Mesolithic and Early Neolithic Activity Along the Dee: Excavations at Garthdee Road, Aberdeen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aberdeen Access from the South Core Document

Aberdeen Access from the South Core Document Aberdeen City Council, Aberdeenshire Council, Nestrans Transport Report 69607 SIAS Limited May 2008 69607 TRANSPORT REPORT Description: Aberdeen Access from the South Core Document Author: Julie Sey/Peter Stewart 19 May 2008 SIAS Limited 13 Rose Terrace Perth PH1 5HA UK tel: 01738 621377 fax: 01738 632887 [email protected] www.sias.com i:\10_reporting\draft reports\core document.doc 69607 TRANSPORT REPORT CONTENTS : Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Study Aims 2 1.3 Report Format 2 2 ANALYSIS OF PRESENT AND FUTURE PROBLEMS 3 2.1 Introduction 3 2.2 Geographic Context 3 2.3 Social Context 4 2.4 Economic Context 5 2.5 Strategic Road Network 6 2.6 Local Road Network 7 2.7 Environment 9 2.8 Public Transport 10 2.9 Vehicular Access 13 2.10 Park & Ride Plans 13 2.11 Train Services 14 2.12 Travel Choices 15 2.13 Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (AWPR) 17 2.14 Aberdeen Access from the South Problems Summary 17 3 PLANNING OBJECTIVES 19 3.1 Introduction 19 3.2 Aims 19 3.3 Structure Plans & Local Plans 19 3.4 National Policy 22 3.5 Planning Objective Workshops 23 3.6 Planning Objectives 23 3.7 Checking Objectives are Relevant 25 4 OPTION GENERATION, SIFTING & DEVELOPMENT 27 4.1 Introduction 27 4.2 Option Generation Workshop 27 4.3 Option Sifting 27 4.4 Option and Package Development 28 4.5 Park & Ride 32 5 ABERDEEN SUB AREA MODEL (ASAM3B) ITERATION 33 5.1 Introduction 33 5.2 ASAM3b Development Growth 33 5.3 ASAM3B Influence 33 19 May 2008 69607 6 SHORT TERM OPTION ASSESSMENT 35 6.1 Introduction -

The Biology and Management of the River Dee

THEBIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OFTHE RIVERDEE INSTITUTEofTERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY NATURALENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL á Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY The biology and management of the River Dee Edited by DAVID JENKINS Banchory Research Station Hill of Brathens, Glassel BANCHORY Kincardineshire 2 Printed in Great Britain by The Lavenham Press Ltd, Lavenham, Suffolk NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATIONDATA The biology and management of the River Dee.—(ITE symposium, ISSN 0263-8614; no. 14) 1. Stream ecology—Scotland—Dee River 2. Dee, River (Grampian) I. Jenkins, D. (David), 1926– II. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ill. Series 574.526323'094124 OH141 ISBN 0 904282 88 0 COVER ILLUSTRATION River Dee west from Invercauld, with the high corries and plateau of 1196 m (3924 ft) Beinn a'Bhuird in the background marking the watershed boundary (Photograph N Picozzi) The centre pages illustrate part of Grampian Region showing the water shed of the River Dee. Acknowledgements All the papers were typed by Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs E J P Allen, ITE Banchory. Considerable help during the symposium was received from Dr N G Bayfield, Mr J W H Conroy and Mr A D Littlejohn. Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs J Jenkins helped with the organization of the symposium. Mrs J King checked all the references and Mrs P A Ward helped with the final editing and proof reading. The photographs were selected by Mr N Picozzi. The symposium was planned by a steering committee composed of Dr D Jenkins (ITE), Dr P S Maitland (ITE), Mr W M Shearer (DAES) and Mr J A Forster (NCC). -

A Directory for the City of Aberdeen

F 71 JljfjjUiLSJL J)....L3. v. 3 %. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/directoryforcity183536uns : DIRECTORY CITY OF ABERDEEN 1835-36. 1035$ ABERDEEN Printed by D. CHALMERS & CO. FOR GEO. CLARK & SON, T. SPARK, AND D. WYLLIE & SON. MDCCCXXXV. C?/^ ;£?£-.:£>/*. £p£r43 CONTENTS. Directory, -.,---" 5 Magistrates and Incorporations, - - 180 Alphabetical List of Streets, Squares, &c. - i Carriers, - - , <-. xiii Mail Coaches, ----- xx Stage Coaches, - xxi Shipping Companies, - - - - xxiv Steam Packets, ----- xxv Principal Fairs, - - - - xxvi Post Towns and Postmasters in Scotland, - xxxiii Bridewell Assessment ; Rogue Money ; and King's Subsidy, - - - - - xxxvi Abstract of Population, - ib. List of the Shore Porters, - xxxvii Fire Engine Establishment, - ib. different Parishes in Aberdeen and Old Machar, ----- xxxviii Assessed Tax Tables for Scotland, - - xli Table of Appointments, 1835-36, - - xlvii Stamp Duties, - - - - - xlviii Imperial Weights and Measures, - - xlxix Schedule of Fees, - 1 Weigh-house Dues, - li Petty Customs, - liii Corn Laws, ----- lvii > ABERDEEN DIRECTORY 1835-36. Abel, John., blacksmith, 1, College-lane Peter, coal-broker, 4, Commerce-street Christian, poultry-shop, 76, h. Sutherland's-court, 78, Shiprow Abercrombie, Alexander, merchant, 49, Guestrow Robert, merchant, 49, Guestrow Aberdeen Academy, 115, Union-street Advertiser Office, Lamond's-court, 49, Upperkirkgate Banking Co., 53, Castle-street Brewery, 77, Causewayend, Robert M'Naughton, brewer Brick and Tile Co., Clayhills— Office, 40, Union-street Carpet Warehouse, (Wholesale and Retail,) 1, Lower Dee-street Coach Manufacturing Co., 7, Frederick- street, and 101, King-st. Commercial, Mathematical, and Nautical School, 10, Drum's- lane—W. Elgen Eye and Ear Institution, 7, Littlejohn-st. -

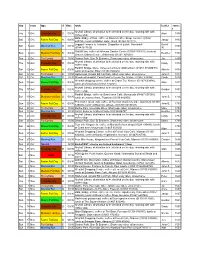

Day Mon Type D Time Route Leader Sunse T Thu 3 Oct

day mon type dtimeroute leadersunse t Airyhall Library, destination to be decided on the day, morning ride with Thu 3Oct Thursday Run D 09:30 Alan 1838 coffee stop. B&Q, Bridge of Don, coffee at Ross's Coffee Shop, Inverurie (01467 Sat 5Oct Faster Full Day A 09:00 Jacqui 1833 620764), lunch at Station Hotel, Insch (01464 821111). Leggart Terrace to Teacake, Chapelton of Elsick, Newtonhill David Sat 5Oct Morning Run D 09:30 1833 (07841917150) W. Old Mill Inn, coffee at Kirktown Garden Centre (01569 764343), lunch at Sun 6Oct Medium Full Day B 09:30 Heather 1830 Grassic Gibbon Centre, Arbuthnott (01561 361668) Sun 6 Oct Try Cycling E 10:00 Seaton Park, Don St Entrance, Short easy rides, all welcome. Joe 1830 Airyhall Library, destination to be decided on the day, morning ride with Thu 10Oct Thursday Run D 09:30 Cindy 1819 coffee stop. Parkhill Bridge, Dyce, coffee at Lochters, Oldmeldrum (01651 872000/78), Sat 12Oct Faster Full Day A 09:00 Alberto 1814 lunch at New Inn, Ellon (01358 720425). Sat 12 Oct Try Cycling E 10:00 Hazlehead, Groats Rd Car Park, Short easy rides, all welcome. John C. 1814 Sat 12 Oct Morning Run D 09:30 Woodend Hospital, Eday Road to Ceann Tor, Kintore (01467 633996) Cindy 1814 Westhill shopping centre, coffee at Ceann Tor, Kintore (01467 633996), Sun 13Oct Slower Full Day C 09:30 Alan 1811 lunch at Morris hotel (01651 872251) Airyhall Library, destination to be decided on the day, morning ride with Thu 17Oct Thursday Run D 09:30 Gordon 1801 coffee stop. -

Dictionary of Deeside Date Due Digitized by the Internet Archive

UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH LIBRARY 3 lift fl 010753m T VJ UNIV SOCSCI DA 8825. M C5B Coutts, James, 1B52- Dictionary of Deeside Date due Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/dictionaryofdeescout — IH Aberdeen University Press Book Printers •> •:• •:• •:• liaoi and Commercial Printers Stereo- and Electrotypers •:• Typefounders •:• •:• •:• •:• Have the largest assortment—over 400 Tons of the finest type in Scotland, in various langu- ages—Bengali, German, Greek, Hebrew, Russian, etc. ; also Music, in Old and New Notation and Gregorian. They have the finest Machinery of any Printer in the United Kingdom—without exception. This unique position places them in the front rank of British Printers. All Documents of a Private and Confidential nature have the personal care of the Comptroller. Having an extensive connection with the lead- ing Publishers, they are in a position to arrange for the publication of works of any kind. ESTIMATES FREE. & Telegrams: "PICA, ABERDEEN "• PREMIER CODE USED. CppvL-ij- hi JoLtl B artliolomew 3c Co „E imT Dictionary of Deeside A GUIDE TO THE CITY OF ABERDEEN AND THE VILLAGES, HAMLETS, DISTRICTS, CASTLES, MANSIONS AND SCENERY OF DEESIDE, WITH NOTES ON ANTIQUITIES, HISTORICAL AND LITERARY ASSOCIATIONS, ETC. BY l \ '/ JAMES COUTTS, M.A. WITH PLAN OF CITY, MAP OF COUNTRY AND TEN ILLUSTRATIONS " The Dee is a beautiful river —Byron ABERDEEN THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1899 1 lUl^f PREFACE. The spirit that prompted the question— " Are not Abana and Pharphar, rivers of Damascus, better " than all the waters of Israel ? —still survives. Sir Walter Scott has commented on the " reverence which . the Scotch usually pay to their dis- tinguished rivers. -

Route Descriptions

Route Descriptions Route Numbers reflect those marked on Core Paths Plan maps) The following descriptions of each proposed core path (CP) and longer term aspirational path (AP) are provided in order to give an indication of the type of path, why it has been designated as a core path or referred to as a longer term aspirational path, and any other relevant details. The route descriptions are not meant as route guides for people to use to navigate them. Where a suggestion is given on the suitability of routes for different user types and abilities (e.g. walkers, cyclists, horse riders, watersports, wheelchairs), this is for the purposes of giving an indication of the extent to which the Plan caters for the range of users that it is required to cater for. The outdoors must be enjoyed responsibly and the Scottish Outdoor Access Code should be referred to for further guidance. Route No. Route Description Route No. Route Description CP1 Blackburn to Kirkhill Forest CP63 Den of Cults (north) CP2 East of Coreshill to Kirkhill Forest CP64 Pinewood Park to Springfield Place CP3 Kirkhill Forest to Kirkhill Industrial Estate CP65 Hazlehead to River Dee Path CP4 Kirkhill to Bucksburn CP66 Deeside Way CP5 Formartine and Buchan Way CP67 Rocklands Road CP6 Dyce to Bridge of Don CP68 Den of Cults CP7 Persley Bridge to Grandholm Bridge (South Don) CP69 Duthie Park CP8 Auchmill Golf Course CP70 River Dee Path (north bank) CP9 Aberdeen Airport to Inverurie Road CP71 Dyce Airport Cycle Path CP10 Fairview Street to Fairview Brae CP72 North Deeside Road to River -

Interim Report

NELPD Local Flood Risk Management Plan 2016-2022: INTERIM REPORT Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act 2009: INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan North East Local Plan District 1 NELPD Local Flood Risk Management Plan 2016-2022: INTERIM REPORT Published by: Aberdeenshire Council In conjunction with; 2 NELPD Local Flood Risk Management Plan 2016-2022: INTERIM REPORT Publication date: 1 March 2019 Terms and conditions Ownership: All intellectual property rights INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan are owned by Aberdeenshire Council, SEPA or its licensors. The INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan cannot be used for or related to any commercial, business or other income generating purpose or activity, nor by value added resellers. You must not copy, assign, transfer, distribute, modify, create derived products or reverse engineer the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan in any way except where previously agreed with Aberdeenshire Council or SEPA. Your use of the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan must not be detrimental to Aberdeenshire Council or SEPA or other responsible authority, its activities or the environment. Warranties and Indemnities: All reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan is accurate for its intended purpose, no warranty is given by Aberdeenshire Council or SEPA in this regard. Whilst all reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan are up to date, complete and accurate at the time of publication, no guarantee is given in this regard and ultimate responsibility lies with you to validate any information given. -

Let's Get Straight to the Point

Let’s get straight to the point. Prime office pavilion High specification Offices from 3,000 to 18,000 sqft Generous on site parking Westpoint Six is located in Aberdeen is commonly known as the Energy - The £40 million Centre for Life Sciences Westpoint Business Park, Capital of Europe, being the major service base innovation project, which aims to double the for North Sea oil and gas exploration and number of life sciences companies present in Westhill. Westhill is widely production industries. The city has been subject the area over the next five years. of significant recent investment. recognised as a global centre Westhill is considered one of Aberdeen’s prime of excellence in the field of Recently completed projects include; out of town office locations. The area is home to a subsea engineering. - The £1Bn Aberdeen bypass (or AWPR) world class cluster of subsea companies and is - Aberdeen airport expansion known in the energy sector as “Surf City” – an - The £333m Exhibition and Conference abbreviation of subsea umbilicals, risers and Facility (TECA) flow lines, the main components in the subsea - Equinor’s £220m Hywind Development, the sector. Key occupiers at Westhill include Total, world’s first floating offshore windfarm. TechnipFMC, Schlumberger, Boskalis and Subsea 7. Projects due to complete shortly include; - £350m Aberdeen South Harbour expansion Westhill has recently been identified as the - The £70m investment into state-of-the-art preferred location for the UK Government’s digital infrastructure. Aberdeen remains on ‘Global Underwater Hub’, with over £6.3m track to become Britain’s first ‘Gigabit city’ of funding announced by the Chancellor of - The creation of the Oil and Gas Technology the Exchequer in the March 2021 Budget. -

A Directory for the City of Aberdeen

Dicjjjjzed by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/directoryforcity183839uns : I DIRECTORY DITY OF ABERDEEN • AND IXS^ICINITY. ISSS—39. ABERDEEN GEO. CLARK & SON, T. SPARK, AND D. WYLLIE & SON. 1838. ' : a/*f.fl7,»idl5-/5 ABERDEEN PRINTED AT THE CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICE, 42, CASTLE STREET, BY JOHN DAVIDSON. k 1 M CONTENTS. 5 Directory, - 185 Supplement to Directory, - Alphabetical List of Streets, Squares, &c. i xiii Carriers, ------ xix Principal Fairs, - xxiv Mail Coaches, - xxv Stage Coaches, -.*""" xxviix Shipping Companies, - Steam Packets, - xxix xxxi List of the diiferent Parishes in Aberdeen and Old Machar, Assessed Tax Tables for Scotland, Weigh-house Dues, - x/xvm Stamps and Taxes, -•--"." xl Commissioners of Police, - ib. Imperial Weights and Measures, xli Schedule of Fees, - xlii Aberdeen Assurance Fire Engine Establishment, xliii List of the Shore Porters, - ib. North of Scotland Assurance Fire Engine Establishment, xliv Abstract of Population, - - xlv Bridewell Assessment, Rogue Money, and King's Subsidy, ib. Corn Laws, ------ ib. Table of Duties on Grain, - xlvii Table of Appointments, 1838-39, xlix Stamp Duties, - 1 Grain Table, ------ li Magistrates and Incorporations, - lii ABERDEEN DIRECTORY, 1838—39. Abel, John, blacksmith, 1, College-lane Peter, coal-broker, 4, Commerce-street Christian, poultry-shop, 76, h. Sutherland's-court, 78, Shiprovv Mrs. 50, Virginia-street Aberdeen Academy, 115, Union-street, and 1, Ragg's-lane Apothecaries' Hall, 24, Union-street Banking Company, 53, Castle-street Brick & Tile Co's. Works, Clayhills—Office, 40, Union-street retail), Dee-street . Carpet Warehouse (wholesale & 1, Lower —— Coach Manufacturing Co. 7, Frederick-st. -

Aberdeen City Council BRIDGE of DEE WEST

Aberdeen City Council BRIDGE OF DEE WEST - ACTIVE TRAVEL CORRIDOR Options Appraisal Study - Executive Summary 7062153_EXECUTIVE SUMMARY JUNE 2020 PUBLIC Aberdeen City Council BRIDGE OF DEE WEST - ACTIVE TRAVEL CORRIDOR Options Appraisal Study - Executive Summary TYPE OF DOCUMENT (VERSION) PUBLIC PROJECT NO. 7062153 OUR REF. NO. 7062153_EXECUTIVE SUMMARY DATE: JUNE 2020 PUBLIC QUALITY CONTROL Issue/revision Issue 1 Remarks Executive Summary of Final Report Date 04/06/2020 Prepared by Chris Harris Signature Checked by Paul White Signature Authorised by Paul White Signature Project 7062153 number Report number FR_ES_001 File reference 7062153_RoI BRIDGE OF DEE WEST - ACTIVE TRAVEL CORRIDOR PUBLIC | WSP Project No.: 7062153 | Our Ref No.: 7062153_FR001 June 2020 Aberdeen City Council EXECUTIVE SUMMARY WSP UK Ltd. (WSP) has been commissioned by Aberdeen City Council (ACC) to undertake an active travel feasibility study for the Garthdee area of Aberdeen based on the principles set out in Transport Scotland’s Scottish Transport Appraisal Guidance (STAG). This Executive Summary presents an overview of the different phases of the study, together with the key findings and recommended next steps. The study area The study area was defined at the project inception by ACC and is shown in Figure ES-1 below. It centres on the Garthdee area, and also includes Kaimhill, Mannofield and Braeside. Figure ES-1 - Study Area Why is this study required? The construction of the Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (AWPR) has addressed some of Aberdeen’s transport challenges, including diverting strategic vehicular traffic away from the central city transport network. This change in transport conditions has allowed more focus on delivering the BRIDGE OF DEE WEST - ACTIVE TRAVEL CORRIDOR PUBLIC | WSP Project No.: 7062153 | Our Ref No.: 7062153_Executive Summary June 2020 Aberdeen City Council Page 1 actions set out by ACC within their Local Transport Strategy and Active Travel Action Plan. -

Milltimber Brae Report

Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route Alternative Routes STAG Part 1 Assessment Milltimber Brae Route Proposal Details Name and address of authority or organisation promoting the proposal: Scottish Executive Proposal Name Milltimber Brae Route Name of Planner AWPR Managing Agent Dual two lane carriageway Special Capital Cost £265m to £365m Road with grade separated Annual junctions forming a key Estimated Total Public Sector revenue - Proposal Description component of the Modern Funding Requirement support Transport System as identified in Present Value - the MTS STAG Part 1. of costs Scottish Executive (81%) £265m to £365m Funding sought from Aberdeen City Council (9.5%) Amount of Application (Predicted Out-turn Cost) Aberdeenshire Council (9.5%) Page 1 Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route Alternative Routes STAG Part 1 Assessment Milltimber Brae Route Background Information Aberdeen is the urban centre of North-East Scotland. The existing trunk road network runs through Aberdeen, with the local road network entering the city radially. The existing highway infrastructure in many areas is significantly constrained, with the trunk road bridge across the River Dee being unable to accommodate heavy goods vehicles and the trunk road through Aberdeen having a number of traffic signal controlled junctions and at grade roundabouts. In addition, over much of its length the trunk road is on a steep vertical alignment and is closely bounded by a mix of Geographic Context residential, leisure and commercial premises. These various constraints result in diversion by drivers onto local roads, causing further congestion across the network. The study area straddles the Aberdeenshire/Aberdeen City Council boundary and comprises primarily of Aberdeen’s rural hinterland although it passes close to or through several built up areas within the city boundaries. -

The Joint Meeting of the International Conference on Ephemeroptera and International Symposia on Plecoptera Takes Place Approximately Every Three Years

The Joint Meeting of the International Conference on Ephemeroptera and International Symposia on Plecoptera takes place approximately every three years. The 2012 meeting took place in Wakayama City, Japan. At this meeting it was agreed that the next Joint Meeting be held in Aberdeen, Scotland on the 31st May to 5 June 2015. A partnership formed between Buglife – The Invertebrate Conservation Trust, The Riverfly Partnership, The Riverfly Recording Schemes, Freshwater Biological Association, the James Hutton Institute and The Natural History Museum London, deliver the Joint Meeting of the XIV International Conference on Ephemeroptera and XVIII International Symposia on Plecoptera in Aberdeen, Scotland. VENUE Aberdeen, Scotland’s third largest city, is located on the stunning north east coast between the Rivers Don and Dee. The city has striking granite architecture, an inspiring history, strong industrial heritage, a vibrant population and a thriving art scene. The county of Aberdeenshire has stunning scenery, including Scotland’s largest national park – the Cairngorms National Park. The city has excellent facilities for the Joint Meeting with the Dee and Don catchments and surrounding habitats providing outstanding opportunities for fieldwork. North east Scotland supports a high proportion of the UK Ephemeroptera and Plecoptera fauna, including Brachyptera putata – an endemic species with government conservation status. All lectures and welcome/farewell receptions will be held in the Macaulay Suite at the James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen. Additional small meeting rooms will be available for quiet working or committee meetings. Free Wireless Internet access is available to all delegates at the conference venue. Username and password can be collected at the Registration desk upon arrival.