The Teaching of German in Cincinnati: an Historical Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools

RESEARCH REPORT NOVEMBER 2014 Looking Forward to High School and College Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools Elaine M. Allensworth, Julia A. Gwynne, Paul Moore, and Marisa de la Torre TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Executive Summary Chapter 5 55 Who Is at Risk of Earning Less 7 Introduction Than As or Bs in High School? Chapter 1 Chapter 6 17 Issues in Developing and Indicators of Whether Students Evaluating Indicators 63 Will Meet Test Benchmarks Chapter 2 Chapter 7 23 Changes in Academic Performance Who Is at Risk of Not Reaching from Eighth to Ninth Grade 75 the PLAN and ACT Benchmarks? Chapter 3 Chapter 8 29 Middle Grade Indicators of How Grades, Attendance, and High School Course Performance 81 Test Scores Change Chapter 4 Chapter 9 47 Who Is at Risk of Being Off-Track Interpretive Summary at the End of Ninth Grade? 93 99 References 104 Appendices A-E ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the many people who contributed to this work. We thank Robert Balfanz and Julian Betts for providing us with very thoughtful review and feedback which were used to revise this report. We also thank Mary Ann Pitcher and Sarah Duncan, at the Network for College Success, and members of our Steering Committee, especially Karen Lewis, for their valuable feedback. Our colleagues at UChicago CCSR and UChicago UEI, including Shayne Evans, David Johnson, Thomas Kelley-Kemple, and Jenny Nagaoka, were instrumental in helping us think about the ways in which this research would be most useful to practitioners and policy makers. -

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

The Official Visitors Guide for the Chicago Northwest Region

CHICAGO NORTHWEST Visitors Guide Welcome to the Middle Ages Chicago Northwest’s Best In Glass Horse Racing’s Most Beautiful Track GIVE YOURSELF AN EDGE ARLINGTON HEIGHTS // ELK GROVE VILLAGE // ITASCA // ROLLING MEADOWS // ROSELLE // SCHAUMBURG // STREAMWOOD // WOOD DALE CHICAGONORTHWEST.COM CHICAGONORTHWEST.COM // 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EVENTS 4 GIVE YOURSELF AN EDGE GETTING AROUND INSERT WELCOME TO THE MIDDLE AGES 6 THINGS TO DO INSERT We would love to assist you. Stop by and say hello at our Visitor Center: HORSE RACING’S MOST BEAUTIFUL TRACK 8 DINING INSERT Meet Chicago Northwest Visitor Center A GRILLING DINING EXPERIENCE 10 1933 N. Meacham Rd., Suite 210 HOTELS INSERT Schaumburg, IL 60173 COMMUNITIES 11 (847) 490-1010 MAP CENTERFOLD Monday–Friday 9 a.m.–5 p.m. A TASTE OF JAPAN CLOSE TO HOME 15 ChicagoNorthwest.com CHICAGO NORTHWEST’S BEST IN GLASS 16 EXPLORE. ENGAGE. EDUCATE. 18 STREET EATS 20 STAFF CHICAGO NORTHWEST-STYLE PIZZA 22 Dave Parulo Welcome to Chicago Northwest, located on the President edge of Chicago and O’Hare International Airport. STEAKS, BURGERS, Heather Larson, CMP Director of Sales Indulge in everything our region has to offer, SEAFOOD AND MORE including sophisticated and affordable shopping Melinda Garritano, CSEE and dining, fantastic modern accommodations Senior Account Executive and family-friendly attractions. Carlos Madinya It’s simple to enjoy Chicago Northwest with our Account Executive Hello. ease of highway access, direct Metra trains to EXPERTLY Jennifer Needham Chicago and free parking everywhere! Account Executive Be part of the Chicago Northwest experience by visiting Christina Nied our interactive site ChicagoNorthwest.com from any of Partnership Manager GRILLED OVER your devices. -

Ziegler Genealogy

ZIEGLER GENEALOGY Nicl1olas -- -- Michael -- -- Peter Family Tree Compiled By JOHN A. M. ZIEGLER, Ph. D .. D. D. fvlinister - Author - Writer Sponsored By The PETER ZIEGLER ASSOCIATION PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR Glenn Printing Company Huntin~ton Park California Introduction For a number of years, my ambition has been to trace n1y ancestors to the one who came from Ger many. I knew it must have been in the Early Colon ial period. When publishing "Father and Son," a life-sketch of my father, Rev. Dr. Henry Ziegler, and of myself, I could not say that my father descended from a certain Ziegler ,vho came across at a definite time. This, therefore, was my problem. Collecting material for our Family Tree began. in a leisurely manner, more than thirty years ago. The Author The serious effort, however, was started about two years ago. Plans were completed the past summer for an extended visit to Pennsylvania, in order to form the acquaintance of our numerous relatives. and to visit the places where great grandfather, Peter Ziegler, and my father lived. A Ziegler family reunion was held in Hasson Park, Oil City, Pennsyl vania, August 26, 1933, with more than two hundred present. A Peter Ziegler Association was effected, Captain Harley Jacob Ziegler of Franklin being elected President: E. Willard Ziegler of Oil City, Vice President: Miss Nora Bell Ziegler of Oil City, Secretary-Treasurer. The Association unanimously ·; agreed to have the "Tree" published, the writer being the compiler. Subsequently, I visited Center, Clinton, Huntingdon, Blair, Snyder, Perry, York and Lebanon counties, Pennsylvania, also Baltimore, Maryland, From the York. -

UAB-Psychiatry-Fall-081.Pdf

Fall 2008 Also Inside: Surviving Suicide Loss The Causes and Prevention of Suicide New Geriatric Psychiatry Fellowship Teaching and Learning Psychotherapy MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Message Jamesfrom H .the Meador-Woodruff, Chairman M.D. elcome to the Fall 2008 issue of UAB Psychia- try. In this issue, we showcase some of our many departmental activities focused on patients of Wevery age, and highlight just a few of the people that sup- port them. Child and adolescent psychiatry is one of our departmental jewels, and is undergoing significant expansion. I am par- ticularly delighted to feature Dr. LaTamia White-Green in this issue, both as a mother of a child with an autism- spectrum disorder (and I thank Teddy and his grandmother both for agreeing to pose for our cover!), but also the new leader of the Civitan-Sparks Clinics. These Clinics are one of UAB’s most important venues for the assessment of children with developmental disorders, training caregivers that serve these patients, and pursuing important research outcome of many psychiatric conditions. One of our junior questions. The Sparks Clinics moved into the Department faculty members, Dr. Monsheel Sodhi, has been funded by of Psychiatry over the past few months, and I am delighted this foundation for her groundbreaking work to find ge- that we have Dr. White-Green to lead our efforts to fur- netic predictors of suicide risk. I am particularly happy to ther strengthen this important group of Clinics. As you introduce Karen Saunders, who shares how her own family will read, we are launching a new capital campaign to raise has been touched by suicide. -

Municipal Reference Library US-04-09 Vertical Files

City of Cincinnati Municipal Reference Library US-04-09 Vertical Files File Cabinet 1 Drawer 1 1. A3MC Proposed Merger Cincinnati Enquirer and Post 1977 and 1978 2. No Folder Name 3. A33 Cincinnati Post 4. A33 Cincinnati Enquirer 5. A33 Sale of the Enquirer 6. A33 Cincinnati Kurier 7. A33 Newspapers and Magazines 8. Navy 9. A34 Copying, Processes, Printing, Mimeographing, Microfilming 10. A34C Carts, Codes Cincinnati 11. A45Mc General Public Reports (Cincinnati City Bulletin Progress) 12. A49Mc Name- Cincinnati’s “Cincinnati and Queen City of the West 2” 13. Cincinnati- Nourished and Protected by the River that Gave It by William H. Hessler 14. Cincinnati-Name-Flower-Flag-Seal-Key-Songs 15. A49so Ohio 16. Last Edition Printed by the Cincinnati Time-Star July 19, 1958 17. Ohio Sesquicentennial Celebration 18. A6 O/Ohio History-Historical Societies 19. A6mc General Information (I) Cincinnati 20. General Information 2 Cincinnati 21. Cincinnati Geological Society 22. Cincinnati’s Birthdays 23. Pictures of Old Cincinnati 24. A6mc Historical Society- Cincinnati 25. A6mc Famous Cincinnati Families (Enquirer Series 1980) 26. A6mc President Reagan’s Visit to Cincinnati 12/11/81 27. A6mc Pres. Fords Visit to Cincinnati July 1975 and October 28, 1976 28. A6c Famous People Who have Visited Cincinnati 29. A Brief Sketch of the History of Cincinnati, Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce 30. Cincinnati History 31. History of Cincinnati 1950? 32. Cincinnati 1924 33. Cincinnati 1926 34. Cincinnati 1928 35. Cincinnati 1930 36. Cincinnati 1931 37. Cincinnati 1931 38. Cincinnati 1932 39. Cincinnati 1932 40. Cincinnati 1933 41. Cincinnati 1935 42. -

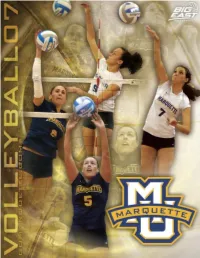

200708 Mu Vb Guide.Pdf

1 Ashlee 2 Leslie 4 Terri 5 Katie OH Fisher OH Bielski L Angst S Weidner 6 Jenn 7 Tiffany 8 Jessica 9 Kimberley 10 Katie MH Brown MH/OH Helmbrecht DS Kieser MH/OH Todd OH Vancura 11 Rabbecka 12 Julie 14 Hailey 15 Caryn OH Gonyo OH Richards DS Viola S Mastandrea Head Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach Pati Rolf Erica Heisser Raftyn Birath 20072007 MARQUETTE MARQUETTE VOLLEYBALL VOLLEYBALL TEAM TEAM Back row (L to R): Graydon Larson-Rolf (Manager), Erica Heisser (Assistant Coach), Kent Larson (Volunteer Assistant), Kimberley Todd. Third row: Raftyn Birath (Assistant Coach), Tiffany Helmbrecht, Rabbecka Gonyo, Katie Vancura, Jenn Brown, Peter Thomas (Manager), David Hartman (Manager). Second row: Pati Rolf (Head Coach), Ashlee Fisher, Julie Richards, Terri Angst, Leslie Bielski. Front row: Ellie Rozumalski (Athletic Trainer), Jessica Kieser, Hailey Viola, Katie Weidner, Caryn Mastandrea. L E Y B V O L A L L Table of Contents Table of Contents Quick Facts 2007 Schedule 2 General Information 2007 Roster 3 School . .Marquette University Season Preview 4 Location . .Milwaukee, Wis. Head Coach Pati Rolf 8 Enrollment . .11,000 Nickname . .Golden Eagles Assistant Coach Erica Heisser 11 Colors ...............Blue (PMS 281) and Gold (PMS 123) Assistant Coach Raftyn Birath 12 Home Arena . .Al McGuire Center (4,000) Meet The Team 13 Conference . .BIG EAST 2006 Review 38 President . .Rev. Robert A. Wild, S.J. 2006 Results and Statistics 41 Interim Athletics Dir. .Steve Cottingham Sr.Woman Admin. .Sarah Bobert 2006 Seniors 44 2006 Match by Match 47 Coaching Staff 2006 BIG EAST Recap 56 Season Preview, page 4 Head Coach . -

THE PANAMA CANAL REVIEW June 7, 1957 ??-/- /A ;-^..:.;

cluded such official facilities as swimming There's Fun To Be Had pools, playgrounds, and gj-mnasiums, and such non-governmental facilities as clubs and other employee organizations "de- Right Here In The Zone voted to the recreational, cultural, and fraternal requirements" of the Canal Zone's people. They discussed the aims and prob- lems of the program with Civic C:oun- cil groups and the Councils, in turn, helped by listing what facilities were already available and recommending others which their townspeople wanted. When its members had completed the survey, the subcommittee submitted a detailed 10-page report, breaking recre- ational facilities and needs down into geographical areas. The present Canal Zone recreational program, they decided, represents at least as far as the physical plant is concerned a somewhat haphazard accumulation of facilities acquired over the past 40 years, t| and commented that the periods of ex- V--" pansion and constriction of several towns 7.) were reflected in their recreational facili- ties. This was particularly true of Balboa, Gamboa, and Gatun and, to a lesser de- gree, of Diablo Heights and Margarita. Some of the present facilities, this group Shipping took a back seat as Scout crews paddled their cayucos through the found, were still useful but almost obso- Canal last month. The two boats here are racing toward Pedro Miguel Locks. lescent. One of the major sub-headings of this group's report dealt with "parks and monuments" such as Fort San Lorenzo, Barro Colorado Island, Summit Experi- ment Garden, the Madden Road Forest Preserve, and Madden Dam and the lake behind it. -

Victoria Kelleher

VICTORIA KELLEHER MASTER TALENT AGENCY - Greg Scuderi - 818-928-5032 – [email protected] RCM TALENT & MANAGEMENT - Laureen Muller - 323-825-1628 - [email protected] SBV COMMERCIAL TALENT - Rachel Fink - 323 938 6000 - [email protected] Television ALEXA & KATIE Guest Star Katy Garretson CRAZY EX-GIRLFRIEND Guest Star Stuart McDonald LIBERTY CROSSING Co-star Todd Berger LACY IS FUN Guest Star JANE THE VIRGIN Guest Star Zetna Fuentes BONES Guest Star Arlene THE MENTALIST Guest Star Paul Kaufman NCIS: LOS ANGELES Guest Star Eric A. Pott THE NEWSROOM Recurring Various MARON Guest Star SUPER FUN NIGHT Guest Star MAJOR CRIMES Guest Star Rick Wallace SQUARESVILLE Guest Star BEN & KATE Guest Star Fred Goss NEWSROOM Recurring Greg Mottola DESPERATE HOUSEWIVES Guest Star THE MIDDLE Guest Star Lee Shallat Chemel BROTHERS AND SISTERS Recurring Various PARKS AND RECREATION Guest Star Ken Kwapis INVINCIBLE Co-star CRIMINAL MINDS Guest Star Gloria Muzio THE WAR AT HOME Guest Star Andy Cadiff ROCK ME BABY Guest Star John Fortenberry THE BERNIE MAC SHOW Guest Star Lee Shallat Chemel THAT’S LIFE Recurring Jerry Levine ANGEL Guest Star Bll Norton HOLLYWOOD OFF RAMP Guest Star Ron Oliver THE TROUBLE WITH NORMAL Co-star Lee Shallat Chemel 3RD ROCK FROM THE SUN Guest Star Terry Hughes ALLY MCBEAL Guest Star Mel Damski CHICAGO HOPE Co-star Mel Damski FRIENDS Guest Star Gary Halvorson BECKER Co-star Lee Shallat Chemel Film ROCK BARNES Featured Ben McMillan THE HERO IN 1B Featured J. Elvis Weinstein PER-VERSIONS Lead Michael Wohl FLOURISH Lead Kevin -

Arab-American Media Bringing News to a Diverse Community

November 28, 2012 Arab-American Media Bringing News to a Diverse Community FOR FURTHER INFORMATION: Tom Rosenstiel, Director Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism Amy Mitchell, Deputy Director, Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism (202) 419-3650 1615 L St, N.W., Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20036 www.journalism.org Arab-American Media: Bringing News to a Diverse Community Overview If it were just a matter of population growth, the story of the Arab-American media would be a simple tale of opportunity. Over the last decade, Arab Americans have become one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States. But the story of the media trying to serve that audience is more complicated than that: The Arab-American population across the United States is ethnically diverse. Arab-American media are being buffeted by the same technology and economic trends as the news media generally, as well as a more challenging advertising market. And, advancements in technology have brought new competition from Arab outlets located in the Middle East and North Africa. Overall, the current Arab-American news media are relatively young. Newspapers and news websites are currently the most prominent sector, with much of the coverage focused on community news and events. There is also coverage at the national level, though, and recently, the Arab uprisings have given rise to more international coverage of news from “back home.” A number of papers are seeing rising circulation. Some new publications have even launched. However, most papers are still struggling to recover financially from the economic recession of 2007 and at the same time keep up with the trends in digital technology and social media. -

America's Long Road to the Federal Republic of Germany (West) by Robert A

1945 to 1948: America's Long Road to the Federal Republic of Germany (West) By Robert A. Selig NOV MAY SEP Close 25 35 captures Help 3 Mar 01 - 28 Jun 09 2005 2006 2007 June/July 1998 1945 to 1948: America's Long Road to the Federal Republic of Germany (West) By Robert A. Selig The December 1948 report by General Lucius D. Clay, commanding officer in the American Zone of Occupation in Germany, to U.S. President Harry S. Truman was full of optimism. "I think in looking back on 1948 we can look back on it as a year of material progress, and I think we can take considerable satisfaction in the state of affairs." Clay thought that 1948 had "brought back a real hope for the future among the 40-odd million people" in the American and British zones. This progress and hope, however, had only been possible because by the winter of 1947/48, American policy vis-à-vis Germany had undergone a complete reversal since the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht (Armed Forces) in May 1945. With surrender came the time for retribution. In the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) Directive 1067 of April 1945, General Dwight D. Eisenhower was instructed to occupy Germany "not...for the purpose of liberation but as a defeated enemy nation." Allied occupation was to bring "home to the Germans that Germany's ruthless warfare and the fanatical Nazi resistance have destroyed the German economy and made chaos and suffering inevitable and that the Germans cannot escape responsibility for what they have brought upon themselves." In Potsdam in July, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, and Truman set their common goals—the four Ds—for Germany: democratization, denazification, demilitarization, and decartellization (the break-up of trusts and industrial conglomerates).