Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

Academic Expectations and Guide to Success at MSA Grade 10

Academic Expectations and Guide to Success at MSA Grade 10 Welcome to tenth grade at the Math and Science Academy! Please read the following academic information and sign the agreement. Math and Science Academy has accelerated curricula, small class sizes, and is a rigorous, college-prep school. Regardless of a child’s previous academic scores on tests or grades in school, ALL tenth grade students will be placed in the following classes: Tenth Grade Courses All tenth grade students are registered for the following courses: British World Literature Modern World History Chemistry or AP Chemistry (see information below) Spanish class (see information below) Math class (see information below) Electives – two periods of electives; a combination of year-long and/or semester classes (2 full year classes = two electives/two periods; four semester-long classes = two periods) MATH New students: All incoming tenth grade students will be given a math placement exam. The math placement exam will determine if the student will be placed in Integrated Math II, Integrated Math III, Integrated Pre-calculus, or Pre-calculus. Please see the math information included in this guide for tenth grade. There are other options available to advance and graduate from MSA if the student is beginning in Integrated Math II. MSA’s math courses are advanced compared to other schools. Returning students: Returning students will follow the math progression courses and be placed accordingly. For example, if a student successfully completed Integrated Math III, the next course the student will take is Pre-calculus. SPANISH New students: All incoming tenth grade students with previous Spanish experience will take a placement test to determine a starting level and follow the flow chart from there. -

History Curriculum

History Curriculum Humanities (Grade Nine) Humanities History 9 is a full-year required course comprising the history portion of the ninth grade humanities curriculum. Curriculum Goals: • Developing the skills of critical thinking, close reading, and analytical writing, and mastering the importance of additional skills like note-taking and organization. • Exploring a global variety of past cultures and events and examining the connections among those cultures and the present. • Making connections between our own experiences and those of people from the past. Themes and Content: Our focus is directed at a number of historical attempts to create an “ideal” society which balances the needs of the individual with the needs of the community. We will investigate Confucianism in China, Democracy in Athens, Republicanism in Rome, and the Christian theocracy of the late Roman Empire. In each case, we will examine not only the ideas and origins of these social experiments, but also how well they met the challenges of their times. In our study, we will explore essential questions such as: • What is the purpose of government? • What do people expect from their governments? • How do different governments balance the needs of society against individual ambition and the desire for self-fulfillment? • What role do ethical systems (like religions) play in government? • How do societies based on an ideal form adapt to practical problems and challenges? Textbook: A variety of primary and secondary sources is distributed in class or accessed online. No textbook. World History (Grade Ten) This year-long course is designed to explore the people, events and trends that have shaped modern world history, from approximately 1300 AD to the present. -

The Official Visitors Guide for the Chicago Northwest Region

CHICAGO NORTHWEST Visitors Guide Welcome to the Middle Ages Chicago Northwest’s Best In Glass Horse Racing’s Most Beautiful Track GIVE YOURSELF AN EDGE ARLINGTON HEIGHTS // ELK GROVE VILLAGE // ITASCA // ROLLING MEADOWS // ROSELLE // SCHAUMBURG // STREAMWOOD // WOOD DALE CHICAGONORTHWEST.COM CHICAGONORTHWEST.COM // 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EVENTS 4 GIVE YOURSELF AN EDGE GETTING AROUND INSERT WELCOME TO THE MIDDLE AGES 6 THINGS TO DO INSERT We would love to assist you. Stop by and say hello at our Visitor Center: HORSE RACING’S MOST BEAUTIFUL TRACK 8 DINING INSERT Meet Chicago Northwest Visitor Center A GRILLING DINING EXPERIENCE 10 1933 N. Meacham Rd., Suite 210 HOTELS INSERT Schaumburg, IL 60173 COMMUNITIES 11 (847) 490-1010 MAP CENTERFOLD Monday–Friday 9 a.m.–5 p.m. A TASTE OF JAPAN CLOSE TO HOME 15 ChicagoNorthwest.com CHICAGO NORTHWEST’S BEST IN GLASS 16 EXPLORE. ENGAGE. EDUCATE. 18 STREET EATS 20 STAFF CHICAGO NORTHWEST-STYLE PIZZA 22 Dave Parulo Welcome to Chicago Northwest, located on the President edge of Chicago and O’Hare International Airport. STEAKS, BURGERS, Heather Larson, CMP Director of Sales Indulge in everything our region has to offer, SEAFOOD AND MORE including sophisticated and affordable shopping Melinda Garritano, CSEE and dining, fantastic modern accommodations Senior Account Executive and family-friendly attractions. Carlos Madinya It’s simple to enjoy Chicago Northwest with our Account Executive Hello. ease of highway access, direct Metra trains to EXPERTLY Jennifer Needham Chicago and free parking everywhere! Account Executive Be part of the Chicago Northwest experience by visiting Christina Nied our interactive site ChicagoNorthwest.com from any of Partnership Manager GRILLED OVER your devices. -

PARENTS ATTEND PRESCHOOL ORIENTATION Child’S Teacher and Were Able and Skill Development

EYE ON EDUCATION A Publication of the Paramount Unified School District 15110 CALIFORNIA AVE., PARAMOUNT, CA 90723 • TEL: 562-602-6000 • FAX: 562-634-6029 SEPTEMBER 2008 Paramount High School Welcomes the Class of 2011 The event was assisted Ms. Talamantes mentions with the incorporation of that “the event allowed for various student leaders from students to not only connect various campus clubs and with other students, it allowed organizations. Eleventh-grade for them to feel a sense of be- student-leader Lizbet Ordaz longing to our school culture.” mentions that “the Pirate She further explained that Orientation showed the stu- it gave students an opportu- dents that we are here to sup- nity to team build within their Paramount High School students to the senior campus counselors. Students submit- port them through their high own grade level. When asked held it’s first annual Sophomore in a way that showcased our ted all necessary school forms school journey. The students how she felt about the Pirate Pirate Orientation on August Pirate Pride!” during the registration process, will know where to go when Orientation, incoming tenth 13th and 14th. Paramount High A total of 826 incoming committed to personal goals they need help or assistance.” grade student Adriana Herrera School Counselors Patty Ja- tenth-grade students actively during the Path to Graduation Lizbet further explains that mentioned that “it was fun; it cobo and Maria Talamantes participated in the event and session, and interacted in nu- the Sophomore Pirate Orien- was a good way for us to get coordinated the event as a kick- were involved in three main merous team-building exercises tation experience will help the to know one another and com- off in implementing systematic sessions. -

UAB-Psychiatry-Fall-081.Pdf

Fall 2008 Also Inside: Surviving Suicide Loss The Causes and Prevention of Suicide New Geriatric Psychiatry Fellowship Teaching and Learning Psychotherapy MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Message Jamesfrom H .the Meador-Woodruff, Chairman M.D. elcome to the Fall 2008 issue of UAB Psychia- try. In this issue, we showcase some of our many departmental activities focused on patients of Wevery age, and highlight just a few of the people that sup- port them. Child and adolescent psychiatry is one of our departmental jewels, and is undergoing significant expansion. I am par- ticularly delighted to feature Dr. LaTamia White-Green in this issue, both as a mother of a child with an autism- spectrum disorder (and I thank Teddy and his grandmother both for agreeing to pose for our cover!), but also the new leader of the Civitan-Sparks Clinics. These Clinics are one of UAB’s most important venues for the assessment of children with developmental disorders, training caregivers that serve these patients, and pursuing important research outcome of many psychiatric conditions. One of our junior questions. The Sparks Clinics moved into the Department faculty members, Dr. Monsheel Sodhi, has been funded by of Psychiatry over the past few months, and I am delighted this foundation for her groundbreaking work to find ge- that we have Dr. White-Green to lead our efforts to fur- netic predictors of suicide risk. I am particularly happy to ther strengthen this important group of Clinics. As you introduce Karen Saunders, who shares how her own family will read, we are launching a new capital campaign to raise has been touched by suicide. -

The Calhoun School

THE CALHOUN SCHOOL TABLE OF CONTENTS Important Information 3 ❏ Course Registration Process ❏ Independent Study ❏ Adding or Dropping Classes ❏ External Academic Work ❏ Accelerating Mathematics Coursework Academic Planning Advice 6 ❏ For All Upper Schoolers ❏ For Rising Ninth Graders ❏ For Rising Tenth Graders ❏ For Rising Eleventh Graders ❏ For Rising Twelfth Graders 2019-2020 US Course Offerings & Descriptions ❏ New Courses for 2019-2020 9 ❏ English 10 ❏ Social Studies 18 ❏ Mathematics 26 ❏ World Languages 32 ❏ Science 39 ❏ Computer & Information Science 45 ❏ Music 46 ❏ Theater Arts 51 ❏ Visual Arts 55 ❏ Community Service 62 ❏ Physical Education 63 ❏ Special Courses 64 Other Academic Policies 66 ❏ Language Waiver Criteria ❏ Incompletes ❏ Academic/Social Probation COVER ILLUSTRATION: Oliver Rauch, Calhoun Class of 2019 2 IMPORTANT INFORMATION COURSE REGISTRATION PROCESS Each year during Mod 5, there will be a ten-day registration period during which students in grades 9-11 will select courses for the following school year. The registration process will begin at a special Town Meeting, which will be devoted to the introduction of the online Course Catalogue (including a preview of new courses) and an overview of the course registration process. Following the Town Meeting, cluster advisers will share a Course Registration Packet with each of their advisees. The packet will include the student’s current academic transcript, a Transcript Audit Review Form, and a Course Selection Form. Although it is ultimately the student’s responsibility to complete his/her Course Selection Form, this process works best when students consult with teachers, cluster advisors, and parents/guardians to make informed decisions. It is advised that each student utilize the Transcript Review Audit Form to ensure that adequate progress is being made toward all Calhoun graduation requirements. -

Connecting Through Projects

Student Roundtable Digital Portfolios Home Connecting through projects Projects are everywhere at High Tech High, and a look around the school on any given day will find students of every subject actively making things, trying things out, making them better. Teachers are learning, too, as they work in collegial teams to develop and share curriculum and to assess how students have gained. — from High Tech High’s Annual Curriculum Yearbook (2002) High Tech High is a project-based school. It means that my school does big, exciting, yet complicating assignments that require a lot of research, software and Internet usage, and ideas. This school isn’t just little textbook assignments and worksheets... — Quan Ton, HTH student t High Tech High, interdisciplinary study, links to the real world, and teamwork Ainvigorate teaching and learning at every step. And it is through projects that these three strands most often connect. Below we examine projects at HTH from the viewpoint of both faculty and students. The faculty commentaries, drawn from the school’s annual curriculum yearbook (which can be ordered through High Tech High Learning), reveal the multiple ways HTH teachers reach across disciplines and make learning relevant. The student project descriptions are but a small sample of the hundreds of summaries posted in the digital portfolios kept by each student. The examples we share here reflect the extraordinary range of projects that students pursue. As one student said simply, “I never would have thought to do a project like that!” Teacher interviews Student project descriptions Real world research “In science there’s a view that you have to have a Ph.D. -

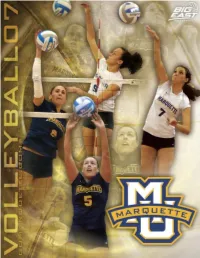

200708 Mu Vb Guide.Pdf

1 Ashlee 2 Leslie 4 Terri 5 Katie OH Fisher OH Bielski L Angst S Weidner 6 Jenn 7 Tiffany 8 Jessica 9 Kimberley 10 Katie MH Brown MH/OH Helmbrecht DS Kieser MH/OH Todd OH Vancura 11 Rabbecka 12 Julie 14 Hailey 15 Caryn OH Gonyo OH Richards DS Viola S Mastandrea Head Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach Pati Rolf Erica Heisser Raftyn Birath 20072007 MARQUETTE MARQUETTE VOLLEYBALL VOLLEYBALL TEAM TEAM Back row (L to R): Graydon Larson-Rolf (Manager), Erica Heisser (Assistant Coach), Kent Larson (Volunteer Assistant), Kimberley Todd. Third row: Raftyn Birath (Assistant Coach), Tiffany Helmbrecht, Rabbecka Gonyo, Katie Vancura, Jenn Brown, Peter Thomas (Manager), David Hartman (Manager). Second row: Pati Rolf (Head Coach), Ashlee Fisher, Julie Richards, Terri Angst, Leslie Bielski. Front row: Ellie Rozumalski (Athletic Trainer), Jessica Kieser, Hailey Viola, Katie Weidner, Caryn Mastandrea. L E Y B V O L A L L Table of Contents Table of Contents Quick Facts 2007 Schedule 2 General Information 2007 Roster 3 School . .Marquette University Season Preview 4 Location . .Milwaukee, Wis. Head Coach Pati Rolf 8 Enrollment . .11,000 Nickname . .Golden Eagles Assistant Coach Erica Heisser 11 Colors ...............Blue (PMS 281) and Gold (PMS 123) Assistant Coach Raftyn Birath 12 Home Arena . .Al McGuire Center (4,000) Meet The Team 13 Conference . .BIG EAST 2006 Review 38 President . .Rev. Robert A. Wild, S.J. 2006 Results and Statistics 41 Interim Athletics Dir. .Steve Cottingham Sr.Woman Admin. .Sarah Bobert 2006 Seniors 44 2006 Match by Match 47 Coaching Staff 2006 BIG EAST Recap 56 Season Preview, page 4 Head Coach . -

Greece--Selected Problems

REPORT RESUMES ED 013 992 24 AA 000 260 GREECE -- SELECTED PROBLEMS. BY- MARTONFFY, ANDREA PONTECORVO AND OTHERS CHICAGO UNIV., ILL. REPORT NUMBER BR-62445...1 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.50HC-$4.60 113F. DESCRIPTORS- *CURRICULUM GUIDES, *GREEK CIVILIZATION, *CULTURE, CULTURAL INTERRELATIONSHIPS,*PROBLEM SETS, *SOCIAL STUDIES, ANCIENT HISTORY, HIGH SCHOOL CURRICULUM A CURRICULUM GUIDE IS PRESENTED FOR A 10-WEEK STUDYOF ANCIENT GREEK CIVILIZATION AT THE 10TH -GRADE LEVEL.TEACHING MATERIALS FOR THE UNIT INCLUDE (1) PRIMARY ANDSECONDARY SOURCES DEALING WITH THE PERIOD FROM THE BRONZE AGETHROUGH THE HELLENISTIC PERIOD,(2) GEOGRAPHY PROBLEMS, AND (3) CULTURAL MODEL PROBLEM EXERCISES. THOSE CONCEPTSWITH WHICH THE STUDENT SHOULD GAIN MOST FAMILIARITY INCLUDETHE EXISTENCE OF THE UNIVERSAL CATEGORIES OF CULTURE(ECONOMICS, SOCIAL ORGANIZATION, POLITICAL ORGANIZATION,RELIGION, KNOWLEDGE, AND ARTS), THE INTERRELATEDNESS OF THESE CATEGORIES AT ANY GIVEN POINT IN TIME, AND THEINFLUENCE WHICH CHANGES IN ONE OF THESE MAY FLAY INPRECIPITATING LARGE -SCALE SOCIAL AND CULTURAL CHANGE. ANINTRODUCTION TO THE BIOLOGICAL DETERMINANTS (INDIVIDUAL GENETICCOMPOSITIONS) AND GEOGRAPHICAL DETERMINANTS (TOPOGRAPHY, CLIMATE,LOCATION, AND RESOURCES) OF GREEK CIVILIZATION IS PROVIDED.THE STUDENT IS ALSO INTRODUCED TO THE IDEA OF CULTURALDIFFUSION OR CULTURE BORROWING. (TC) .....Siiiir.i.......0.161,...4iliaalla.lilliW116,6".."`""_ GREECE:, SELEcT DPRO-BLES . Andrea POcorvoMartonffy& JOISApt, I. g ... EdgarBerwein, Geral Edi rs 4 CHICAGO SOCIALSTU i OJECT TRIAL EDITION Materials -

THE PANAMA CANAL REVIEW June 7, 1957 ??-/- /A ;-^..:.;

cluded such official facilities as swimming There's Fun To Be Had pools, playgrounds, and gj-mnasiums, and such non-governmental facilities as clubs and other employee organizations "de- Right Here In The Zone voted to the recreational, cultural, and fraternal requirements" of the Canal Zone's people. They discussed the aims and prob- lems of the program with Civic C:oun- cil groups and the Councils, in turn, helped by listing what facilities were already available and recommending others which their townspeople wanted. When its members had completed the survey, the subcommittee submitted a detailed 10-page report, breaking recre- ational facilities and needs down into geographical areas. The present Canal Zone recreational program, they decided, represents at least as far as the physical plant is concerned a somewhat haphazard accumulation of facilities acquired over the past 40 years, t| and commented that the periods of ex- V--" pansion and constriction of several towns 7.) were reflected in their recreational facili- ties. This was particularly true of Balboa, Gamboa, and Gatun and, to a lesser de- gree, of Diablo Heights and Margarita. Some of the present facilities, this group Shipping took a back seat as Scout crews paddled their cayucos through the found, were still useful but almost obso- Canal last month. The two boats here are racing toward Pedro Miguel Locks. lescent. One of the major sub-headings of this group's report dealt with "parks and monuments" such as Fort San Lorenzo, Barro Colorado Island, Summit Experi- ment Garden, the Madden Road Forest Preserve, and Madden Dam and the lake behind it.