldsmith Mat Sejaa NEW2 N042712 03 -75 -75 -63 Ker 55 Damelio Michael Denali MHD2 R031912 55 -72 -72 -60 Maxi Kiefer Charles Nirvana MHD2 R041812 32323 -72 -72 -60 Tripp 65 Academy Mass Maritime Prevail MRN2 N032212 62408 -72 -72 -60 Custom Schotte Richard Isobel GOM2 R062712 60295 -69 -69 -57 Custom Anderson Ed Angel NEW2 R020312 CAY-2 -57 -51 -36 Merlen 49 Hill Hammett Defiance NEW2 N020812 IVB 4915 -42 -42 -30 Swan 62 Tharp Twanette Glisse SMV2 N071912 -24 -18 -6 Open Class 50 Harris Joseph Gryphon Soloz NBD2 -

Journal of the of Association Yachting Historians

Journal of the Association of Yachting Historians www.yachtinghistorians.org 2019-2020 The Jeremy Lines Access to research sources At our last AGM, one of our members asked Half-Model Collection how can our Association help members find sources of yachting history publications, archives and records? Such assistance should be a key service to our members and therefore we are instigating access through a special link on the AYH website. Many of us will have started research in yacht club records and club libraries, which are often haphazard and incomplete. We have now started the process of listing significant yachting research resources with their locations, distinctive features, and comments on how accessible they are, and we invite our members to tell us about their Half-model of Peggy Bawn, G.L. Watson’s 1894 “fast cruiser”. experiences of using these resources. Some of the Model built by David Spy of Tayinloan, Argyllshire sources described, of course, are historic and often not actively acquiring new material, but the Bartlett Over many years our friend and AYH Committee Library (Falmouth) and the Classic Boat Museum Member the late Jeremy Lines assiduously recorded (Cowes) are frequently adding to their specific yachting history collections. half-models of yachts and collected these in a database. Such models, often seen screwed to yacht clubhouse This list makes no claim to be comprehensive, and we have taken a decision not to include major walls, may be only quaint decoration to present-day national libraries, such as British, Scottish, Welsh, members of our Association, but these carefully crafted Trinity College (Dublin), Bodleian (Oxford), models are primary historical artefacts. -

DEPARTMENT of the TREASURY 31 CFR Part 33 RIN 1505-AC72 DEPARTMENT of HEALTH and HUMAN SERVICES 45 CFR Parts 155 and 156 [CMS-99

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 01/19/2021 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2021-01175, and on govinfo.gov[Billing Code: 4120-01-P] DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY 31 CFR Part 33 RIN 1505-AC72 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES 45 CFR Parts 155 and 156 [CMS-9914-F] RIN 0938-AU18 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; HHS Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for 2022; Updates to State Innovation Waiver (Section 1332 Waiver) Implementing Regulations AGENCY: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Department of Health & Human Services (HHS), Department of the Treasury. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: This final rule sets forth provisions related to user fees for federally-facilitated Exchanges and State-based Exchanges on the Federal Platform. It includes changes related to acceptance of payments by issuers of individual market Qualified Health Plans and clarifies the regulation imposing network adequacy standards with regard to Qualified Health Plans that do not use provider networks. It also adds a new direct enrollment option for federally-facilitated Exchanges and State Exchanges and implements changes related to section 1332 State Innovation Waivers. DATES: These regulations are effective on March 15, 2021. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Jeff Wu, (301) 492-4305, Rogelyn McLean, (301) 492-4229, Usree Bandyopadhyay, (410) 786-6650, Grace Bristol, (410) 786-8437, or Kiahana Brooks, (301) 492-5229, for general information. Aaron Franz, (410) 786-8027, for matters related to user fees. Robert Yates, (301) 492-5151, for matters related to the direct enrollment option for federally-facilitated Exchange states, State-based Exchanges on the Federal Platform, and State Exchanges.